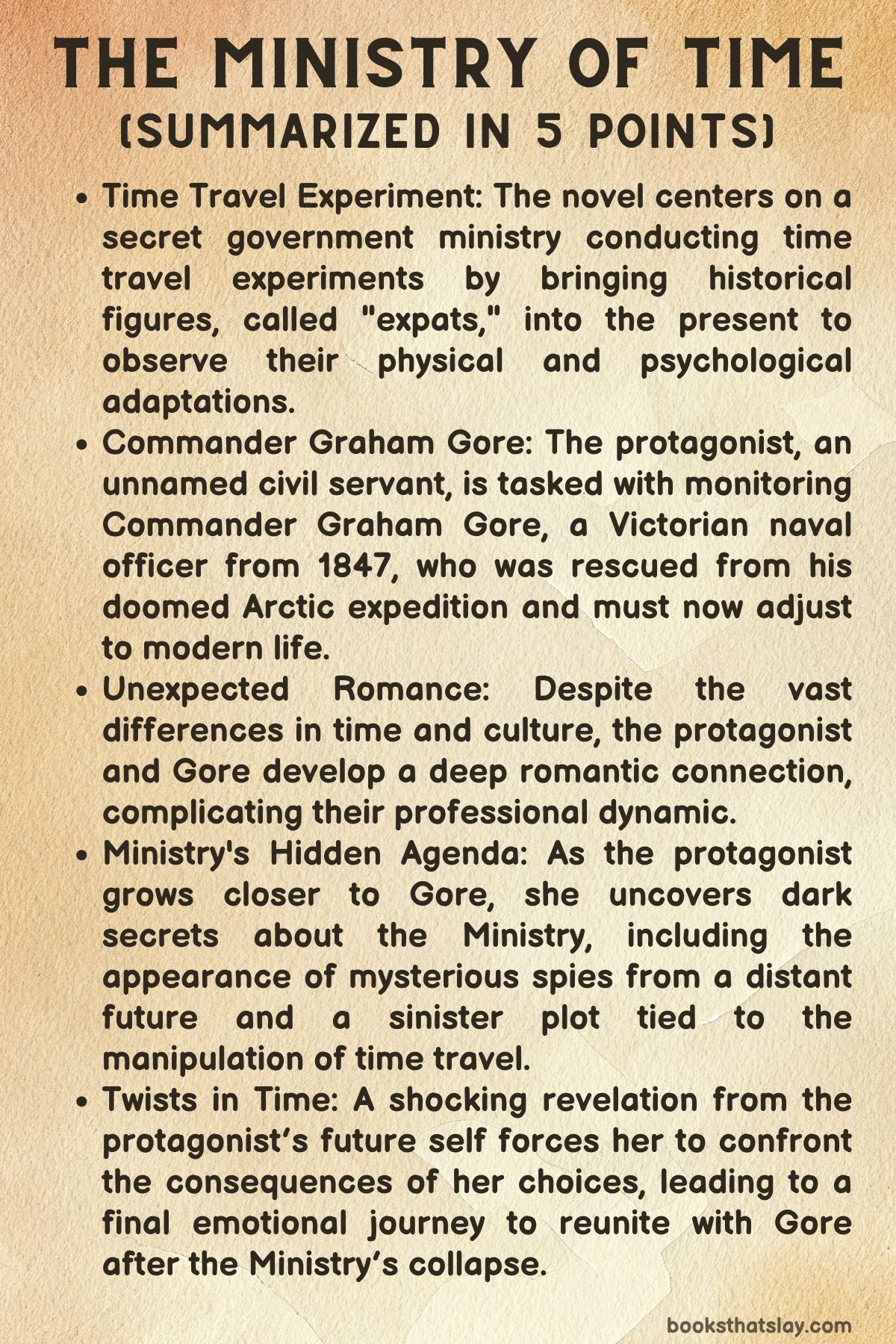

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley Summary, Characters and Themes

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley presents a tale centered around time travel, identity, and human relationships.

The story follows a unique protagonist who works as a “bridge” between the present and displaced individuals from different eras, helping them adjust to modern-day life. At the heart of the narrative is Commander Gore, a British naval officer from the Franklin Expedition of the 1800s, who is suddenly transported to the 21st century. As he struggles with the overwhelming changes in the world around him, his interactions with the protagonist reveal both personal and societal tensions.

Summary

The story of The Ministry of Time unfolds in a world where historical figures are mysteriously displaced through time and brought into the 21st century. These “expats” struggle to adapt to the modern world, facing profound disorientation and isolation as they try to make sense of technological advancements and societal shifts that are completely foreign to them.

The protagonist of the novel is tasked with assisting these expats as part of the Ministry of Expatriation, an organization that seeks to manage these displaced individuals. The protagonist’s role as a “bridge” is to help the expats transition into modern society without overwhelming them with too much information about the future.

At the heart of the novel is Commander Gore, a naval officer who once led an expedition in the 1800s. Gore, taken from the past after the tragic Franklin Expedition, finds himself in the present, utterly confused by the changes in the world around him.

The modern era confounds him. From the basic function of household appliances to the concept of personal hygiene, Gore’s disorientation highlights the alienation of the expats, who are all caught between two worlds: their past and the present.

The protagonist, who is of Cambodian descent, is tasked with guiding Gore through this bewildering new world. Their professional role requires them to remain neutral, but the relationship between them and Gore becomes fraught with tension.

The protagonist’s own struggles with identity—particularly as someone with a mixed-race background—complicate their work. Gore’s perceptions are influenced by his 19th-century worldview, including deeply ingrained racial attitudes that cause friction between the two.

While the protagonist is tasked with guiding Gore through his time dislocation, they also find themselves grappling with the complexities of their own identity, race relations, and personal history.

This dynamic forms one of the central emotional arcs of the story. As the protagonist works to help Gore adjust, they are forced to confront their own internalized biases, shaped in part by the trauma of their mother’s refugee background and their own history with the Cambodian genocide.

As the protagonist aids the displaced figures, the emotional cost of this work becomes evident, particularly as they are forced to confront the psychological toll these individuals carry with them. The expats, whose identities have been fractured by the violent tearing apart of their timelines, struggle to reconcile their pasts with their present selves.

Gore’s internal displacement mirrors the broader experience of many of the expats, who find themselves in a constant state of confusion and pain, unable to fully integrate into modern society. For Gore, this struggle is compounded by the haunting memories of his past.

His role as a commander, once in control of men in extreme circumstances, is now rendered useless in the face of his present circumstances. His deteriorating mental and physical state speaks to the toll that time travel takes on a person, making it a metaphor for the struggles of those displaced by war or other forms of violence.

The Ministry of Expatriation, however, operates with a cold, clinical efficiency that does not allow for the emotional nuances of the situation. The expats are treated as case studies, their progress measured in terms of adaptability and resilience.

The protagonist’s role within the Ministry is similarly impersonal, forced to balance the bureaucratic demands of the organization with the growing emotional connections they form with the expats, particularly Gore.

As Gore’s disorientation deepens, so too does the protagonist’s struggle with their role. The protagonist tries to maintain a professional distance but finds themselves increasingly invested in Gore’s wellbeing.

This growing emotional bond complicates their sense of duty, particularly as the Ministry’s detached surveillance methods become more invasive. The expats are monitored, their responses analyzed, and their progress treated like a scientific experiment.

The protagonist, though initially trained to avoid emotional entanglement, finds themselves questioning the ethics of the Ministry’s approach.

In parallel, the narrative explores the challenges the protagonist faces in modern society. The expats’ confusion over basic concepts, such as modern hygiene, personal freedoms, or even how to use a telephone, is both tragic and darkly humorous.

Gore, who once commanded a crew, now struggles with the basics of modern life. His confusion underscores the broader theme of alienation and isolation that runs through the narrative.

Even as he tries to adapt, his memories of the Franklin Expedition—where many of his comrades perished—remain a source of deep emotional pain. His experience highlights the tension between past and present, as well as the struggle for meaning in a world that no longer has a place for him.

The Ministry’s approach to the expats is scientific and detached. The expats’ struggles, including their fragmented identities, are treated as data points, and the Ministry’s goal is to integrate them into modern society as smoothly as possible.

But for the protagonist, the work becomes increasingly difficult. As their relationship with Gore deepens, they begin to understand that the expats’ disorientation is not just an issue of adjusting to new technologies, but a reflection of the larger, more painful issue of identity and belonging.

Throughout the story, the protagonist must come to terms with their own identity as they navigate the complexities of working with the expats. They are forced to confront their personal history, as well as the larger issues of race, displacement, and the emotional cost of helping others.

As they guide Gore and the other expats, they uncover more about themselves and the deep-seated issues that shape their relationship with these displaced individuals.

Ultimately, The Ministry of Time is a profound exploration of the intersection between personal history, identity, and the shifting forces of time. The expats’ journey is not just one of physical relocation, but of psychological and emotional upheaval.

Through their eyes, the protagonist comes to understand the larger forces at play—the trauma of history, the complications of modernity, and the deep isolation that comes from being torn from one’s time and place. As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that time travel is not just a matter of moving through eras, but of reconciling with the past and forging new connections in an ever-evolving present.

Characters

Graham Gore

Graham Gore is a British naval officer from the mid-1800s, and his character is central to the story. He is part of the time-travel project that brings historical figures into the present.

Once a confident and capable officer, Gore is now disoriented and emotionally broken due to the drastic changes he faces in the 21st century. His body, scarred by his past, particularly from a gunshot wound, serves as a symbol of his mental and physical decline.

Gore struggles with the shift from his previous life of adventure and leadership to a modern world he cannot comprehend. This sense of displacement is not just external, but deeply internal, as he contends with the psychological impact of being pulled out of his own time.

Despite this, he maintains an almost stoic façade, keeping his pain and confusion hidden. His relationship with the protagonist is marked by both affection and distance, as they try to navigate their different roles in the Ministry’s bureaucratic and often impersonal setup.

Gore’s inability to fully adapt to the 21st century, combined with his enduring melancholy, emphasizes the emotional cost of time travel and the alienation that comes with it.

The Protagonist

The protagonist is an unnamed translator working as a “bridge” for time-displaced individuals in the Ministry of Expatriation. With a complex background, they are of Cambodian descent, which adds layers of complexity to their identity, especially in the context of working with figures like Gore, who embody the deeply ingrained racial attitudes of their era.

The protagonist is caught in a delicate balance, as they navigate the expectations of their role while struggling with their personal history, particularly the trauma inherited from their mother’s refugee background during the Cambodian genocide. They serve as a guide for the expats, helping them adapt to modern life, but this professional task is complicated by their own emotional and cultural struggles.

Over time, their connection to Gore deepens, though it is marred by moments of confusion and frustration. As the protagonist becomes increasingly involved in the Ministry’s operations, they question the ethics of their work, especially as they uncover the darker aspects of the project.

Their emotional journey is a constant push-pull between personal involvement and the cold, clinical demands of their role. In the end, the protagonist must confront their own identity and the consequences of their participation in a morally ambiguous world.

Margaret Kemble (Sixteen-sixty-five)

Margaret Kemble is another important expat from the past who becomes entangled in the complex dynamics of the Ministry’s operations. Like Gore, Margaret finds herself torn between the modern world and the life she once knew.

Her character represents the broader theme of the struggle for identity when thrust into a time and place that feels foreign and often hostile. Margaret’s interactions with other expats, particularly with Gore, provide insight into the emotional toll of time travel.

Despite her own struggles, she embodies a certain resilience, as she, like the others, attempts to carve out a sense of self in an environment that does not understand or appreciate her history. Margaret’s presence in the narrative highlights the tension between the personal and the political, as she is caught in the Ministry’s experiments and the larger web of control, surveillance, and manipulation that defines the story’s world.

Arthur

Arthur is a quirky companion to Margaret and an ally to the protagonist. His character offers a contrast to the intense emotional and political undertones of the story.

Though his role in the narrative is not as prominent as others, Arthur’s personality serves as a much-needed relief from the heavy themes surrounding betrayal, time manipulation, and the Ministry’s cold bureaucracy. His interactions with the protagonist and Margaret reveal a simpler, more grounded aspect of human connection.

However, as the story progresses and the stakes rise, Arthur’s fate takes a tragic turn, which underscores the moral complexities of the world they inhabit. His death serves as a turning point for the protagonist, propelling them deeper into the dark and dangerous realities of the time-travel project.

Vice Secretary Adela

Adela is a key figure within the Ministry, and her role is central to the bureaucratic and often ruthless nature of the organization. She serves as a mentor to the protagonist but also represents the moral ambiguity and the cold, clinical detachment that defines the Ministry’s approach to the expats.

Her warnings about a mole within the organization and the threat of betrayal set the stage for the protagonist’s growing disillusionment with the Ministry’s operations. Adela’s true motivations and actions are gradually revealed as the protagonist uncovers disturbing truths about the Ministry’s methods and its handling of the time-travel project.

Her character serves as a reminder of the dangers of power and control, particularly when wielded by institutions that prioritize their objectives over the well-being of individuals.

Simellia

Simellia initially appears to be an ally of the protagonist, offering support and camaraderie within the Ministry. However, her character is eventually revealed to be a traitor, working for the forces of the future with motives rooted in survival and self-interest.

Her betrayal is emblematic of the larger theme of loyalty, manipulation, and survival in a world where time itself is a tool for control. Simellia’s actions raise questions about the ethics of the time-travel project and the moral compromises individuals are willing to make when faced with difficult circumstances.

Her character arc is a tragic one, as she embodies the harsh realities of a future where personal connections are fleeting, and the stakes of betrayal are high. Through her, the narrative delves into the darker aspects of time travel, where the pursuit of control can lead to devastating consequences for those caught in its web.

Themes

Time and Displacement

Time, in The Ministry of Time, serves as both a literal and metaphorical force that deeply influences the characters and their actions. The narrative’s central motif revolves around time travel and its disruptive impact on the individuals who experience it.

The expats, including Graham Gore, are pulled from their historical contexts and placed in a future that feels alien to them. Gore, a British naval officer from the mid-1800s, represents the primary example of this dislocation.

His inability to comprehend the modern world—ranging from basic household appliances to social norms—demonstrates the overwhelming sense of alienation that comes with displacement. The time traveler’s experience isn’t just one of physical displacement but psychological dislocation, as the expats are forced to reconcile with the loss of their original identity and the need to adapt to a new time.

This transformation involves both a literal adjustment to new technologies and a more profound struggle with the mental toll of abandoning one’s familiar world. The concept of time travel, therefore, is depicted not merely as a fantastical element, but as a vehicle for exploring how people react to the profound alienation caused by being removed from everything that forms their identity, their past, and their sense of belonging.

For the protagonist, who works as a “bridge” between these displaced individuals and the present, time itself becomes a source of personal conflict as they navigate the moral and emotional weight of guiding others through their traumatic dislocations.

Identity and Self-Discovery

The theme of identity is intricately explored through the lens of both the expats and the protagonist, highlighting how individual histories and personal connections shape the experience of time travel. The protagonist, of Cambodian descent and raised in the shadow of their mother’s traumatic refugee experience, grapples with their own fractured identity.

Their professional role in the Ministry requires them to help others adjust to the future, but they struggle with their own sense of belonging, compounded by their mixed-race background. The dissonance between their professional role and personal history becomes increasingly significant as they interact with Gore and the other expats.

The racial tensions that arise between them and Gore underscore the broader cultural divides and inherited prejudices that continue to shape interactions. Gore, although a victim of his own time’s rigid social norms, clings to ideas about race and class that clash with the protagonist’s modern sensibilities.

This tension is not just personal but emblematic of the larger cultural and historical forces that continue to shape identity, even when removed from their original contexts. The protagonist’s emotional connection to Gore further complicates this identity struggle, as they attempt to reconcile their professional duties with their desire for genuine human connection.

This theme ultimately raises larger philosophical questions about what it means to belong and how one’s sense of self is continually negotiated in the face of history and change.

Isolation and Connection

The experience of isolation is a pervasive theme throughout The Ministry of Time, portrayed both through the dislocation of time and the emotional detachment required by the Ministry’s bureaucratic nature. While time travel physically transports individuals into an unfamiliar future, the psychological isolation felt by the expats is even more profound.

Gore’s disorientation in the 21st century, juxtaposed with his memories of the Franklin Expedition, reflects not just the alienation caused by temporal displacement but the emotional void that comes with being separated from one’s past and comrades. The expats, though surrounded by others, are emotionally adrift, tethered to a past that no longer exists, while also being unable to fully integrate into the present.

This sense of disconnection is mirrored in the protagonist’s role within the Ministry. Despite being tasked with helping the expats adjust, the protagonist is forced to suppress empathy in order to perform their job effectively, leading to their own emotional isolation.

The Ministry’s cold, clinical approach to the expats, treating them like subjects of an experiment rather than human beings in need of care, amplifies this theme of isolation. However, despite the Ministry’s dehumanizing tactics, the protagonist forms emotional bonds with individuals like Gore, complicating their professional detachment.

Their fragile intimacy—marked by moments of awkward affection and unspoken longing—illustrates the deep human need for connection, even in the most disorienting and isolating circumstances. The story thus examines how connection is often hindered by the weight of history, the institutional demands of bureaucracy, and the deeply ingrained emotional scars of past traumas.

The Ethics of Time Travel and Manipulation

The narrative also explores the moral ambiguities inherent in time travel, particularly when used as a tool of control and surveillance. The Ministry’s role in monitoring and studying the expats mirrors broader themes of power, ethics, and exploitation.

The expats, despite being displaced individuals, are treated as experiments—studied, tested, and observed through invasive methods meant to gauge their adaptability. This scientific, detached treatment of human beings raises questions about the ethics of such an approach.

The protagonist’s growing unease with the Ministry’s treatment of the expats highlights the tension between professional duty and personal morality. While the protagonist begins with a clear sense of professional responsibility, their increasing involvement with the expats, particularly Gore, leads them to question the larger implications of their work.

This moral dissonance is further complicated by the Ministry’s covert operations, where power is wielded not just through time travel but also through manipulation of information and identities. The bureaucratic surveillance that characterizes the Ministry’s methods is presented as a form of control that strips individuals of their autonomy and sense of self.

As the protagonist uncovers the darker purposes behind the time-travel project, including the manipulation of history, they are forced to confront the ethical implications of altering time and shaping the course of history for political or personal gain. This exploration of power and control underscores the dangers of unchecked authority and the potentially catastrophic consequences of tampering with the past and future.

The Human Cost of Progress

Ultimately, The Ministry of Time presents a sobering reflection on the human cost of technological and societal progress. The narrative critiques the relentless forward march of time and the technological advancements that come with it, particularly in the way these changes affect individuals who are unable or unwilling to adapt.

The expats, particularly Gore, are symbols of a world that is rapidly passing them by. Gore’s deep longing for a simpler, more tangible existence in contrast to the complexities of modern life illustrates the psychological toll that progress can take on those who are displaced by it.

The novel portrays modernity not as a utopian ideal but as a complex, often alienating force that creates divisions between individuals, cultures, and eras. The protagonist’s own struggle to reconcile their professional obligations with their deeply held beliefs about empathy and human connection highlights the cost of living in a world where personal histories are overshadowed by the demands of modern systems.

The emotional and psychological toll on the characters—whether through the dislocation of time or the institutional pressures of the Ministry—underscores the fragile nature of human identity in a world where progress often seems indifferent to the well-being of individuals. Through these experiences, the story suggests that while progress may offer new opportunities, it also demands a sacrifice of personal connection, history, and identity.