The Naturalist Society Summary, Characters and Themes

The Naturalist Society by Carrie Vaughn is a luminous blend of historical fiction and subtle fantasy set in an alternate 19th century where science and magic intersect through the discipline of Arcane Taxonomy. The story explores the interior lives of naturalists, particularly those sidelined by the constraints of gender, race, and societal expectation.

At its heart is Elizabeth “Beth” Stanley, a brilliant but uncredited scientist who, alongside explorers Anton Torrance and Bran West, navigates grief, ambition, romance, and reinvention in a world shaped by curiosity and power. This novel is both a meditation on visibility and erasure and a tribute to the pursuit of wonder in the natural world.

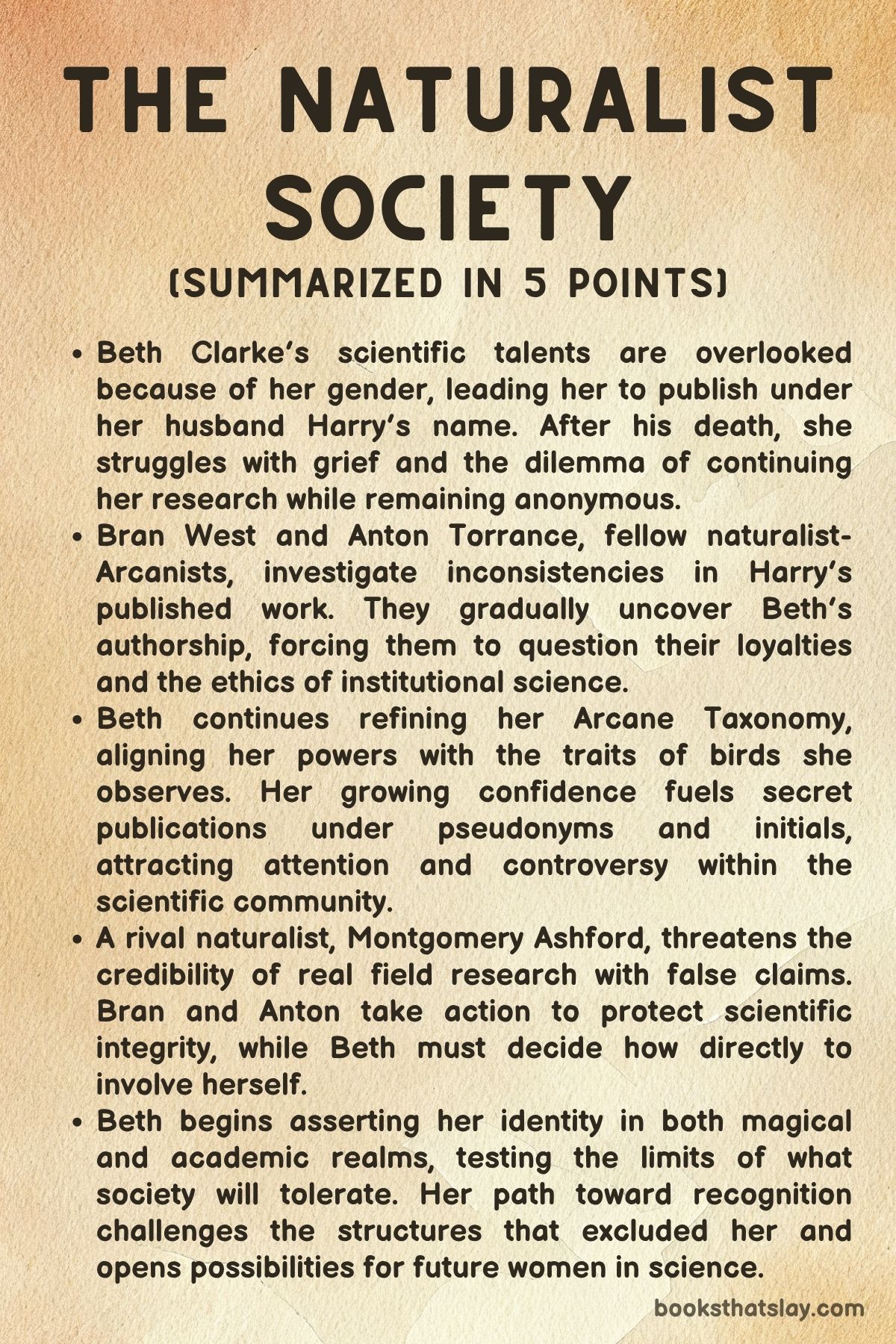

Summary

In the opening section of The Naturalist Society, Elizabeth “Beth” Clarke establishes her voice through ornithological field journals addressed to her friend and suitor Harold “Harry” Stanley. As a woman with keen scientific insight and a gift for Arcane Taxonomy—the mystical classification of flora and fauna—Beth is forced to work under social limitations.

Harry, who admires and encourages her work, proposes that she publish her findings under his name to bypass gendered institutional barriers. He supports her both emotionally and professionally, culminating in a marriage proposal.

Their partnership is sealed not only by affection but by a quiet act of Arcane power: Beth draws warmth from the memory of a mandarin duck to heat their tea, showing how intimately her emotional and scientific worlds are linked.

The story transitions to the Arctic, where Harry’s close friend, Bran West, conducts research alongside Anton Torrance. They survive harsh conditions and a near-deadly polar bear encounter by drawing on Arcane abilities.

Their mutual reliance fosters a romantic connection in the isolation of their expedition hut. In this environment of snow and science, Bran and Anton find love, companionship, and equal footing.

As they plan further adventures, their relationship becomes both a personal and professional alliance, marked by warmth in a freezing landscape.

Years pass, and Beth tends to a dying Harry, powerless to cure his disease. Despite her deep knowledge and magical gifts, she is unable to name or neutralize the bacteria afflicting him.

Her anguish is compounded by the institutional refusal to recognize her efforts, even as their home is filled with scientific observations and shared memories. Harry’s death leaves Beth suspended between mourning and frustration, aware that she cannot lay claim to the work they built together under his name.

Bran and Anton, returning from the Arctic, visit Beth to collect Harry’s scientific notes. In Harry’s study, they notice irregularities—the handwriting, terminology, and recent data reflect Beth’s style.

She calmly reveals that she was the true author behind much of Harry’s publicized research. Bran, stunned, acknowledges her genius and the quiet deception that allowed her talents to be hidden in plain sight.

The two men leave, carrying a newfound respect for Beth and a promise to preserve her secret.

Beth withdraws into the solitude of her garden, filled with birds and the vestiges of her studies. Her sanctuary becomes a metaphor for her autonomy.

Though denied formal recognition, she claims her identity with certainty. Watching a chickadee, she finds a small peace in solitude, fully inhabiting the life and mind that had once been suppressed.

The story picks up with Anton and Bran navigating the politics of the prestigious Naturalist Society. As they campaign for an Antarctic expedition, they must contend with both admiration and skepticism.

Anton, with his noble lineage and composed demeanor, must balance public expectations with private truths. Bran’s Arcane expertise draws attention, but also underscores his social awkwardness.

Their past with Harry follows them, especially as his legacy is debated and contested.

Beth’s presence lingers in subtle ways. Though rejected when she attempted to publish under Harry’s name, she maintains her research privately.

Meanwhile, a rival, Montgomery Ashford, emerges, claiming dramatic discoveries and threatening Anton and Bran’s credibility. Ashford’s bravado contrasts with their meticulous approach, creating friction and challenging the integrity of their mission.

During this time, Anton encounters Beth in Central Park, where her solitary bird-watching reflects her commitment to nature and continued work. He invites her to attend a lecture, hoping to draw her into their world again.

At the lecture, Beth appears in mourning attire, observing from the margins. She watches Anton and Bran bring their Arctic stories to life and sees the spectacle that science must sometimes become to win support.

At the reception, she quietly dismantles Ashford’s arrogance and garners support for Anton and Bran, earning respect. She later shares her work with them over tea, including unpublished essays and journals.

They encourage her to find a wider audience, and she begins to reassert her identity as a scientist on her own terms.

Beth’s attempt to publish in a women’s magazine represents a shift in strategy—one away from institutional validation and toward community engagement. Her piece encourages women to observe birds rather than wear them as fashion, turning observation into activism.

A confrontation with Ashford at the Society underlines her precarious social standing and the desire of powerful men to co-opt her talents. After enduring both insult and exclusion, Beth retreats again, recognizing the danger in being visible but also the strength in her isolation.

Beth begins to form an Arcane bond with a finch, one so deep she can see through its eyes. This private breakthrough is not shared publicly; it’s a moment of quiet triumph and deeply personal empowerment.

As Bran and Beth grow closer, their shared love of science leads to romance, but tension arises when he questions her choice to publish emotionally resonant work. She reveals that her marriage to Harry was likely platonic, a revelation that reframes her emotional past and deepens her bond with Bran.

Despite their growing intimacy, Bran’s inability to fully grasp her need for control over her narrative becomes a strain.

Anton, sensing Bran’s attachment to Beth, pulls away. The romantic triangle among Beth, Bran, and Anton underscores the emotional complexity of their relationships and the conflicts between personal desire, loyalty, and intellectual partnership.

Bran struggles with his feelings for both Anton and Beth, neither of whom can offer him a simple resolution.

Later, Bran falls gravely ill, and Beth is committed to an asylum by relatives who disapprove of her independence. Using careful observation and strategic planning, she escapes and reinvents herself in Colorado as Stanley Clarke.

There, she teaches, writes, and finds freedom. Her pregnancy complicates matters, but rather than hindering her, it becomes a new source of strength.

Anton and Bran eventually track her down through a birding article and reunite with her. Their reunion is bittersweet, marked by transformation, affection, and the acknowledgement that Beth has carved out a life entirely her own.

As Anton and Bran prepare for the Antarctic expedition, Ashford again threatens their chances. A dramatic presentation of Arcane skill by Bran impresses the selection committee and wins the expedition for them.

But Bran’s health excludes him from participating. He stays behind with Beth, caring for her and their daughter while Anton sails south.

The final moments are tender and hopeful. Letters, shared dreams, and migratory birds tie them together.

Two years later, Anton returns from Antarctica changed but alive. At the dock, Beth, Bran, and their daughter Ava welcome him back, forming a family chosen by love, resilience, and mutual respect.

Their reunion affirms that while formal recognition may elude them, the legacy of their work—and their connection—endures beyond societal constraints.

Characters

Elizabeth “Beth” Clarke / Beth Stanley / Stanley Clarke

Beth is the emotional and intellectual center of The Naturalist Society, evolving across the story from a brilliant but silenced naturalist to a woman who fully claims her power, voice, and agency. Initially introduced as a young, passionate ornithologist whose talents are stifled by the rigid expectations of 19th-century society, Beth finds a tentative partner in Harry Stanley, who recognizes her abilities but still suggests she publish under his name.

Their bond is affectionate and marked by shared intellectual pursuits, but it becomes clear over time that Beth bore the true weight of their work, her contributions hidden beneath his name. Her grief after Harry’s death is not just personal—it is existential, shaking the foundation of her life’s mission and challenging her faith in Arcane Taxonomy to heal or protect.

As the narrative progresses, Beth’s isolation deepens, especially when Harry’s peers attempt to co-opt his legacy, only to realize that Beth was the true scientific force all along. Her revelation to Brandon and Anton—claiming her authorship and magical expertise—is a pivotal moment of defiance and self-assertion.

Her later interactions at the Naturalist Society expose the entrenched misogyny she faces, particularly in conversations with the likes of Montgomery Ashford, whose manipulative charm and disregard for genuine science pose both a professional and personal threat. Beth’s subtle, strategic resistance—using her knowledge to gently dismantle Ashford’s arrogance and then choosing to publish her essay in a women’s magazine—is a radical shift in her alignment.

No longer seeking validation from patriarchal institutions, she redirects her message to an audience that will listen and learn: other women.

Her time in the asylum and subsequent escape mark a critical transformation. Stripped of freedom but not her intellect, Beth uses her powers of observation and resilience to reclaim her autonomy.

Reinventing herself as Stanley Clarke, she flourishes in anonymity, publishing, teaching, and eventually embracing motherhood on her own terms. Her relationship with Bran becomes a complex mix of romantic connection, scientific kinship, and mutual healing, though she remains wary of being idealized.

In the end, Beth is a figure of immense quiet strength, whose arc charts a steady migration from erasure to embodied power—finding freedom in birdsong, solitude, and a self-crafted identity unmarred by the constraints of her time.

Harold “Harry” Stanley

Harry Stanley is a gentle, well-meaning, and progressive man, but ultimately a symbol of the compromises that intelligent women like Beth were forced to make in a society hostile to female intellect. He genuinely admires Beth and supports her scientific endeavors, proposing marriage as a partnership of minds as well as hearts.

However, his willingness to let Beth publish under his name—though intended as a pragmatic solution—nonetheless exemplifies the systemic erasure of women. He is more vessel than visionary, a man who benefits from his wife’s genius while she remains unseen.

Even after his death, Harry’s shadow looms large. His study and published work become contested spaces, drawing men like Brandon and Anton into the realization that Harry’s acclaim was built on borrowed brilliance.

Beth mourns him deeply, but it becomes evident that their marriage was more platonic than passionate, possibly shaped by Harry’s own unspoken sexual identity. Their partnership, while affectionate and respectful, was constrained by societal expectations and personal silences.

Ultimately, Harry is both a source of comfort and an unintentional obstacle—a loving man who could not, or would not, fight harder to make Beth visible. His legacy becomes one Beth must gently dismantle to forge her own.

Brandon “Bran” West

Brandon West is a celebrated Arcanist and explorer, defined by a piercing intelligence, deep emotional restraint, and complex desires that evolve throughout The Naturalist Society. A figure of precision and control, he initially appears as a master of Arcane Taxonomy in extreme environments—using his skills to suspend time, hunt seals, and survive in the Arctic.

His romantic relationship with Anton Torrance adds emotional depth to his otherwise reserved persona, revealing a quieter, tender side grounded in loyalty and trust. However, Bran is not immune to ego or blindness; when confronted with the truth of Beth’s authorship, he is stunned, his worldview subtly cracked.

As the story unfolds, Bran’s feelings for Beth begin to emerge, complicating his bond with Anton and reflecting his shifting internal compass. His attraction to Beth is intellectual as much as romantic—her strength, knowledge, and mystical insight resonate with his own need for connection beyond the academic.

Yet his disappointment in her choice to publish a personal, emotional essay in a women’s magazine reveals a streak of condescension. Beth’s response forces him to reassess the gendered lens through which he judges scientific worth, leading to growth and deeper humility.

Bran’s vulnerability peaks during his illness and subsequent exclusion from the Antarctic expedition, which he had long pursued. His quiet acceptance of this reality—and his decision to remain with Beth and Ava—cements his transformation.

Once a man defined by arcane mastery and distant rigor, he ends the narrative grounded in emotional intimacy and family. His longing, grief, and intellectual hunger are transmuted into something gentler and more enduring: love, not conquest, becomes his final ambition.

Anton Torrance

Anton Torrance is a man of contrasts—noble yet modest, hardened by expeditions yet deeply affectionate, especially toward Bran. As a mixed-race son of a British nobleman, Anton carries the burden of navigating class and racial prejudice with stoic composure.

He is constantly performing respectability to maintain his standing in elite scientific circles, aware that one misstep could cost him everything. His bond with Bran is longstanding and tender, but he also harbors a quiet jealousy, especially when Bran’s affections appear to drift toward Beth.

Anton’s charm and storytelling prowess make him a compelling public figure, essential in securing support for expeditions. However, his public persona masks a deep sense of vulnerability and a need for affirmation—not just from society, but from those he loves.

His reactions to Bran’s interactions with Beth are marked by subdued heartbreak rather than confrontation, illustrating his emotional maturity but also his deep hurt. Despite this, Anton remains committed to their shared goals and endures immense personal sacrifice—eventually embarking on the Antarctic expedition alone when Bran is deemed unfit.

His return, thin and transformed by the ice, is triumphant yet emotionally raw. The reunion with Beth, Bran, and their daughter Ava is not only a moment of personal victory but the fulfillment of a chosen family narrative.

Anton, who once seemed like a man burdened by legacy and duty, ends the tale as someone who has carved out belonging—not through lineage or status, but through loyalty, endurance, and love.

Montgomery Ashford

Montgomery Ashford is the antagonist of The Naturalist Society—not in the traditional villainous sense, but as a foil to the central trio’s ethos of rigorous, respectful science. Charismatic, performative, and opportunistic, Ashford represents a strain of scientific exploration driven by spectacle and self-aggrandizement.

His dubious claims—like rediscovering extinct species—are designed more for headlines and patronage than truth. In contrast to Anton’s quiet credibility and Bran’s precision, Ashford thrives on manipulation, racial microaggressions, and dismissiveness toward women.

His encounter with Beth at the Naturalist Society is especially telling. He sees her not as a peer but as an asset to be exploited, weaving innuendo and flattery into their conversation in an attempt to extract information.

He embodies the worst aspects of the scientific establishment: entitlement, misogyny, and a hunger for power under the guise of progress. Beth’s eventual public dismantling of his arrogance, without resorting to confrontation, serves as one of the most satisfying narrative reversals.

Ashford’s failure to secure the Antarctic expedition grant—despite all his flair—underscores the story’s commitment to substance over showmanship, and his role as a cautionary figure in the politics of scientific recognition.

Ava

Though Ava, Beth’s daughter, appears only briefly in the narrative, her symbolic importance is profound. She is the embodiment of new beginnings—born from a woman who has fought to reclaim her name, knowledge, and freedom.

Ava represents continuity between generations of women who observe, nurture, and protect, as well as a life unburdened by the false binaries of science and magic, male and female authority. In the final scene, when Beth, Bran, and Anton reunite to greet Ava’s father, Anton, on the pier, she becomes a living testament to love’s endurance and the resilience of chosen family.

Her presence ensures that Beth’s legacy is no longer hidden or denied, but joyfully, and defiantly, alive.

Themes

Gendered Erasure and Scientific Identity

Throughout The Naturalist Society, Beth Clarke Stanley’s journey is shaped by the persistent erasure of her scientific accomplishments due to her gender. The very foundation of her public identity is a compromise: publishing under her husband’s name because women are barred from recognition in formal scientific circles.

This compromise, while seemingly protective and strategic, slowly fractures her sense of self and stifles her legitimacy. Even her magical talents, honed through Arcane Taxonomy, are constrained by the same societal prejudices—permitted only in private or masked through male intermediaries.

As the narrative expands into the political space of the Naturalist Society, the layers of institutional bias become more complex. Beth is not just excluded from professional acknowledgment; her work is appropriated, misunderstood, or dismissed entirely.

The moments where she asserts her authorship and expertise are fraught with risk and revelation. Her use of bird journals, her essay in a women’s magazine, and her final decision to adopt a male pseudonym highlight both her resilience and the painful necessity of self-effacement.

Her eventual triumph is quiet—rooted in independence rather than institutional validation. By reclaiming authorship and reshaping her path as Stanley Clarke, she constructs an identity that cannot be owned or overwritten by others.

This theme encapsulates the constant tension between knowledge and power, and the cost of invisibility for women in male-dominated intellectual spheres.

Love, Partnership, and Unconventional Families

The emotional architecture of The Naturalist Society is anchored by relationships that defy traditional definitions. Beth and Harry’s marriage is rooted in deep mutual respect and intellectual companionship, but lacks romantic intimacy, suggesting that their union was a shield against societal constraints more than a fulfillment of romantic or physical expectations.

Harry’s possible same-sex preferences, only hinted at and never judged, underscore how even love in this world must often disguise itself to survive. Similarly, the bond between Bran and Anton exists in the margins—tender, genuine, and complicated by societal pressures that demand discretion.

Their affection becomes a sanctuary against the brutality of exploration and scientific performance. When Beth and Bran find themselves drawn to each other, the connection is as much about shared understanding as it is about emotional vulnerability.

Their romance is not a betrayal but a reconfiguration of needs, shaped by grief, longing, and the desire to be seen without judgment. The eventual formation of a chosen family—Beth, Bran, Anton, and Ava—reflects a radical reimagining of kinship.

It is built not on conformity but on compassion, shared purpose, and mutual survival. The story treats this family structure not as a consolation prize but as a victory over isolation and alienation.

In the end, their ability to love beyond prescribed norms becomes a quiet revolution against a world that tries to define their worth by gender, class, or public acclaim.

Power, Exploitation, and the Ethics of Discovery

The pursuit of scientific discovery in The Naturalist Society is never pure. The magical system of Arcane Taxonomy itself is a metaphor for power—rooted in observation and classification, but also in the ability to control, possess, and manipulate the natural world.

While characters like Beth and Bran use their talents to understand and protect, others like Montgomery Ashford embody a more exploitative ethos. Ashford’s spectacle-driven approach to exploration, his claims of rediscovered species, and his manipulation of public fascination all highlight how science can be perverted into entertainment and conquest.

His interactions with Beth are particularly chilling—he recognizes her intellect but only to the extent that it can serve his ambitions. The institutional structures that enable figures like Ashford are just as culpable.

The Naturalist Society, with its blend of politics, prestige, and patriarchy, reinforces a system where knowledge is commodified and gatekept. Anton and Bran’s struggle to gain funding without compromising integrity mirrors Beth’s own battle for legitimacy.

The contrast between Arcane Taxonomy’s potential for connection and its susceptibility to misuse underscores a larger ethical question: who has the right to knowledge, and at what cost? In this world, discovery is not neutral.

It is shaped by who controls the narrative, who gets credit, and who is allowed to speak.

Grief, Memory, and the Persistence of the Self

Beth’s arc is also a profound meditation on grief—not just for Harry’s death, but for the years of self-denial, the erasure of her authorship, and the silencing of her voice. Her mourning is layered with the weight of all that she could not express while he lived, particularly the ways she subordinated her own brilliance to ensure his public success.

As she tends to Harry in his final days, she is surrounded by the physical artifacts of their shared life, yet she feels disconnected—both grounded and untethered. After his death, the garden becomes her emotional anchor, a space of renewal and solitude where memory lives not in words or accolades, but in birdsong and wind.

The connection she forms with a finch—experiencing the world through its eyes—symbolizes a spiritual integration of memory, loss, and transformation. Rather than seeking external validation for her grief or her past, Beth internalizes these experiences as sources of strength.

Her ability to reinvent herself, to survive institutionalization, and to raise a child on her own terms becomes a testament to her resilience. The memory of Harry does not vanish; it evolves, becoming part of her, not as limitation but as layered history.

In a world that forgets too easily, Beth becomes the keeper of her own memory, her own voice, and her own future.

Observation, Nature, and the Magic of Attention

At the heart of The Naturalist Society is a reverence for observation—not as passive watching, but as an act of intimacy and transformation. Beth’s ornithological work is not just academic; it is devotional.

Her journals, her essays, her ability to draw magic from birds reflect a profound attentiveness to the natural world that borders on sacred. This attention is not goal-oriented; it is relational.

Birds are not specimens to be collected or classified for fame, but beings whose lives, patterns, and migratory rhythms offer emotional and philosophical insight. Bran, too, displays this attentive sensibility, though his failures—such as the misclassification of a hybrid warbler—reveal that observation alone is not enough without humility.

Anton’s physical presence and narrative control contrast with Beth’s quiet seeing, showing how charisma can overshadow deeper forms of knowing. But it is Beth who ultimately transforms attention into power.

Her garden, her essays, her magical connection to birds are acts of reclaiming narrative authority through precision, patience, and care. Even when she chooses not to share her most intimate Arcane experiences, it is not out of fear but out of respect for the sanctity of what she sees.

In a world saturated with performance and spectacle, Beth’s way of seeing becomes a radical act—resisting commodification and insisting on wonder for its own sake. Her story becomes a reminder that the smallest, most consistent acts of observation can be the most enduring forms of knowledge and truth.