The Lost House Summary, Characters and Themes

The Lost House by Melissa Larsen is a psychological mystery that explores the fraught intersections of personal trauma, generational memory, and crime. Set against the stark and evocative Icelandic landscape, the novel follows two women—Ása, a troubled local university student spiraling into a fugue state, and Agnes, an American grappling with addiction and grief—whose lives intersect through a decades-old murder and a present-day disappearance.

The narrative alternates between their perspectives, gradually revealing how the past reverberates into the present. With themes of haunting—both literal and metaphorical—the novel raises questions about identity, inherited legacy, and the slippery nature of truth in the face of familial and societal mythologies.

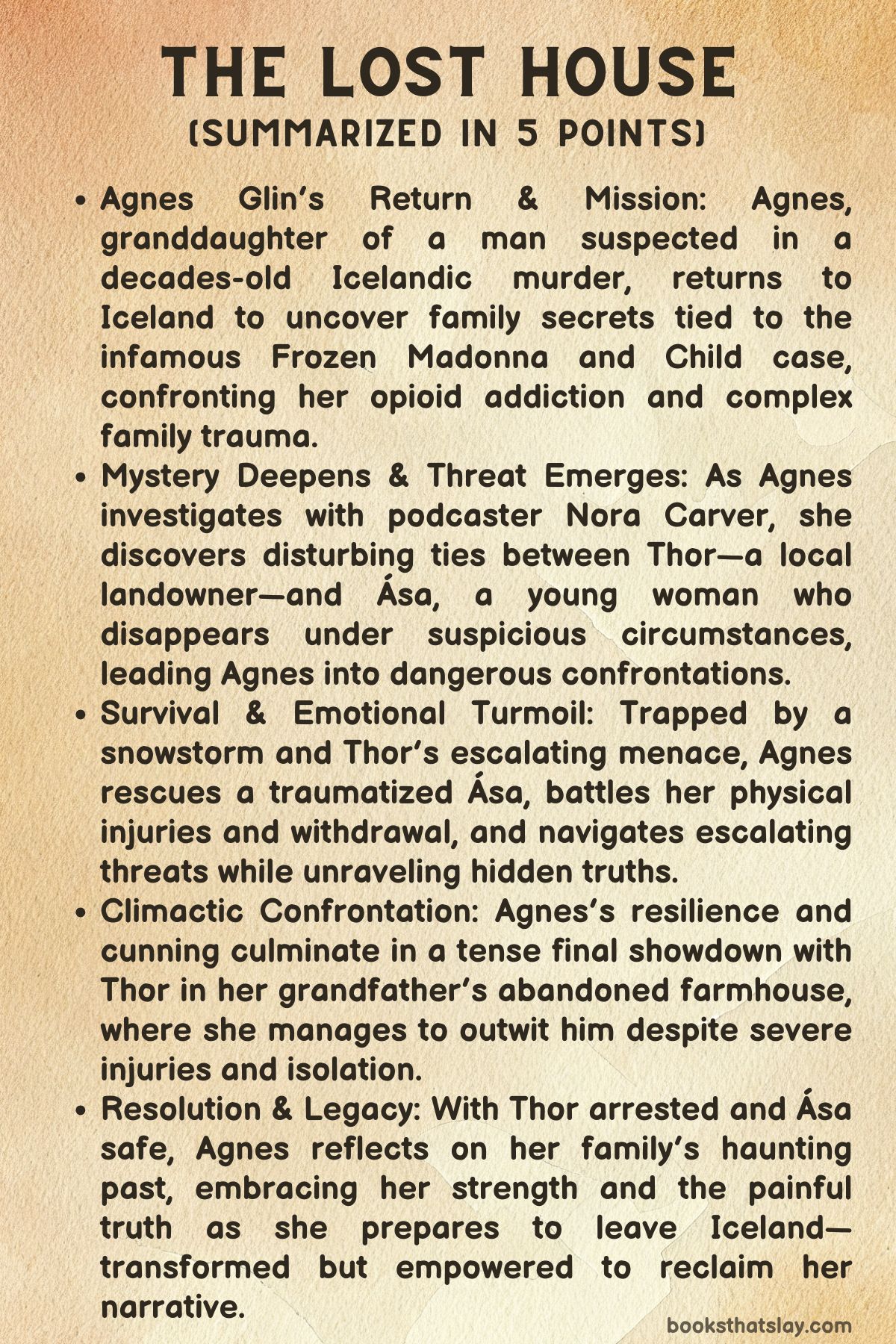

Summary

The story begins on a frigid February night in Iceland with Ása Gunnarsdóttir, a young woman in distress. At a wild party, overwhelmed by the weight of betrayal and emotional exhaustion, she contemplates sending a scathing text message: “I hope I haunt you.

” Her intoxication and psychological unraveling isolate her from those around her, including her friend Lilja and her partner Óskar, whose presence only magnifies her sense of alienation. Fleeing into the icy landscape, she wanders off alone, lost in both body and mind.

Her thoughts fragment into hallucinations and half-remembered sounds, until unseen hands lift her from the snow, leaving her fate ambiguous and terrifying.

Just two days later, another narrative begins as Agnes Glin arrives in Iceland from California. Still recovering from a traumatic surfing injury and grappling with opioid dependency, she has come to participate in a podcast project investigating the unsolved murder of her grandmother Marie Hvass and infant aunt, Agnes, who were found dead in the snow in 1979.

The murder became infamous as the case of “the Frozen Madonna and Child. ” Marie’s throat had been slashed and the baby was drowned and frozen.

Though her grandfather Einar Pálsson was widely suspected, he was never convicted. Agnes’s father, Magnús, has long controlled the family narrative, offering a sanitized version of events that leaves Agnes suspicious and estranged from him.

Her decision to join the podcast investigation causes deep tension between them, especially because he views it as a betrayal.

Agnes is hosted by Nora Carver, the magnetic and driven creator of The End, a true crime podcast that had previously helped resolve a cold case in California. Nora is intense, fanatical about her work, and uncomfortably fascinated by Agnes’s resemblance to her grandmother Marie.

She has gone so far as to rent a modern luxury home built on the very land that once belonged to Einar. Agnes is uneasy about this obsession, but she is also drawn to the opportunity to take ownership of her family’s story.

However, the deeper she gets into the case, the more she feels the emotional cost of reopening old wounds—especially as Nora presses her for participation in dramatized reenactments and audio reconstructions for the show.

Meanwhile, the recent disappearance of Ása Gunnarsdóttir becomes a parallel mystery. A photograph of her, pinned up in a café in Reykjavík, bears a shocking resemblance to both Marie and Agnes.

Nora immediately believes there’s a connection between Ása’s vanishing and the 1979 murders. The revelation pushes the investigation from retrospective into present-day danger.

Suddenly, Agnes is not merely a descendant seeking closure, but a potential target or key to unraveling a repeating cycle.

The novel grows increasingly tense as Agnes and Nora navigate the uncomfortable balance between sensationalism and truth-seeking. Agnes, who had previously avoided listening to the podcast’s coverage of her family’s case, now faces the trauma in full force.

She is haunted not only by the violent images of her grandmother and baby aunt frozen in death, but also by the memories of her own childhood, her strained relationship with her father, and her battle with addiction. She struggles with guilt, not just over her reliance on painkillers, but over what she perceives as failures in loyalty, memory, and even personhood.

As they dig further into both the cold case and Ása’s disappearance, the narrative blurs lines between past and present, obsession and investigation, storytelling and truth. Nora becomes increasingly consumed with her vision of Agnes as both subject and symbol—someone who bridges generations and might hold the key to a new revelation.

At the same time, Agnes begins to question not just the motivations of Nora but also the assumptions she herself holds about her family. What if her grandfather wasn’t guilty?

What if he was? What if she never really knew her father or grandmother at all?

Ása’s story becomes a spectral thread through the novel. Her disappearance echoes the violence of the past, and her brief, frenzied perspective reveals a young woman trapped in cycles of powerlessness and silence.

Her vanishing doesn’t just stir public interest or journalistic intrigue—it activates personal hauntings in Agnes, whose resemblance to Ása and Marie makes her central to both women’s stories. In this way, the novel gradually uncovers not just crimes but identities, examining how stories are told, remembered, and revised across generations.

Ultimately, The Lost House builds its narrative around a sense of emotional and psychological isolation, using the cold, remote Icelandic setting to mirror the internal landscapes of its characters. As the investigation intensifies, Agnes must decide whether she is willing to accept the truths it reveals—about her family, her addiction, her pain, and her place in a legacy of disappearance and death.

The novel refuses easy resolutions, emphasizing instead the ambiguity of memory and the costs of storytelling, especially when those stories are built on other people’s tragedies. Agnes becomes both seeker and subject, haunted not just by ghosts of the past, but by the demands of the present and the unknowable weight of what lies beneath the snow.

Characters

Ása Gunnarsdóttir

Ása is a deeply troubled young woman whose psychological unraveling opens the novel with a sense of immediate urgency and dread. Her character is defined by emotional instability, substance dependence, and a desperate need to reclaim some semblance of control over her pain.

At the party where she’s first introduced, Ása stands apart from the crowd—not due to arrogance or detachment but because of the quiet storm within her. Her fixation on sending the malicious text message, “I hope I haunt you,” reveals both her pain and her latent desire for revenge or acknowledgment.

The message, meant for someone who has clearly hurt her, is less about confrontation and more about legacy—about leaving behind a wound or memory that persists even in her absence. Her relationship with Lilja, who appears both concerned and possessive, and the reference to Óskar, suggests a web of toxic emotional dependencies in which Ása is ensnared.

Her final decision to leave the party and stumble into the snow-laced wilderness is both a literal and metaphorical escape—from noise, control, betrayal, and perhaps even life itself. Her experience of hearing a voice and then being pulled from the snow introduces a spectral ambiguity to her story, blurring lines between the psychological, the supernatural, and the criminal.

As the narrative progresses, Ása’s disappearance becomes not just a tragedy but a clue to a wider and older mystery, adding layers of resonance to her ghost-like final moments.

Agnes Glin

Agnes Glin arrives in Iceland carrying a fragile mix of resolve, grief, and physical pain. She is a woman who has already endured much: a devastating surfing accident that ended a promising chapter of her life, an addiction to opioids that reveals a long and lonely recovery, and a fractured family history built on the skeleton of a murder she only partially understands.

Her determination to reclaim the story of her grandmother and infant aunt’s brutal deaths adds dimension to her personality—it isn’t just about truth, but about rewriting the inheritance of silence and suspicion she’s lived with. Agnes is deeply ambivalent about her father, Magnús, who views her involvement in the podcast as a betrayal, and this tension reflects her desire to assert her autonomy while still seeking emotional closure.

Her initial reluctance to engage with the podcast, despite being its central figure, highlights the internal conflict she feels about exposing long-buried trauma. Agnes is not a traditional heroine; she’s vulnerable, flawed, and often overwhelmed, but this only makes her more compelling.

Her resemblance to her grandmother, Marie Hvass, both complicates her journey and turns her into a living symbol of the unresolved case. As Nora begins to speculate about the connections between past and present, Agnes becomes a pivotal figure caught in the chilling crosscurrents of familial legacy and potential danger.

Her story is one of confronting inherited trauma and asserting truth amid a fog of guilt, grief, and fear.

Nora Carver

Nora Carver is the charismatic and obsessive engine behind the true crime podcast The End. She is portrayed as both brilliant and borderline compulsive—someone whose intellect is matched only by her hunger for revelation.

Nora is not just a passive observer of crime; she’s an active participant in re-framing narratives and shifting public perceptions. Her previous success in solving a murder case in California adds to her reputation, but it also explains the heightened pressure she puts on herself now that she’s in Iceland.

Her fascination with the Frozen Madonna and Child case borders on the eerie, particularly when she fixates on Agnes’s resemblance to Marie. This obsessive streak paints Nora as someone who not only reports on the macabre but is drawn to it viscerally.

Her renting of a home built on Einar Pálsson’s former land is symbolic—it shows her desire to inhabit the story, to live within the bones of it rather than simply tell it from a distance. Nora’s dedication to truth is real, but it’s also filtered through her awareness that truth in the realm of memory and emotion is slippery and mutable.

She acknowledges that “the truth might be rare and flexible,” suggesting a self-awareness that tempers her obsession. Despite her intensity, Nora is also a source of insight and momentum; she brings clarity to Agnes’s fragmented understanding of the case and shifts the story from cold case to present danger with her recognition of Ása’s disappearance.

She is both detective and provocateur, operating in the liminal space between storytelling and investigation.

Lilja

Lilja, though a secondary character, plays a crucial role in illuminating Ása’s deteriorating emotional world. She appears as a concerned friend, hovering on the edge of Ása’s personal chaos, trying to maintain a semblance of normalcy while being both drawn to and exasperated by Ása’s instability.

Her presence at the party and her attempts to engage Ása signal a mix of empathy and codependency. There’s a tension in their relationship—Lilja is needy and perhaps even controlling, while Ása is unreachable, lost in her own torment.

This emotional friction between them enhances the atmosphere of unease that characterizes Ása’s final moments at the party. Lilja functions as both a witness and a failed protector, someone who may later carry the weight of what she did or didn’t do on that pivotal night.

Her emotional investment in Ása’s wellbeing contrasts with the futility of her efforts, capturing the tragedy of trying—and failing—to save someone from themselves.

Magnús

Magnús, Agnes’s father, remains a shadowy but emotionally powerful figure in the narrative. His opposition to Agnes’s involvement in the podcast is not just protective—it’s deeply personal, rooted in his own fractured relationship with the past.

Magnús is a man burdened by the inherited shame and public suspicion surrounding his father, Einar Pálsson. His desire to leave the past buried and his frustration with Agnes’s quest suggests a man who has tried to build a life from denial.

His emotional distance from Agnes and his failure to address her grief and addiction reflect a generational disconnect, one that adds emotional depth to the story. Magnús is not unsympathetic—he’s a product of the trauma he refuses to fully confront.

His resistance underscores the novel’s larger theme: the difficulty and danger of unearthing buried truths, especially when those truths implicate the very foundations of family identity.

Einar Pálsson

Though Einar Pálsson does not appear directly in the present timeline, his presence looms over the narrative like a specter. He is the man around whom the original mystery revolves—a grandfather accused but never convicted of a gruesome double murder.

To the town, he is a symbol of guilt and unresolved violence; to his family, he is an enigma clouded by shame, silence, and the incomplete truths handed down over generations. Agnes’s desire to exonerate him and reclaim a fuller understanding of his character turns Einar into a focal point of inquiry and myth.

Whether guilty or not, Einar’s legacy is already stained, and his absence is as telling as his presumed actions. He represents the unknowable past, the way stories ossify into assumptions when no one remains to tell them anew.

Through Agnes’s investigation and Nora’s obsession, Einar becomes not just a possible killer but a cipher through which questions of memory, justice, and familial inheritance are filtered.

Themes

Haunting and Psychological Disintegration

The Lost House foregrounds the theme of haunting not merely through supernatural suggestion, but through psychological collapse and the lingering grip of unresolved trauma. Ása’s narrative exemplifies this most strikingly: intoxicated, disoriented, and emotionally wrecked, she is not haunted by a ghost, but by the crushing weight of emotional betrayal and an almost dissociative identity crisis.

Her desire to send a venomous message—“I hope I haunt you”—sets a chilling tone, positioning her as both victim and potential specter. This notion of becoming the thing that disturbs others reflects her unraveling self-concept, distorted by pain and an inability to process the betrayal she’s experienced.

Her hallucinations in the snow, where she hears a man calling her and is then dragged from the freezing landscape, blurs the line between danger and rescue, real threat and imagined menace. The motif of haunting reverberates later in Agnes’s storyline as well, where the past—the violent murder of her grandmother and infant aunt—reaches into the present.

Agnes herself becomes a kind of ghost, especially in the eyes of Nora Carver, who is unnerved by her eerie resemblance to Marie. Here, the haunting is generational, inherited, and impossible to escape.

Both women are shaped by events they can neither fully remember nor forget, echoing the way trauma functions—less like a scar and more like an open wound. In this world, to be haunted is not just to see visions or hear voices; it is to be gripped by a memory so unresolved that it becomes an active force, dictating action and identity.

Grief and Generational Inheritance

Grief in The Lost House operates on both an individual and a generational level. Agnes arrives in Iceland grappling with multiple forms of loss: the physical pain of a surfing injury that ended her athletic life, the psychological toll of opioid dependency, and the emotional burden of losing family members she never met but whose deaths have shaped her existence.

Her decision to engage in the podcast investigation is not only an attempt at truth-finding but also a method of processing her grief—a ritual of reclamation. This grief is not hers alone; it is bequeathed to her, passed down through silences and half-truths by her father, Magnús, who is resentful and emotionally opaque.

Magnús represents an earlier generation’s desire to bury pain under denial, while Agnes’s quest symbolizes a more contemporary impulse to interrogate and uncover. Similarly, Nora Carver’s obsession with the case isn’t just professional; it’s an emotional investment in resolving loss that may never have directly affected her but resonates deeply.

Ása’s disappearance decades later triggers a collective echo of that earlier trauma, extending the reach of grief even further into the present. The novel does not position grief as something that can be neatly resolved; rather, it explores how it festers in secrecy, poisons relationships, and demands acknowledgment.

Agnes’s confrontation with both personal and inherited grief forms a central emotional arc of the story, revealing how loss that is not mourned honestly becomes embedded in identity and behavior, replicating its effects across time.

Memory, Truth, and the Distortion of Narrative

One of the most complex themes in The Lost House is the instability of memory and the subjective nature of truth. From the outset, the characters are embroiled in a narrative that resists linearity or certainty.

Agnes has grown up with a carefully curated version of events surrounding the Frozen Madonna and Child case, one dictated by her father and sanitized to preserve familial loyalty. Her arrival in Iceland, and her collaboration with Nora, forces her to confront the gaps, omissions, and contradictions in that story.

Nora, although portrayed as rigorous and well-intentioned, openly admits that truth is “rare and flexible,” suggesting that even her investigative process is tinged with bias, ambition, and narrative framing. Memory is also destabilized through Ása’s experiences; her drunken hallucinations, blurred perceptions, and sense of disconnection from reality undermine the possibility of accurate recall.

The novel frequently situates memory as a contested space, where emotional truth and factual truth often diverge. The use of podcasting as a narrative frame further complicates this theme, reflecting modern media’s role in constructing and disseminating truth through selective storytelling.

In The Lost House, no one is a wholly reliable narrator—not Agnes, not Nora, not even the records of the past—and this ambiguity fuels the novel’s emotional tension. It asks whether it is possible to arrive at truth through fractured memory and inherited trauma, or whether all narratives are approximations shaped as much by desire and guilt as by fact.

Female Identity, Agency, and Objectification

Throughout The Lost House, the depiction of female characters interrogates themes of identity, autonomy, and the ways in which women are often reduced to symbols or objects of fascination. Ása’s opening scenes portray her as overwhelmed and violated by the emotional demands of those around her—especially by the unspoken tensions with Lilja and Óskar.

Her identity seems to collapse under these pressures, and her disappearance becomes not just a plot device, but a representation of how female suffering can be both intimate and public spectacle. Agnes, meanwhile, navigates a world in which her body and story are subjected to scrutiny—whether from Nora, who treats her like a reincarnation of Marie, or from the public eye through the podcast.

Nora herself, despite her professional acumen, is portrayed as obsessive and performative, casting doubt on whether her pursuit of justice is truly altruistic or another form of self-serving spectacle-making. The eerie resemblance between Agnes and her grandmother furthers the theme of women being aestheticized or mythologized rather than understood.

Even the phrase “Frozen Madonna and Child” transforms a gruesome murder into an iconographic image, stripping it of its horror in favor of haunting symbolism. In this world, women’s experiences—of pain, addiction, loss—are repeatedly consumed, reshaped, and framed by others.

The novel critiques this dynamic by centering the emotional and psychological realities of its female characters, refusing to let their stories be simplified or romanticized by outsiders.

The Intersection of Crime, Spectacle, and Ethics

The ethics of crime investigation, particularly in the age of true crime media, is another central theme that The Lost House explores with a sharp and often uncomfortable lens. Nora Carver’s role as a celebrated podcaster complicates the boundaries between justice-seeking and exploitation.

Her previous success in solving a cold case in California lends her credibility, but her intensity in Iceland suggests something more volatile—a blend of obsession, performance, and entitlement. By building a luxurious home atop the land tied to Agnes’s family history, she physically inserts herself into the crime scene in a way that borders on invasive.

The spectacle of true crime becomes a driving force in the story, with Nora orchestrating a narrative that is meant to grip listeners, generate clicks, and perhaps exonerate or condemn with the sweep of an edit. Agnes’s own involvement is fraught with ambivalence; she is at once a participant and a subject, caught in the glare of a media machine that thrives on suffering.

The ethical question at the heart of the novel is whether justice can truly be served when the telling of a story becomes commodified. As Ása’s case unfolds and parallels emerge between past and present, the investigation begins to resemble a feedback loop of violence, grief, and voyeurism.

The narrative critiques how easily the line between investigation and entertainment is blurred, and how real human anguish is often reshaped into consumable content, undermining the integrity of truth in the process.