The Mostly True Story of Tanner & Louise Summary, Characters and Themes

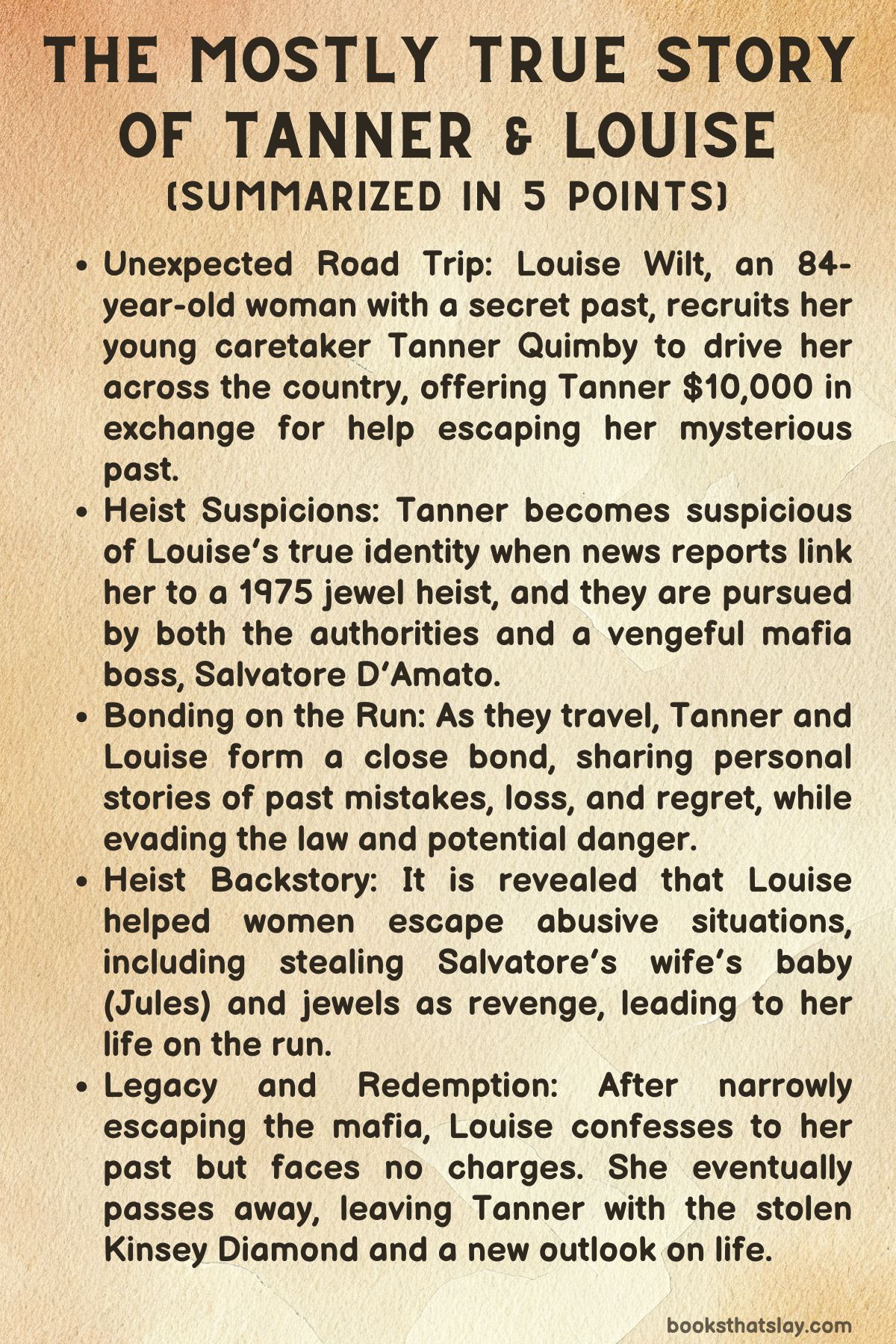

The Mostly True Story of Tanner & Louise by Colleen Oakley is a charming heist novel that blends humor, heart, and a dash of adventure. Released in 2023, the book follows the unexpected bond between 84-year-old Louise Wilt and her 21-year-old caregiver, Tanner Quimby.

Both women are dealing with their own set of life challenges—Louise with a past filled with secrets and Tanner with a stalled future—when they embark on a cross-country road trip. Along the way, they find themselves on the run from the law, mafia hitmen, and their own histories, all while redefining what it means to have second chances.

Summary

Louise Wilt’s daughter, Jules, becomes alarmed when she can’t contact her 84-year-old mother for days and alerts the police in Atlanta.

But ten days earlier, Louise had received a troubling letter from someone named George Dixon, prompting her to consider running away.

Meanwhile, Tanner Quimby, a college dropout struggling with the aftermath of a devastating injury, arrives as Louise’s caretaker. After an awkward start, they settle into an uneasy routine, with Tanner gaming for hours while Louise grapples with her secret past.

Louise’s neighbor August fixes her car and flirts with Tanner, but their budding connection fizzles when he stands her up for a date.

As Tanner hears local rumors about Louise’s criminal past, she stumbles upon a news report about a 1975 heist where jewels were stolen.

The main suspect, a woman named Patricia Nichols, looks alarmingly like Louise. Though Tanner tries to brush off the resemblance, her suspicions grow.

Things take a sharp turn when Louise enlists Tanner as her getaway driver, offering to pay her $10,000—the exact amount Tanner needs to return to college.

They hit the road in a hidden Jaguar stashed in Louise’s shed, heading west as police begin to suspect that Louise may be the fugitive Patricia Nichols.

Along the way, Tanner and Louise start to bond, and Tanner reveals painful memories, including her shattered soccer career and the guilt she carries over betraying her best friend, Vee.

The FBI, led by Special Agent Lorna Huang, connects Louise to the 1975 heist and pursues the pair. Louise, determined to reach George before it’s too late, grows increasingly anxious, while Tanner’s commitment to their journey solidifies.

In St. Louis, they face car trouble, leading to a brief stopover and a deeper conversation about their lives. Louise opens up about her time in jail, and Tanner learns to shoot a gun under Louise’s tutelage.

In Colorado, August reappears to help them reach California, where they break George out of a senior living facility.

But Salvatore D’Amato, the mafia boss Louise betrayed decades earlier, is waiting for them. In a tense showdown, Tanner fires a warning shot just as the FBI arrives.

The truth unfolds: Louise had been part of a secret network helping abused women, including Salvatore’s wife, Betsy.

After Betsy’s death, Louise rescued her baby—Jules—and also stole jewels from Salvatore. Though Louise confesses to stealing Jules, the authorities decide not to press charges for the heist.

Tanner, now empowered by their journey, chooses to live life on her own terms. When Louise dies, Tanner inherits a surprise gift—the infamous Kinsey Diamond—and a new chapter begins for her.

Characters

Tanner Quimby

Tanner Quimby, a former college soccer player, is a young woman in her early twenties who feels lost and disillusioned with life. Her promising athletic career at Northwestern ended abruptly after she fractured her leg in a fall from a fraternity house balcony, leaving her bitter and angry.

This injury not only cost her the opportunity to continue playing soccer but also deprived her of the scholarship that was her financial lifeline, leaving her unable to afford tuition. Tanner’s sense of failure is compounded by the fractured relationship with her family, particularly her mother, who has grown frustrated with her attitude and coping mechanisms.

Tanner’s emotional state is defined by her resentment toward life, manifested in her excessive video game playing, which she uses as an escape from reality. Initially, Tanner appears withdrawn, sarcastic, and uninterested in forging connections, especially with Louise, whom she views as just a job.

However, as the story progresses, Tanner evolves from a passive and embittered character into a more engaged and empathetic person. Louise’s influence helps Tanner confront the deeper issues beneath her anger, including her fractured friendships, the unresolved guilt she feels for reporting her friend Vee’s drug use, and her fear of failure.

Tanner’s journey is one of emotional maturity, learning to open up and care for others, and ultimately, rediscovering her own agency and strength. By the end of the novel, Tanner has not only rebuilt her relationships with her family and Vee but has also forged a deep bond with Louise.

Through their adventures, Tanner’s bitterness gives way to a more hopeful outlook, and she embraces the idea of a future that is not defined by her past failures.

Louise Wilt (Patricia Nichols)

Louise Wilt, an 84-year-old woman, is a complex character with a mysterious past. Known initially to Tanner and others as a frail, elderly woman recovering from a hip injury, Louise is later revealed to be Patricia Nichols, a woman with a complicated and morally ambiguous history involving a heist and ties to the mafia.

Louise’s backstory is marked by her role in a 1975 jewel heist, but her motives were far more noble than they initially appeared. Alongside her best friend, George, Louise helped women escape abusive relationships, running a kind of underground network.

Her criminal activities, including the heist, were intertwined with her efforts to protect others, particularly Jules, the child of an abused woman named Betsy. Louise’s decision to steal both the jewels and Jules from the violent mafia boss Salvatore D’Amato demonstrates her resourcefulness, bravery, and deep sense of justice.

Despite her criminal past, Louise is portrayed as a deeply moral person who has always been motivated by the desire to help vulnerable women. Her relationship with Tanner allows her to impart wisdom gained from her long, eventful life.

Louise’s character reflects a complex mix of regret and pride—regret for some of the choices she made, especially regarding Jules, but also pride in her role as a protector of those who needed help. Louise’s battle with Parkinson’s disease adds another layer to her character, showing her vulnerability and humanity.

She is a woman who has spent her life fighting—both for others and for herself—but who, in her final days, is ready to confront the truth of her past. Her bond with Tanner becomes central to her later life, as Tanner becomes not only her caretaker but also her confidante and co-conspirator.

Louise’s final gesture of passing the Kinsey Diamond to Tanner is symbolic of her passing on her legacy, trusting Tanner to navigate her own moral choices.

George Dixon

George Dixon is Louise’s longtime friend and partner in both crime and their efforts to help women escape abusive relationships. George’s character is revealed gradually throughout the novel, but when she appears in the present timeline, she is living in a senior care facility, hiding from her past.

George’s loyalty to Louise is central to her character; even though they were separated for many years after the heist, their bond remained strong. George’s relationship with Louise is one of deep trust and camaraderie, and their reunion in the novel highlights the strength of their friendship.

George’s decision to forgive Louise for her past actions, including their involvement in the heist and the consequences that followed, shows her generosity and the depth of her affection for her friend. George’s role in the story also emphasizes the theme of female solidarity, as she and Louise, throughout their lives, worked together to save women from abusive situations.

Jules Wilt

Jules Wilt is Louise’s daughter, though unbeknownst to her, she was stolen as a baby by Louise (then Patricia Nichols) after her biological mother, Betsy, died at the hands of Salvatore D’Amato. Jules represents the life Louise built after the heist, a life filled with both deception and love.

Though Louise’s actions were morally questionable, she raised Jules as her own, giving her a life away from the violence of her biological father. Jules, throughout most of the novel, is unaware of her true parentage, and her concern for her missing mother motivates her to involve the police, which inadvertently propels the authorities to pursue Louise and Tanner.

Despite being kept in the dark about Louise’s past, Jules’s love for her mother is genuine, though her character also highlights the theme of secrets within families. Her arc ends without her learning the full truth, but this ignorance is framed as protective, allowing her to maintain the simpler, loving image of her mother.

August

August, Louise’s neighbor, plays a relatively minor but important role in the novel as Tanner’s potential love interest and as a driver who helps Louise and Tanner in their final push toward California. August is initially presented as a flirtatious and handsome young man, who piques Tanner’s interest.

However, his importance grows as he proves to be reliable and willing to assist the duo in their escape, despite the potential dangers involved. August’s relationship with Tanner adds a layer of romance to the plot, and their developing connection reflects Tanner’s growth throughout the story.

His role also offers some lighthearted moments, balancing the tension of the heist plot with personal and emotional dynamics. August’s presence underscores the theme of trust and loyalty, as he comes through for Tanner and Louise when they need him most.

Salvatore D’Amato

Salvatore D’Amato is the novel’s antagonist, a mafia boss whose abusive behavior toward his wife, Betsy, sets the central events of the story in motion. Salvatore represents the violent, oppressive forces from which Louise and George sought to protect women.

His abuse led to Betsy’s death and spurred Louise to steal both his child, Jules, and his jewels as an act of revenge and justice. Throughout the novel, Salvatore looms as a menacing figure, even in his absence, as Louise fears his potential retribution.

His final appearance in the story, confronting Louise and George in the motel, showcases his vengeful and dangerous nature. However, his confrontation with Tanner, who bravely attempts to defend Louise, symbolizes the new generation standing up to the old forces of violence and control.

Salvatore’s character serves as a catalyst for the plot, but he is also a symbol of the dangers that Louise spent her life fighting against.

Special Agent Lorna Huang

Special Agent Lorna Huang is the FBI agent tasked with investigating the cold case surrounding the 1975 Kinsey Diamond heist. Lorna represents the law and order element of the story, as she relentlessly pursues the truth about Patricia Nichols and the heist.

Though her role is primarily that of an investigator, she is a key player in driving the plot forward, as her investigation eventually catches up with Louise and Tanner. Lorna’s character is persistent and dedicated to her job, and she serves as a counterbalance to the morally gray actions of Louise and Tanner.

However, her pursuit of justice is nuanced, as she is shown to be respectful and professional, focusing on the truth rather than personal vendettas. Her presence in the novel highlights the theme of justice and how it can be interpreted differently by different characters.

Themes

The Complexity of Identity and Reinvention in Response to Trauma

In The Mostly True Story of Tanner & Louise, Colleen Oakley delves deeply into the theme of identity and its fluidity, particularly in how characters respond to trauma. Louise Wilt, or rather Patricia Nichols, exemplifies how individuals might reinvent themselves after traumatic experiences.

Louise’s shift from a young woman helping others escape abusive situations through a whisper network, to a jewel thief, and ultimately to a quiet elderly woman struggling with Parkinson’s disease, represents multiple layers of identity forged by both personal decisions and the need for survival. Her transformation is not merely a series of name changes, but a complex reaction to the emotional, moral, and physical violence she endures and witnesses.

Trauma pushes her to live multiple lives, blurring the lines between her true self and her adopted identities. This theme of identity extends to Tanner as well, who is also in a state of emotional and personal flux.

Her identity crisis stems from the end of her soccer career and her subsequent feelings of worthlessness. Tanner’s fall from grace, caused by her inability to set boundaries with a pushy frat boy, leaves her struggling with a deep-seated sense of shame and regret.

Much like Louise, she is in a phase of reinvention, attempting to figure out who she is without her athletic achievements. Louise’s guidance helps Tanner understand that identity is not a fixed construct, but something that can be molded through choices—whether moral or immoral.

Thus, both women’s journeys demonstrate how identity is a dynamic concept, shaped by personal trauma and external pressures, but also by the willingness to change and adapt.

Intergenerational Female Bonding as a Path to Emotional Healing and Growth

The novel explores intergenerational female relationships as vital sources of emotional support and healing. The relationship between Tanner and Louise, two women separated by decades of experience and life circumstances, becomes central to their personal growth.

Initially, their bond is transactional—Tanner needs money, and Louise needs a caretaker. However, as their journey progresses, it evolves into a complex emotional connection. Louise, despite her elderly age and fragile condition, becomes a mentor figure to Tanner, imparting wisdom about anger, fear, and resilience.

Louise’s advice—that women who aren’t angry aren’t paying attention—reflects her own lived experience of fighting back against societal oppression, abusive men, and a life of hiding her true identity. Through her guidance, Tanner learns to confront her own anger and feelings of brokenness, which stem from both her physical injury and her unresolved guilt over betraying her friend, Vee.

This theme of female bonding extends beyond just Tanner and Louise, touching on the relationship between Louise and her old friend, George. Louise’s reunion with George, a woman who played a key role in her past life and helped her during the jewel heist, reaffirms the idea that women’s bonds—particularly those forged in difficult, traumatic circumstances—can be both healing and redemptive.

These friendships offer emotional refuge in a world filled with betrayal, disappointment, and violence, especially at the hands of men like Salvatore. Oakley suggests that intergenerational female relationships can act as lifelines for women in moments of crisis, providing not only practical assistance but also emotional guidance and healing.

The Moral Ambiguity of Crime and Justice in the Context of Oppressive Systems

Oakley’s novel explores the moral ambiguity of crime, especially when it is committed in the context of resisting oppressive systems, such as domestic abuse or patriarchal control. Louise’s life of crime, beginning with her involvement in mail theft and culminating in the infamous jewel heist, is framed not as an act of greed or maliciousness but as a response to systemic injustice.

Her stealing of the Kinsey Diamond, while technically illegal, is rooted in a moral stance—protecting a child, Jules, from an abusive father, Salvatore D’Amato. Louise’s actions challenge the black-and-white morality typically associated with crime, suggesting that sometimes, unlawful actions are necessary to resist corrupt or violent systems.

Moreover, the justice system itself is shown to be flawed. While the FBI hunts Louise down for her past crimes, it is clear that they have missed the true moral weight of the situation—Louise’s crimes were committed to protect and save lives, not to harm others.

The legal system, in this context, is blind to the emotional and moral complexities underlying the case. Even when Louise is confronted by Salvatore in the present day, the threat he poses to her and George’s safety once again justifies Tanner’s attempt to shoot him, even though she fails.

Oakley uses these scenarios to question whether the concept of justice is always aligned with legality, and whether the laws themselves are equipped to deal with situations where crimes are committed in the pursuit of a greater moral good.

The Tension Between Personal Freedom and Responsibility in Cross-Generational Relationships

In The Mostly True Story of Tanner & Louise, Oakley explores the delicate balance between personal freedom and responsibility, particularly in relationships between different generations. At the outset, both Tanner and Louise are burdened by the expectations placed upon them by their respective families.

Louise, recovering from a broken hip, is forced into a situation where her children insist she have a caretaker, despite her desire to remain independent. Tanner, similarly, is under pressure from her parents and her past as a promising athlete to live up to certain expectations, yet her injury has left her questioning what direction her life should take.

Both characters grapple with the loss of freedom that comes with age, injury, and societal roles. As the story unfolds, the tension between freedom and responsibility shifts. While initially resentful of the caregiving role she’s forced into, Tanner begins to appreciate her responsibility toward Louise, seeing it not as a constraint on her personal freedom but as a source of purpose.

Louise, in turn, becomes responsible for Tanner in a different way, offering her the emotional tools to deal with life’s hardships and providing her with a financial lifeline to regain her independence.

Their journey across the country symbolizes not just a physical escape but an exploration of what it means to be free—free from societal expectations, family obligations, and the burdens of past mistakes.

Oakley suggests that true freedom is not the absence of responsibility, but rather the conscious decision to take responsibility for oneself and others, especially across generational divides.