The Lotus Shoes Summary, Characters and Themes

The Lotus Shoes by Jane Yang is a haunting and deeply personal exploration of servitude, resilience, and self-worth in late Qing dynasty China. It tells the story of Little Flower, a young girl sold into slavery, and her journey from silent obedience to fierce independence.

Through her eyes, we witness the oppressive systems of foot-binding, patriarchy, and class that define and deform the lives of women. The novel is not only a record of historical injustice but also a powerful meditation on agency, friendship, and transformation. Yang’s narrative gives voice to girls historically silenced, presenting a sobering portrait of strength amid systemic cruelty.

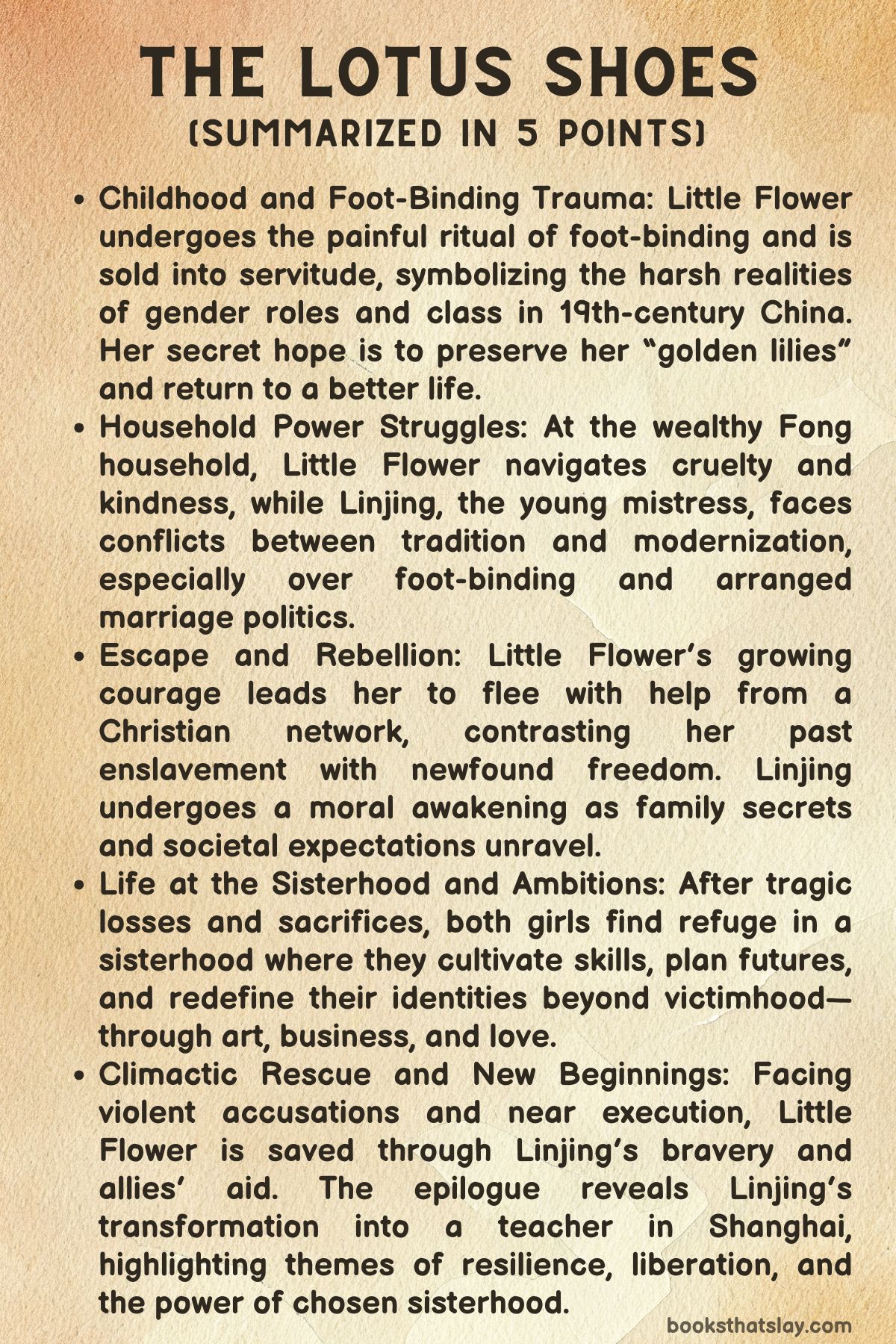

Summary

Little Flower is six years old when her mother, Aa Noeng, sells her into servitude under the guise of a journey to the city. In the harsh winter, they travel to Canton City, where Little Flower is handed over to the wealthy Fong family as a muizai—a lifelong bondmaid.

The betrayal is devastating, made worse by the fact that Aa Noeng frames it as an act of love. Before delivering her daughter, she insists on binding Little Flower’s feet, a brutal tradition seen as essential for a girl’s future prospects.

The pain is framed as a pathway to upward mobility, but Little Flower quickly learns that her destiny is not marriage but slavery.

Within the Fong household, Little Flower is assigned to serve Linjing, the daughter of the family. Linjing, though born into privilege, feels neglected and is jealous of any affection Little Flower receives, especially from her own mother.

This jealousy results in constant bullying and culminates in the undoing of Little Flower’s foot-binding—an act that strips her of the one thing that might have helped her escape servitude. Nonetheless, Little Flower clings to hope.

She secretly continues to bind her feet and dreams of a future reunion with her mother.

Though Linjing is cruel, she too is trapped. Promised in marriage to a progressive nobleman who opposes foot-binding, Linjing is alienated from her conservative family.

Her father sees her as a tool in his political ambitions, while her grandmother, Maa Maa, resents her unbound feet. Both girls are prisoners of societal expectations: one through bondage, the other through arranged marriage.

As they grow, their rivalry deepens, but so does their uneasy dependence.

Little Flower finds friendship and solidarity in Spring Rain, another servant. The two girls steal moments of freedom during monthly outings and pray at the shrine of Jyut Lou, the marriage deity, each wishing for a way out.

Little Flower pours her longing into embroidery, creating exquisite designs that offer her dignity and value beyond her status. Spring Rain, desperate and abused, plans an escape during a banquet by fleeing with a traveling opera troupe.

Despite their frictions, Little Flower promises to help fund her escape and protect her secret, demonstrating the strength of their chosen bond.

The power dynamic between Linjing and Little Flower worsens when an American tutor, Miss Hart, praises Little Flower’s embroidery skills. Linjing, unable to perceive red and green, is embarrassed and retaliates by forcing Little Flower to destroy her bridal quilt—a symbol of her hopes.

This act marks a turning point. Little Flower begins secretly selling embroidered handkerchiefs, aided by Miss Hart, to raise money for Spring Rain.

Though Spring Rain distrusts foreigners, blaming them for her father’s opium addiction, Little Flower is willing to take risks for any chance at freedom.

Linjing’s downfall begins with a scandal involving her mother, Phoenix (Aa Noeng). After a power struggle within the Fong household, Linjing awakens to learn her family has been disgraced.

Peony, her father’s concubine, now holds power and declares Linjing and her mother dead from smallpox. Phoenix, to save her daughter from exile to a remote nunnery, ingests hemlock.

Though Linjing feels betrayed, her mother’s final letter reveals the sacrifice was meant to preserve her dignity.

Linjing and Little Flower are then sent to the Celibate Sisterhood to work in a silk reeling factory. The labor is exhausting and degrading.

While Little Flower quickly adapts and works diligently, Linjing clings to old hierarchies and becomes emotionally dependent on her former maid. Their relationship ruptures when Little Flower, emboldened by the more egalitarian environment, tears up her indenture paper and declares herself free.

Linjing is shaken but slowly begins to see the need to stand on her own.

As Linjing struggles, she fixates on Noble Siu Je, the kind but distant factory owner. She believes marriage to him will restore her status.

Meanwhile, Little Flower presents him with her embroidery, hoping to join his shawl project. Though impressed, he dismisses her due to her unbound feet, assuming a low-status woman could not have such talent.

The rejection stings, reinforcing the cruelty of class-based assumptions.

Linjing’s obsession with Noble intensifies. She misreads polite gestures as affection and shares her hopes with Little Flower, who remains silent out of caution.

Both women become involved in preparations for the Seven Sisters Festival, where Linjing’s longing for security contrasts sharply with Little Flower’s quest for self-made dignity.

Eventually, Little Flower and Noble begin a secret relationship. When Miss Prudence, his betrothed, pleads with Little Flower to let him go, she refuses.

Despite the danger, she refuses to live as a hidden mistress. Linjing, consumed by jealousy and despair, falsely accuses her of being a fox spirit.

This leads to a humiliating trial where Little Flower’s feet are forcibly unbound in front of a crowd, exposing the violent traditions that still govern women’s bodies.

When her relationship with Noble is discovered, Little Flower is condemned by the sisterhood. Despite Noble’s promises, he fails to publicly defend her, and she is sentenced to death by pig cage drowning—a brutal punishment for women accused of dishonor.

In a rare moment of redemption, Linjing realizes the gravity of her betrayal. She pleads with Noble, threatening to kill herself if Little Flower is not saved.

At the final moment, Noble rescues Little Flower from execution, denouncing his inheritance and declaring his love publicly. Linjing stands beside him, risking her life in protest against injustice.

The moment marks both women’s transformation.

In the epilogue, Linjing writes to Little Flower from Shanghai, where she now teaches orphaned girls. Little Flower lives in modest happiness with Noble in Hong Kong, their lives built on mutual respect rather than social expectation.

Though their paths diverged, both women have reclaimed their agency and envision a world where women can define themselves outside the roles imposed upon them. Their stories, once marked by servitude and rivalry, now echo with resilience and hard-won hope.

Characters

Little Flower

Little Flower is the emotional and moral anchor of The Lotus Shoes, a character whose arc transforms from a voiceless child to a woman with agency and dignity. Sold into servitude at six years old by her mother, Aa Noeng, Little Flower’s story is steeped in betrayal, abandonment, and a slow awakening to her own self-worth.

The trauma of foot-binding—inflicted as a means of social advancement—sets the tone for her early life: a girl made to believe pain is love and obedience is virtue. Yet, through this imposed silence, she quietly resists.

Her embroidery becomes not only a skill but a symbolic act of self-expression and quiet rebellion, asserting her value beyond the shackles of servitude. Her relationship with Linjing evolves from one of dominance and subordination to a fraught sisterhood defined by competition, jealousy, and moments of tenderness.

As she matures, Little Flower learns to navigate complex hierarchies, both in the Fong household and later in the silk factory. Her resilience is tested repeatedly—through the loss of her hopes for marriage, betrayal by those she trusted, and the brutal unbinding of her feet in a public spectacle of shame.

But she reclaims her narrative when she refuses Noble Siu Je’s offer to live as his mistress, recognizing that her dignity cannot be contingent on another’s conditional affection. In the end, her decision to choose herself, even when it nearly costs her life, solidifies her as a character of immense strength.

From the ashes of societal cruelty, she forges a life of love, labor, and quiet defiance, eventually living in Hong Kong with a partner who values her not for what she suffered, but for who she is.

Linjing

Linjing is perhaps the most complex and tragic character in The Lotus Shoes, born into privilege yet perpetually denied control over her own fate. As Little Flower’s young mistress, she is initially portrayed as spoiled, jealous, and cruel—embittered by the affection Little Flower receives and frustrated by her own lack of talent, particularly in embroidery.

Linjing’s resentment is amplified by her colorblindness, a secret that humiliates her in front of her American tutor, Miss Hart. Though she projects cruelty, her actions are often desperate attempts to assert control in a world where her worth is dictated by the expectations of her conservative family and the shifting tides of modernization.

Her shame over her unbound feet, imposed by her father’s progressive politics, places her at odds with her grandmother Maa Maa and undermines her sense of belonging.

Linjing’s descent into disgrace following her mother’s suicide forces her into the same servitude she once oversaw. In the silk factory, stripped of all status, she becomes reliant on Little Flower, unable to reconcile the shift in their dynamic.

Her emotional breakdowns, delusions about marrying Noble Siu Je, and final act of betrayal—accusing Little Flower of being a fox spirit—are manifestations of her fear, pride, and internalized hierarchy. And yet, her character is not irredeemable.

She ultimately risks her life to save Little Flower from execution, a profound act of atonement that speaks to her growth. By the end, Linjing is a woman transformed—teaching orphaned girls in Shanghai, writing letters of apology and reflection, and finally grasping the meaning of strength not as dominance, but as accountability and compassion.

Aa Noeng (Phoenix)

Aa Noeng, Little Flower’s mother, is a character shaped by sorrow, poverty, and the brutal choices of survival. Her decision to sell her daughter into servitude is portrayed not as an act of cruelty, but one of profound despair—a twisted expression of maternal love in a world with few options for impoverished widows.

She prepares Little Flower for a life of service under the guise of adventure and love, beginning the foot-binding process to secure her daughter’s “future,” all the while knowing she is delivering her into bondage. Her emotional breakdown during the sale, though private, reveals the deep schism between her duty as a mother and her powerlessness as a woman in a patriarchal society.

In her later incarnation as Phoenix, the disgraced concubine of the Fong family, she suffers again for the sins of others. Her final act—taking hemlock to save Linjing from public disgrace and a remote nunnery—is both tragic and noble.

The letter she leaves behind speaks to a woman who lived her life within the confines of submission, but who tried to carve out small spaces of protection for those she loved. Aa Noeng is a haunting figure, a reminder that survival often comes at the cost of motherhood, and that love in oppressive systems can be as destructive as it is redemptive.

Spring Rain

Spring Rain is Little Flower’s companion in bondage and a reflection of a more overt resistance to servitude. She is bold, wounded, and unafraid to confront the ugly truths that Little Flower often internalizes.

Unlike her friend, she refuses to romanticize escape through marriage or artistic expression. Having suffered under the abusive hand of Second Fong taai taai, Spring Rain views the world with clear-eyed pragmatism, placing her hopes in flight rather than transformation.

Her plan to escape with an opera troupe during a banquet illustrates her courage and her desperation. When she lashes out at Little Flower—accusing her of privilege—it reveals the divisions even among the oppressed, shaped by proximity to power and visibility.

Yet, their friendship survives these fissures. Spring Rain’s journey is marked by mistrust of foreigners, especially Miss Hart, whom she holds responsible for her father’s ruin via opium.

Still, she allows Little Flower to assist her, trusting her friend’s loyalty even as she remains skeptical of the systems that govern their lives. Her eventual escape, aided by the Christian underground, is a triumph not only of her will but of her ability to trust selectively.

Spring Rain is a vivid portrait of survival through refusal, anger, and the unyielding pursuit of freedom on her own terms.

Noble Siu Je

Noble Siu Je is a complicated emblem of patriarchal benevolence in The Lotus Shoes—a man who wants to do right but is trapped by the same social systems he benefits from. As a factory owner, he appears progressive, respectful to the women in his care, and appreciative of art and hard work.

His early compassion toward Linjing and recognition of Little Flower’s embroidery talent suggest a man willing to look beyond social hierarchy. Yet, when the moment of truth arrives—when Little Flower is accused, endangered, and humiliated—he hesitates.

His reluctance to defy his family and claim Little Flower publicly reveals the limits of his progressive ideals.

Eventually, pushed by Linjing’s intervention and his own love for Little Flower, he does act—arriving at the riverbank, saving her life, and renouncing his inheritance. This act redeems him somewhat, though it also underscores how deeply entrenched societal constraints are, even for men with power.

Noble Siu Je is not a savior, nor is he a villain. He is a nuanced character whose journey from passive sympathizer to active partner highlights the cost of true allyship in a rigidly stratified world.

Miss Hart

Miss Hart represents the well-meaning but complicated presence of Western influence in Qing dynasty China. As an American tutor who advocates for Christian abolitionist values, she is a beacon of hope for some, especially Little Flower, whom she encourages and empowers through education and embroidery.

Her recognition of Little Flower’s talents and her willingness to aid Spring Rain’s escape show her commitment to justice. However, she is also viewed with suspicion, particularly by Spring Rain, who blames Westerners for colonial damage and familial loss.

Miss Hart’s role is pivotal in providing a counter-narrative to the dominant cultural systems of oppression. She champions female education and dignity, subtly undermining the Fong family’s rigid expectations.

While she never oversteps or imposes her worldview with violence, her presence is a reminder of both the promise and the peril of Western intervention. Through her, The Lotus Shoes navigates the delicate balance between allyship and cultural intrusion, showing that even acts of goodness are never free of historical weight.

Themes

Female Bondage and the Illusion of Escape

In The Lotus Shoes, the construct of female bondage is not simply explored through visible chains or servitude but also through cultural norms, traditions, and deeply embedded systems of patriarchy that define a woman’s value in terms of her utility, appearance, and obedience. From the opening scene, Little Flower is thrust into a life of literal and symbolic bondage—her role as a muizai strips her of familial protection and childhood, while the agonizing process of foot-binding, sold as a gesture of love, enforces the lie that pain equals worth.

The story reveals how foot-binding becomes a metaphor for the suppression of female autonomy, and how even maternal affection is filtered through a survivalist logic that condones subjugation.

Little Flower’s journey through the Fong household, the Celibate Sisterhood, and ultimately into her own sense of agency illustrates the layered nature of bondage. Physical freedom—symbolized by the potential to marry—is constantly dangled as a carrot, yet remains inaccessible without significant sacrifice.

Even in moments where autonomy appears possible, such as Little Flower’s talent in embroidery or Spring Rain’s planned escape, the threat of systemic punishment looms large. These women remain bound by an economic and cultural machine that assigns their futures to men, whether through fathers, husbands, or patrons.

What becomes evident is that escape is rarely clean. It demands compromise, risk, and often the betrayal of other women.

Yet the novel complicates this by also showing that the promise of male protection—whether through marriage to Noble Siu Je or the Christian networks offered by Miss Hart—is fraught with its own hierarchies. Even when freedom is attained, as in the final chapters, it is not through the promised systems of deliverance, but rather through radical self-respect and solidarity among women, reshaping the illusion of escape into a hard-won reclamation of dignity.

Female Solidarity and the Complexity of Sisterhood

The relationships between women in The Lotus Shoes are characterized by deep emotional entanglements, shifting power dynamics, and moments of both brutal competition and tender alliance. Little Flower’s bond with Spring Rain is grounded in shared suffering, their servitude forming the backdrop for a friendship that transcends blood ties.

This sisterhood is neither idyllic nor unbreakable—Spring Rain’s resentment over Little Flower’s perceived favoritism and privilege leads to a moment of bitter confrontation. Yet the narrative insists on the endurance of their commitment to each other, especially as Little Flower pledges to help Spring Rain escape, a profound act of mutual sacrifice.

This theme continues through the fraught connection between Little Flower and Linjing, a relationship marked by servitude, envy, and eventual transformation. Linjing, shaped by entitlement and constrained by her own social pressures, lashes out in ways that are cruel and manipulative.

However, her actions are never portrayed as purely villainous. They are symptoms of a system that teaches women to police one another, to view kindness and competence in others as threats rather than resources.

Her false accusation of Little Flower as a fox spirit is one of the story’s most devastating betrayals, yet her later intervention to save Little Flower from execution illustrates that even within betrayal, remorse and redemption are possible.

Ultimately, the story refuses to flatten these dynamics into simple binaries. Female solidarity in this world is hard-won, fragile, and constantly undermined by the external pressures of survival.

Yet it is also the only force that consistently leads to salvation. Whether it is Miss Hart advocating for Little Flower’s talents, or Linjing risking everything to save her, these acts underscore the idea that genuine sisterhood emerges not from sameness or even shared beliefs, but from the courage to act justly when it matters most.

Class Stratification and Social Mobility

Class is a relentless force in The Lotus Shoes, shaping every character’s choices, identities, and ultimate fates. From the outset, Little Flower’s worth is determined not by her intelligence or spirit, but by the circumstances of her birth and the size of her feet.

Sold into servitude by a desperate mother, she occupies the lowest rung of the social order—property without autonomy. Her journey reflects the impossibility of mobility for someone marked by both poverty and gender.

Her embroidery, though exquisite, is not enough to overcome the stigma of her unbound feet or lowly origins. Even as she attempts to prove her value through skill and diligence, the narrative reminds us that merit in this world is only recognized when it aligns with class expectations.

Linjing’s arc provides a counterpoint. Born into wealth and privilege, she initially enjoys the protection of status.

But when her family falls into disgrace and she is exiled to the Celibate Sisterhood, her status evaporates, and she is forced to confront the world from the vantage point of labor and hardship. Her refusal to adjust to this new reality underscores how deeply class consciousness is internalized.

Unlike Little Flower, whose strength lies in adaptation and resourcefulness, Linjing struggles to redefine herself without the privileges she once took for granted.

The story ultimately critiques the myth of upward mobility. Even when Noble Siu Je offers affection and promises, he cannot fully reconcile Little Flower’s background with the public expectations of his class.

True mobility, then, only comes through sacrifice and rupture. When Noble renounces his inheritance, it is not an endorsement of equality, but an acknowledgment that love and dignity demand an entirely new framework—one that rejects the class structures that made their union taboo in the first place.

Gender, Power, and Bodily Autonomy

The female body is a site of control, punishment, and resistance in The Lotus Shoes. Foot-binding is perhaps the most graphic expression of this theme—an act performed under the guise of love and tradition, but in truth a brutal assertion of male desirability and social conformity.

Little Flower’s bound feet become both her hope and her curse, a symbol of her desire for escape through marriage and a visible mark of her subjugation. When they are forcibly unbound in a public spectacle, it is both a humiliation and a symbolic stripping of her claim to femininity and respectability.

Throughout the narrative, the loss of bodily autonomy haunts nearly every woman. Spring Rain’s body is subjected to violence and coercion, leading her to seek escape through dangerous means.

Linjing’s body becomes a vessel of inheritance and social transaction, particularly when her father arranges a marriage to a progressive ally without her consent. Even noble women like Madam Phoenix face bodily judgment, culminating in her self-inflicted death as the only means of retaining agency over her fate.

The climax of the narrative—Little Flower’s punishment by pig cage drowning—reveals the grotesque lengths to which society will go to control female sexuality and enforce compliance. Accused of seduction and moral corruption, she is subjected to ritualized violence meant to cleanse and punish.

That she survives this ordeal, and that Noble ultimately claims her publicly, does not erase the trauma but reframes her body as her own. Her survival is not about romantic vindication, but about rejecting a culture that sees the female body as either asset or shame.

In reclaiming her dignity, Little Flower asserts that her worth lies not in compliance or sacrifice, but in self-ownership.

The Intersection of Colonialism and Resistance

Set in the twilight of Qing dynasty China, The Lotus Shoes subtly but powerfully examines the impact of Western colonialism on Chinese society, particularly through its influence on class, religion, and the role of women. Characters like Miss Hart, the American tutor who espouses abolitionist and Christian ideals, embody the well-meaning but intrusive nature of colonial interventions.

Her efforts to educate, liberate, and reform are framed as progressive, yet not universally embraced. Spring Rain, for example, regards her with deep mistrust, citing the opium crisis and Western encroachment as reasons for skepticism.

The conflicting responses to Miss Hart highlight a community fractured by foreign influence—some see hope, others see erasure.

The story also uses religion and philanthropy as instruments of both control and resistance. The Christian networks that assist in potential escapes are portrayed as lifelines, but also as agents of cultural displacement.

Even the Celibate Sisterhood, though rooted in Chinese tradition, mirrors monastic discipline associated with Westernized institutional care. Within this context, characters like Little Flower must navigate not just the oppression of patriarchy, but the layered pressures of a society negotiating its identity under the shadow of foreign dominance.

Importantly, the narrative resists simple binaries. Miss Hart is not a savior, but neither is she a villain.

Her role becomes a lens through which the complexities of cross-cultural solidarity and power are examined. By choosing to accept help from Miss Hart while also preserving her cultural identity and autonomy, Little Flower carves out a resistance that is neither fully assimilationist nor entirely nationalist.

Her survival strategy is one of balance, asserting that liberation can draw from many sources without surrendering selfhood.