The Man No One Believed Summary, Characters and Themes

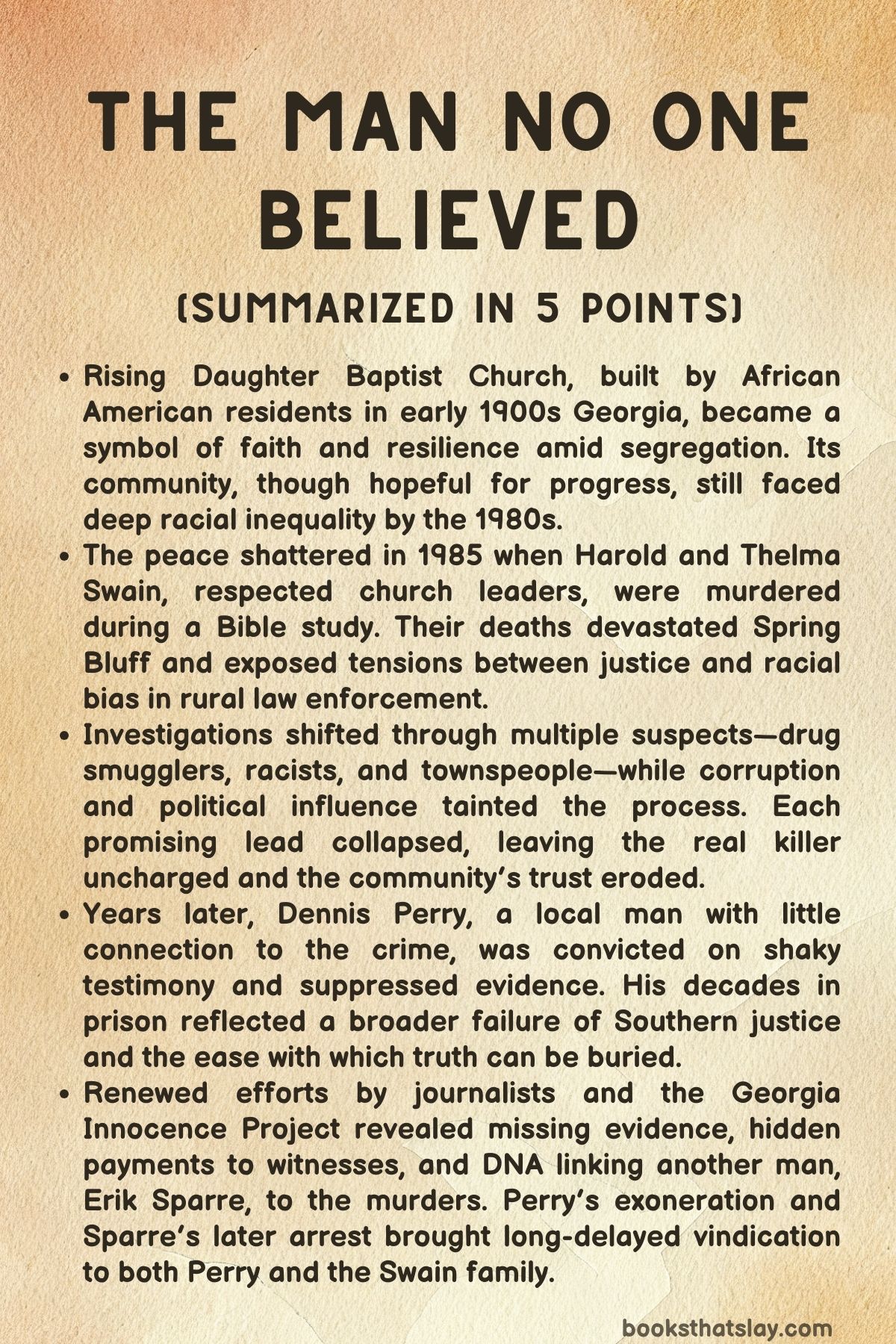

The Man No One Believed by Joshua Sharpe is a haunting true-crime chronicle that examines a decades-long miscarriage of justice in the Deep South. Set in Georgia, the book follows the 1985 murders of Harold and Thelma Swain—an elderly Black couple gunned down in their small church—and the tangled, racially charged investigation that followed.

Through meticulous reporting, Sharpe exposes systemic corruption, small-town prejudice, and the tragic consequences of flawed policing. The story becomes not only about one man wrongfully imprisoned, Dennis Perry, but also about a community’s painful reckoning with its history and the enduring power of truth to emerge, even after generations of silence.

Summary

In the early 20th century, the Rising Daughter Baptist Church in rural Coastal Georgia stood as a cornerstone of hope for Black families enduring the aftermath of slavery and segregation. By 1985, that legacy of faith and perseverance was shattered when Harold and Thelma Swain, a beloved elderly couple, were murdered during a Monday night Bible study.

The killer—a white man in his twenties with light hair and glasses—entered the church, asked for Harold, and moments later shot both Harold and Thelma in cold blood. Their deaths devastated the Spring Bluff community and highlighted the deep racial and social divides that lingered beneath the surface of the South.

Investigators Deputy Butch Kennedy and Georgia Bureau of Investigation agent Joe Gregory took on the case. They found the couple’s bodies in the church vestibule, along with blood, shattered glasses, and cut phone lines.

A pair of mismatched eyeglasses with blond hairs became a critical clue, but despite numerous witnesses describing the suspect, no arrest followed. Officials dismissed racial motives and suggested robbery or drugs, though nothing had been stolen.

Amid local corruption under Sheriff Bill Smith, the investigation grew stagnant, and the killer remained free.

Months later, a potential lead surfaced when inmate Jeffrey Kittrell told police that his associate, Donnie Barrentine, had bragged about killing two Black people in a church. Barrentine matched the suspect’s description and had even spoken of cutting phone lines—an exact detail from the crime scene.

Despite his eerie similarities to the witness accounts, investigators lacked hard evidence and failed to charge him. Rumors spread of deeper corruption, drug smuggling, and power struggles within Camden County.

The Swains’ deaths faded into memory, unsolved and unresolved.

Years passed, and in 1988 the case was featured on Unsolved Mysteries, which reignited public interest. Among the new tips was a name—Dennis Perry, a Spring Bluff native.

Initially, Perry was ruled out because he had an alibi: he lived hours away near Atlanta and lacked transportation. Still, as other suspects were dismissed, Perry’s name resurfaced.

In the late 1990s, when Sheriff Smith reopened the case, he assigned investigator Dale Bundy to lead it. Bundy’s inquiries reignited the old rumors and drew on questionable witnesses.

Chief among them was Jane Beaver, the mother of Perry’s former girlfriend, who claimed Perry had once vowed to kill Harold Swain after a personal dispute. Her story shifted over time, but Bundy treated it as decisive.

When Bundy presented Perry’s photo to surviving witnesses, their identifications were uncertain. Despite this, Bundy pressed forward, and in 2000, Perry was arrested and charged.

At trial in 2003, the prosecution relied heavily on Beaver’s testimony, supported by vague witness statements from church members decades after the event. Critical evidence, including the glasses and potential DNA material, was missing.

The defense highlighted inconsistencies and corruption in the sheriff’s office but could not overcome the prosecution’s narrative. Perry was convicted of both murders and sentenced to life imprisonment, despite maintaining his innocence.

Prison became Perry’s harsh reality. Confined to violent Georgia prisons, he endured years of isolation and abuse.

Over time, he found solace in faith and writing, while his family—believing in his innocence—fought tirelessly for his release. The case took new turns as journalists, including Susan Greene from The Denver Post, uncovered missing evidence and corruption within the sheriff’s department.

Beaver’s credibility unraveled when it emerged she had secretly received a $12,000 payment from authorities—a detail hidden from the defense. Meanwhile, DNA testing on the old glasses revealed a startling result: the hair found at the crime scene belonged to the maternal line of Erik Sparre, a violent white supremacist who had long bragged about killing Black people in a church.

As the Georgia Innocence Project joined Perry’s cause, more witnesses came forward claiming Sparre had confessed to the murders. His former wives and even his son described his racism and violent nature.

Investigators discovered that Sparre’s supposed alibi from his grocery store job was fabricated, and the man who vouched for him never existed. Confronted with the mounting evidence, Sparre denied involvement, but the tide had turned.

In 2020, Judge Stephen Scarlett ruled that Perry’s conviction was based on a miscarriage of justice. Perry was released from prison after twenty years, finally reuniting with his wife, Brenda, who had stood by him through decades of wrongful imprisonment.

In freedom, Perry faced both joy and loss. He had missed decades of life—his parents’ deaths, friends’ aging, and the world’s transformation—but he found peace in small things: church gatherings, family meals, and moments by the river.

Meanwhile, the investigation into Sparre continued. His property was searched, revealing Confederate memorabilia and evidence of his extremist beliefs, but no direct link to the murder weapon.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation exhumed Harold Swain’s body for new DNA testing, though results were inconclusive.

In 2021, prosecutors dropped all charges against Perry, acknowledging that justice demanded correcting past wrongs. He was officially exonerated and awarded $1.

4 million in state compensation for his wrongful imprisonment. Perry and Brenda settled near their hometown, finding comfort in each other and their community.

Still, questions remained about why Sparre had escaped scrutiny for so long and how systemic racism and corruption had shaped the case.

The story reached closure in late 2024, when authorities finally charged Erik Sparre with the murders of Harold and Thelma Swain. His arrest brought long-awaited justice to the Spring Bluff community and vindication to the investigators and journalists who had pursued the truth.

For Dennis Perry, the man no one believed, freedom came with scars but also with redemption—a reminder that persistence, truth, and courage can outlast even the darkest injustices.

Characters

Harold Swain

Harold Swain stands as the moral and spiritual pillar of The Man No One Believed, embodying integrity, humility, and devotion. A deacon at Rising Daughter Baptist Church, he dedicates his life to service—guiding his community through both faith and action.

His leadership is not authoritarian but compassionate, built on empathy and quiet strength. Harold’s daily work at Choo Choo BBQ and his role in the NAACP reflect his dual commitment to sustenance and social justice.

Yet his murder transforms him from a man of the people into a symbol of racial and moral injustice. Harold’s character evokes the image of the ordinary hero—an everyman whose death exposes the deep fractures of Southern society and the negligence of institutions meant to protect him.

His unwavering belief in goodness becomes tragically ironic in a world that repays faith with violence.

Thelma Swain

Thelma Swain mirrors her husband’s steadfastness, but her essence is defined by compassion and resilience. Her role in The Man No One Believed extends beyond being Harold’s wife—she is the emotional anchor of her family and a beacon of kindness in Spring Bluff.

Thelma’s devotion to family, her church, and her community forms a quiet counterpoint to the brutality that ends her life. Her death is doubly tragic: it is both a personal loss and a symbolic silencing of maternal care in a society where such voices often go unheard.

Thelma represents dignity amid oppression, and in her final act—rushing toward danger to save Harold—she personifies love’s ultimate courage.

Dennis Perry

Dennis Perry’s arc drives the narrative’s emotional core. Wrongly convicted for the Swains’ murder, he becomes the titular “man no one believed.

” Initially portrayed as an ordinary, soft-spoken man, his story unfolds as a harrowing journey through systemic injustice. His wrongful imprisonment strips him of decades, health, and identity, yet his endurance transforms him into a symbol of perseverance against corrupt power.

Perry’s quiet faith, reflective intellect, and humanity shine even within the inhumanity of prison life. Through letters, love, and introspection, he reclaims his dignity.

His eventual exoneration does not erase his suffering but redefines him—from victim to survivor. Perry’s journey indicts the machinery of justice, exposing how bias and ambition can warp truth itself.

Dale Bundy

Dale Bundy represents the flawed face of institutional authority in The Man No One Believed. A former deputy turned investigator, he reopens the Swain case years later but does so with tunnel vision and prejudice.

His reliance on dubious witnesses and coerced testimony illustrates the dangers of confirmation bias. Bundy’s methods—manipulating statements, ignoring inconsistencies, and pushing for an easy conviction—reflect not individual malice alone but a systemic rot where career advancement eclipses truth.

His portrayal underscores how investigators can become unwitting architects of injustice when driven by the illusion of certainty rather than the pursuit of fact.

Jane Beaver

Jane Beaver is the most complex and tragic secondary figure in the story. Her testimony becomes the cornerstone of Perry’s conviction, yet it is riddled with inconsistencies and delusion.

She shifts timelines, fabricates events, and conflates memories—traits rooted perhaps in loneliness and psychological fragility rather than malice. Beaver’s lies are not just personal failings; they are institutionalized through a justice system willing to accept any narrative that fits its needs.

She embodies the theme of belief and deception—how truth becomes distorted when filtered through human frailty and systemic pressure.

Butch Kennedy

Deputy Butch Kennedy emerges as one of the few figures of moral clarity. His early investigation into the Swain murders is marked by diligence and sincerity, even as he confronts racial tension and bureaucratic interference.

Kennedy’s later remorse over Perry’s conviction reflects his deep conscience and his disillusionment with law enforcement’s corruption. In retirement, he becomes a quiet champion for justice, haunted by the truth that he once helped suppress.

Kennedy’s evolution—from investigator to truth-seeker—makes him a moral compass in a story clouded by deceit.

Joe Gregory

Agent Joe Gregory complements Kennedy as a partner in integrity, though he is ultimately constrained by the same flawed system. His investigative instincts are sound, but his authority limited.

Gregory’s later support for Perry’s innocence suggests that while institutions may fail, individual conscience can endure. His partnership with Kennedy reflects an unspoken acknowledgment that the pursuit of justice requires humility and the courage to admit error.

Erik Sparre

Erik Sparre represents the story’s chilling embodiment of hate and hypocrisy. A white supremacist and habitual liar, Sparre hides behind false alibis and family respectability while boasting of racial killings.

His connection to the crime through DNA evidence transforms him from a peripheral suspect into the embodiment of evil long concealed by privilege. Sparre’s racism, violence, and manipulation expose the darker undercurrents of Southern identity—the persistence of hatred cloaked in normalcy.

His eventual arrest, decades later, symbolizes not triumph but reckoning—a delayed confrontation between truth and the lies America tells itself about race and justice.

Brenda Perry

Brenda Perry, Dennis’s wife, personifies unwavering love and resilience. Her entrance into Dennis’s life during his imprisonment reawakens his hope and humanity.

Through letters, visits, and steadfast loyalty, she restores meaning to a man nearly erased by the system. Brenda’s character illuminates the theme of redemptive love—how compassion can outlast despair.

Her fight for Dennis’s freedom and her endurance amid personal suffering transform her into a quiet hero, representing the countless women who hold families and faith together in the face of systemic cruelty.

Sheriff Bill Smith

Sheriff Bill Smith epitomizes corruption, ego, and the moral decay of power. Charismatic yet self-serving, he uses his authority for political gain and personal enrichment.

His manipulation of investigations and misuse of resources illustrate how justice can become a commodity. Smith’s secret payment to Jane Beaver and his exploitation of inmates for private labor expose the deep rot beneath the surface of law enforcement.

In contrast to men like Kennedy, Smith is the cautionary face of unchecked authority—proof that the real danger often lies not in the criminals outside the law, but in those who wear its badge.

Lawrence Edward Brown

Lawrence Edward Brown, Harold Swain’s son-in-law, serves as a shadowy link between morality and corruption. His entanglement with drugs and his role as an FBI informant complicate the moral landscape of The Man No One Believed.

Brown’s story weaves the personal into the political, revealing how poverty, racism, and survival intertwine. His conflicts with Harold and his connection to criminal networks underscore the fragile line between sin and necessity in a world where justice is unevenly distributed.

The Community of Spring Bluff

Though not a single character, the Black community of Spring Bluff functions as a collective protagonist. Their church, Rising Daughter Baptist, stands as both sanctuary and symbol—a testament to endurance and faith.

The community’s silence, grief, and eventual outcry reveal the generational trauma of systemic racism. They are witnesses not just to a murder but to a century of oppression that never truly ended.

Their endurance—rooted in faith, song, and solidarity—forms the spiritual backbone of the novel and the heart of its moral argument.

Themes

Racial Injustice and Systemic Discrimination

The story of The Man No One Believed unfolds against the enduring backdrop of racial inequality in the American South, where justice often served color rather than truth. From the earliest descriptions of the Rising Daughter Baptist Church—a sanctuary born from the resilience of African Americans during the Jim Crow era—the novel reveals how the community’s faith and solidarity stood in contrast to the indifference and bias of the systems surrounding them.

The brutal murder of Harold and Thelma Swain represents not only a personal tragedy but a symbolic act of violence against a Black community that had fought for dignity for generations. The investigation that followed reinforces this theme of systemic prejudice.

Authorities dismissed racial motivations early on, even as Black residents recognized the historical pattern of violence and silence that followed such crimes. This selective blindness echoes through decades, as evidence is lost, leads ignored, and justice distorted by power structures that favored white suspects.

When Dennis Perry, a poor white man with tenuous connections, is eventually convicted despite overwhelming inconsistencies, the theme evolves into an examination of how racial dynamics intersect with class and institutional corruption. Perry’s wrongful conviction does not negate the racial underpinnings of the original crime; instead, it amplifies them, revealing how the machinery of justice could destroy lives on both sides of the racial divide while preserving the comfort of the powerful.

By tracing the arc from the 1985 murders to the 2024 arrest of the real killer, Joshua Sharpe exposes how deeply racism remained embedded not only in acts of violence but in the silence, negligence, and complicity that sustained it for decades.

Corruption and the Abuse of Power

The narrative portrays a justice system compromised by personal ambition, political influence, and greed, where truth becomes expendable in the pursuit of control. Sheriff Bill Smith’s tenure exemplifies how law enforcement authority can become a tool for manipulation.

His misuse of funds, exploitation of drug seizures, and political gamesmanship create a culture in which corruption thrives unchecked. This environment allows flawed investigators and opportunistic prosecutors to manipulate evidence and testimonies, all under the guise of seeking justice.

Dale Bundy’s reinvestigation of the Swain murders in the 1990s reflects this corrosive dynamic: rather than uncovering truth, Bundy constructs a narrative that aligns with institutional convenience. Witnesses are coerced, evidence mishandled, and doubts ignored because the system demands closure, not clarity.

The later revelation that witness Jane Beaver received an undisclosed financial reward underscores how the pursuit of conviction can supersede ethical duty. The abuse extends to the judiciary as well, where procedural rigidity is used to deny Dennis Perry the right to appeal even in the face of new evidence.

Power in The Man No One Believed is portrayed not as a force for protection but as an instrument of concealment. Those who wield it—from corrupt sheriffs to indifferent prosecutors—prioritize their careers and reputations over the truth, perpetuating cycles of injustice that destroy the very faith the public is meant to have in the system.

Through these depictions, the book illustrates that corruption in law enforcement is not merely an individual failing but a structural one, woven into the fabric of institutions that claim to uphold justice.

Faith, Resilience, and the Power of Community

Amid violence and injustice, faith emerges as both shield and sustenance for those enduring suffering. The Rising Daughter Baptist Church stands as the physical and spiritual heart of this theme—a place where generations found solace and solidarity in a world that often devalued their lives.

The murders of Harold and Thelma Swain violate this sacred space, turning a house of worship into a crime scene, yet their deaths also reinforce the endurance of belief as a source of survival. Throughout Dennis Perry’s imprisonment, faith again becomes a form of quiet rebellion.

His prayers, poetry, and friendship with his cellmate John offer him dignity in an environment designed to strip it away. Similarly, Brenda’s unwavering devotion and her visits every weekend demonstrate how faith manifests through love and perseverance, transforming personal belief into collective strength.

The community’s support—embodied in activists, journalists, and the Georgia Innocence Project—extends this spiritual resilience into civic action, revealing faith as both moral compass and catalyst for justice. Even the investigators who return to confront their past mistakes, such as Butch Kennedy, are guided by a moral reckoning that transcends institutional failure.

Through these intertwined acts of conviction, The Man No One Believed portrays faith not as blind acceptance but as an enduring assertion of humanity, capable of withstanding the weight of corruption, prejudice, and loss.

The Fragility and Reconstruction of Truth

Truth in this narrative is not static; it is contested, manipulated, buried, and slowly exhumed. From the initial investigation’s incompetence to the decades-long effort by journalists and innocence advocates, the book underscores how truth can be distorted by flawed human motives.

The early handling of the Swain case demonstrates how fragile evidence can become when filtered through bias and bureaucracy. Each retelling—from Bundy’s fabricated certainty to the later revelations of the Georgia Innocence Project—reshapes the collective understanding of what truly happened that night in 1985.

The story thus becomes a meditation on the nature of truth itself: how easily it can be lost and how painstakingly it must be reclaimed. Joshua Sharpe presents truth as something that demands courage rather than authority.

It is reconstructed not by those in power but by those persistent enough to challenge official narratives—reporters, family members, and ordinary citizens unwilling to forget. The eventual discovery of DNA evidence linking Erik Sparre to the crime scene represents both a scientific triumph and a moral vindication, proving that facts, though suppressed, can resurface when integrity persists.

Yet even in vindication, the narrative acknowledges the irretrievable damage caused by lies—the decades Perry spent in prison, the community’s shattered trust, and the lingering fear that truth may always arrive too late. Through this, The Man No One Believed examines the cost of falsehood and the redemptive but incomplete power of truth reclaimed.

Redemption and the Persistence of Hope

Despite the devastation wrought by decades of injustice, the novel concludes with a sense of hard-earned redemption that resists cynicism. Dennis Perry’s release, though delayed, becomes a testament to endurance and moral clarity.

His ability to rebuild a life—to laugh, love, and live again—demonstrates that hope can survive even in the darkest institutions. Redemption also extends beyond individuals to communities and institutions.

The actions of those who rectify past wrongs, such as the Georgia Innocence Project, the Undisclosed podcast team, and District Attorney Keith Higgins, signal the possibility of renewal within a flawed system. Their work does not erase the failures of the past but reaffirms the belief that justice can still be reclaimed through persistence and conscience.

Even for figures like Kennedy, whose late-life relief upon seeing Perry freed symbolizes moral absolution, redemption is portrayed as an emotional reckoning rather than simple closure. In the final chapters, the arrest of Erik Sparre represents not vengeance but restoration—the long-delayed alignment between truth and accountability.

Through these arcs, The Man No One Believed affirms that while the machinery of justice may falter, the human capacity for hope endures. It is this persistence—of love, memory, and moral conviction—that allows the characters and their community to transcend the ruins left by decades of injustice and finally glimpse a measure of peace.