The Maiden and Her Monster Summary, Characters and Themes

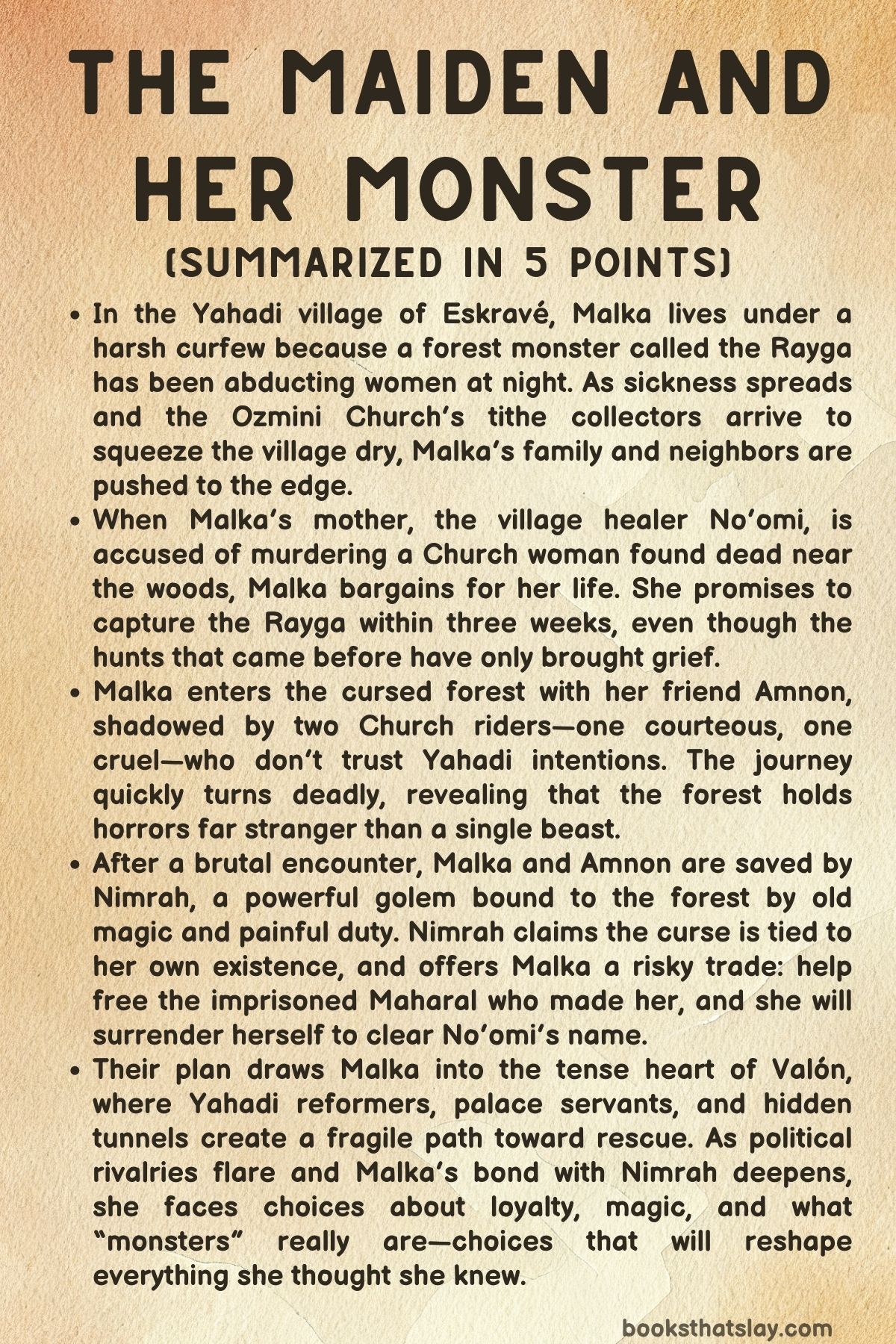

The Maiden and Her Monster by Maddie Martinez is a dark fantasy set in a village living under fear, faith, and occupation. In Eskravé, a cursed forest and the creature called the Rayga have taken women for years, while an oppressive Church exploits the villagers’ terror.

Malka, a healer’s daughter, is forced into an impossible bargain when her mother is accused of murder. To save her, Malka enters the corrupted woods with uneasy allies and finds that the truth behind the monster is stranger than any village story. The novel mixes folklore, politics, and moral choice, following Malka as she learns what power costs and who gets to decide what is holy.

Summary

Eskravé is a Yahadi village pressed against Mavetéh, a once-living forest now warped into rot and silence. Every night the villagers obey curfew, because the Rayga—an unseen creature—has been dragging girls and women into the trees.

Malka lives there with her mother No’omi, a village healer everyone calls Imma, her father Abba, and her sisters Danya and Hadar. On the anniversary of Malka’s best friend Chaia’s disappearance, the family lights a mourning candle.

The grief is routine now, as are the men’s drunken hunts that return with nothing but injuries and shame. Imma depends on a rare herb, black perphona, to treat a wasting sickness spreading through the village, especially among the hunters, but their supply is nearly gone.

The village’s terror is made worse by the arrival of the Order of the Paja, Ozmini Church tithe collectors. Led by Father Brożek, they demand more grain and goods than Eskravé can spare.

When the metalsmith Minton protests that poverty comes from the curse and missing workers, Brożek orders him punished. A knight chops off Minton’s hand in front of everyone.

Malka, sick with horror, realizes that the Church is as dangerous as the forest. The Paja set up camp and begin feeding themselves from Yahadi stores, raiding homes, and showing open contempt.

Malka spends her mornings delivering Imma’s tonics to the sick. Her friend Amnon, a fisher’s son, helps her and shares her anger at Church cruelty.

A Paja knight named Václav harasses Sid the baker’s daughter; Amnon confronts him and is beaten, then forced to provide fish for the knight’s table. The humiliation spreads through the village like another disease.

As weeks pass, the tithe drains Eskravé toward starvation. Minton’s wound festers, men grow weaker, and Malka feels helpless.

She meets several Paja members away from the square: Aleksi, his younger brother Bori, and a woman named Rzepka. They treat her with a friendliness that feels dangerous in its novelty.

Rzepka, protected by her Ozmini faith, laughs off Malka’s warnings about nightfall and the Rayga. Malka runs home frightened, sensing how little the outsiders understand the woods or the village’s pain.

Soon after, Imma disappears at dawn, likely gone to gather black perphona in Mavetéh despite the risk. Malka follows Paja riders into the forest and finds a clearing where Rzepka lies dead, torn apart.

Imma’s hands are bloody from trying to help. Brożek seizes this chance to accuse Imma of witchcraft and sacrifice.

Malka tries to defend her, but the Paja drag Imma away to Valón for execution. In desperation, Malka offers a bargain: she will capture the Rayga and bring it as proof that the monster killed Rzepka.

Brożek grants her three weeks, until the Léčrey eve, promising to kill Imma if Malka fails. Amnon insists on joining the hunt.

Malka resents his insistence but accepts, knowing she cannot survive alone and Eskravé may not survive without Imma.

At the forest edge they are joined by Aleksi and Václav, ordered to watch Malka for deception. The four enter Mavetéh.

Inside, the place feels sick and wrong: twisted trunks, dead air, and the smell of decay. They find fresh corpses half-swallowed by the earth—women and an Ozmini man—ripped apart.

Malka can’t find Chaia among them, and the search sharpens her fear into resolve. They camp at night.

Aleksi debates whether the Rayga is real, offering Church legends and doubts; Malka senses he is less cruel than most Paja, yet still chained to their worldview. Near the river, Malka is attacked by a tree that comes alive, lifting and crushing her.

The Rayga emerges from the bark, sap-slick and clawed. Aleksi tries to fight; the creature nearly kills him.

Václav finishes Aleksi to “spare” him, then turns his rage on Malka and Amnon, blaming them for the attack. Malka knocks Václav into the rocks, killing him, but a branch throws her into the river.

She sinks into freezing dark—then a hand pulls her out.

Malka wakes in a hut beside a towering figure made of stone and vine. The woman introduces herself as Nimrah.

She heals Malka quickly with tea and grim calm. Amnon is alive too; Nimrah carried them both away and fought the Rayga bare-handed.

Nimrah reveals she is a golem created by the Maharal of Valón to protect Yahad, but she was rooted to the Great Oak in Mavetéh five years earlier and cannot leave its reach. She says the Rayga is not a single beast: multiple monsters exist, made through Kefesh, the same force that animates her.

Worse, she admits the rooting bound her life-source to the forest, and the monsters began appearing because of that binding. Malka realizes Nimrah is what the village has been calling the Rayga.

Nimrah proposes a way out. If Malka and Amnon alter the rooting letters, Nimrah can be unrooted and re-bound to a portable life source—one of them.

In return, Nimrah will go to Brożek, surrender as the monster, and free Imma. She also wants help rescuing the Maharal, who has been imprisoned by the Church.

Amnon offers to take the rooting burden himself, and asks Malka to consider marrying him afterward. Malka cannot promise anything but accepts the plan, believing it is the only path to her mother’s survival.

Guided by Eliška, they obtain an old palace chapel map. They travel to Valón and visit Chaia’s home, where Malka is stunned to find Chaia alive; she had been taken into palace service after surviving sickness.

Chaia and her betrothed Vilém quickly join the rescue. Chaia smuggles Malka into the New Royal Palace disguised as a scullery maid, while Nimrah enters through the library in disguise.

In the palace Malka overhears Prince Evžen and Archbishop Sévren discussing tightening rule over Yahad. She reaches the chapel, finds Nimrah, and together they discover a tunnel behind a confessional.

They fight through guards to the dungeons and find the Maharal starved and mutilated, his hands cut off. Nimrah carries him out while Malka delays pursuit, but Malka’s Kefesh falters from the rooting sickness.

She is captured and brought to Sévren and Evžen. Sévren forces her to watch a brutal execution to terrify the city.

Before he can turn Malka into proof of Yahadi “treason,” Nimrah appears publicly with the Maharal’s letter demanding a restored trial. Sévren cannot refuse without exposing his abuses, and Malka is released.

During Léčrey celebrations, Nimrah vanishes. Malka has severed their bond, but still expects Nimrah to kill Sévren and fulfill the bargain.

Instead, Nimrah murders Prince Evžen onstage, sending the square into panic and unleashing a mob against Yahad. Malka realizes Nimrah is being controlled; the command inscription carved into her body can be used by anyone who knows the letters.

Malka and other conspirators suspect Sévren has taken control to spark violence and justify a crackdown. Malka climbs the clocktower and finds Sévren there with Nimrah.

Sévren admits he ordered the prince’s death to create a martyr and destroy Yahadi influence. He commands Nimrah to kill Malka.

Nimrah fights herself from within, begging Malka to end her rather than be forced to murder. Malka refuses to destroy her.

She scratches away the first letter of “emet” on Nimrah’s forehead, turning it into “met” and placing Nimrah into lifeless sleep instead of death.

With Nimrah down, Malka confronts Sévren. His stolen Kefesh is unstable and killing him.

In the struggle, his wild magic sends a rock toward Chaia; Vilém steps in front of it and dies. Sévren tries to kill Malka again, but loses his footing and is crushed inside the clocktower gears.

The mob collapses without its architect. Imma is found alive and freed amid the confusion.

Malka restores the missing letter on Nimrah’s forehead, waking her. They reunite, changed by what they have survived.

The Maharal later reveals the deeper origin of Mavetéh: Sévren once stole golem-making prayers, resurrected an Ozmini bride into a twisted golem, and the Maharal transformed her into the Great Oak, whose poisonous fruit and creatures cursed the forest. Only the creator can end life made by Kefesh without paying with another’s life, so the Maharal chooses to sacrifice himself, destroying the Great Oak and dying to lift the curse.

The forest calms, sickness fades, and Eskravé can heal.

After grief and reconciliation, Malka and Nimrah admit their feelings and begin a relationship built on trust rather than command. Months later, Duke Sigmund replaces King Valski, Yahad gain more protection, and the city starts to rebuild.

Imma remains in Valón to treat survivors, while Malka and Danya return to repair Eskravé. Nimrah travels to safeguard Yahadi communities and continue the work Vilém and the Maharal began.

Malka uses Kefesh for renewal instead of fear, holding her family and future close as they step into a fragile hope.

Characters

Malka

Malka is the emotional and moral center of The Maiden and Her Monster. As the eldest daughter in Eskravé, she carries a heavy, almost reflexive sense of responsibility for her family and community, which shapes nearly every decision she makes.

Her arc is defined by a steady widening of her world: she begins as a village healer’s helper fearful of the woods and the Church, and becomes someone willing to bargain with monsters, infiltrate palaces, and wield forbidden magic. Malka’s courage is not reckless bravado; it is a stubborn, grief-driven refusal to let the people she loves be taken from her.

That grief is longstanding and layered—Chaia’s disappearance, the women lost to Mavetéh, the daily decay caused by sickness and oppression—and it gives Malka both empathy and a volatile edge. She recoils from violence yet repeatedly faces it, revealing a psyche that doesn’t harden so much as learn to function while wounded.

Her relationship with Kefesh marks a second internal conflict: she fears what magic represents in the eyes of Ozmins and even within herself, but she also aches for the agency it offers, especially when ordinary means fail. By the end, Malka has not become a flawless hero; she remains someone who doubts, mourns, and feels torn between duty and desire.

What changes is her acceptance that survival and love may require claiming power on her own terms, not merely enduring what others impose.

No’omi (Imma)

No’omi is a quiet pillar of endurance and care, embodying the Yahadi tradition of healing and community responsibility. She is introduced through her work—brewing tonics, tracking herbs, tending the sick—and that labor is not incidental but fundamental to who she is.

Imma’s compassion is practical rather than sentimental, and she understands the village’s suffering in a way that blends medicine with social awareness; she sees clearly how the Rayga hunts, the Church tithes, and men’s despair feed into one another. Her trip into Mavetéh to gather black perphona shows both bravery and fatalistic duty: she risks herself because others will die if she doesn’t.

When the Paja accuse her of sacrifice and witchcraft, Imma becomes a symbol of Yahadi vulnerability under Ozmini rule, but she is never reduced to a helpless victim. Even while dragged away, her presence drives Malka into action and becomes the ethical compass for Malka’s mission—this is not only a hunt for a monster but a fight against a worldview that criminalizes Yahadi survival.

After her rescue, Imma’s arc moves into reconciliation and healing, not just of bodies but of family wounds, especially between her and Malka. She represents what the story ultimately protects: the continuity of care, memory, and home.

Abba

Abba is one of the book’s most painful portraits of how fear and powerlessness can curdle into cruelty. He is a man living beneath the twin pressures of the cursed forest and the Church’s domination, and his repeated, drunken “Rayga hunts” are less heroic efforts than rituals of desperation meant to reclaim dignity.

Yet he fails to transform that desperation into protectiveness; instead, it spills into domestic violence and emotional neglect, especially toward Danya. His arguments with Imma about herbs and medicine show how he resents what he cannot provide and distrusts what he cannot control.

Abba is not depicted as a monster equivalent to the Rayga, but he is part of the ecosystem of harm the curse produces—proof that the village’s danger is not only outside at night but inside homes shaped by trauma, patriarchy, and hopelessness. Even so, his character functions more as a tragedy than a caricature: a father who might have been different in another world, but who in this one becomes a threat to his daughters.

The story does not ask the reader to forgive him easily; it uses him to show how curses make victims who then victimize others.

Danya

Danya stands as Malka’s mirror and counterpoint: another eldest-adjacent daughter forced into premature adulthood, but one who has learned to survive through endurance rather than confrontation. At eighteen, she is already carrying bruises that are physical and psychic, especially from Abba’s abuse.

Her silence is not weakness but a survival strategy; she has adapted to fear by minimizing herself, by choosing the path that endures rather than the path that risks escalation. Danya’s loyalty to Malka and Imma is steady, even when her support is reluctant or exhausted, and her eventual willingness to back Malka’s hunt shows a buried hope that life can be more than waiting for the next blow.

In the closing shift back to rebuilding Eskravé, Danya’s role becomes quietly revolutionary: she helps create a future not under curfew or terror, which suggests her growth from a battered girl into a co-architect of renewal. Danya’s character underscores that heroism doesn’t only look like entering the forest with a dagger; sometimes it looks like staying alive through years of harm, and still choosing to help someone else fight.

Hadar

Hadar, the youngest sister, carries the innocence that the village has almost forgotten how to protect. She is not deeply present in the action, but emotionally she anchors Malka’s sense of what is at stake.

Hadar’s paper cuttings and small, fragile creations represent childhood in a world designed to extinguish it. She also embodies memory and continuity, especially once the story moves into its epilogue; Malka restoring Hadar’s cuttings with Kefesh is not only a tender act but a symbolic reversal of the forest’s thefts.

Through Hadar, the book emphasizes that the fight against monsters and tyrants is ultimately about preserving ordinary tenderness.

Amnon

Amnon is introduced as Malka’s friend and ally, and his character is built around devotion that is both genuine and complicated. He is brave, outspoken against the Church, and instinctively protective, but that protectiveness sometimes crosses into paternalism, especially when he insists on joining Malka’s hunt.

His desire to shield her is inseparable from his need to matter in a world where Yahadi men are repeatedly humiliated—by the Rayga, by the Paja, by illness. Amnon’s arc traces the tension between love as partnership and love as possession: he supports Malka at real cost to himself, but he also tries to define the terms of their future by proposing marriage right when she is at her most desperate.

This moment is not villainous; it is painfully human, revealing how even good intentions can be shaped by gendered expectations and fear of losing someone. He remains loyal through the forest horror and palace escape, and he offers to take Nimrah’s rooting burden, which speaks to self-sacrifice.

Yet his place in the story subtly decreases as Malka’s bond with Nimrah becomes central, positioning Amnon as a meaningful but not ultimate companion in Malka’s life. He is a portrait of the supportive friend who must learn that protection sometimes means stepping back.

Nimrah

Nimrah is the story’s most haunting and transformative figure, evolving from mythic threat to intimate partner without ever losing her uncanny weight. She begins as the towering golem rooted to the Great Oak—stone-and-vine, carved with Yahadi letters, created to protect yet trapped as the source of the forest’s curse.

Nimrah’s identity is a knot of paradoxes: she is both monster and guardian, both weapon and victim, both ancient magic and vulnerable soul. Her calm, deliberate speech and careful healing of Malka immediately complicate the villagers’ terror of the Rayga, revealing a moral consciousness beneath the inhuman body.

Nimrah’s rage at the Maharal’s imprisonment shows fierce loyalty and a deep sense of purpose, but her existence also raises unsettling questions about responsibility: she is the cause of the monsters, yet not by intent; her very being has been misused by Ozmini theft and Yahadi sacrifice. Her proposed bargain to surrender herself in exchange for Imma’s freedom is a turning point that reframes monstrosity as something imposed, not inherent.

The severing of her bond with Malka and her later forced killing of Prince Evžen under Sévren’s command make her the site where agency and control are most brutally contested. Nimrah’s plea for Malka to kill her rather than be weaponized is one of the clearest expressions of her humanity.

In the ending, her restored “emet” and romantic union with Malka do not sanitize her past; instead, they affirm that love can grow between two beings forged in violence, as long as it is chosen freely. Nimrah embodies the novel’s thesis that monsters are often made, not born, and that reclaiming selfhood is its own kind of liberation.

Aleksi

Aleksi is an Ozmini Paja rider whose personal decency stands in contrast to the institution he serves. He is curious, flirtatious, and capable of listening to Malka in ways other Ozmins refuse, which makes him a small but meaningful bridge between worlds.

His skepticism about the Rayga’s reality is not simple arrogance; it reflects the insulated faith of someone who has never needed to believe in Yahadi terror to survive. Still, he shows flickers of empathy—defending Malka with the lie that she was with him, warning her to stay quiet to live—and those acts demonstrate moral instinct even under indoctrination.

Aleksi’s death in Mavetéh is abrupt and brutal, underscoring how unprepared he is for the true horror of the forest and how little the Church’s rhetoric protects anyone in practice. As a character, he represents the possibility of humane individuals within oppressive systems, and also the tragedy of how those systems consume even their softer members.

Václav

Václav is the clearest human antagonist early in the story, embodying Ozmini cruelty stripped of ambiguity. His harassment of Sid, violence toward Amnon, and constant suspicion of Yahadi “magic” reveal a man addicted to dominance.

Unlike Aleksi, Václav’s faith is a weapon rather than a worldview; he uses it to justify humiliation and control, and he treats the Yahad as inherently deceitful, a prejudice that makes him dangerous even before the forest amplifies fear. In Mavetéh, his reaction to Aleksi’s mauling—turning on Malka and Amnon, attempting to sacrifice Malka to the Rayga—shows that his hatred is stronger than survival sense.

His death by slipping and smashing his head is almost symbolically banal: not a glorious martyrdom but a consequence of his own brutality and panic. Václav’s function is to show how monstrousness can be fully human, long before any creature crawls from a tree.

Father Brożek

Father Brożek serves as the face of the Order of the Paja’s predatory theology. He arrives armed with certainty, demanding impossible tithes from a starving village and performing public violence—like Minton’s amputation—to remind everyone that Ozmini power is absolute.

Brożek interprets the forest crisis not as a shared tragedy but as proof of Yahadi guilt, and he weaponizes Rzepka’s death to accuse Imma of sacrifice. His readiness to accept Malka’s bargain is less mercy than spectacle; he anticipates her failure and wants a ritualized execution to reinforce authority.

Brożek is not shown to evolve or doubt, which is intentional: he represents institutional violence that does not require personal hatred to be lethal. Even when he recedes from the later plot, his influence lingers in the desperate terms Malka must accept, proving how religious tyranny can shape lives from afar.

Rzepka

Rzepka is a brief but catalytic presence whose death ignites the main conflict. She is confident in Ozmini protection and dismissive of the Rayga’s threat, which positions her as someone who benefits from faith’s promises without understanding the risks others bear.

Yet her youth, social ease, and casual camaraderie with Malka also suggest she is not malicious—just sheltered. The scene of her mauled body in the snow is horrifying not only for its gore but for what it reveals: Ozmini privilege does not equal safety, and the forest’s violence disrupts every hierarchy.

Rzepka’s death becomes a tool used by Brożek and later Sévren, reducing her personhood to political fuel. In that sense, she symbolizes how women’s bodies are appropriated by power, regardless of which side they belong to.

Chaia

Chaia is the story’s embodiment of survival against narrative expectation. Believed dead for years, she reappears alive in Valón, reshaping Malka’s understanding of loss and possibility.

Chaia is quick-witted, grounded, and quietly radical; she has adapted to palace life as a scullery maid and uses her position to aid Yahadi resistance. Her loyalty to Malka is immediate and fierce, and she throws herself into the Maharal rescue with the urgency of someone who has already escaped one kind of death and refuses another.

Chaia also brings a sharper political consciousness than Malka initially wants—she understands reform networks, schisms, and alliances—making her a guide into the larger world beyond Eskravé. After Vilém’s death, Chaia’s grief is raw and unperformative, yet she continues forward, traveling with Nimrah and Sigmund to protect Yahad communities.

Chaia represents the part of Malka’s past that refuses to stay buried, becoming instead a companion in the future’s shaping.

Vilém

Vilém is defined by steadiness and hopeful defiance. As Chaia’s betrothed and a participant in the reform network, he bridges personal love with communal responsibility.

His willingness to help Malka and Nimrah into the palace reflects a belief that survival requires organized courage, not isolated acts. Vilém’s dream that the Maharal officiate his wedding is more than sentiment; it is a political and spiritual claim that Yahadi life will continue publicly, not just in hiding.

His death in the clocktower battle—stepping in front of Chaia as Sévren’s wild magic hurls a rock—crystallizes his nature as someone who protects through action rather than rhetoric. He dies tenderly, comforting Chaia, leaving behind not only sorrow but a legacy of commitment that the survivors choose to continue.

Eliška

Eliška functions as a quiet enabler of resistance through knowledge rather than force. By providing the old palace chapel floorplan and explaining the tunnel logic, she gives the group a path that brute strength alone could never find.

Her presence highlights the importance of memory, archives, and inherited understanding in fighting oppressive systems. Eliška is less a fully developed emotional arc and more a symbol of intergenerational Yahadi resourcefulness—people who safeguard fragments of truth until the moment someone is ready to use them.

Katarina

Katarina is a practical revolutionary, operating at the seam between ordinary life and covert rebellion. As a tailor and reform-network member, she provides disguises, safe spaces, and political context, showing how resistance is sustained by tradespeople and organizers, not just fighters.

Katarina’s explanation of the papal schism and secular movements situates Malka’s personal mission within a broader upheaval, and she helps Malka recognize that the Church’s cruelty is not inevitable but historically contingent. Her role after Vilém’s death—bringing news of Imma’s rescue—reinforces her as someone who keeps the collective thread intact even in chaos.

Archbishop Sévren

Sévren is the novel’s final human embodiment of corruption, combining religious authority with stolen magic and ruthless political calculation. Unlike Brożek’s blunt oppression, Sévren’s evil is strategic and theatrical: he manipulates Prince Evžen, undermines King Valski by poisoning his medicine with liquor, and engineers public terror by using Nimrah to assassinate the prince.

His carving of Yahadi command letters into his own body shows a sacrilegious hunger for control—he wants Kefesh not to understand it, but to dominate through it. Sévren’s sickness from misuse of magic mirrors moral rot: power that violates life’s rules consumes the violator.

His public punishments, like forcing Malka to witness the gatekeeper’s torture, reveal a man who believes fear is the purest form of governance. Yet his death is also fittingly mechanical and impersonal—crushed by clocktower gears—suggesting that the systems he tried to freeze in place ultimately grind him down.

Sévren is not a complex sympathizable villain; he is complexity weaponized, a warning about what happens when ideology marries unchecked ambition.

Prince Evžen

Prince Evžen is portrayed more as a political object than a fully realized person, which reflects his role in the story’s power dynamics. He is a young ruler being groomed by Sévren, caught between emerging secular pressures and the Ozmini Church’s grip.

Malka’s brief eavesdropping on his conversation reveals someone being pushed toward harsher rule, suggesting he is malleable rather than inherently cruel. His murder on the Léčrey stage transforms him instantly into a martyr figure for Ozmini propaganda, demonstrating how leadership bodies can be appropriated by larger agendas.

Evžen’s death is less about his personal fate than about the chaos it unleashes, marking him as a pivot point in the struggle for narrative control.

King Valski

King Valski appears as a decaying symbol of a monarchy hollowed out by Church influence. Drunk during the festival and quietly diminished under Sévren’s manipulation, he represents the failure of traditional authority to protect anyone, Ozmin or Yahad.

His weakness is not only personal but systemic: the throne is shown as vulnerable to ideological capture, and his decline opens the way for Duke Sigmund’s rise. Valski is a cautionary figure of what happens when rulers outsource moral responsibility to religious power.

Duke Sigmund

Sigmund is a looming political force who becomes ruler in the aftermath, embodying the shift toward secular authority. Though he remains mostly offstage, his presence in conversations and the epilogue signals pragmatic, if uncertain, hope for the Yahad.

Sigmund is not framed as a savior; rather, he is part of a changing world where Church dominance can be contested. His alliance with Chaia and Nimrah to protect Yahadi communities suggests a ruler willing to deal in realities rather than dogma, positioning him as a stabilizing, if politically complex, future.

Minton

Minton, the metalsmith whose hand is amputated, represents the village’s crushed dignity under Ozmini extraction. His protest is grounded in truth—Eskravé’s poverty stems from the Rayga and cursed woods—and his punishment is a deliberate performance meant to terrify everyone else into silence.

Minton’s later infection and suffering also show the lingering cost of symbolic violence: the Church’s spectacle doesn’t end when the cleaver falls; it echoes in bodies and minds. He is a minor character, but his fate sets the emotional tone for Malka’s revolt.

Bori

Bori is Aleksi’s younger brother and a small window into the ordinary humanity within the Paja ranks. His presence in the forest-edge camaraderie scene suggests youth still capable of friendship and curiosity, which makes the Paja system feel less like a monolith of villains and more like a machine that recruits people before shaping them.

Though he does little directly, Bori helps frame Aleksi’s decency and the tragedy of what the Church trains its members to ignore.

Hajek

Hajek, the reformist preacher burned at the stake, is a background figure whose death illustrates the high stakes of ideological dissent within Ozmini society. His execution signals that even Ozmins who challenge the Church are treated as existential threats, reinforcing the theme that tyranny devours its own.

Hajek’s fate feeds the reform network’s urgency and contextualizes why Katarina and Chaia operate in secrecy.

The Maharal of Valón

The Maharal is the spiritual and intellectual heart of Yahadi magic and tradition, and also a tragic architect of unintended consequences. His creation of Nimrah as a protector reveals a deep commitment to safeguarding Yahad lives, yet his prayers being stolen by Sévren and used to create a twisted golem bride demonstrate how knowledge can be weaponized when torn from its ethical roots.

The Maharal’s imprisonment—emaciated, hands cut off—shows the Church’s fear of Yahadi power and its willingness to break sacred bodies to maintain dominance. In the end, his decision to sacrifice himself to destroy the Great Oak is not only a heroic closure but a moral reckoning: he takes responsibility for ending a curse tied to his craft, even at the price of his life.

His death lifts the forest blight and frees the community, making him a figure whose legacy is both sorrowful and foundational to the fragile hope that follows.

Themes

Oppression, Religious Authoritarianism, and the Machinery of Power

Life in Eskravé is shaped as much by the Rayga as by the Ozmini Church, and the story repeatedly shows how institutional power feeds on fear. The Paja do not arrive as caretakers or protectors; they arrive as extractors.

Their tithe demands are calibrated to keep the village desperate, because desperation makes obedience easier to enforce. The public amputation of Minton’s hand is not about correcting one man’s defiance; it is a demonstration staged for everyone watching.

Violence becomes a ritual language the Church uses to say: your bodies and labor belong to us. This logic is echoed later in Valón, where punishment becomes spectacle at the palace gate.

The flaying of the gatekeeper is meant to rewrite reality in public, making cruelty look like justice and making submission feel like survival.

What makes authoritarianism especially dangerous in The Maiden and Her Monster is its ability to reshape stories. Brożek accuses Imma of witchcraft immediately after an Ozmini woman dies, because blaming a Yahadi healer protects Church authority, even when there is obvious evidence of a monster.

The institution does not need truth; it needs a usable narrative that keeps hierarchy intact. Sévren embodies that same principle at a higher level.

His manipulation of the king’s health, his grooming of Evžen, and his orchestration of a martyr’s death show that power is maintained not just by force, but by crafting dependency. He decides who is holy, who is criminal, and who is human enough to be mourned.

The Yahadi communities are not only oppressed economically and physically but also epistemically: their knowledge is dismissed as superstition unless it serves Ozmini interests. Kefesh is feared when Yahad use it and weaponized when Sévren steals it.

That double standard is the story’s clearest indictment of empire and church-state control. The novel’s political shift at the end does not pretend oppression vanishes when one ruler falls; instead, it suggests that power systems mutate.

Safety for the Yahad improves under Sigmund, but tension remains, reminding us that liberation is a process, not a clean event.

Fear, Scapegoating, and the Making of “Monsters”

The forest curse and the Rayga create a social environment where terror is ordinary, and the story explores what fear does to communities. Curfews, drunken hunts, and whispered prayers are ways Eskravé tries to cope, but they also keep everyone locked in a cycle of helplessness.

When people are trapped in that cycle, they look for a face to attach to their dread. The Rayga’s attacks on women make the village treat the forest like a moral judge instead of a natural threat, and that shift primes them to accept scapegoating when the Church offers it.

Imma’s arrest is the clearest example. A Yahadi woman stands over a dead Ozmini body, and the institutional response is instant certainty: witchcraft, sacrifice, treason.

The need to identify a human culprit outweighs any commitment to understanding what really happened. This is how fear becomes political fuel.

The Paja have no practical solution to the monster problem; instead, they redirect fear toward the Yahad. Sévren later magnifies this strategy by ordering Nimrah to kill Evžen.

He does not merely want a dead prince; he wants a death that points the crowd’s rage toward an already vulnerable group. The mob forming in Ordobav shows how quickly fear turns people into weapons.

They are not born cruel; they are manipulated into thinking cruelty is defense.

The theme becomes more complex through Nimrah. She is called the Rayga, then revealed as a golem who never chose to be the curse’s source.

The book asks what a “monster” really is: a creature made dangerous by circumstance and control, or a person who chooses domination and harm. Nimrah’s body is literally inscribed with command letters, making her a tool whenever someone seizes that language.

Her moments of resistance show that monstrosity is not inherent to her; it is imposed. Sévren, in contrast, is physically human and socially revered, yet uses magic and religion to commit atrocities.

The inversion is deliberate: the real monster is the one who weaponizes fear for power.

By the end, the destruction of the Great Oak clarifies that curses can be historical, built from old violence that continues to poison the present. The forest’s horrors are not random; they come from stolen prayers, forced resurrection, and the refusal to respect boundaries of life and death.

Fear in the novel is never just an emotion. It is a system that can either be confronted with truth and solidarity or exploited to keep oppression alive.

Gendered Violence, Patriarchy, and the Cost of Being a Daughter

From the opening pages, the danger in Eskravé is gendered. The Rayga takes girls and women, curfews are meant to protect them, and yet those same curfews underline how little safety they actually have.

Women become both the most vulnerable targets and the symbols around which the village organizes its dread. Malka walks through a world where her body is always at stake: the monster hunts her after dark, the Paja view her as prey in daylight, and even her home contains threats that are quieter but constant.

Abba’s abuse of Danya brings patriarchy into the family space. The text does not present this violence as a separate issue from the village’s larger suffering; it shows how scarcity, humiliation, and fear reproduce cruelty inside households.

Abba returns from pointless hunts drunk and empty-handed, and his frustration finds an outlet in control over his daughter. Danya’s confession to Malka is a turning point because it widens Malka’s understanding of what must be fought.

Killing the Rayga is not only about curing a curse; it is about disrupting a world that treats women as expendable, replaceable, or blameworthy.

The Church’s violence toward women mirrors this pattern. Rzepka dies because she assumes religious identity makes her untouchable, a tragic example of how patriarchal institutions sell women false protection.

Imma becomes a convenient scapegoat because female authority, especially in healing and spiritual knowledge, threatens Ozmini control. Malka’s bargain with Brożek is shaped by that reality: she must risk her life to prove innocence that no man would have to demonstrate so brutally.

Her journey into Mavetéh is a forced test of worth imposed on a young woman because the world already expects her to suffer for family survival.

At the same time, the novel insists on women’s resilience and agency without romanticizing their pain. Malka’s work delivering medicine, Chaia’s secret networks, Katarina’s organizing, and Nimrah’s protection all show forms of power that are communal rather than hierarchical.

Even Malka’s relationship with magic grows partly from care: she wants to heal, to safeguard, to restore. The final rebuilding of Eskravé under Malka and Danya, with Imma choosing her own path and Nimrah traveling as a guardian, sketches a future where women direct the shape of life rather than absorb its punishments.

Gendered violence remains a haunting presence, but the story refuses to let it be destiny.

Kefesh, Knowledge, and Responsibility

Magic in The Maiden and Her Monster is not a neutral tool; it is a form of knowledge tied to history, culture, and ethics. Kefesh can heal, grow perphona, animate stone, and bind life to life.

Because of that scope, every use of it carries moral weight. Malka begins with a practical relationship to Kefesh through Imma’s medicine and the survival needs of Eskravé.

As her power awakens, she experiences both awe and anxiety. She senses how easily abilities meant for care can become instruments of domination, especially in a world already tilted toward violence.

The Maharal stands as the ethical center of this theme. His study of Kefesh is rooted in protection of Yahad, not conquest.

Yet even his creations have consequences beyond his intention. Nimrah is made to guard, but her rooting to the Great Oak turns her into the curse’s source.

The story treats that not as personal failure alone but as a reminder that knowledge interacts with politics and chance in unpredictable ways. The Ozmini theft of golem prayers is the clearest warning: when sacred knowledge is ripped from its moral framework, it becomes lethal.

Sévren uses stolen Kefesh with no restraint, carving command letters into his own arm and Nimrah’s skin, and his body begins to decay from that misuse. The illness is more than punishment; it is narrative evidence that power without responsibility corrodes the wielder.

Malka’s arc is a study in learning that responsibility cannot be avoided. She tries to refuse Kefesh early on, fearing what it could make her, but need keeps pulling her back.

Her decision to scratch the letter on Nimrah’s forehead instead of killing her is a moment where ethics guides magic. She finds a third path between obedience to a bargain and the easy answer of destruction.

Later, the Maharal’s final sacrifice frames responsibility at its most severe scale: he chooses death because he knows destroying life fashioned by Kefesh costs the destroyer’s life. The rule insists on accountability embedded into creation itself.

The theme also interrogates who gets to define “legitimate” knowledge. The Church condemns Yahadi magic as evil while quietly exploiting it.

That hypocrisy shows that the conflict is not about the danger of Kefesh, but about who controls it. By the end, Malka’s continued use of magic for restoration, memory, and healing suggests a model of power aligned with repair rather than fear.

Kefesh becomes a language of survival and community when paired with humility and care, and a language of tyranny when paired with entitlement.

Love, Bonding, Grief, and the Work of Renewal

Relationships in the novel are not side plots; they are the engine of survival. Malka’s decisions are constantly shaped by ties to others: her loyalty to Imma, her protectiveness toward Hadar, her guilt and hope around Chaia, her complicated trust in Amnon, and her destiny-bound connection with Nimrah.

The story treats love as something forged under pressure. When communities are sick, hunted, or crushed under tithe demands, affection becomes a lifeline rather than a luxury.

The rooting spell between Malka and Nimrah makes this theme concrete. At first, the bond is coercive, framed as a bargain needed to save Imma.

Malka experiences nausea, disorientation, and a sense of being invaded. Yet through shared danger and honesty, the bond becomes mutual recognition.

Malka learns Nimrah’s origin, Nimrah learns Malka’s grief, and what starts as necessity turns into partnership. Their eventual romantic relationship is not a sudden switch but the culmination of trust built through injury, rescue, argument, and choice.

The novel insists that intimacy is not about perfection; it is about refusing to abandon each other’s humanity even when the world labels one of you a monster.

Grief is the shadow twin of love here. The yahrzeit candle for Chaia, the memory of missing women, the terror of losing Imma, and later Vilém’s death all show how mourning shapes identity.

Malka’s world is one where absence is normal, and the story does not rush past that. Vilém’s sacrifice is especially painful because it happens during a moment meant to expose evil and reclaim safety.

His death makes clear that victory never arrives untouched. Chaia’s survival earlier challenges Malka’s assumptions about loss, showing that grief can be revised, but not erased.

Renewal is presented as active labor rather than a magical reset. The forest curse lifts only through the Maharal’s death, and even after that, rebuilding requires human hands and patient choices.

Malka returns to care for her family, repair her village, and keep Hadar’s paper cuttings alive through Kefesh. Nimrah steps into a protector role that continues the Maharal’s unfinished projects.

These acts are quiet compared to battles in the clocktower, but they are the book’s final argument: healing is not a single moment of triumph, it is what people do afterward, daily, while carrying both love and grief in the same body.