The Maui Effect Summary, Characters and Themes

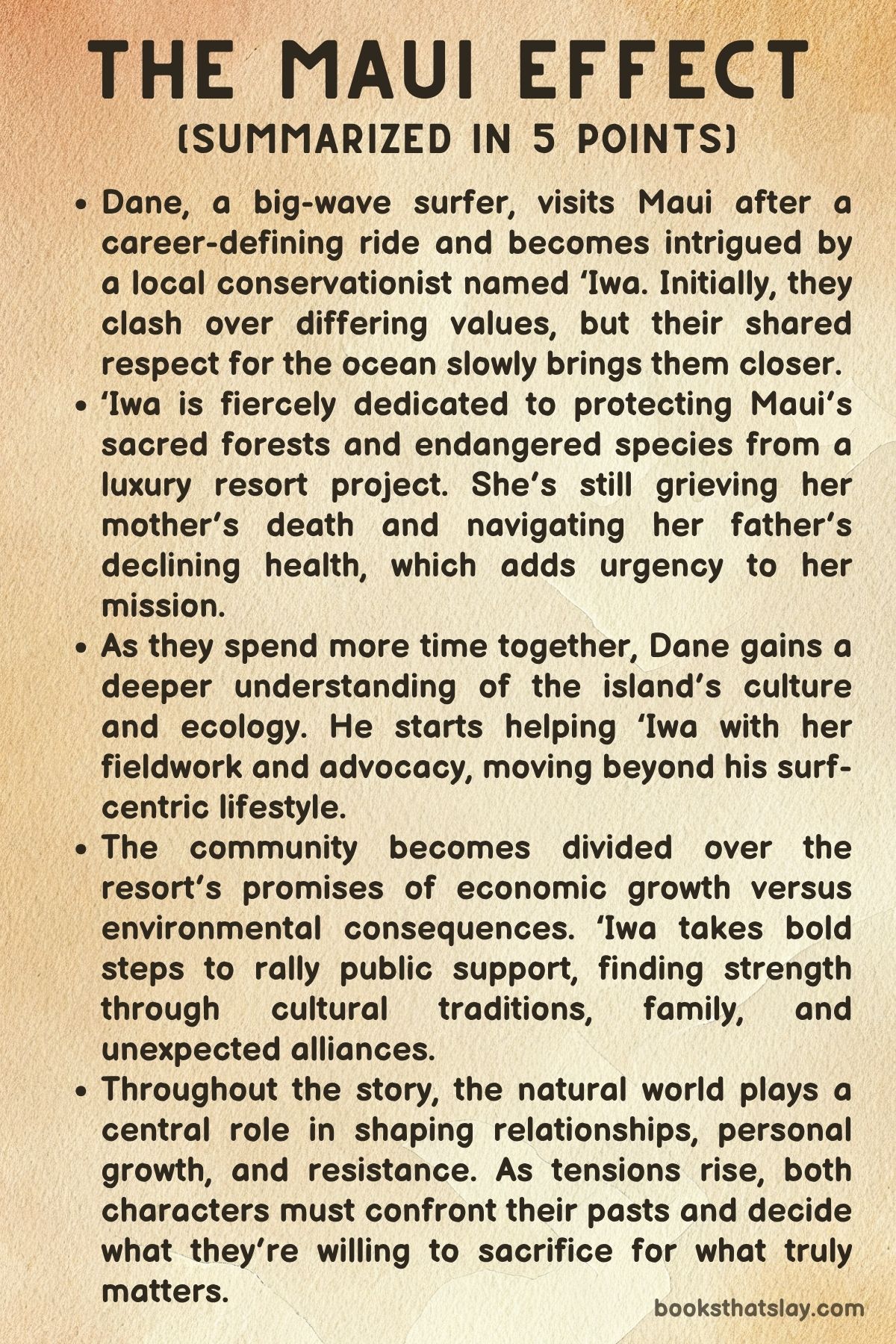

The Maui Effect by Sara Ackerman is a contemporary novel that brings together romance, environmental activism, and spiritual reflection, all rooted in the evocative setting of Maui, Hawaii. It follows two central characters—Dane, a thrill-seeking big wave surfer, and ‘Iwa, a fierce local conservationist—whose lives converge through shared passion for nature and the island’s preservation.

Ackerman crafts a narrative that is both emotionally intimate and environmentally conscious, blending personal struggles, cultural conflict, and healing journeys. As the characters navigate love, grief, ambition, and responsibility, the island becomes more than a backdrop—it becomes a mirror, catalyst, and spiritual guide for their transformations.

Summary

Dane Parsons is a professional surfer whose life has revolved around chasing massive waves, and his journey begins during a surf competition at Peʻahi—also known as Jaws—in Maui. While he waits on his board in a moment of calm before a storm, an ominous warning from a local elder—“Someone is going to die”—echoes in his mind.

As the heat nears its end and Dane remains without a solid ride, a colossal wave arrives. Dane takes it, delivering a powerful ride that earns crowd applause.

But this physical triumph surfaces a deeper longing in him—one not satisfied by adrenaline alone.

Meanwhile, ‘Iwa, a native Hawaiian woman, has returned home to Maui following the death of her mother. She’s a conservationist and waitress, deeply protective of Hana‘iwa‘iwa, a sacred natural land soon to be destroyed by a newly approved eco-resort.

Her grief is compounded by frustration with tourists who disregard local customs and damage the environment. Her love for her mother, her heritage, and her land fuels her fight against the resort.

She meets Dane at Uncle’s restaurant during an emotionally charged performance, and though sparks fly, they initially clash—‘Iwa sees Dane as just another outsider.

Yet Dane is captivated by her sincerity and depth. He approaches her again, seeking to make amends.

What begins as a “non-date” becomes an evening of shared stories and vulnerable truths. ‘Iwa recounts a formative memory of encountering a pueo—an owl symbolic in Hawaiian spirituality—and explains how it became a spiritual guide to her.

Dane opens up about his own defining moment, a shark encounter that made him more aware of mortality and connection to the ocean. Their bond begins to grow, shaped by a shared reverence for nature.

‘Iwa is cautious. Her emotional walls, built from the pain of loss and past betrayals, remain sturdy.

But Dane continues to show up—not just emotionally but physically—offering his help with her conservation work. This earns her reluctant acceptance, and together they hike through sacred lands, crossing rivers and thick forest paths.

Dane listens and learns as ‘Iwa teaches him Hawaiian ecological and spiritual customs, including the oli chant and the practice of asking permission from the forest to enter.

Their connection deepens at the enchanted waterfall Waikula, where passion and intimacy follow. But the spell is broken when guards hired by a real estate developer interrupt them, an intrusion symbolizing the broader battle between preservation and profit.

Though their emotional and physical connection is undeniable, ‘Iwa pulls away again. Dane’s upcoming departure to the mainland reignites her fears.

She tells him they can’t be together, offering him only a single opportunity to contact her—one text in two weeks—if he still feels the same.

The narrative shifts to a dramatic surf session at a dangerous break called Killers. Dane takes a huge risk and disappears beneath the waves.

‘Iwa is consumed with fear. Miraculously, he survives and is found stranded on a cliff with a dog he rescues.

This brush with death becomes a turning point for Dane, clarifying what matters. They reunite in California and continue to explore their relationship.

A road trip to the coast reveals their growing intimacy and shared advocacy for marine conservation. They debate ethical behaviors like jet skiing in protected waters, revealing that both passion and principle guide their actions.

Yet conflict resurfaces when Dane chooses to pursue a major wave at Nazaré over attending a crucial fundraiser for ‘Iwa’s conservation project. She is devastated but moves forward, delivering a powerful performance at the event that inspires a $50,000 anonymous donation.

Dane, meanwhile, suffers a wipeout at Nazaré and ends up temporarily paralyzed. In the hospital, regret floods him.

He realizes too late the gravity of his choice—he chose glory over love.

Despite everything, ‘Iwa flies to Portugal to be by his side. Though he initially pushes her away, her presence and support help him begin healing.

His physical progress—starting with the subtle movement of a toe—becomes a symbol of emotional recovery as well. They return to California together, but Dane spirals again into depression and painkiller dependency.

‘Iwa, emotionally drained, retreats to the forest for solace, seeking spiritual guidance from nature and her late mother. A confrontation with Dane’s friend forces Dane to reckon with his own emotional immaturity.

Eventually, Dane begins to heal not only physically, but emotionally. His return to surfing at Peʻahi is cautious but symbolic.

The waves once again test him, but this time his ride is less about bravado and more about restoration. When he sees a newspaper photo of ‘Iwa with another man, jealousy and fear rear their heads, yet they also push him toward clarity.

He returns to Maui, where he and ‘Iwa share a raw and painful conversation. She resists rekindling the relationship, still wounded by his choices.

The final leg of the journey takes Dane back to Nazaré, where he pushes himself once more to ride a colossal wave. It’s a test of both courage and spirit.

He not only rides successfully but also saves another surfer, Kama, from injury. This act cements a transformation in Dane—from glory-seeker to protector.

When he returns to Maui, he seeks ‘Iwa out not with grand promises, but with quiet, sincere love. This time, she meets him halfway.

Their reunion is subtle and earned, grounded in mutual growth and humility.

The story concludes with a ceremony honoring ‘Iwa’s mother. The ocean, always a steady presence, becomes the place where memory, grief, and love converge.

‘Iwa and Dane, after years of turbulence, face a future built not on fleeting passion, but on understanding, sacrifice, and shared purpose.

The Maui Effect is ultimately about what it means to truly belong—to a person, to a place, to oneself—and the courage it takes to choose love, especially when it demands more than you’re ready to give.

Characters

Dane Parsons

Dane Parsons is a character of deep complexity, driven by a blend of thrill-seeking, spiritual yearning, and emotional vulnerability. A world-renowned big-wave surfer, he initially presents as the archetype of the rugged, adrenaline-fueled athlete, constantly flirting with danger in pursuit of the perfect ride.

Yet, beneath this exterior lies a man searching for something more enduring than transient triumph. His connection to the ocean is more than professional—it is elemental and almost mystical, rooted in formative experiences like a near-death shark encounter.

Dane’s relationship with nature evolves from awe-inspired immersion to a conscious, reverent engagement, especially after meeting ‘Iwa, who expands his understanding of place, culture, and responsibility.

Dane’s emotional arc is marked by yearning—for connection, for redemption, and for purpose. His initial fascination with ‘Iwa blossoms into something profound, urging him to step outside the predictable rhythms of his surfer lifestyle.

His efforts to assist in her conservation work reflect a genuine attempt to embed himself into her world. However, his flaws are just as salient.

Dane struggles with emotional openness, especially after his catastrophic wipeout at Nazaré leaves him physically paralyzed and spiritually hollow. This moment becomes a crucible, forcing him to confront his priorities and his own mortality.

His post-recovery period is fraught with emotional withdrawal, addiction to painkillers, and a fear of inadequacy—both as a man and a partner. It is only through vulnerability and the persistence of those around him that he begins the journey back to himself.

Dane is ultimately a character who is transformed not just by love, but by the humbling power of nature and the enduring challenge of earning one’s place in the world.

‘Iwa

‘Iwa stands as the soul of The Maui Effect, a woman deeply intertwined with the land, heritage, and spiritual identity of Maui. A conservationist by profession and by heart, her life is shaped by a profound reverence for the island’s ecosystems, sacred places, and cultural traditions.

Her relationship with the land is spiritual and maternal, shaped by her late mother’s memory and her childhood experiences—especially her mystical encounter with a pueo, which becomes her symbolic guide. ‘Iwa’s fierce commitment to protecting Hana‘iwa‘iwa from invasive development is not just professional activism—it is a fight for legacy, memory, and the soul of her home.

Emotionally, ‘Iwa is layered with grief, guardedness, and integrity. Her mother’s death casts a long shadow over her, making her cautious with emotional vulnerability.

Though her attraction to Dane is immediate and visceral, she resists easy romantic resolutions. Her heart has been bruised before, and Dane’s status as a mainland outsider only deepens her skepticism.

Her emotional evolution is therefore subtle and hard-earned. Her trust in Dane grows gradually, through shared experiences, mutual respect, and his willingness to honor her beliefs and culture.

Even when wounded—such as when Dane breaks his promise to attend the fundraiser—she does not crumble. Instead, she channels her pain into purpose, delivering a powerful public speech that galvanizes community support.

‘Iwa is not a woman saved by love, but one who redefines love on her terms: rooted in respect, partnership, and shared purpose. She emerges as a figure of resilience, embodying the power of place and the strength of choosing both land and love with equal conviction.

Yeti

Yeti, Dane’s loyal friend and confidant, plays a quieter but essential role in the story’s emotional scaffolding. He represents the voice of grounded reason and emotional honesty in Dane’s otherwise tumultuous life.

From Santa Cruz to Maui, Yeti serves as both a physical anchor and an emotional mirror, unafraid to confront Dane with hard truths when avoidance and denial seem more comfortable. He is the kind of friend who holds space for grief, but also knows when to challenge it, especially when Dane begins to spiral into addiction and emotional withdrawal.

His character may not command the central narrative arc, but his influence is crucial. Yeti’s unwavering support and moments of intervention—particularly in calling out Dane’s self-isolation—help catalyze Dane’s movement toward healing.

In a narrative so driven by emotional complexity and transformation, Yeti’s role is that of the moral compass and empathetic force.

Kama

Kama, though a secondary character, carries symbolic weight as both a surfer and a grounding presence on Maui. His farm offers Dane a place of reprieve and reflection, representing a slower, more connected way of life.

Kama’s calm wisdom and rootedness contrast with Dane’s restlessness. When Dane saves him during a critical moment at Nazaré, it is not just a physical rescue—it becomes emblematic of Dane’s ability to shift from selfish pursuit to selfless action.

Kama’s existence serves as a narrative reminder of what balance, humility, and stewardship look like in practice. He, like ‘Iwa, is part of the island’s moral landscape, embodying a lifestyle that values harmony over conquest.

Themes

Environmental Stewardship and the Sacredness of Land

The Maui Effect deeply honors the relationship between humans and the natural world, particularly emphasizing the sacredness of the Hawaiian land and the urgent need to protect it. ‘Iwa’s identity is inseparable from the landscapes she fights for—rainforests, waterfalls, valleys filled with endemic life.

Her work in conservation is not just a profession but a cultural and spiritual duty, born of lineage, love, and responsibility. The forest is not merely a resource or backdrop but a living entity, one that must be respected, asked for permission, and treated as kin.

This reverence is embedded in rituals such as oli chants and the respectful entry into sacred spaces. The eco-resort threat is a violation not just of ecological integrity but of cultural sanctity, provoking grief, anger, and resistance in ‘Iwa and her community.

Dane’s journey illustrates the shift from an outsider’s admiration of Maui’s physical beauty to a deeper, more meaningful relationship with the land. Initially a thrill-seeker drawn to the island’s waves, he evolves into someone who begins to understand what true stewardship requires.

His willingness to assist ‘Iwa, to learn her customs, and to experience the land through her eyes marks a critical transformation. The story asserts that love for the land is not passive; it must be defended, embodied, and continuously recommitted to.

The threat of development, disrespect from tourists, and capitalist exploitation serve as antagonists not just to the environment but to a way of life that holds land as sacred. This theme challenges the reader to reexamine what it means to belong and to protect something that cannot speak for itself.

Healing through Love, Nature, and Self-Reckoning

Healing in The Maui Effect is never presented as linear or easy, and it is never confined to physical recovery. Both Dane and ‘Iwa are wounded in distinct ways—Dane by his brush with death and emotional stagnation, and ‘Iwa by grief over her mother’s death and the emotional armoring that loss brings.

The land itself, especially Maui’s forests and waterfalls, becomes a space where these characters confront and work through their pain. For ‘Iwa, the forest is a sanctuary of memory and connection, where signs from nature—like the pueo—act as spiritual guidance.

For Dane, the ocean transforms from an arena of conquest to one of reflection and vulnerability.

Their growing relationship facilitates another layer of healing, though it does not erase their wounds. Instead, love offers both characters the courage to confront themselves.

Dane learns to lower his emotional defenses and take responsibility for his choices, especially after his traumatic wipeout in Nazaré and the resulting physical paralysis. ‘Iwa, though hesitant, begins to explore the possibility of trusting again, of letting someone new into the private emotional space her mother once occupied.

The story does not suggest that love heals all, but rather that love, when grounded in respect and self-awareness, can become a powerful force for transformation. The emotional arc insists that true healing involves listening—to the land, to one’s body, to one’s history—and responding with care, humility, and persistence.

Fear, Ambition, and the Cost of Risk

Fear operates in The Maui Effect not just as a personal emotion but as a philosophical undercurrent tied to ambition and identity. Dane, as a big-wave surfer, lives with constant proximity to physical danger.

But the story makes clear that the more paralyzing fear is emotional—fear of inadequacy, of failure, of not being enough for the people one loves. His decision to surf Nazaré, despite promising to attend the fundraiser, reveals the pull of ambition and the internal conflicts that drive him.

That choice results in not just bodily harm but an emotional reckoning. It reveals how risk, while exhilarating, can also carry the price of missed opportunities and broken trust.

‘Fear’ also shapes ‘Iwa’s choices. Her resistance to Dane is not from lack of feeling but from fear of repeating emotional trauma.

Her guardedness is a protective mechanism forged by loss and disappointment. This theme interrogates the cultural glamorization of fearlessness, showing instead that bravery often means choosing to be present, to stay rather than run, to commit rather than retreat.

Dane’s eventual willingness to confront his emotional flaws and to paddle back into life—not just the waves—is the truest act of courage. The story argues that ambition without accountability can be destructive, but ambition tempered by empathy and reflection can lead to profound growth.

The ultimate question becomes not whether one should take risks, but what one is willing to sacrifice and who one is willing to become in the process.

Belonging, Identity, and Cultural Respect

Questions of who belongs, who gets to stay, and what it means to truly be part of a place run throughout The Maui Effect. ‘Iwa’s distrust of outsiders, especially mainlanders like Dane, is not irrational or prejudiced—it is rooted in a long history of cultural erasure, exploitation, and the dilution of Hawaiian traditions.

Her experiences with disrespectful tourists and opportunistic developers reflect the broader tensions between local communities and outsiders who seek paradise without understanding its price. Dane’s transformation from a transient surfer to someone seeking true connection is marked by his growing awareness of these dynamics.

Belonging is not granted freely; it is earned through listening, learning, and a willingness to change. Dane’s increasing respect for Hawaiian customs, his effort to engage with ‘Iwa’s conservation work, and his emotional openness signal a slow but meaningful shift toward cultural humility.

Yet even then, ‘Iwa reminds him that love alone does not equal belonging. Her insistence on boundaries and the final test of whether Dane can truly stay, not just physically but spiritually, adds complexity to the romance.

This theme underscores that cultural respect is not performative but involves sustained engagement, a relinquishing of entitlement, and a deep commitment to community values. Through these explorations, the novel asserts that identity and home are not merely inherited or claimed—they are continually shaped through action, empathy, and responsibility.

Grief, Memory, and Ancestral Connection

The presence of the past—especially in the form of familial loss and ancestral memory—is a quiet but potent force in The Maui Effect. ‘Iwa’s grief over her mother is not a subplot but a central element shaping her emotional life and choices.

Her memories of rituals, spiritual signs, and songs connect her to a lineage that continues to guide her, even in absence. This connection is more than symbolic; it infuses her actions with purpose and her resistance with sacred weight.

Her musical performance at the fundraiser, for instance, becomes not only an act of protest but a moment of communion—with her mother’s legacy, with her community, and with herself.

Dane, too, begins to understand the value of remembering. His emotional journey is marked by flashbacks, reflections, and moments of stillness where he contemplates his life’s direction.

His transformation is not simply catalyzed by falling in love, but by learning to integrate his past with his present—to accept where he has failed and to seek new meaning in connection. The book suggests that memory is not a static archive but a living force that can motivate, instruct, and even heal.

The ancestral elements—whether through natural symbols like the pueo or communal rituals—elevate the narrative beyond personal drama and into a broader reflection on lineage, loss, and the invisible threads that bind us to those who came before.

In the end, The Maui Effect becomes a tribute to memory as a compass—a guide not only through grief but toward a more meaningful life rooted in continuity, respect, and enduring love.