The Lotus Empire Summary, Characters and Themes

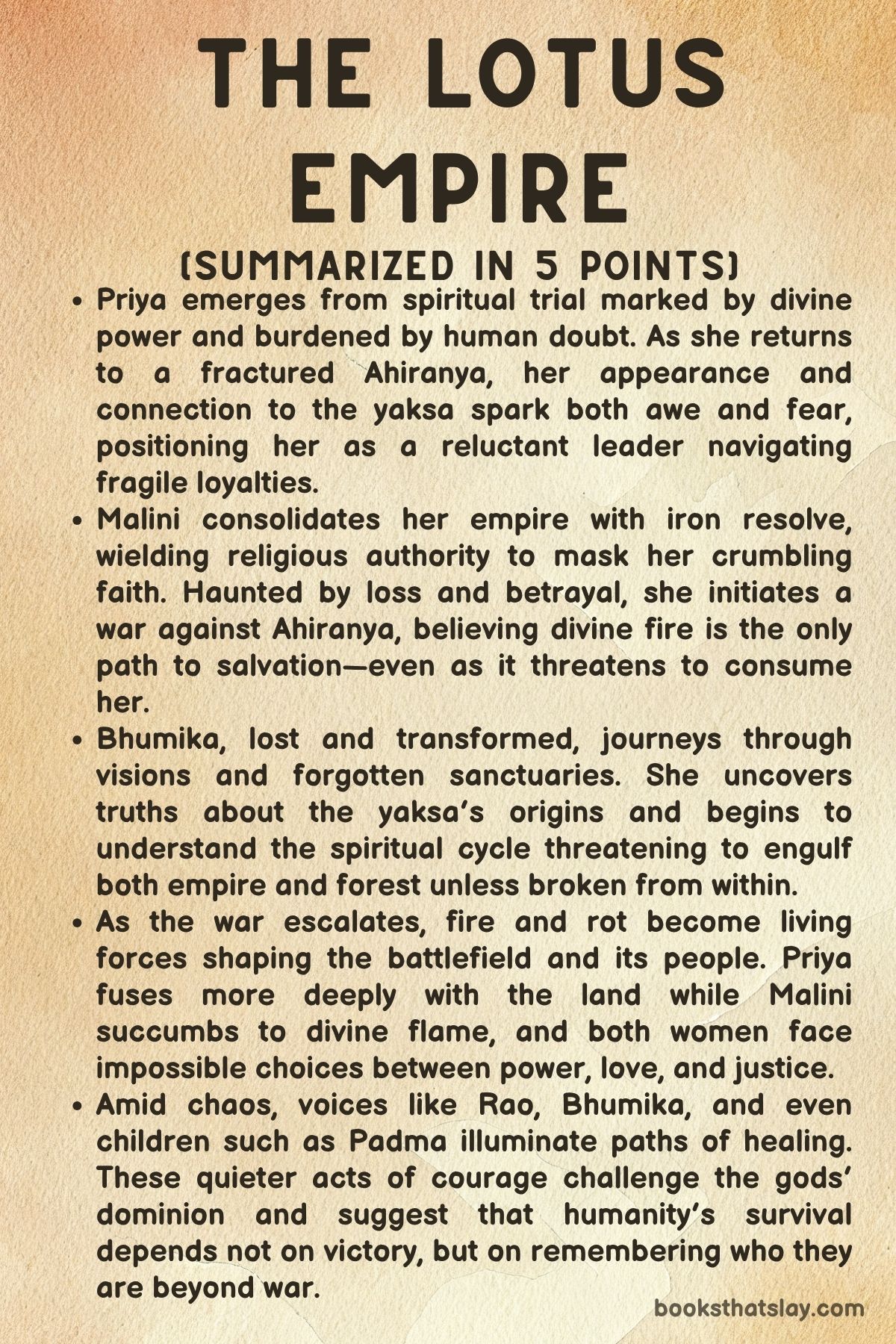

The Lotus Empire by Tasha Suri is the finale to her Burning Kingdoms trilogy, a work of fantasy fiction that explores themes of power, faith, love, identity, and the costs of transformation in a war-ravaged empire. Told through the perspectives of several central characters—Priya, Malini, Bhumika, Rao, and others—it continues the journey of personal and political reckoning initiated in the previous books.

Suri blends divine myth with human struggle, exploring how broken systems are rebuilt or undone by the people who survive them. With divine beings, forest spirits, and the lingering consequences of conquest, the novel chronicles a world on the brink of change, where power may come from godhood, but salvation requires humanity.

Summary

The story begins with a sense of rising unease. Divyanshi, a girl grieving her father’s death, embarks on a desperate pilgrimage during the monsoon to seek divine justice from the fire god believed to dwell in the mountains.

At a sacred lake, she is visited by a mysterious flame that answers her prayer with a new pact. This supernatural opening foreshadows a larger reckoning—the fire god’s return will reshape both empires and individuals.

Meanwhile, Priya—once a priestess and now High Elder of Ahiranya—is caught in a liminal space between human and divine. After surviving betrayal, war, and spiritual communion with the ancient yaksa spirits, she struggles to lead a wounded people.

The yaksa, elemental beings tied to forest and rot, see Priya as their vessel, transforming her physically and spiritually. Flowers bloom from her skin, her eyes glint with unnatural green, and she becomes a living channel for the forgotten god Mani Ara.

Yet Priya resents the power she has been given and mourns what she has lost, especially her sister Bhumika and her former lover Malini. Haunted by guilt and divine voices, she forges ahead, torn between duty and an aching desire for peace.

Malini, now Empress of Parijatdvipa, is likewise transformed. Scarred by betrayal and fire, she rules through cold precision and political strategy.

Grief for her brother Aditya simmers beneath her hardened surface. She executes traitors, manipulates religious fanatics, and co-opts former enemies to consolidate control.

Yet she is not without vulnerability. Her longing for Priya lingers, manifesting in dreams and aching silences.

Malini’s leadership becomes a mirror to Priya’s—both women navigating power shaped by pain, both unable to forget each other.

Rao, the former general once close to both women, wanders in a haze of grief and disillusionment. He mourns Aditya and the fallen empire they once believed in.

When he reunites briefly with Sima, a comrade imprisoned for resisting imperial rule, he glimpses the wreckage left by war. Yet Rao too is pulled toward a divine calling—visions of fire, fate, and unfinished duty push him toward a monastery, where he hears of Bhumika’s survival.

Bhumika, long thought dead, awakens in obscurity with no memory of her past. Nursed back to health by a stranger who claims to be her husband, she receives a vision from river-spirits and begins to recall fragments of her former life.

She learns she once bore a daughter who still lives. As she journeys toward Alor, a sacred land tied to the yaksa, Bhumika reclaims her identity.

Her memories return with the whispers of the divine, and she realizes that knowledge—painful, sacred, and hidden—may be the key to ending the gods’ hold on the world.

The narrative accelerates as Priya prepares for a confrontation with Malini. She meets the child Padma and Rukh, sharing quiet moments that underline her isolation.

Yet she is no longer just a leader—she is a god’s vessel. The yaksa grant her a sacred crown mask and intensify their influence.

Though she is Mani Ara’s chosen, Priya remains uncertain and increasingly disillusioned, doubting the very god that possesses her. When Malini advances with fire magic and an army, Priya fortifies the forest, steeling herself for war.

Malini, fueled by betrayal and rage, prepares to burn the forest sacred to the yaksa. Her connection with Priya, though strained by betrayal and political divergence, still haunts her.

She brings with her a weapon forged from the heart’s shell—black stone capable of nullifying yaksa magic. Her soldiers and priests wield this deadly innovation, a sign that faith has been transformed into something sharper and more cynical.

As the armies clash, Priya suffers a psychic wound. Her closest ally, Ganam, is stabbed with a heart’s-shell dagger.

Priya’s grief unleashes an elemental fury. She annihilates the attackers and accepts a fuller merging with Mani Ara.

Flowers and rot bloom around her as she sinks into divine transformation. But the yaksa’s joy at her growing power troubles her.

She senses they are consuming her humanity. Determined to find another way, Priya descends into the deathless waters of the sangam to confront Mani Ara directly.

Elsewhere, Bhumika warns a village of the yaksa’s awakening. The villagers are fearful but hesitant.

She pleads for unity, knowing the divine threat is too great to face alone. Rao, following Bhumika’s trail, arrives at a monastery that had previously turned her away.

He learns of her warnings and resolves to stand against the growing danger.

The climactic moments unfold in rapid succession. Malini captures Priya using enchanted jewelry and a blade.

Priya, consumed by rot, can only surrender. Yet love and recognition flicker between them.

Despite everything, Malini cannot kill Priya. Instead, she carries her toward the sacred waters, hoping for a miracle.

As Malini hauls the dying Priya across hostile terrain, Priya’s magic creates vines to cradle her. At the Hirana’s mouth, Malini opens the water’s gate using Priya’s power, carrying her into the sanctum.

Priya disappears beneath the surface, where she confronts Mani Ara in full. Mani Ara urges her to merge completely, but Priya refuses.

Recognizing that divinity without humanity only causes pain, she unravels the sangam, collapsing the divine conduit that grants unnatural rebirth. This unmaking ends the cycle of divine possession, leaving only enough magic to protect a few survivors.

Bhumika, on the cliffs above, reunites with her daughter Padma and watches as the remaining yaksa accept their end. Arahli Ara merges with Bhumika briefly, restoring her identity before joining the others in death.

Rao slays Hemanth, the last priest of zealotry, with grim resolve, ending the theocratic threat.

Malini emerges from the waters with Priya’s body. The empire is changed.

The yaksa are gone. Ahiranya gains its independence.

Priya is presumed dead, and Malini rules alone, transformed but hollow. Rao declares her divine, but her soul aches for the woman she could not save.

Years later, signs of Priya’s survival emerge—flowers blooming unnaturally. Malini relinquishes power and journeys into the forest.

In a hidden grove, she finds Priya again—changed, mortal, yet alive. They reunite quietly, with no need for thrones, magic, or war.

Bhumika also sees Priya again, closing the story not with triumph, but with quiet survival and the enduring promise of love. The lotus empire is reborn—not as a dominion of gods, but as a world shaped by memory, courage, and human choice.

Characters

Priya

Priya is the emotional and mythic center of The Lotus Empire, a woman both mortal and divine, whose transformation unfolds across physical, spiritual, and emotional dimensions. Once a healer and rebel, Priya rises to become the thrice-born High Elder of Ahiranya, imbued with the elemental power of rot and regrowth.

Her connection to the yaksa and to the divine being Mani Ara is not merely symbolic—it is bodily and existential, reshaping her into a vessel of incredible, often terrifying, magic. Yet beneath this divine evolution lies a profoundly human struggle.

Priya mourns her lost relationships, especially with her sister Bhumika and her lover Malini, and battles the unbearable weight of leadership thrust upon her. Her identity constantly fragments and reforms under pressure—whether from political responsibility, divine expectation, or personal guilt.

She is torn between love and duty, anger and compassion, humanity and godhood. Priya’s character arc is steeped in grief but also resilience; though the rot threatens to consume her, she seeks a third path: one that protects her people, honors her own emotions, and resists the cycle of divine consumption.

Even when she descends into the waters to merge with Mani Ara, she chooses self-sacrifice over domination, and in doing so, reclaims her individuality and her love for Malini. By the novel’s end, she has shed her divinity but remains deeply changed, reemerging as something both mortal and mythic—proof that transformation does not mean erasure.

Malini

Malini, the Empress of Parijatdvipa, is a figure of ruthless authority and buried longing. From the ashes of betrayal and war, she forges herself into a cold, unyielding sovereign who sacrifices friends, lovers, and spiritual ideals in her pursuit of control.

Her pain is sculpted into policy, her trauma into strategy. Yet for all her calculated executions and manipulations, Malini is not without vulnerability.

She is haunted by her love for Priya, a connection that lingers in dreams and silence even as she commands an army to destroy the sacred forests of Ahiranya. Her faith, once pure, becomes political theater, and her vengeance is wrapped in ceremonial fire.

Yet when confronted with Priya in the flesh—wounded, radiant, and godlike—Malini falters. She cannot kill her.

This act of restraint, rare for a ruler who buried a zealot alive without hesitation, reveals the depth of her conflicted heart. Her journey is marked by loss: of family, of certainty, of the woman she once was.

But through it, she gains clarity about what she truly values. In carrying Priya through the Hirana and standing by her during the unmaking of the sangam, Malini surrenders control for love.

By the end, she relinquishes power not out of weakness, but in recognition that true rule demands more than dominance—it requires understanding, sacrifice, and release. Her final reunion with Priya, set in a quiet, blooming grove, is a gesture of redemption and renewal, closing the gap between empress and woman, lover and beloved.

Bhumika

Bhumika, once believed dead, returns to the story as a ghost of herself—fragile, fragmented, and physically worn down by illness and memory loss. Yet her reemergence is a quiet triumph.

She is no longer the High Elder or the guiding force she once was, but her moral clarity and intuitive strength remain undiminished. Her connection to the yaksa is less about power and more about knowledge, memory, and maternal reckoning.

Through her journey, Bhumika uncovers forgotten truths, including the existence of her daughter Padma, and reclaims parts of herself that had been stripped away by war and trauma. Her relationship with Jeevan, though tinged with complexity, offers a temporary sanctuary, but she is ultimately drawn back to the spiritual heart of the conflict.

Her role in confronting the final remnants of the yaksa reveals her emotional depth and her willingness to stand for others despite her own pain. When she reunites with Padma and receives Arahli Ara’s final gift, Bhumika becomes the custodian of memory and identity—living proof that healing is possible, even after profound fragmentation.

She bridges the human and the divine not through magic, but through presence, wisdom, and quiet endurance. In the end, Bhumika becomes a vessel not of power, but of peace—a spiritual witness to rebirth, sacrifice, and reunion.

Rao

Rao’s arc in The Lotus Empire is one of descent and tempered return. Once a general and close confidant of both Priya and Malini, Rao is driven by loss—of comrades, ideals, and purpose.

Grief consumes him, especially after Aditya’s death, pushing him into isolation and heavy drinking. But Rao is not broken; he is searching.

His journey becomes one of faith, not in gods or empires, but in people. His reunion with Sima reflects the painful fractures left by war, where former allies are transformed into prisoners or strangers.

Rao is plagued by visions and divine hints, suggesting that something greater still stirs within him. His eventual confrontation with Hemanth is a crucial moment: Rao does not strike in righteous anger but in weary necessity.

He kills not to uphold belief but to stop further destruction. In this, he transcends the binary of sacred and profane, choosing a pragmatic compassion rooted in human survival.

Declaring Malini a living goddess is less an act of fanaticism and more a political move to secure stability. Yet Rao, more than most, sees the cost behind the myth.

His survival, unlike others, is not mythic or magical but grounded—he is the soldier who endures, the friend who remains. Rao stands as a reminder that even amidst divine battles, human courage still matters.

Jeevan

Jeevan, the quiet companion of Bhumika during her time in hiding, is a character shaped by loyalty, gentleness, and unspoken sorrow. Posing as Bhumika’s husband, he offers her protection and care without demanding gratitude or explanation.

His love for her is steady and sacrificial—he stays even as she is haunted, sick, and only half herself. Yet his relationship with Bhumika is marked by distance, underscoring the emotional gulf caused by memory and loss.

He is not Padma’s father, and he knows it. He is a placeholder in a narrative far larger than himself.

And yet, his presence is deeply important. He allows Bhumika the space to remember and reclaim herself.

Jeevan is a rare figure in a world of grand battles and divine interventions—a man who chooses love without possession, care without condition. When he walks beside Bhumika toward danger, he exemplifies quiet bravery.

Though not central to the mythic structure, Jeevan is essential to the emotional landscape of the story.

Ganam

Ganam, Priya’s most loyal warrior and friend, is a character forged in the crucible of belief and battle. His relationship with Priya transcends simple hierarchy—it is built on deep trust, shared ideals, and mutual sacrifice.

He follows her into danger without question and suffers greatly for it, wounded by heart’s shell and nearly dying in her arms. His injury becomes the trigger for Priya’s full embrace of Mani Ara, a moment that highlights both his importance and the tragic costs of divine power.

Ganam’s presence humanizes Priya, grounding her in loyalty and shared history even as she ascends toward godhood. He survives the war, scarred but alive, a symbol of resistance and resilience.

Though never in the spotlight, Ganam’s steadiness, humility, and endurance serve as a counterpoint to the grandeur of prophecy and leadership. He is a reminder of the human cost of revolution and the loyalty that outlasts even divine upheaval.

Themes

Divine Authority and Mortal Agency

The struggle between divine will and human autonomy forms the spiritual and political foundation of The Lotus Empire. Characters such as Priya, Bhumika, and Malini are constantly navigating the chasm between what is expected of them by divine entities—such as the yaksa—and what they desire for themselves or their people.

Priya’s journey is emblematic of this conflict. As the chosen vessel of Mani Ara, she is revered, burdened, and feared, but her relationship with the divine is fraught with confusion and resistance.

Her transformation, from a woman of the forest to a near-godlike figure adorned in flowers and rot, represents a literal embodiment of divine power. However, her deepest struggle remains one of choice: whether to allow herself to be subsumed by Mani Ara’s will or to find a new path that preserves her humanity.

Malini, by contrast, manipulates divine narratives to cement her authority. Her rule relies on a manufactured image of holiness and righteous vengeance, even as she has lost personal faith.

The divine becomes a political tool, used to punish or inspire, rather than a source of truth. Meanwhile, the yaksa, once revered and feared as ancient divinities, are slowly unmasked as beings whose continued existence brings devastation.

Bhumika’s final confrontation with them results not in worship but in mutual recognition of their obsolescence. The novel constantly questions the legitimacy of divine rule, especially when it demands the erasure of individual desire and identity.

In the end, it is Priya’s defiance of divine absorption—her choice to unmake the sangam and preserve human agency—that asserts mortal self-determination as the most sacred force.

Grief, Memory, and Identity

Throughout The Lotus Empire, grief is both an emotional reality and a metaphysical force shaping identity and action. Characters are haunted not only by those they have lost but by the versions of themselves that perished in the process.

Malini mourns her brother Aditya, but also the woman she was before power, war, and betrayal hardened her. Her pain is not private—it is spectacle, political pageantry, and also an intimate wound that festers in her dreams of Priya.

Priya grieves Bhumika and the loss of her previous self, a woman who loved and led with gentleness rather than elemental fury. Her transformation into a bearer of rot and divine essence threatens to erase the tender, human parts of her soul.

Bhumika, long presumed dead, carries grief in her fragmented memories and in the revelation of a lost child. When she drinks from the river and recalls her daughter Padma, it is a visceral reconstitution of identity through mourning.

Her memory is incomplete, but the ache of loss makes her whole again. Rao, once a loyal general, is broken by grief and guilt, unable to find solace even in divine visions.

These characters are shaped and reshaped by their sorrow, which defines the contours of their decisions. Grief is not static—it is transformative.

It births vengeance, wisdom, resilience, and, sometimes, the courage to let go. In the final acts, grief gives way to a fragile peace, not because it disappears, but because the characters have made space for it within themselves, allowing it to coexist with hope and rebirth.

Power, Sacrifice, and Moral Ambiguity

Power in The Lotus Empire is never pure—it is always accompanied by sacrifice, and rarely allows for clean moral lines. Malini, as Empress, becomes increasingly authoritarian.

Her rule is efficient, pragmatic, and deeply compromised. She manipulates old enemies, executes with cold precision, and discards loyalty when it endangers her rule.

Yet her actions stem from a desperate desire to protect, to control a world that has repeatedly betrayed her. Priya’s power is more spiritual, but no less dangerous.

As a vessel of the yaksa, her body becomes a weapon, her magic a threat to the very people she seeks to save. Her arc is marked by moments of terrifying destruction, driven by rage and love alike.

She annihilates soldiers not with strategic intent but emotional eruption, demonstrating how power, when rooted in grief or fury, can become a blunt and dangerous force. Bhumika sacrifices safety and anonymity to rejoin the battle for her homeland, accepting the cost of exposure in exchange for knowledge and solidarity.

Even Rao, whose choices seem less grand, sacrifices his moral compass to end Hemanth’s life—not as a hero, but as a man cornered by necessity. The novel resists the notion of righteous power.

Every decision carries cost; every victory leaves scars. Sacrifice becomes the currency of leadership, and the burden is heaviest on those who still possess empathy.

In this world, moral purity is a myth. What matters is who bears the cost, and whether the wielders of power can live with the consequences of what they’ve done to survive.

Queer Love and Devotion

The relationship between Priya and Malini is a poignant, volatile core to the narrative of The Lotus Empire. Their connection transcends politics and magic—it is an intimate bond shaped by betrayal, yearning, and the painful residue of love fractured by circumstance.

They are not simply lovers separated by war; they are representations of two competing visions of salvation. Malini wants to reshape the world by wielding fire, power, and ruthlessness.

Priya seeks to protect it by becoming something ancient and wild. Their desire for each other never disappears, but it becomes more complicated with every act of political aggression or spiritual transformation.

When they finally reunite, it is not with clarity but with contradiction: Malini cannot bring herself to kill Priya, even when given the means to do so. Priya, despite her divine evolution, still aches when she hears Malini’s voice.

Their love is not redemptive in a simple sense—it is a battleground of its own. But it is also a form of devotion that survives divine disillusionment and imperial ambition.

In the novel’s final moments, this queer love becomes a quiet answer to the chaos of war and politics. They reunite, not as ruler and elder, or goddess and weapon, but as two women who have endured everything and still reach for each other.

Their love is not presented as idyllic or all-healing—it is flawed, bruised, and born of conflict. But it remains enduring, and in a world where everything else has crumbled, that endurance becomes its own kind of grace.

Rebirth, Rot, and the Natural World

Nature is not a passive background in The Lotus Empire—it is an active, divine participant. Rot is not decay in the usual sense, but a sacred, cyclical force that powers transformation, death, and renewal.

Priya’s magic is expressed through rot—flowers blooming from her wounds, trees erupting from her footsteps. Her communion with the yaksa makes her a conduit for the natural world’s mystical properties.

But the rot is dangerous too; it threatens to overwhelm, to unmake order and drown reason in instinct and chaos. The yaksa themselves are ancient beings of nature, embodiments of forces beyond human comprehension.

Their presence signals disruption and rebirth, but also destruction. Bhumika’s encounter with the river spirit and her eventual merging with Arahli underscores the natural world as a bearer of memory, lineage, and divine essence.

Water carries memory; rot holds truth. Even Malini, with her fire magic, is forced to confront the limits of her power when faced with the dense, breathing wilderness of Ahiranya.

The forest is not simply terrain—it is resistance. The theme of rebirth is also evident in the conclusion, where the collapse of the sangam and the death of the yaksa signify not extinction but regeneration.

Priya reemerges, not as a deity, but as something new—changed, still wild, but more human. The natural world in this novel is not merely a setting, but a character: wrathful, maternal, and sacred.

Its cycles of rot and bloom echo the characters’ own transformations, making nature both a mirror and a master of fate.