The New Jim Crow Summary and Analysis

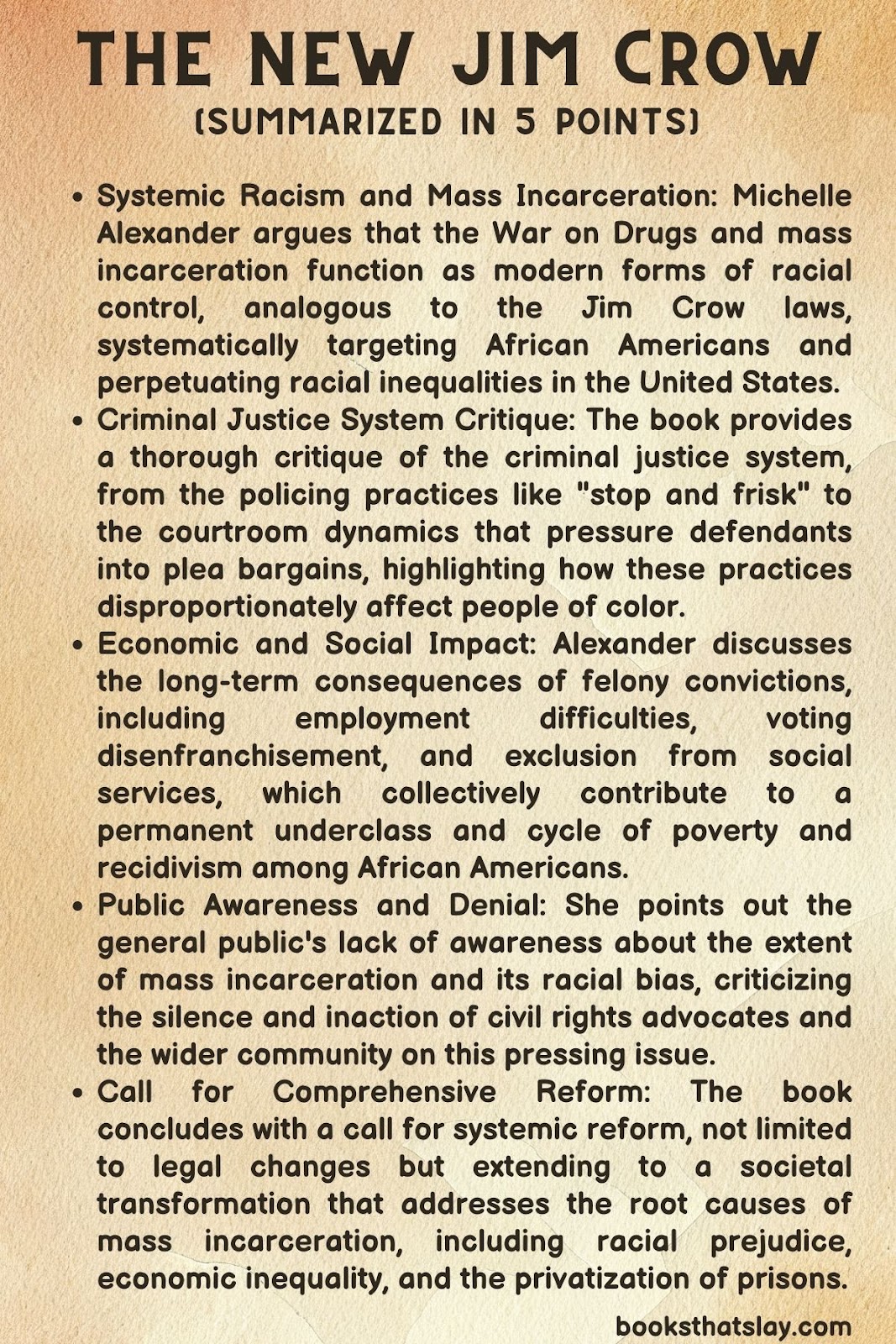

The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander is a landmark work of social critique that argues the United States rebuilt a racial caste system after the formal end of segregation—this time through the criminal legal system. Writing as a civil rights lawyer who once underestimated the issue, Alexander explains how the War on Drugs and “tough on crime” politics created a pipeline that marks millions—especially Black men—as criminals and then shuts them out of jobs, housing, education, public benefits, and voting.

Her core claim is direct: mass incarceration is not a side effect of inequality; it is a modern method of racial control disguised as race-neutral policy.

Summary

Michelle Alexander opens by speaking to people who care about racial justice yet don’t grasp how deep the damage of mass incarceration runs. She introduces the story of Jarvious Cotton, a Black man barred from voting because of a felony conviction.

Cotton’s family history traces a chain of political exclusion across generations: ancestors denied the vote under slavery, later blocked by Jim Crow rules, and now replaced by laws that strip voting rights from people labeled felons. Alexander argues that although explicit racial discrimination has been outlawed, the criminal label has become a legal tool that allows discrimination to continue openly in many parts of American life.

Once someone is classified as a criminal, society can deny them opportunities and basic rights while claiming to be fair because the discrimination is tied to “crime,” not race.

Alexander explains that she did not always see mass incarceration as a racial caste system. Early in her career, she believed rising imprisonment was mainly a consequence of poverty, weak schools, and limited economic opportunity.

Her view shifted when she encountered evidence that the War on Drugs was not simply a crime-control response but a political project that helped restructure racial hierarchy. Working in civil rights law, she began to see how bias in policing and courts was not just a collection of bad decisions by individuals.

It was part of a larger arrangement that functioned predictably: arrest, conviction, and the permanent downgrade of citizenship for huge numbers of people of color. In her account, the system resembles older forms of racial control not because it uses the same language, but because it produces similar outcomes—separation, stigma, and exclusion.

She traces the groundwork for this shift through the rise of “law and order” politics. In the late 1950s and 1960s, as the Civil Rights Movement challenged segregation, many white politicians reframed demands for equality as threats to public safety.

Protest and civil disobedience were treated as criminal behavior, and integration was presented as a recipe for chaos. After major social unrest in the 1960s, fear of disorder became a powerful political resource.

Conservatives learned to translate open racial hostility into coded language about crime, welfare, and “states’ rights.” This approach helped pull many working-class and Southern white voters away from the Democratic coalition that had held together through the New Deal era, reshaping national politics around racial resentment expressed through “race-neutral” terms.

Alexander argues that the War on Drugs expanded from this political foundation. She describes it as a strategy that gained momentum even before the crack epidemic became a national crisis.

Under President Reagan, the federal government elevated drug enforcement dramatically, pouring money into policing and prosecution while reducing support for education and treatment. Media campaigns amplified frightening images of crack use and drug dealing in Black neighborhoods, feeding a public sense of emergency.

Legislators responded with harsh laws, including mandatory minimum sentences and penalty structures that punished crack cocaine far more severely than powder cocaine. These policies passed with broad bipartisan support, and later administrations—Republican and Democratic—continued the escalation.

According to Alexander’s argument, the result was not simply more arrests; it was the construction of a system designed to produce an identifiable class of people who could be controlled and excluded.

A central point in the book is the mismatch between drug behavior and drug punishment. Alexander emphasizes that studies repeatedly showed similar rates of drug use and sales across racial groups, yet Black communities were targeted for enforcement.

Police tactics concentrated surveillance and stops in segregated neighborhoods, so drug activity there became far more visible to law enforcement than similar activity in white areas. As arrests accumulated, the legal system turned those arrests into long-term social status.

She highlights how, in many places, Black men ended up imprisoned for drug crimes at vastly higher rates than whites, and in some urban communities a large share of young Black men carried criminal records. For Alexander, this is the defining feature of the “colorblind” era: the rules appear neutral, but the design and enforcement produce racial sorting.

She places the growth of prisons in a larger national context. The U.S., she argues, chose punishment on a scale unlike other Western democracies.

Crime rates alone cannot explain the rise. Instead, policy choices did: expanded police funding, prosecutors armed with tougher statutes, plea bargaining pressures, and sentencing rules that removed discretion and increased time served.

The explosion in incarceration created what she portrays as a self-reinforcing machine, with institutions and local economies adapting to prison growth and developing an interest in maintaining it.

Alexander then focuses on what happens after release, insisting that the prison term is only part of the punishment. The criminal label triggers a second, lasting sentence: legal discrimination in employment, housing, education, and access to public benefits.

She describes voting restrictions as one of the clearest examples of civic banishment. In most states, people in prison cannot vote, and many remain disenfranchised after release.

Even those who are technically eligible often face confusing rules, fees, and paperwork barriers that keep them out, and many fear contact with authorities because of how easily supervision violations can return them to jail. Through stories like Clinton Drake, a veteran barred from voting because of unpaid court costs, she connects modern barriers to older tactics that suppressed Black political power.

Beyond formal restrictions, she emphasizes stigma. The shame attached to incarceration spreads beyond the individual to families and whole neighborhoods.

Drawing on social research, she describes how families often hide imprisonment from friends, churches, and employers, creating isolation and silence. In her telling, the stigma is so severe that it shapes identity: some young men, relentlessly treated as suspects, begin to adopt the “criminal” image as a form of defiance and belonging.

Alexander argues that this coping strategy is understandable but damaging, because it strengthens public stereotypes and gives the system a cultural story that seems to justify continued punishment. She also criticizes how entertainment markets profit from exaggerated images of Black criminality, reinforcing a loop in which stereotypes help drive policy and policy then creates conditions that appear to confirm stereotypes.

Alexander challenges the idea that Black communities broadly supported the punitive turn. She argues that many Black Americans wanted safety from violence but were offered only police and prisons instead of jobs, stable housing, good schools, and treatment.

This creates what she describes as a painful bind, especially for Black women trying to protect families while knowing that the same system can swallow their sons and partners. Cooperation with harsh enforcement can become a survival strategy, not a sign of endorsement.

She also critiques mainstream civil rights leadership for treating mass incarceration as a side issue for too long. In her view, many organizations focused on symbolic or professional gains while avoiding the morally and politically difficult task of defending people branded criminals.

Legal strategies and incremental reforms, she argues, cannot defeat a system rooted in public consensus and racial denial. She points to moments of visible racial outrage—such as the protests around the Jena Six—as evidence that Americans respond more readily to overt symbols of racism than to routine, bureaucratic injustice that hides behind neutral language.

In the end, Alexander argues that small reforms driven by cost savings or modest sentencing adjustments will not dismantle the caste structure. The system, as she describes it, is protected by incentives and institutions that benefit from enforcement and incarceration, as well as a broader culture that accepts the criminal label as a reason to withdraw empathy.

She calls for a mass movement that confronts race directly, rejects the myth that America is “post-racial,” and rebuilds a politics grounded in human dignity. In her framework, the antidote is not denial or distance from “criminals,” but solidarity—refusing to treat any group as disposable, and insisting that full citizenship cannot depend on who has been marked by the system.

Key People

Jarvious Cotton

Jarvious Cotton serves as a powerful emblem of the intergenerational continuity of racial disenfranchisement in The New Jim Crow. His inability to vote because of a felony conviction connects him directly to his ancestors who were denied the same right under slavery, Jim Crow laws, and various forms of racial suppression.

Through Cotton’s story, Michelle Alexander exposes how the mechanisms of exclusion have evolved rather than disappeared. Cotton is not portrayed as an individual anomaly but as a living testimony to a systemic design that redefines racial control through legal means.

His character acts as a bridge between past and present, linking the explicit racism of earlier eras to the covert racialized punishment of modern America. Alexander uses Cotton’s experience to personalize her central argument—that mass incarceration is not a coincidence of policy but a deliberate restructuring of racial hierarchy.

Michelle Alexander (The Author and Narrator)

Michelle Alexander herself emerges as a central figure in The New Jim Crow, both as narrator and as a moral witness undergoing transformation. Initially skeptical of the claim that mass incarceration represented a new racial caste, she begins her journey as a civil rights lawyer convinced that systemic inequities were rooted primarily in class and education.

Her intellectual evolution—from disbelief to advocacy—reflects the broader awakening she seeks in her readers. Through her experiences at the ACLU, she confronts evidence that racial bias is not incidental but institutionalized within the criminal justice system.

Alexander’s honesty about her own misconceptions lends credibility and humility to her argument. She becomes a guide who translates data and policy into a moral reckoning, urging society to confront uncomfortable truths about race and justice.

Her role transcends scholarship; she is both analyst and activist, articulating a vision of empathy and collective resistance against the myths of colorblindness.

Jarvious Cotton’s Family Line

Beyond Cotton himself, his forefathers—though unnamed—form a generational chain symbolizing the continuity of racial subjugation. Each ancestor embodies a distinct phase of America’s racial history: slavery, the Jim Crow South, and the current era of mass incarceration.

Their presence in the narrative underscores that racial control has always adapted to new social contexts. Alexander portrays these men not as isolated victims but as inheritors of a legacy of disenfranchisement that transforms in form but not in function.

Through this lineage, the book illustrates how systemic racism persists through legal innovation and public consent. The Cotton family thus becomes both historical metaphor and documentary evidence of the nation’s cyclical oppression.

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan stands as one of the political architects of the mass incarceration system in The New Jim Crow. His presidency marks the institutional expansion of the War on Drugs, which Alexander characterizes as a racially coded campaign disguised as a public safety initiative.

Reagan’s rhetoric of “law and order” and his imagery of “welfare queens” and “predators” resonated deeply with white anxieties while appearing race-neutral. His policies redirected federal resources toward punitive drug enforcement, disproportionately targeting Black communities.

Alexander presents Reagan not as a villain acting alone but as a representative of a political movement that weaponized fear for electoral gain. His administration’s manipulation of media narratives and policy priorities solidified mass incarceration as a bipartisan orthodoxy, embedding racial control into the framework of American governance.

Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon’s role precedes Reagan’s, laying the ideological foundation for what Alexander calls the “New Jim Crow.” Nixon’s Southern Strategy transformed racial resentment into political capital by linking civil rights activism with crime and social disorder. His campaign’s emphasis on “law and order” rebranded segregationist logic into coded language acceptable in post–Civil Rights America.

Nixon’s private admissions—later revealed by his aides—confirm that this rhetoric was a deliberate appeal to white voters discontent with racial integration. In Alexander’s analysis, Nixon’s genius was not policy innovation but rhetorical manipulation; he taught future politicians how to sustain racial hierarchy under the guise of neutrality.

His presidency thus marks the birth of a new political consensus in which race could be discussed only through the language of crime.

Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton embodies the tragic culmination of bipartisan complicity in mass incarceration. In The New Jim Crow, he represents the Democratic Party’s surrender to “tough-on-crime” politics as a strategy to win back white voters alienated by earlier civil rights reforms.

Clinton’s policies—the 1994 Crime Bill, the “three strikes” law, and welfare reform—expanded prisons, militarized policing, and criminalized poverty. Alexander portrays Clinton as a figure whose actions, though framed as pragmatic centrism, inflicted devastating harm on Black communities.

His personal decision to oversee an execution during his campaign symbolizes his alignment with punitive politics. Clinton’s reforms institutionalized lifelong penalties for ex-offenders, from housing bans to employment discrimination, ensuring that racialized punishment persisted even after release.

Willie Johnson

Willie Johnson represents the lived consequences of the system that Alexander condemns. A former prisoner, he experiences the endless cycle of rejection, homelessness, and despair caused by the stigma of a felony record.

Through his story, The New Jim Crow reveals how punishment extends far beyond prison walls, shaping every aspect of an individual’s life. Johnson’s narrative is not one of moral failure but of systemic betrayal—he is a man trapped in a society that has already judged him irredeemable.

His testimony underscores Alexander’s claim that the “prison label” functions as a modern form of racial branding, relegating millions to second-class citizenship. Johnson’s endurance, despite humiliation and exclusion, humanizes the abstract statistics of incarceration and forces readers to confront the emotional and psychological toll of perpetual marginalization.

Clinton Drake

Clinton Drake’s story adds another dimension to Alexander’s portrayal of racialized disenfranchisement. A Vietnam veteran permanently stripped of his voting rights over unpaid court fines, Drake symbolizes the convergence of patriotism, sacrifice, and systemic betrayal.

Despite having served his country, he is rendered politically invisible by laws that echo the poll taxes of the Jim Crow era. His character exposes the cruel irony of a nation that demands loyalty from those it refuses to recognize as full citizens.

Through Drake, Alexander demonstrates how the criminal justice system perpetuates both economic and racial oppression by attaching civic penalties to poverty. His disenfranchisement is not just a personal tragedy but a political statement about how democracy is weaponized to exclude the already marginalized.

Themes

Racial caste through criminalization

Jarvious Cotton’s inability to vote is framed less as a personal misfortune and more as a family pattern that keeps repeating under different legal names, which captures how The New Jim Crow treats mass incarceration as a status system rather than a set of isolated punishments. The point is not simply that prisons expanded, but that the “criminal” label became a substitute for old racial categories once explicit discrimination lost legal legitimacy.

When a person is marked a felon, society gains permission—often written directly into law—to deny them work, housing, loans, public benefits, education opportunities, and basic civic standing. What makes this theme powerful is the argument that confinement is only one stage; the caste is built in what comes after.

The system relies on the routine use of background checks, blanket bans, and discretionary “character” judgments that sound neutral but operate predictably against communities already targeted by policing. In this framework, discrimination becomes socially acceptable again because it is redirected away from race and toward “crime,” even when enforcement patterns are saturated with racial bias.

The book’s underlying logic is that the United States did not end racial hierarchy; it revised the mechanism. The caste structure is sustained by public narratives that define those captured by the system as people who chose their fate and therefore deserve exclusion.

That moral story—criminals as “others”—does the heavy lifting, because it encourages even well-meaning observers to treat permanent penalties as normal consequences rather than as a political choice about who counts as a full member of society. The theme also stresses continuity: slavery and Jim Crow were not only cultural attitudes but legal regimes that organized labor, rights, and belonging, and mass incarceration becomes the modern method of sorting people into protected and disposable categories while preserving the nation’s self-image as fair.

Colorblind language as a cover for racial control

The summaries repeatedly show how racial meaning can be carried by terms that never mention race, turning “colorblindness” into an operating principle rather than a moral achievement. “Law and order,” “states’ rights,” “crime,” and “welfare dependency” function as coded signals that reassure audiences who want racial hierarchy without the stigma of open racism.

The theme is not that every voter consciously embraced hatred, but that political language was engineered to convert racial anxiety into policy demands that appeared race-neutral. Once the public conversation is structured around disorder and punishment, it becomes easy to justify extraordinary enforcement in Black neighborhoods while maintaining the claim that the system is simply responding to crime.

This theme matters because it explains why reform is so difficult: if racism is imagined only as explicit slurs or segregated signs, then a system built through neutral statutes and bureaucratic procedures can be defended as objective even while producing sharply racial outcomes. The book’s argument treats colorblindness as a cultural permission slip for indifference, because it instructs people not to talk about race even when race predicts who will be stopped, searched, charged, and labeled.

It also creates a trap for public debate: critics are pressured to prove intentional bias in each decision rather than confronting the cumulative design of the system. In that environment, statistical disparities are dismissed as unfortunate side effects of “bad choices” instead of being read as evidence of targeted control.

The theme also ties to the symbolism of Black exceptionalism—such as pointing to prominent Black success or a Black president—as proof that equal opportunity exists. That symbolism can silence discussion by implying that remaining inequality must be individual failure.

The book’s insistence is that a society can congratulate itself on formal equality while still using neutral rhetoric to rationalize a racial order, because the absence of racial vocabulary does not mean the absence of racial function.

“Law and order” politics and the bipartisan construction of punishment

The narrative of political realignment shows punishment expanding not as an accidental response to crime but as a sustained electoral project that matured across parties and decades. Beginning in the backlash to civil rights activism, “law and order” served as a way to recast demands for equality as threats to public safety, transforming protest into “criminality” and framing integration as a cause of chaos.

That framing created a pathway for politicians to win anxious voters by promising crackdowns, with race operating as the unspoken link between social change and fear. The theme becomes even sharper in the shift from Republican strategy to bipartisan consensus.

Once punitive policies proved electorally useful, Democrats adopted the same posture to avoid the label of being “soft,” producing a political environment where competing parties raced to prove toughness through policing budgets, mandatory minimums, and prison expansion. The result is a system that cannot be explained by a single leader or a single era; it is a cross-administration buildout of enforcement capacity, sentencing severity, and collateral penalties.

The book also highlights how media campaigns and sensational stories created public urgency that politicians could convert into legislation, meaning the public’s sense of emergency often preceded the facts. Harsh crack sentencing, for example, is presented as a policy choice made under panic, then protected by the political cost of appearing lenient.

This theme also reveals how punishment became a substitute for social investment: when leaders promised security through arrests rather than through jobs, schools, and health care, they reinforced a cycle in which communities harmed by poverty were further destabilized by the removal of large numbers of men and the long-term exclusion of those branded felons. The bipartisan nature of the outcome is central to the theme’s warning: if the political center treats mass incarceration as normal governance, then modest reforms can be absorbed without changing the underlying commitment to control, and the machinery simply adjusts to new rules.

The War on Drugs as strategy, not public safety

The summaries frame the drug war as a project that gained momentum through political calculation, public relations, and institutional incentives rather than through a careful response to drug harm. Declaring a national war in 1982—before the crack crisis reached full visibility—supports the claim that the campaign was already underway as a tool of governance, later justified by media-driven panic.

This theme stresses how moral emergencies are manufactured: images of “crack dealers” and “crack babies” created a sense of existential threat, which made extreme policies appear reasonable and even compassionate. Yet the central contradiction remains that drug use and sales were reported as broadly similar across racial groups while enforcement concentrated on Black neighborhoods, suggesting that the target was not the drug but the people.

The theme also addresses how institutions adapt to the incentives of war: agencies reallocate resources toward street-level drug enforcement because budgets, promotions, and political praise follow visible arrests, while treatment and education are neglected because their benefits are harder to dramatize. The drug war’s architecture also expands discretion—traffic stops, searches, plea deals, and charging decisions—creating many points where bias can operate without being easily proven.

That discretion helps explain why disparities can become enormous even without overtly racist laws. Another layer of the theme is the relationship between foreign policy, domestic neglect, and community devastation, as the summaries reference government admissions related to drug flows connected to foreign conflicts.

Whether or not every detail becomes the focus, the broader point is that Black communities bore the consequences of decisions made far from their streets, while the public narrative blamed those same communities for the damage. In The New Jim Crow, the drug war is presented as the gateway into a long-term social position: once swept in for low-level offenses, many are pressured into guilty pleas and then carry the felony mark for life, turning a time-limited sentence into a permanent reduction in rights and opportunity.

Civil death through disenfranchisement and legalized exclusion

Voting bans, fines, fees, and bureaucratic hurdles function as a modern method of political containment, making citizenship conditional long after a person has served their sentence. The theme emerges in the contrast between U.S. policy and other democracies, and even between American states, showing that disenfranchisement is not inevitable; it is chosen.

By tying rights restoration to administrative steps, court costs, and repayment schedules, the system creates a paywall around civic participation that resembles older tactics used to shrink the electorate. The example of someone barred from voting over less than a thousand dollars demonstrates how small financial obstacles can carry enormous democratic consequences, especially when concentrated in communities already burdened by poverty and heavy policing.

This theme also captures the emotional and psychological dimension of exclusion: even when technically eligible, many fear registering because they assume any contact with the state could trigger surveillance or punishment. That fear is not irrational in a context where supervision can be strict, rules are complex, and mistakes carry harsh penalties.

The book treats this as a form of social conditioning, where generations learn that political participation is dangerous or futile, echoing earlier eras when violence and intimidation policed the ballot box. Beyond voting, the theme extends to employment and housing discrimination that is explicitly permitted once the “criminal” label is applied.

The result is a feedback loop: exclusion from jobs and stable housing increases vulnerability, which increases contact with the system, which deepens exclusion. Instead of rehabilitation, the legal structure promotes permanent instability.

The theme’s sharpest claim is that this is a kind of civil death: the state continues to punish through denial of belonging, and society accepts it because the target is defined as a criminal rather than as a neighbor. In this sense, the system relies on law to turn social rejection into official policy, creating a durable underclass without needing to mention race.

Stigma, shame, and the reshaping of identity under constant surveillance

The summaries emphasize that the most enduring punishment often arrives as stigma—quiet, routine, and everywhere. Being labeled a felon or treated as a suspect from childhood alters how people move through daily life: job interviews become interrogations, housing applications become confessions, and even family relationships can be strained by humiliation.

Research described in the summary rejects the stereotype that incarceration is worn proudly; instead, it points to secrecy, silence, and an ongoing effort to hide the truth from friends, neighbors, and employers. Families carry the weight too, concealing a loved one’s incarceration to avoid judgment and moral blame, sometimes even within religious communities that might otherwise be sources of support.

The idea of “pluralistic ignorance” is crucial here: when everyone hides their pain, each person assumes they are alone, which weakens collective response and deepens isolation. The theme also explains why some young men embrace the criminal identity that society projects onto them.

When institutions treat a teenager as dangerous regardless of his behavior, adopting the label can feel like reclaiming control—turning imposed shame into a defiant persona. But the book’s argument, as reflected in the summaries, is that this coping strategy can become self-harming because it reinforces the very stereotypes used to justify aggressive policing and harsh sentencing.

The commercialization of “gangsta” imagery intensifies this dynamic by rewarding performances of criminality, often for audiences who consume these images as confirmation of racist assumptions. The comparison to minstrel traditions underscores the theme’s moral tension: economic survival and cultural expression can be pushed into roles that maintain oppression.

What makes this theme central is that stigma is not only personal; it is political. A population burdened by shame is easier to exclude, easier to ignore, and less able to organize.

The book’s insistence is that the “criminal” label functions like a social scarlet letter that authorizes constant suspicion while encouraging the public to treat the harm as deserved.

Economic abandonment and the production of “disposable” communities

Deindustrialization and the loss of stable urban employment form a backdrop that changes how the state responds to poverty: instead of building opportunity, it builds enforcement. This theme links economic restructuring to the rise of mass incarceration by showing how joblessness and failing schools are treated not as crises requiring investment but as conditions requiring containment.

When communities are offered police and prisons as the primary tools of governance, punishment becomes a substitute for economic policy. The summary’s reference to a shift from exploiting Black labor to treating Black people as irrelevant captures a bleak implication: if a population is no longer needed for economic growth, the moral urgency to protect their well-being weakens, and harsh control becomes easier to justify.

The theme also explains the “dual frustration” felt in many Black communities—especially among women—who want relief from violence yet fear that calling for state intervention will bring raids, arrests, and life-changing felony records for family members. That dilemma exposes how limited the menu of options has become: safety is pursued through coercion because the state has withdrawn the resources that would make safety sustainable.

The theme further highlights the role of economic interests that grow around the punishment system itself—jobs tied to prisons, budgets tied to drug enforcement, and industries tied to surveillance and detention. When millions of livelihoods depend on the continuation of punitive policies, reform becomes not only a moral debate but also a conflict over economic survival for those benefiting from the status quo.

This helps explain why small policy shifts are often absorbed without reducing the system’s overall reach. The argument presented in The New Jim Crow is that real change must disrupt these incentives and rebuild the social supports that make mass criminalization unnecessary.

Without that shift, poverty remains criminalized, communities remain destabilized, and the system’s growth is treated as normal governance rather than as a choice to manage inequality through punishment.

The limits of mainstream civil rights strategies and the need for a mass moral movement

The summaries describe a persistent gap between the scale of harm and the scale of organized response, especially from institutions historically associated with racial justice. This theme is not a simple critique of intention; it is an argument about strategy, professional incentives, and public comfort.

When advocacy becomes dominated by courtroom litigation and policy expertise, it can lose the ability to mobilize broad moral pressure, particularly for people who have been labeled criminals and therefore are politically unpopular. Civil rights organizations may prefer cases featuring “innocent” victims or sympathetic plaintiffs because those stories attract donors and reduce backlash, but that preference leaves millions of people—who have been swept up through plea bargains, targeted policing, and low-level drug enforcement—outside the circle of defendable humanity.

The theme also explains why visible symbols of old racism can generate mass protest while routine practices of the new system remain unchallenged. A noose provokes immediate recognition; a drug arrest for a minor offense, followed by years of exclusion, is easier to overlook because it is processed as normal law enforcement.

The book’s argument is that the system survives on public consent, and consent is maintained through denial—especially the comforting belief that society is now post-racial. In that climate, reforms that focus only on reducing sentences or improving procedures risk leaving the caste structure intact, because the core social meaning of the “criminal” label remains unchallenged.

The theme insists that dismantling the system requires more than technical fixes; it requires a movement that changes what the public believes about crime, punishment, and belonging. That includes confronting the fear of defending stigmatized people and rebuilding solidarity across race and class around shared vulnerability to state power.

The call is for a human rights orientation that treats dignity as non-negotiable, refusing to trade the safety of some communities for the civic death of others.

Compassion, solidarity, and “color consciousness” as the path out

The concluding moral direction presented in the summaries is grounded in a refusal to treat people with criminal records as disposable. The theme does not ask for naivety about harm; it asks for a different understanding of accountability that does not rely on lifelong exclusion.

“Hate the crime, but love the criminal” is presented as an ethical pivot away from shame-based governance and toward a recognition that people are more than their worst act or the most aggressive charge a prosecutor could secure. This theme also challenges the idea that fairness comes from never mentioning race.

The argument is that refusing to talk about race protects the status quo because it prevents society from seeing patterns that are obvious to those living inside them. “Color consciousness,” as described, means acknowledging history and current realities plainly so that remedies match the scale and shape of the harm.

Compassion here is not only interpersonal kindness; it is a political stance that insists on restoring rights, removing structural barriers, and reinvesting in the conditions that make survival possible—education, treatment, stable work, and housing. Solidarity is equally central: the system’s endurance depends on dividing groups through fear, resentment, and “racial bribes,” offering psychological comfort to some at the cost of others’ exclusion.

The theme argues that real change requires rejecting those bargains and building coalitions that can withstand the predictable attacks that come with defending unpopular people. It also suggests that future generations will judge the current era the way we now judge past racial regimes: as a moral failure sustained by normalcy and silence.

In that sense, the theme is a call to replace indifference with active recognition—seeing the humanity of those branded criminals, and treating their return to full citizenship not as charity but as a democratic requirement.