The Magician of Tiger Castle Summary, Characters and Themes

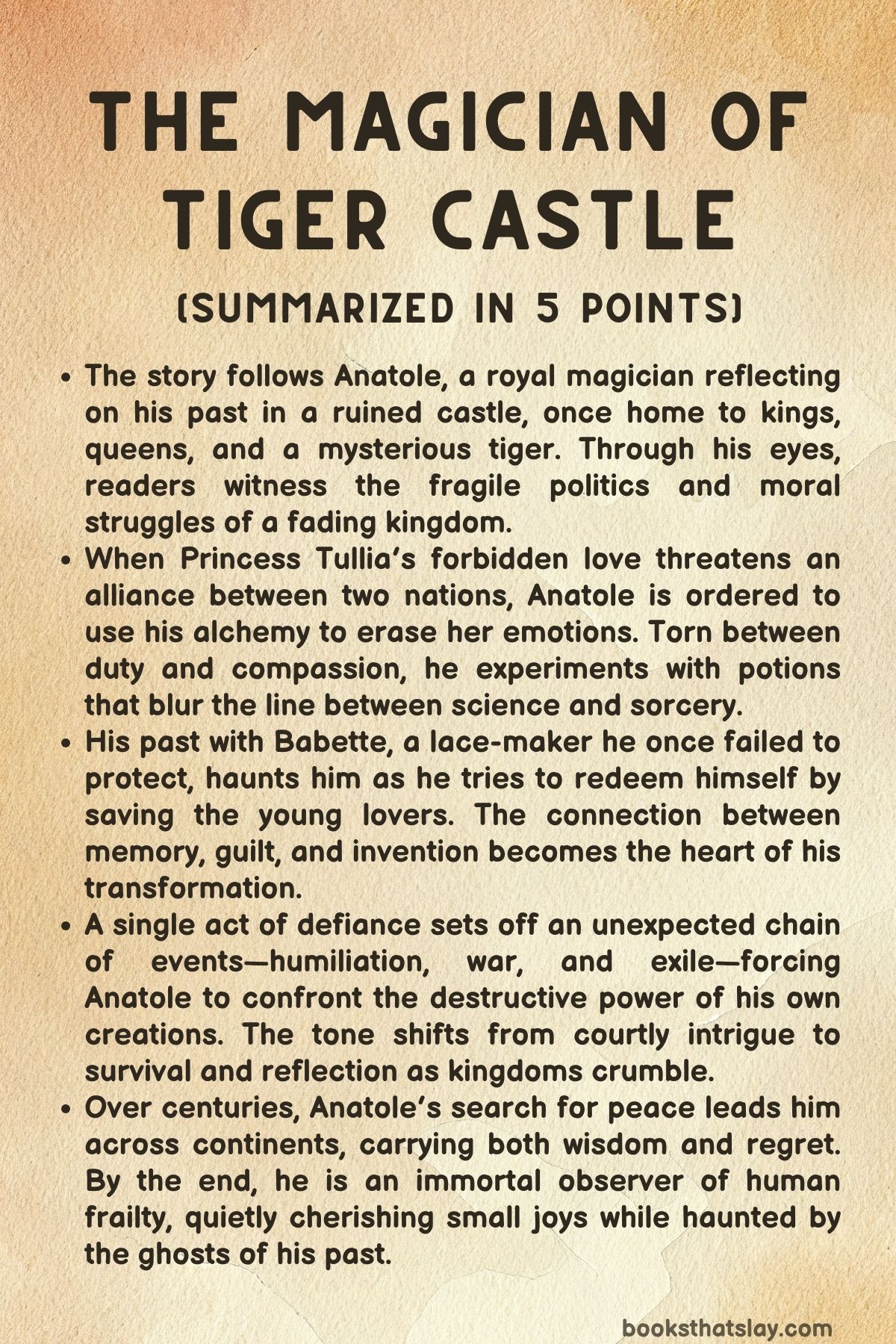

The Magician of Tiger Castle by Louis Sachar is a richly imagined historical fantasy that explores love, memory, and moral consequence through the life of Anatole, a royal magician in a fading medieval kingdom. Told through the recollections of an aged narrator who claims to be Anatole himself, the story blends court intrigue, alchemy, and emotional reflection into a tale about the costs of knowledge and the fragile boundary between science and sorcery.

As Anatole’s experiments with potions shape the destinies of those around him, including a doomed princess and a naïve young lover, his pursuit of mastery becomes both his gift and his curse.

Summary

An elderly man sits in a quiet European village near the ruins of Tiger Castle, sipping coffee and thinking about his bruised hands. Tourists see only a relic of the past, but he sees memories.

Once, he was Anatole—the court magician of Esquaveta—who lived five centuries earlier. When a tour guide tells of kings and princesses but omits Anatole’s name, the old man feels both invisible and immortal.

He recalls the moment everything began: the arrival of a tiger that forever changed his kingdom’s fate.

In the year 1523, Esquaveta was a minor kingdom facing economic ruin. King Sandro and Queen Corinna prepared to ally with the powerful Oxatania through the arranged marriage of their daughter, Princess Tullia, to Prince Dalrympl.

As part of the negotiations, Oxatania sent a tiger as a wedding gift. The beast’s arrival captivated the court—beautiful, dangerous, and incomprehensible.

While nobles argued over how to return such a gesture, Anatole was tasked with a hopeless assignment: to turn black Icelandic sand into gold to refill the treasury. His experiments failed, eroding his standing at court.

Meanwhile, the royal regent Dittierri proposed a glass elephant as a suitable return gift for Oxatania. But before the grand wedding could proceed, disaster struck.

Princess Tullia, now a young woman with striking mismatched eyes, refused to marry Dalrympl. She had fallen in love with a humble apprentice scribe named Pito.

The scandal threatened the alliance, and Anatole was ordered to intervene—not as a scientist, but as a manipulator of hearts.

Anatole visited Tullia, finding her distraught and restrained by her maid. When freed, she confessed her love for Pito, explaining that their intimacy had been intellectual rather than physical—they had shared books, not beds.

Still, she pleaded with Anatole to save the young man from execution. He collected her tears for a potion and promised to find a way.

But instead of helping, Queen Corinna commanded him to administer opium to dull the princess’s defiance. The king added a crueler command: Pito was to be executed before Tullia’s eyes at her own wedding feast.

Desperate, Anatole devised an alternative—a potion to erase Tullia’s memories of Pito altogether. He was permitted to test it on the prisoner.

Deep in the castle dungeon, Anatole met Pito, who awaited death with calm resignation. Through their talks, the magician realized the young man’s love was pure and selfless.

When a tear slid down Pito’s cheek, Anatole captured it. It would become the potion’s key ingredient.

In his workshop, Anatole prepared his most ambitious brew, blending Tullia’s and Pito’s tears with herbs and minerals, believing emotions could be transformed into alchemical elements. When the potion was ready, he tricked Pito into drinking it, pretending it would save the princess.

The two spoke about love and regret, and Anatole revealed his own lost romance with Babette, a lace-maker he had once loved but failed to protect. As he remembered her, he realized his craft was driven less by magic than by remorse.

Over the following days, Anatole refined his experiments. Each mixture produced strange effects on Pito: some heightened emotions, others erased them.

Tullia visited him secretly, threatening to end her life after the execution. To calm her, Anatole promised he had a plan.

In truth, he was uncertain whether memory could truly be erased—or only rewritten.

The day came when he was ordered to abandon his potions and prepare “poppy tears” for Tullia’s obedience. Outwardly obedient, he substituted harmless tea for the drug, then brewed a final memory potion identical to Pito’s.

Tullia drank it willingly, believing it was meant to free her beloved. Soon after, Anatole was accused of treason but narrowly spared when King Sandro declared him a hero—Tullia, after all, no longer remembered Pito.

Anatole’s victory brought him honor and guilt in equal measure.

During the royal banquet, Anatole sat among nobles as Tullia, radiant and smiling, entered with her new husband. When Anatole saw the groom’s face, he froze—it was Dalrympl, the same nobleman who had once assaulted Babette.

Realizing his creation had allowed cruelty to triumph twice, Anatole felt only emptiness.

Soon after, Dalrympl developed a grotesque rash on his face. Anatole was summoned to treat him and used the opportunity to mock the prince subtly.

His concoction cured the symptoms but left Dalrympl’s voice permanently childish. During the wedding ceremony, his falsetto provoked laughter, leading to chaos, riots, and war between Esquaveta and Oxatania.

Anatole’s prank had unleashed devastation.

As cities burned and corpses filled the cathedral, Anatole staggered through the carnage. Guilt replaced pride.

The magician who once sought truth through science was now the architect of ruin. Returning to Tiger Castle, he tended to the wounded, helped by Pito and a soldier named Carlo.

Peace seemed impossible. Then came orders for him to brew a potion that would make Tullia obedient to her new conqueror, Dalrympl, who demanded her as tribute and Anatole as a sacrifice to the tiger.

Tullia, now hardened by loss, pretended to agree but secretly plotted revenge.

Together, Anatole, Tullia, and Pito attempted to escape. Their plan collapsed when a maid discovered them, and Anatole was imprisoned.

The supposedly deaf jailer, Harwell, helped him flee through secret tunnels. The three fugitives emerged into the forest, disguising themselves as peasants.

They fought off bandits and debated philosophy and politics as they journeyed toward freedom, with Tullia dreaming of reaching a place called Utopia—an imagined land of equality. Their escape led them to the bustling port city of Torteluga, where they reunited with Mario Cuvio, an explorer and Anatole’s old friend.

He agreed to help them flee by sea if Pito could beat him at chess.

But fate intervened. Anatole was captured and taken back to Tiger Castle, accused of kidnapping and murder.

Queen Corinna treated him cordially, while the monstrous Dalrympl—now king—mocked him. The two shared a final drink laced with a potion granting unnatural longevity.

Dalrympl, deluded by ambition, consumed it eagerly. Anatole realized too late that the curse of living too long would be punishment enough.

Imprisoned again, Anatole survived for nearly a century in the castle’s depths. Empires rose and fell above him.

The tiger that once symbolized royal power perished long ago, its bones buried beneath rubble. When freedom finally came, Anatole wandered across the world, searching for traces of the past.

He sailed to the New World, met descendants of familiar souls, and found peace in solitude. Centuries later, he lives quietly by the Canadian shore, feeding crumbs of croissant to a tiny creature in his hoodie pocket—the only remnant of his strange alchemical life.

Thus ends the story of The Magician of Tiger Castle: the tale of a man who mastered potions but never conquered regret, whose pursuit of transformation left him unchanged, and whose centuries of life could not restore what memory—and love—had taken away.

Characters

Anatole

Anatole, the narrator and titular magician of The Magician of Tiger Castle, stands as one of Louis Sachar’s most complex and morally conflicted creations. Once the royal alchemist of Esquaveta, Anatole bridges the realms of science and sorcery, embodying the tension between intellect and emotion, reason and guilt.

His brilliance is matched only by his deep insecurities—his failed experiments with transmutation mirror his inability to transform his own regrets into peace. Haunted by the death of his beloved Babette and his cowardice in defending her, Anatole devotes his long life to the study of memory, grief, and redemption.

His potions, especially those made with tears, serve as metaphors for the human longing to control pain and loss. Yet, his manipulations of memory—whether erasing Tullia’s love or altering voices—reveal a tragic irony: in seeking to alleviate suffering, he perpetuates it.

As the story progresses across centuries, Anatole evolves from an ambitious court magician into a wandering philosopher, surviving through science but living under the weight of conscience. His final years, spent in solitude with his small creature companion, reflect both the immortality he once sought and the isolation that immortality inevitably brings.

Princess Tullia

Princess Tullia, daughter of King Sandro and Queen Corinna, is the embodiment of innocence, intellect, and rebellion against the cruel machinations of royal politics. From a curious child fascinated by Anatole’s experiments, she grows into a young woman torn between duty and love.

Her heterochromatic eyes—one blue, one green—symbolize her dual nature: the obedient princess and the passionate dreamer. Her love for Pito is not merely romantic but philosophical, rooted in shared readings of Utopia and discussions about freedom and equality.

Tullia’s refusal to marry Prince Dalrympl is both a personal act of defiance and a political tragedy, igniting the chain of events that lead to war and ruin. Even after Anatole erases her memories, her spirit persists, evident in her later resolve to confront and escape tyranny.

In the wilderness, she becomes hardened, pragmatic, and fiercely protective, wielding a knife as confidently as she once held a book. Tullia’s transformation from captive princess to fugitive visionary echoes the broader themes of the novel—how memory, love, and identity survive even when history attempts to erase them.

Pito

Pito, the young scribe whose love for Princess Tullia defies the social hierarchy of Esquaveta, is both an idealist and a symbol of uncorrupted humanity. His quiet intelligence and philosophical bent set him apart from the courtiers around him.

Initially portrayed as meek and resigned, Pito’s conversations with Anatole reveal a deep moral clarity. He speaks of love and mortality with a serenity that contrasts sharply with the desperation of those in power.

His relationship with Tullia, rooted in shared intellect rather than sensual passion, humanizes the otherwise cold political world of the castle. Pito’s imprisonment and eventual transformation through Anatole’s potions mark the intersection of science and soul—his memory is manipulated, his fate determined by others, yet he remains a figure of grace.

Later, as a fugitive, he becomes a protector and equal partner to Tullia and Anatole, demonstrating courage and compassion in adversity. Pito’s moral steadiness and philosophical resignation make him the quiet heart of the novel’s moral inquiry.

Queen Corinna

Queen Corinna of Esquaveta represents the seductive cruelty of power cloaked in beauty. She is both an architect of political strategy and an agent of emotional destruction.

Corinna’s intelligence is sharp, her composure unbreakable, and her ruthlessness chilling. Her order to dose her daughter with “poppy tears” exemplifies her belief that control—emotional, political, or psychological—is the only path to stability.

She stands in stark contrast to Anatole’s wavering conscience, embodying pure pragmatism devoid of compassion. Yet, Corinna’s character is not one-dimensional; her manipulation is born from fear of vulnerability in a collapsing kingdom.

Her eventual downfall, foreshadowed by the cut on her finger from the broken potion pot, symbolizes how even those who command alchemy cannot escape the poisons of their own making. Corinna’s reign, like her beauty, is both luminous and fatal, leaving behind the ruin of those she sought to preserve.

King Sandro

King Sandro is portrayed as a weary monarch struggling to maintain his crumbling kingdom amid financial ruin and political dependency. Beneath his bluster and occasional bursts of authority lies a man deeply insecure about his own power.

His reliance on Anatole’s alchemy to restore the treasury and his complicity in morally questionable schemes—such as erasing his daughter’s memory or executing her lover—reveal his moral decay. Sandro’s kingship is performative, sustained by spectacle and deceit rather than wisdom.

His approval of Anatole’s experiments, motivated by political convenience, transforms science into a tool of tyranny. Yet, in moments of candor, he hints at regret, as though aware that his reign, like his body, is rotting from within.

King Sandro’s legacy is one of failure masked by ritual—a tragic monarch undone not by enemies but by his inability to distinguish control from destruction.

Prince Dalrympl

Prince Dalrympl of Oxatania serves as the embodiment of arrogance and corruption within aristocratic privilege. Vain, cruel, and obsessed with his own image, Dalrympl’s character arc—from charming suitor to monstrous tyrant—is a portrait of unearned power.

His earlier assault on Babette exposes his predatory nature long before his political ambitions come to light. When Anatole’s potion alters his voice into a humiliating falsetto, it acts as poetic justice, reducing his grandeur to ridicule.

Yet, Dalrympl’s humiliation becomes the spark for catastrophic war, demonstrating how wounded pride can devastate nations. His later obsession with immortality through the “Oxatanian tea” completes his descent into grotesque hubris.

Dalrympl’s eventual death—killed by his own vanity in the tiger moat—serves as both cosmic retribution and a grim reminder that power without conscience consumes itself.

Dittierri

The regent Dittierri functions as the pragmatic bureaucrat of Esquaveta, a man caught between loyalty, ambition, and self-preservation. Though less malevolent than the queen, his moral flexibility makes him complicit in nearly every atrocity committed by the crown.

Dittierri’s fixation on appearances—his obsession with creating a glass elephant to rival Oxatania’s tiger—illustrates the absurdity of political theater. He is a man who values optics over ethics, decorum over decency.

Yet, his cynicism is tinged with melancholy; he understands the futility of his position but continues to play his part, unable to escape the machinery of royal corruption. Dittierri’s character underscores the theme that evil often thrives not through passion but through compliance and fear.

Babette

Babette, though appearing only in Anatole’s recollections, exerts a profound influence over his life and moral development. A humble lace-maker, she represents purity, creativity, and the dignity of the common class.

Her suffering at the hands of Dalrympl and Anatole’s failure to defend her form the emotional core of Anatole’s guilt. Through Babette, Louis Sachar explores how love can inspire both invention and ruin.

Her illness leads Anatole to discover the healing power of mold—an allegory for how beauty and decay coexist. Even after her death, Babette becomes Anatole’s moral compass, her memory the silent measure of his actions.

She is the lost ideal he spends centuries trying to resurrect through science, yet her absence remains the one mystery he can never solve.

Harwell

Harwell, the deaf jailer of Tiger Castle, is a deceptively simple character whose quiet presence conceals loyalty, cunning, and moral strength. Initially portrayed as a brute confined to shadows, he emerges as a subtle ally, aiding Anatole’s escape in a moment of peril.

His muteness and supposed deafness allow him to observe without interference, functioning almost as a guardian spirit within the castle’s underworld. Harwell’s compassion contrasts sharply with the cruelty of those above him; his rescue of Anatole becomes an act of redemption for the voiceless and oppressed.

Through Harwell, Sachar suggests that true humanity often survives in those society deems unimportant or inarticulate.

Mario Cuvio

Mario Cuvio, the drunken explorer and Anatole’s old friend, introduces levity and worldliness into the narrative’s later stages. A man of contradictions—brave yet cynical, coarse yet loyal—Cuvio embodies the adventurer’s spirit that Anatole has long abandoned.

His experiences in the wider world serve as a reminder of life’s vastness beyond the castle’s moral decay. Cuvio’s interactions with Tullia and Pito blend humor with wisdom, revealing that even the flawed can act as protectors.

Though his fate remains uncertain, his brief reappearance symbolizes freedom and renewal—the human capacity to begin again, no matter how corrupted one’s past.

Themes

Memory and Forgetting

In The Magician of Tiger Castle, memory functions as both a salvation and a curse. Anatole’s lifelong pursuit to manipulate memory through alchemy becomes the moral and emotional center of the story, symbolizing humanity’s struggle with guilt, loss, and the desire to rewrite the past.

His attempt to erase Princess Tullia’s love for Pito is not merely a scientific experiment—it is an echo of his own longing to undo his failure to save Babette, the woman he once loved. Through this act, memory transforms from a natural human faculty into a field of moral risk.

By erasing pain, Anatole also destroys meaning; by saving Tullia from grief, he erases her capacity to love. The novel interrogates whether suffering is an essential part of being human, and whether forgetting is an act of mercy or betrayal.

Over centuries, Anatole’s relationship with memory evolves from manipulation to reverence—he becomes a quiet observer of time, cherishing even his smallest recollections. The potion that first served as an alchemical instrument of power becomes, in retrospect, a metaphor for the fragility of identity.

When Tullia and Pito’s memories vanish, their love story becomes a casualty of political necessity, and Anatole’s triumph turns hollow. By the end, memory stands as a fragile but vital thread connecting past and present, truth and illusion, life and death.

It reveals that to live meaningfully is to remember—imperfectly, painfully, but fully.

Love and Moral Responsibility

The story places love in tension with duty, exploring how devotion can both redeem and destroy. Anatole’s compassion for Tullia and Pito emerges as the most human force in a world ruled by power and deceit.

His love for Babette drives his science, but also his guilt; it propels him to act mercifully toward Tullia but blinds him to the consequences of his choices. Love is not portrayed as a romantic ideal but as an ethical dilemma—an emotion that demands sacrifice and often brings ruin.

Tullia’s love for Pito challenges dynastic authority, revealing the cruelty of a political system where affection is expendable. Their relationship, innocent yet condemned, underscores how purity cannot survive within structures of control.

Anatole’s moral torment grows from his attempt to balance compassion with obedience, illustrating how even good intentions can become instruments of tragedy. His ultimate decision to free Tullia and Pito and flee into exile represents love’s evolution into selflessness, yet his centuries-long isolation reflects the price of moral compromise.

Love in The Magician of Tiger Castle is never static—it changes form, from desire to guilt, from pity to memory, from rebellion to redemption. It is the force that exposes both the grandeur and futility of the human heart.

Power, Corruption, and Obedience

Power in the novel is omnipresent, shaping every relationship and moral choice. The royal court of Esquaveta operates under fear, vanity, and the desperate need to appear strong to its rivals.

Kings, queens, and regents manipulate appearances while ignoring the suffering beneath their rule. Anatole’s experiments are driven not by scientific curiosity alone but by royal coercion—a reflection of how knowledge itself becomes corrupted by authority.

Queen Corinna’s cruelty, King Sandro’s political desperation, and Prince Dalrympl’s vanity form a chain of command that demands obedience and rewards deceit. The court’s obsession with symbols—the tiger, the glass elephant, the spectacle of the wedding—reveals a regime sustained by illusion.

Anatole’s role as magician is both literal and metaphorical: he is the servant of appearances, forced to conjure miracles to sustain a decaying order. Yet his defiance, though subtle, lies in using his intellect for subversion rather than compliance.

When his actions unintentionally spark war, the narrative exposes how fragile power truly is—built on fear, pride, and misunderstanding. Across centuries, Anatole learns that obedience to power erases humanity, while moral resistance carries its own form of nobility, even in defeat.

The story thus becomes a meditation on the corrosive nature of authority and the ethical peril of serving it.

Science, Faith, and the Limits of Knowledge

Anatole’s alchemical pursuits represent the intersection of reason and belief, science and superstition. He begins as a man of faith in knowledge, convinced that careful experimentation can bridge the gap between the material and the spiritual.

His potions, however, blur this boundary, forcing him to confront the ethical consequences of scientific ambition. Every success leads to catastrophe, suggesting that understanding nature’s secrets without moral grounding leads to ruin.

The narrative also contrasts the empirical precision of Anatole’s work with the irrationality of the world around him. His court praises miracles but punishes inquiry, demanding results that serve politics, not truth.

The irony is that Anatole, in seeking to purify knowledge, creates deception—his memory potion alters not only minds but destinies. Over time, his experiments transform into reflections on mortality and meaning, echoing the Enlightenment tension between human reason and divine mystery.

By the story’s end, his science has turned into contemplation; he no longer seeks to change the world but to understand it quietly. In The Magician of Tiger Castle, knowledge is not celebrated as power but questioned as temptation, a double-edged force that can illuminate or destroy depending on the hand that wields it.

Guilt, Redemption, and the Passage of Time

Time in the novel moves like an ocean, eroding guilt but never fully cleansing it. Anatole’s centuries-long life serves as an allegory for the burden of remorse—the weight of living beyond one’s mistakes.

His initial guilt over Babette’s death transforms into an existential reflection on the cost of inaction and the illusion of control. Through his endless years, he witnesses the consequences of choices made in haste: the wars, deaths, and lost loves that spring from a single potion.

Redemption becomes less about forgiveness than about endurance—continuing to live, to serve, to remember. His healing of the wounded after the war and his care for his small creature in old age represent quiet acts of atonement.

The passage of time strips him of ambition, leaving only a desire for peace and understanding. By the final scenes, where Anatole tends his gardens and feeds crumbs to his tiny companion, time itself becomes redemptive.

The castle’s ruins and the tiger’s absence symbolize both decay and renewal, suggesting that even the most tragic lives can find meaning in persistence. Through Anatole’s journey, The Magician of Tiger Castle asserts that redemption does not erase guilt—it transforms it into wisdom, teaching that survival, when coupled with compassion, is its own form of grace.