The Nanny’s Handbook to Magic and Managing Difficult Dukes Summary, Characters and Themes

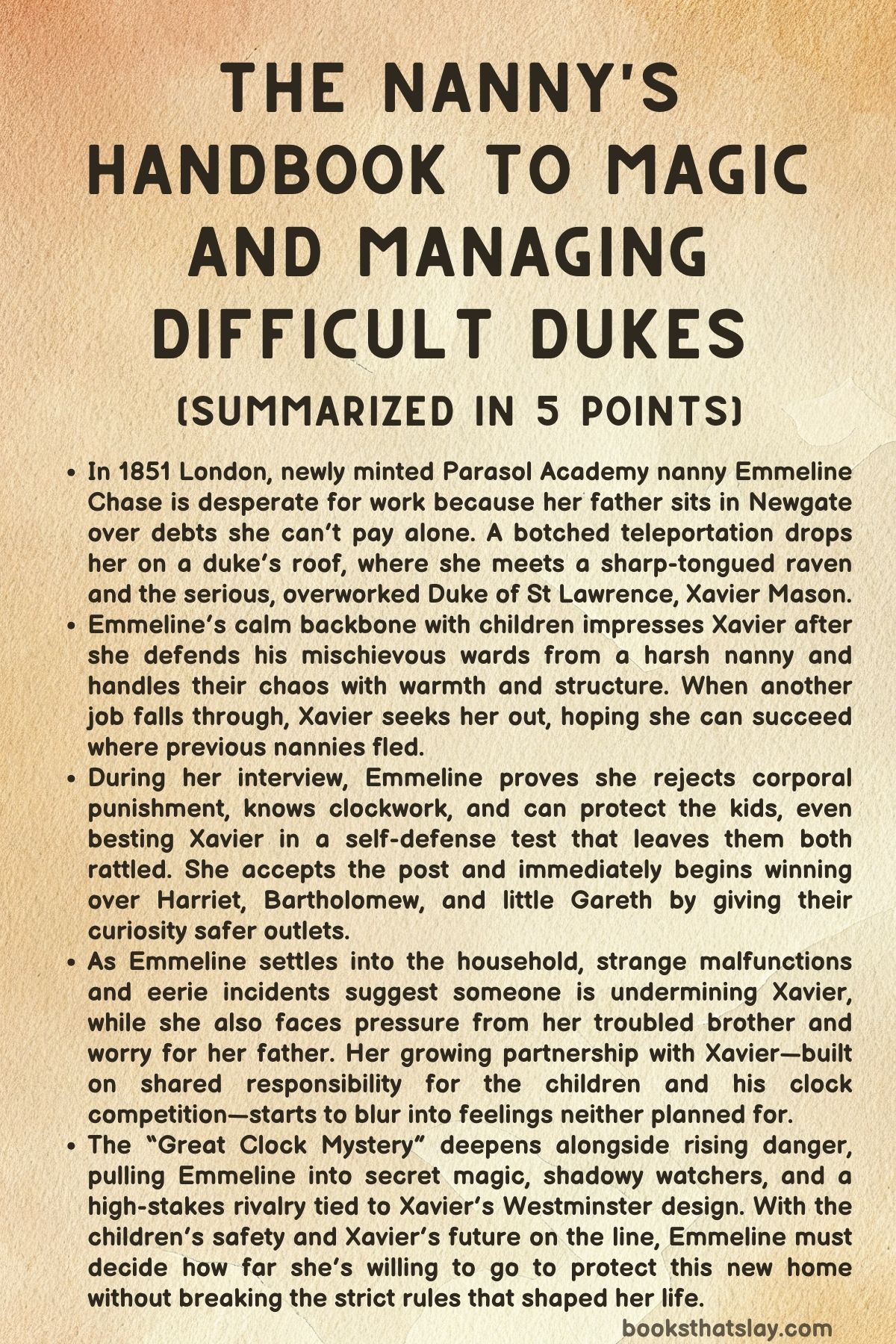

The Nanny’s Handbook to Magic and Managing Difficult Dukes by Amy Rose Bennett is a historical fantasy romance set in Victorian London, where good manners and secret magic coexist behind polite society’s curtains. The story follows Emmeline Chase, a newly trained Parasol Academy nanny whose education includes discreet spells, self-defense, and absolute devotion to children’s welfare.

Sent to a troubled noble household, she meets the brilliant but overwhelmed Duke of St Lawrence and his unruly orphaned wards. As Emmeline tries to steady the home and protect it from mysterious sabotage, attraction grows between nanny and duke—testing rules, class boundaries, and their own guarded hearts.

Summary

Emmeline Chase is twenty-five, freshly graduated from the Parasol Academy, and terrified that she will not succeed in her first real post. The Academy demands perfection in etiquette as much as in covert magical practice, and Emmeline’s nerves show when she spills tea and blurts an oath at luncheon.

She has more to fear than embarrassment: her father sits in Newgate prison for debt, and Emmeline’s wages are the only thing keeping him fed and sheltered. Her late husband wasted their funds, her brother is unreliable, and the clock is ticking on her father’s survival.

The headmistress, Mrs. Felicity Temple, gentler than Emmeline expects, cleans her pinafore with a whispered spell and sends her to an interview by leyporting—teleportation along hidden Fae leylines.

Emmeline opens a portal in the dorm wardrobe, focuses on her destination, and steps through. Something goes wrong.

Instead of arriving inside a Metropolitan Police box at Bedford Square, she appears on a slick rooftop in Belgrave Square, four stories above the street, rain threatening, no easy way down.

Desperate, Emmeline calls for help and hears an elegant voice in her mind. A raven introduces himself as Horatio Ravenscar and is delighted to find a human who can speak telepathically with animals.

He flies off to fetch his master, Xavier Mason, seventh Duke of St Lawrence. Xavier, a serious horologist racing to complete a grand clock design, is startled to see a woman stranded on his roof.

He guides her to a hidden trapdoor terrace and climbs up to rescue her. On the way down she slips, lands in his arms, and they both end up flustered and laughing in the attic.

Their awkward meeting is interrupted by chaos in the nursery. Harriet Mason—called Harry—has shocked the current nanny by producing her pet frog, Archimedes.

The nanny, Snodgrass, declares Harry wicked and demands punishment. Emmeline steps in without thinking, insisting the child is not wicked and refusing to accept harsh discipline.

Xavier calms things, promising a proper aquarium so the frog stays safe from both staff and Horatio. Emmeline also returns a tin soldier she found on the roof, which belongs to the youngest boy, Gareth.

Before leaving, she hands Xavier her Parasol Academy card, suggesting he contact the headmistress if he needs a new nanny. She walks into the rain, unaware that Xavier is already hoping she will return.

The next day Emmeline learns the Culpeppers have rejected her. Then Mrs.

Temple reveals a surprise: the Duke of St Lawrence has come to the Academy and requested Emmeline by name. Emmeline quickly agrees to interview.

Her second leyport brings her to Belgrave Square properly, though an unknowing constable nearly arrests her. She uses a mild umbrella spell to confuse him and escapes with dignity intact.

At St Lawrence House, Horatio greets her mind-to-mind and reports that Snodgrass has been dismissed after threatening birch punishment. In Xavier’s study, the interview begins stiffly but warms as Emmeline answers with honest conviction.

When asked about corporal punishment, she rejects it outright, explaining the Academy’s rules and her belief that children need guidance, safety, and respect. Xavier explains his three wards—Harry, Bartholomew, and Gareth—were orphaned in a yachting accident and have chased away every nanny since.

He also admits something darker: his household has suffered strange mishaps, his clocks won’t keep time, servants keep quitting, and a smartly dressed stranger has followed him at night. As he competes for a prestigious Westminster clock commission, he fears sabotage and wants someone able to protect his children.

Emmeline surprises him with her competence. She knows antique clocks from her father’s old shop and even enjoys auctions.

When Xavier asks whether she can defend herself, she offers a demonstration. He grips her wrist; she twists free.

He grabs again and she locks him into a hold that drives him to a knee. When he tries a chokehold from behind, she flips him over her hip.

They crash into the tea table, end up tangled on the rug, and stare at each other in breathless embarrassment. Xavier, shaken but impressed, hires her on the spot.

Almost immediately, another disaster erupts: Harry has tried to create a ginger-beer fountain for her brothers, and the bottle has exploded, coating furniture and priceless books in sticky foam. Xavier scolds Harry for endangering everyone.

Emmeline kneels with the girl, admits her own foolish rooftop mistake, and gains Harry’s trust by treating her as clever rather than bad. To redirect her energy, Emmeline proposes an investigation: together they will monitor every clock in the house to solve the “Great Clock Mystery.” Harry is fascinated and agrees.

Once the children leave, Emmeline quietly uses rare calamity magic—decalamitifying dust—to restore the library. Bartholomew wanders back in, sees her kindness, and admits he misses his parents and wants hugs.

Emmeline comforts him, and her pockets produce a tiny terrapin and a jar of crickets, charming him completely. She begins to bond with the wards not by taming them, but by understanding their grief and curiosity.

Over the next weeks Emmeline settles into the role. A museum outing becomes another test when Bartholomew finds what he thinks is a beetle—a priceless Egyptian scarab artifact.

A guard accuses Emmeline of theft and demands she empty her pockets. Protecting her reputation and the Academy’s secrecy, she uses a subtle memory-fogging perfume, replaces the scarab, and steers the children away before trouble spreads.

Xavier arrives to join the excursion, praises her work, and introduces her to his arrogant rival Sir Randolph Redvers. Randolph flirts openly with Emmeline and insults Xavier’s horological expertise.

Xavier cuts him down coolly and shepherds his household to safety, the tension between duke and rival sharpening Emmeline’s sense that danger is real.

Outside St Paul’s, Emmeline’s brother Freddy confronts her, frantic over debts and blaming her for not rescuing the family faster. Xavier appears, pins Freddy with a rapier, and forces an apology.

Later, over drinks, Emmeline explains her father’s imprisonment and Freddy’s failing music hall. Xavier promises her job is secure and that he values her.

On their walk home they notice two thugs trailing them. Emmeline hides them with a concealment spell under her umbrella.

The men grumble about losing “Lunatic St Lawrence” and report they’ve frightened him for their employer. The close call and cramped hiding place ignite a rush of feeling; Emmeline and Xavier kiss, then recoil, agreeing it cannot happen again.

Xavier soon deepens his support by paying Emmeline’s father’s debt, securing his release, and offering him work as a horology assistant. Emmeline is grateful but determined not to let gratitude blur boundaries.

Still, the clocks remain erratic until Emmeline discovers a new synchronization spell mysteriously appearing in her Academy handbook. She aligns the household timepieces to Greenwich Time.

When Xavier finds her in his study late at night, their restraint fails. They share another kiss that becomes a secret night together, honest and tender, with Emmeline guiding the inexperienced duke.

Immediately afterward, the gaslights across the house flicker out again, a chilling reminder that sabotage continues.

May brings the Great Exhibition at Hyde Park. Xavier presents his dazzling “Queen of Clocks” at the Crystal Palace, and the family tours marvels of engineering and science.

Randolph mocks Xavier’s invention, but high authorities praise it, hinting at a medal. Emmeline manages the excited children in the crowd while Xavier fights to keep focus on his commission—and on the woman who has quietly become the center of his world.

Back at St Lawrence House, Xavier reveals his “King of Clocks” design for Westminster and finally speaks plainly: he loves Emmeline and wants to marry her. She admits she loves him too and accepts.

That night they celebrate in secret, and Emmeline burns her nanny’s cap, choosing a new life.

Before dawn Horatio detects smoke. The house is on fire.

Xavier insists Emmeline leyport outside, but she refuses to leave him. They race through a hidden passage to save the clock plans.

In the study they find the culprits: Sir Randolph Redvers and Xavier’s cousin Algernon. They confess to bribing servants, spreading rumors that Xavier is mad, and wrecking his clocks to ruin his chances.

Algernon wants the dukedom; Randolph wants the commission. They steal the plans, tie Xavier and Emmeline to columns, and leave them for the flames.

Emmeline slips her bonds, uses a concealed dagger, and frees Xavier. She calls on Fae aid and receives decalamitifying dust again.

Together they rush into the burning hall, cast the spell, and the fire vanishes as if it never existed. They leyport outside to stunned servants and police.

Horatio spots the villains nearby. Xavier knocks them down, retrieves his plans, and the constable arrests them for arson, sabotage, and a broader kidnapping plot against young Gareth.

Emmeline resigns from the Parasol Academy. Though Mrs. Temple scolds her for revealing major magic before a duke, the Academy’s True Love Clause allows the marriage, and Emmeline is gifted a small reserve of Fae thread so she may keep a little magic. By summer 1851, Emmeline and Xavier are wed, the Westminster commission is his, the villains are imprisoned, and the wards have become their children in every way that matters.

On Gareth’s birthday at Kingsgate Beach, Emmeline tells Xavier she is pregnant. The children call them Mama and Papa, and the family steps into a future built from trust, laughter, and perfectly kept time.

Characters

Emmeline

Emmeline is the emotional and moral center of The Nanny’s Handbook to Magic and Managing Difficult Dukes. At twenty-five, newly trained at the Parasol Academy, she begins as a competent but anxious young woman who feels she must be flawless to survive in a world that judges nannies harshly.

Her hidden pressures—widowhood, a ruined household, and a father imprisoned for debt—shape her urgency and her sensitivity toward children who act out from grief. Emmeline’s defining traits are resilience, principled compassion, and a quietly daring intelligence.

She refuses to normalize cruelty, especially corporal punishment, and her belief that children are never “wicked,” only hurting or bored, becomes the philosophy that heals the St Lawrence household. Her Academy education gives her unusual power for someone of her social position: she is magically skilled, methodically trained, and physically capable, which allows her to be both caregiver and protector.

Over the course of the story she changes from a woman clinging to rules for safety into someone who can reinterpret them with confidence and love. Her romance with Xavier does not erase her professionalism; instead, it grows from mutual respect and shared vulnerability.

Even when love becomes central, Emmeline retains agency and boundaries, refusing gratitude-based intimacy and insisting on desire, dignity, and choice. By the end she has forged a new identity not as a servant in someone else’s home but as the co-author of her own family and future.

Xavier Mason

Xavier is introduced as an austere, overburdened aristocrat whose intellect and duty have left him emotionally underfed. A horologist obsessed with creating clocks worthy of Westminster, he measures life in precision and systems, yet his own household operates in grief-driven chaos.

His initial stiffness with Emmeline masks insecurity: he is young for his rank, newly responsible for three orphaned wards, and painfully aware that the people around him suspect instability. The sabotage against him feeds his guardedness, but it also reveals his courage and loyalty, since he prioritizes his wards’ safety over pride or appearances.

Xavier’s humor is dry and surprisingly gentle, and his attraction to Emmeline is rooted in admiration for her competence rather than entitlement. What makes him compelling is the way he learns to trust—first her abilities, then her judgment, then his own heart.

His confession of virginity is not played for helplessness but for honesty; it signals a man who has lived under duty’s shadow, inexperienced yet eager to learn in a way that respects Emmeline’s autonomy. As the story progresses, Xavier becomes less a lonely craftsman hiding behind work and more a partner who actively chooses tenderness, family, and vulnerability.

His proposal and later public defense of Emmeline show that love for him is not a private indulgence but a responsibility he embraces with the same seriousness he brings to clockmaking.

Horatio Ravenscar

Horatio is far more than comic relief; he functions as both messenger and conscience in Xavier’s world. As an urbane, telepathic raven with theatrical diction and a mischievous streak, he bridges the human and magical spheres, highlighting Emmeline’s unique ability to communicate mind-to-mind with animals.

His personality is flamboyant, observant, and loyal to Xavier, but he also has an independent moral compass. Horatio’s fascination with Emmeline begins as curiosity, yet quickly evolves into respect for her courage and her ability to steady a collapsing household.

He frequently provides key information—about nursery upheavals, the sabotaging thugs, and the fire—making him a plot catalyst as well. Symbolically, Horatio represents the wild intelligence of the Fae-adjacent world that Parasol nannies manage with secrecy and care.

His playful pirate squawks, his appetite for drama, and his sharp protectiveness make him a kind of unofficial family member long before Emmeline and Xavier openly become one.

Harriet “Harry” Mason

Harry is the eldest ward and the household’s storm front: brilliant, restless, and armored by grief. At nine, she is old enough to feel the ache of her parents’ absence sharply but too young to process it without mischief and control-seeking.

Her scientific curiosity—frogs, trebuchets, ginger beer experiments, clock experiments—shows a mind that needs challenge, structure, and recognition. Under previous nannies, that energy was treated as defiance; under Emmeline, it is treated as a signal.

Emmeline’s refusal to shame her, especially after the ginger beer disaster, allows Harry to redirect her need for power into collaborative purpose. The “Great Clock Mystery” becomes Harry’s emotional lifeline: a project big enough for her intellect and meaningful enough to make her feel essential to family stability.

Her insistence on being called “Harry” underscores her desire to define herself beyond the expectation placed on grieving girls. Over time, she shifts from testing adults to trusting them, and her leadership turns less destructive and more protective, especially toward her brothers and pets.

Bartholomew Mason

Bartholomew is the middle child and the emotional barometer of the wards. He is lively and mischievous in public moments—fighting over beetles, collecting animals, joining experiments—but beneath that is a soft vulnerability that surfaces in private with Emmeline.

His confession that he misses his parents and wants hugs reveals the profound need for affection that the household has been failing to meet. Unlike Harry, whose grief comes out as control and intellect, Bartholomew’s grief comes out as longing and impulsive play.

Emmeline’s immediate tenderness toward him, and her willingness to engage his childlike joys without ridicule, gives him the security to speak honestly. He helps show the reader that the children’s trouble is never cruelty but mourning.

Through him, the story emphasizes that emotional care is as crucial as discipline, and that a child who feels safe becomes less chaotic because he no longer needs to beg the world to notice him.

Gareth “Gary” Mason

Gary is the youngest and most quietly endangered by the upheaval around him. At six, he is still forming his sense of stability, and his smallness makes him a symbol of what Xavier fears losing and what Emmeline is determined to protect.

His tin soldier and his presence among the sticky chaos of the ginger beer explosion place him in the story as a child who absorbs tension more than he creates it. The kidnapping plot against him is a reminder that innocence can be a target in aristocratic power struggles.

Gary’s gradual integration into Emmeline’s gentle routines and the eventual family scene where he celebrates his birthday surrounded by care show his arc moving from vulnerable orphanhood into secure belonging. He is also part of the story’s final emotional resolution, when the children choose to call Emmeline and Xavier Mama and Papa, indicating that even the youngest has learned to trust home again.

Mina Davenport

Mina is Emmeline’s early anchor at the Academy, offering comfort without condescension. In the opening, her role is to show Emmeline as someone loved and understood even before she enters the St Lawrence world.

Mina’s sensitivity to Emmeline’s nerves and her quiet companionship suggest that Parasol nannies form sisterhoods as survival networks. Though she does not dominate the later plot, Mina is important as a mirror of what Emmeline might have been if life had stayed within the Academy’s safe walls.

Her presence also reinforces that Emmeline’s courage is not solitary; it is built from friendships and community that teach women to stand upright in rigid society.

Mrs. Temple

Mrs. Temple embodies benevolent authority: strict where professionalism and secrecy are concerned, but humane where a student’s soul is at risk.

Her decision to reassure Emmeline after the luncheon mishap signals that she sees beyond etiquette to the person underneath. She is also a living bridge between institutional rules and compassionate flexibility, which becomes crucial at the end when she interprets the True Love Clause and grants Emmeline continued access to modest magic.

Mrs. Temple’s steady guidance shows that the Academy is not merely a magical finishing school but a protective system for women navigating class, labor, and danger.

She respects Emmeline’s strength, but she also expects accountability, making her a balanced mentor rather than a convenient ally.

Nanny Snodgrass

Snodgrass represents the old regime of child-rearing: punitive, contemptuous, and more concerned with obedience than healing. Her language toward Harriet—calling her wicked and demanding birch punishment—reveals a worldview where children’s grief is treated as moral failure.

Snodgrass’s quick dismissal by Xavier after the flour-bomb incident shows that the household is ready for change even before Emmeline is fully installed, but Snodgrass’s presence matters because she defines what Emmeline must oppose. She is less a nuanced character than a structural contrast, illustrating how cruelty disguised as discipline damages children and destabilizes homes.

Woodley

Woodley is the stern butler who embodies the household’s formal spine. His recognition of Emmeline from the roof incident and his measured acceptance of her into the house suggest loyalty to Xavier mixed with a cautious assessment of newcomers.

Woodley’s function is subtle but important: he indicates that St Lawrence House has rules and an established rhythm that Emmeline must learn to conduct, not overthrow. His sternness is not villainy but guarded professionalism, and his willingness to admit her implies he trusts Xavier’s judgment even if the choice is unconventional.

Frederick “Freddy” Evans

Freddy is Emmeline’s brother and a living source of her conflicted duty. He is desperate, unreliable, and reckless enough to drag the family into ruin, yet also human enough to regret and apologize.

His clutching of Emmeline outside St Paul’s shows how his panic turns to coercion, collapsing sibling bonds into transactional need. At the same time, his shaken response to Xavier’s rapier and his vow to fix the Oberon suggest that he is not malicious, just immature and drowning.

Freddy’s character is a reminder that Emmeline’s heroism does not emerge from isolated romance alone; it also involves surviving painful family entanglements and learning how to love without being consumed by someone else’s failures.

Edward Evans

Edward is Emmeline’s father, defined by sacrifice and quiet dignity. His imprisonment for debt is a shadow over Emmeline’s entire early arc, making him the emotional reason she risks everything for stable employment.

His former life as a clock-shop owner links Emmeline to horology and creates a meaningful partnership with Xavier, who recognizes his skill. Edward’s release and hiring are not just plot kindnesses; they restore Emmeline’s sense of family worth and allow her to stop living in constant guilt.

Edward functions as a stabilizing elder presence, validating Emmeline’s competence and giving her a personal home base within the duke’s estate. His story also underscores the cruelty of debt culture and the vulnerability of good men in a rigid economy.

Sir Randolph Redvers

Randolph is the social and professional antagonist to Xavier: arrogant, entitled, and theatrically contemptuous. His public rudeness in the museum and his flirtation with Emmeline are calculated humiliations meant to assert dominance.

What makes Randolph dangerous is that he weaponizes charm and status to disguise sabotage. His eventual role in arson and attempted murder reveals that beneath his polished rivalry is moral rot and desperation.

Randolph is not simply jealous; he is willing to destroy lives for prestige, embodying the worst of aristocratic competition. He also provides the story’s clearest contrast to Xavier’s integrity, proving that ambition without empathy becomes brutality.

Algernon Mason

Algernon is a more intimate villain because his betrayal rises from family blood. As Xavier’s cousin, his resentment isn’t about a single contest but about a perceived entitlement to the dukedom.

His participation in bribery, rumor-spreading, and the fire shows how envy can hollow out kinship into predation. Algernon’s partnership with Randolph is opportunistic but poisonous, illustrating that personal grievance and external rivalry can fuse into a lethal alliance.

If Randolph represents corrupted ambition, Algernon represents corrupted inheritance: a man who believes power should fall to him by right and is willing to burn his own family to seize it.

Constable Thurstwhistle

Thurstwhistle begins as a figure of mundane authority, appearing during the chaotic arrest misunderstanding when Emmeline leyports into Belgrave Square. Later, he represents lawful restoration once the villains are exposed.

He is not deeply personalized, but his actions matter: he is a reminder that even in a magical world, public institutions exist, and justice can respond when truth becomes visible. His presence at the end, arresting Randolph and Algernon, helps shift the story from private rescue to public consequence.

Mrs. Lambton

Mrs. Lambton serves as the household’s internal administrator and quietly maternal presence among the servants.

Her choice to summon Emmeline to meet her freed father shows that she is aligned with Xavier’s benevolence and invested in Emmeline’s happiness. She is also a marker of the house’s transformation: when Emmeline arrives, servants are fleeing in fear and rumor; through Mrs.

Lambton’s continued steadiness, we see a staff slowly regaining confidence in their home. She is a secondary character, but she participates in the emotional architecture of the restored household.

Queen Maeve

Queen Maeve is a distant yet decisive force as the Fae authority who validates the Academy’s rules and the boundaries of permissible magic. Her consultation at the end frames the magical system as governed, not whimsical, and gives Mrs.

Temple a legitimate basis for allowing Emmeline to keep a thread of power. Queen Maeve stands for the moral order of the magical world: she does not erase consequences, but she recognizes love and intention.

Even without much direct presence, her influence shapes the ethical tone of how magic should be used.

Archimedes and Aristotle

Archimedes the frog and Aristotle the terrapin may be animals, but in The Nanny’s Handbook to Magic and Managing Difficult Dukes they are emotional signposts. Archimedes reflects Harry’s scientific curiosity and need for control; her calm explanation of his species under stress shows her intellect struggling to be heard.

Aristotle and the jar of crickets that pop from Emmeline’s pockets act as wonder-stirrers for Bartholomew, demonstrating Emmeline’s almost magical ability to meet children where they are. These pets symbolize a household shifting from rule-based fear to affectionate discovery, and they help build the children’s bonds with Emmeline through delight rather than discipline.

Themes

Professional identity, competence, and the cost of care

Emmeline’s journey in The Nanny’s Handbook to Magic and Managing Difficult Dukes centers on what it means to be truly competent in a role that society treats as both invisible and indispensable. From the opening embarrassment at the Academy luncheon, her competence is not portrayed as effortless polish but as something forged under pressure.

She is not merely learning etiquette; she is trying to survive a world where a single lapse can mean unemployment, and unemployment means her father remains in prison. That desperation adds weight to her professionalism.

Care work here is skilled labor with emotional and physical stakes, not a warm hobby. The Parasol Academy’s training in self-defense, magical restraint, and discretion positions nannies as guardians who must be calm in chaos and morally firm when power presses down.

Emmeline’s refusal to accept corporal punishment is not just personal preference; it is a declaration that her authority is rooted in ethics rather than fear. Her steady handling of Harriet’s experiments, the boys’ fights, and the museum incident shows a kind of competence that includes improvisation, psychology, and risk management.

At the same time, the story highlights the hidden cost of such competence. Emmeline must constantly police her own emotions and desires to remain employable and “proper.

” She comforts grieving children while suppressing her own grief and financial panic. Even after she becomes essential to the duke’s household, her position remains precarious because it rests on reputation.

The expectation that she be endlessly patient, self-sacrificing, and grateful exposes how care workers are often asked to carry burdens that wealthy families would rather not acknowledge. Yet the book also refuses to reduce her to martyrdom.

Her skills earn respect that changes the household’s power balance, and her professionalism becomes a path to agency. She does not gain worth because a duke loves her; the duke recognizes her worth because her labor, discipline, and judgment repeatedly save his family.

Power, secrecy, and the ethics of magic

Magic in The Nanny’s Handbook to Magic and Managing Difficult Dukes is not a simple ornament; it is an instrument of power shaped by strict rules and social fear. Leyporting, spells hidden in umbrellas, and emergency dust granted by the Fae all exist inside a system that demands concealment from the public.

That demand builds a constant moral tension: magic can solve problems swiftly, but using it openly risks social collapse, persecution, or political backlash. Emmeline is trained to treat magic like a regulated profession.

The Academy’s rules about using certain spells only in “true calamities” mirror modern ideas of restricted force. When she uses decalamitifying dust after the ginger-beer disaster or the fire, the act is framed as both lifesaving and dangerous because it crosses a boundary into powers not meant for casual use.

Her restraint makes her trustworthy; her willingness to break rules in emergencies makes her heroic.

Secrecy also creates inequality. The upper-class world benefits from magical solutions without bearing the risk of exposure, while workers like Emmeline absorb the danger of being accused, dismissed, or criminalized.

The constable scene shows how an ordinary authority figure reacts to magic with suspicion, while the Academy has arranged for elite discretion. This implies a social order where magic is tolerated only when controlled by institutions aligned with power.

The Fae themselves add another ethical layer. Their gifts arrive through prayer and need, suggesting a moral economy where magic responds to mercy, courage, and love rather than entitlement.

Yet that mercy is unpredictable. Emmeline cannot command the dust; she can only ask.

This keeps her humble and prevents magic from becoming a tool of domination.

Finally, magic is tied to truth and emotional integrity. The appearance of the True Love Clause in the handbook is a quiet argument that systems can be rigid yet still contain room for human reality.

Emmeline’s story shows that ethical magic is less about purity and more about responsibility: when to act, whom to protect, and what costs to accept. The book treats power as acceptable only when linked to care, restraint, and accountability, and it critiques any use of power for vanity or sabotage through the villains’ contrast.

Grief, misbehavior, and the making of a family

The children of St Lawrence House are not presented as “difficult” in a vacuum; their chaos is a language of grief. The death of their parents sits behind nearly every act of rebellion, from frogs in nurseries to flour-bomb trebuchets and exploding ginger beer.

Harriet’s cool expertise and constant experiments are ways of holding control in a world that has already proven unstable. The boys’ clinging need for park trips, pets, and hugs shows grief expressed through longing rather than anger.

Emmeline’s success comes from recognizing this emotional root. She does not treat misbehavior as sin but as a signal.

Her conversation with Harriet after the ginger-beer disaster uses vulnerability instead of authority: she admits her own rooftop foolishness and reframes rules as protection rather than punishment. That exchange is crucial because it shifts Harriet from adversary to collaborator.

The household gradually becomes a chosen family shaped by mutual repair. Emmeline does not replace the children’s parents as a blank substitute; she helps them live with absence while building new bonds.

Bartholomew’s confession that he misses his parents and wants hugs is handled without sentimentality. It is direct, painful, and met with direct care.

Xavier also grows through this process. His initial stiffness is partly grief and partly isolation.

He is trying to build a monumental clock while his home unravels, so the children’s disorder reads to him as threat. Emmeline offers a model of authority that includes tenderness, and Xavier learns to trust that model.

The romance does not pull Emmeline away from the children; it pulls the household together. When the children ask to call them Mama and Papa at the end, it lands as earned rather than automatic because we have seen the long process of safety returning to the house.

Even Horatio the raven and the assortment of pets play into this theme, turning the home into a lively ecosystem rather than a cold aristocratic monument. The story suggests that family is not defined by blood alone but by steady presence, shared risk, and the willingness to stay when staying is hard.

Love, consent, and crossing social boundaries

The romance in The Nanny’s Handbook to Magic and Managing Difficult Dukes is shaped by a firm emphasis on consent and emotional clarity, especially given the class gap and employment relationship. The first kiss happens in a moment of danger, but the aftermath is not swept away as a romantic inevitability.

Both characters explicitly state boundaries and the need to stop, showing an awareness that desire alone does not make an action right. Later intimacy is negotiated again, with Emmeline insisting that gratitude for her father’s freedom is not a license for Xavier to claim her.

His response is equally important: he names his own inexperience, refuses coercion, and asks for mutual choice. The scenes highlight pleasure as something learned together rather than taken.

In a genre context where aristocratic power could easily tilt toward entitlement, this insistence on consent becomes a moral anchor.

Crossing boundaries is also social. A duke proposing to his nanny challenges hierarchies built on distance.

The book does not pretend those hierarchies vanish; they create real friction through Academy rules, gossip risk, and Emmeline’s fear of being seen as opportunistic. Her professionalism makes the romance more complicated, not less.

She resists the idea that personal feelings should dismantle her identity or ethics. When she burns her nanny cap, it is not a rejection of care work but a conscious decision to step into a new social role on her own terms.

Xavier’s love is framed as recognition of Emmeline’s strength rather than rescue fantasy. He helps her father, yes, but he also repeatedly depends on her judgment, bravery, and magic.

The resolution through the True Love Clause suggests that institutions can adapt when confronted by genuine human bonds, but it also implies that women’s paths to legitimacy are still policed by rules. The romance becomes a way of arguing for partnership across class when it is rooted in respect, transparency, and shared responsibility.

Love here is not a reward; it is a choice made despite risk, and sustained through daily actions that prove trust.

Time, order, and resisting sabotage

Clocks and timekeeping are more than Xavier’s career; they are the story’s symbolic structure for control versus instability. The Great Clock Mystery at St Lawrence House turns domestic life into a battleground where time itself misbehaves.

The speeding and slowing clocks mirror the household’s emotional disruption after loss and the deliberate interference of enemies. In that sense, time becomes a measure of trust.

When clocks cannot be relied on, routines collapse, tempers flare, and fear grows. The sabotage is not merely a plot device; it demonstrates how fragile order can be when people act in bad faith.

Emmeline’s fascination with horology offers a counterpoint to chaos. She introduces a project that gives Harriet constructive mastery over uncertainty.

Resetting clocks repeatedly is tedious work, but it also teaches patience and accountability. The eventual discovery of the synchronization spell, newly appearing in the handbook, suggests that order is not fixed; it can be learned, earned, and sometimes revealed only when someone is ready to use it responsibly.

Her spell aligns the household’s clocks to Greenwich time, which is a powerful metaphor for shared reference. The household begins to run on a common rhythm again, not because problems vanish, but because people are working together toward alignment.

Xavier’s “Queen of Clocks” and “King of Clocks” designs extend this theme from the home to the nation. A public clock at Westminster symbolizes collective coordination and civic identity.

The villains’ attempt to steal the plans and burn the house shows the opposite impulse: breaking time, breaking trust, and claiming status through destruction. Their defeat restores not just property but moral order.

The fire that vanishes under decalamitifying dust is a moment of restoration that refuses to let sabotage define the future.

By the end, time shifts from enemy to promise. The household is no longer trapped by the past or by disrupted rhythms.

Pregnancy and children calling them Mama and Papa place the story’s final emphasis on future continuity. Timekeeping, then, becomes a way of talking about healing: not forgetting what was lost, but building a stable present where the future feels possible again.