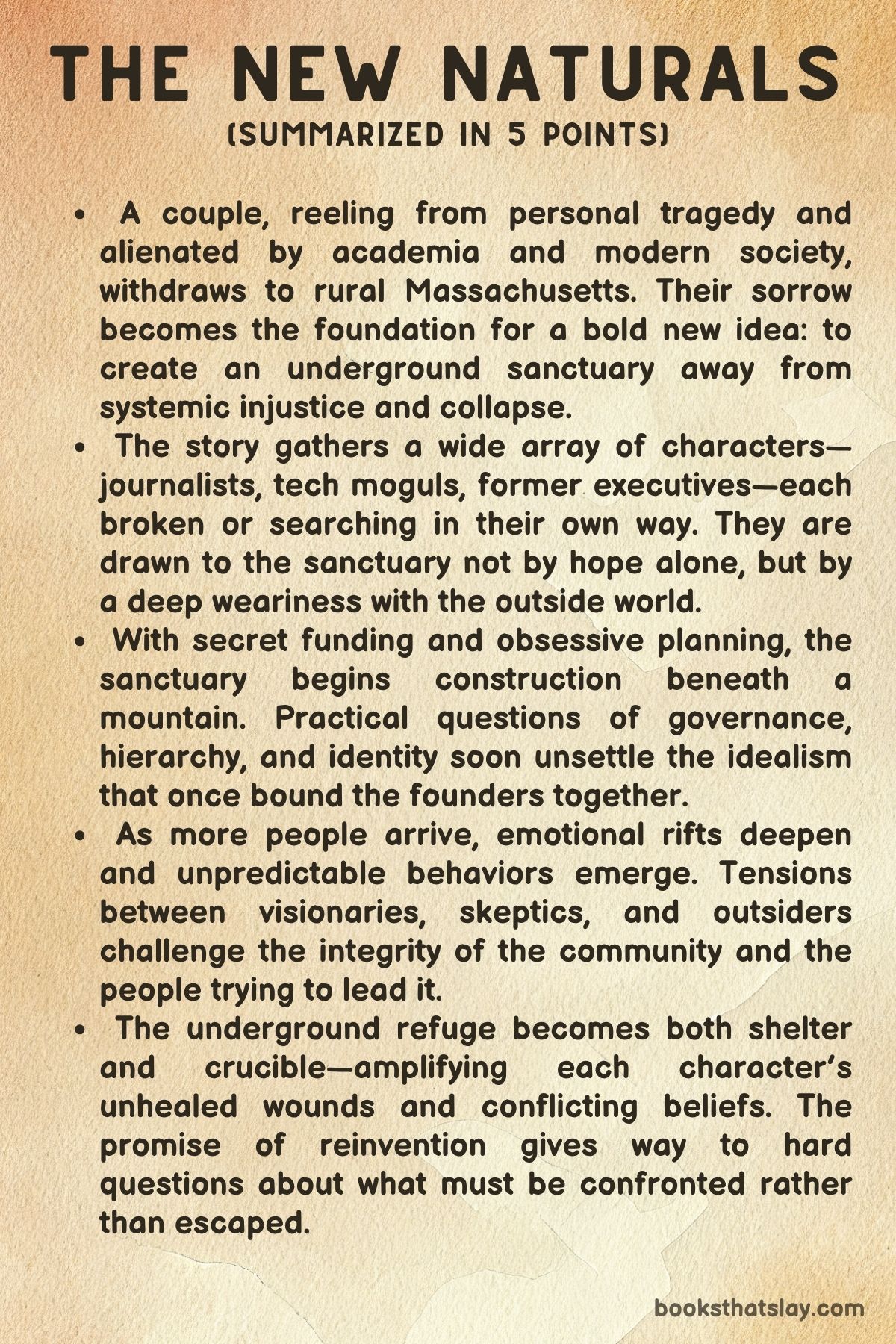

The New Naturals Summary, Characters and Themes

The New Naturals by Gabriel Bump is a fiercely imaginative and psychologically layered novel that explores the emotional fallout of modern disillusionment through a radical experiment in community-building.

Set in a near-contemporary United States beset by racial inequity, environmental decay, and spiritual detachment, the story centers on a grieving couple who attempt to create a utopia underground.

Bump crafts a sprawling ensemble of broken idealists, disillusioned professionals, and quietly desperate outsiders drawn to this subterranean refuge.

Through its shifting perspectives and surreal flourishes, the novel interrogates the cost of hope, the messiness of reinvention, and the fragile line between visionary dreams and emotional collapse.

Summary

The New Naturals opens with Gibraltar and Rio, a married Black academic couple in Boston, growing disillusioned with institutional racism and the hollowness of liberal academia.

Expecting their first child, they become consumed by a desire to escape what they perceive as a broken world.

Rio, plagued by surreal visions and emotional instability, imagines a sanctuary for people like them—an underground haven where the marginalized can live outside the toxic constructs of modern society.

Their dreams take a sharper edge after the sudden death of their newborn daughter, Drop, which plunges them into overwhelming grief and propels their vision from abstract idea to concrete mission.

They leave their academic lives behind and relocate to a remote part of western Massachusetts.

Rio becomes singularly focused on building a hidden, self-sustaining underground community.

She immerses herself in plans, maps, and recruitment ideas.

Gibraltar, more passive and uncertain, supports her despite misgivings.

Eventually, they begin to call their concept “The New Naturals,” a nod to reclaiming a more honest, humane way of life.

Parallel narratives soon unfold.

Sojourner, a burnt-out journalist haunted by systemic injustice and emotional emptiness, undergoes her own psychological spiral.

After hallucinating in the woods and leaving behind her boyfriend and job, she wanders in search of meaning and eventually finds herself connected to the New Naturals.

Meanwhile, a wealthy and mysterious figure known as “The Benefactor” becomes enamored with the idea and decides to fund the project.

She sets up elite planning boards and leverages her tech-world wealth to begin excavating a hidden facility in the mountain.

With resources and momentum in place, the sanctuary begins to take form, attracting a motley collection of disaffected people: academics, dropouts, former activists, and lost souls seeking renewal.

Among the first arrivals is Bounce, a volatile young man whose presence disrupts the tentative harmony.

His emotional volatility and contempt for order make him both a liability and a mirror to the community’s underlying instability.

Gibraltar grows more alienated.

While Rio becomes increasingly revered—more prophet than partner—he drifts toward invisibility.

He cooks, fixes things, and tries to belong, but he no longer recognizes his own voice in the movement.

Meanwhile, Elting and Buchanan, two older men with checkered pasts in business and leadership, bring a sharper, more cynical perspective.

Their conversations often orbit philosophical doubts, emotional numbness, and the sense that the New Naturals is less salvation than spectacle.

The sanctuary expands, but so does the emotional turbulence.

Sojourner and Bounce develop an intense, self-destructive relationship that reflects the broader volatility simmering beneath the community’s idealism.

Tensions build around leadership, logistics, and the question of whether this world is truly any different from the one they tried to leave.

Rio drifts further into abstraction, speaking in riddles and losing touch with her relationships.

Her transformation from grieving mother to mystical leader renders her both revered and estranged.

In its final section, the novel focuses on Elting and Buchanan, who function as philosophical foils to the utopian dream.

They question the community’s premise, recognizing it as an unsustainable refuge for unresolved pain.

Their detached, often nihilistic commentary underscores the fragility of the entire project.

As tensions rise within the Mountain, their presence marks a spiritual unraveling.

There is no fiery collapse—just a quiet awareness that utopia cannot seal off the human condition.

The novel ends on a note of sobering reflection.

What began as a visionary attempt to escape a broken society becomes, instead, a mirror of its complexities.

The New Naturals may be physically hidden, but the pain, contradictions, and emotional ruins they sought to escape still reside within them.

Gabriel Bump’s narrative leaves readers with a haunting realization: that no matter how deep underground we go, we bring our ghosts with us.

Characters

Rio

Rio is the spiritual nucleus of The New Naturals, a visionary, a grieving mother, and an increasingly messianic figure. Her journey begins in the world of academia, where she is battered by racial microaggressions and the empty inclusivity of progressive institutions.

The stillbirth of her daughter, Drop, catalyzes a profound philosophical transformation in her. Rather than collapse, she channels her grief into building a utopia underground—an emotional and physical retreat from the world’s injustices.

Rio’s visionary zeal becomes both a source of inspiration and concern. As the novel progresses, she loses touch with her husband and, eventually, with herself.

Her speeches become abstract and mystical. While she draws others into her orbit, she grows increasingly isolated.

She is the prophet whose vision costs her intimacy, clarity, and peace. In the end, Rio represents the tragic potential of ideological purity—its power to galvanize and its danger to devour.

Gibraltar

Gibraltar begins the novel as a committed partner and co-dreamer alongside Rio. A Black academic like his wife, he too feels disillusioned by the world they inhabit, but his response is quieter, more grounded.

In the wake of Drop’s death, he follows Rio into the unknown. But his enthusiasm wanes as their underground community takes shape.

Gibraltar becomes the invisible backbone of the community—cooking, repairing, nurturing. As Rio assumes the role of leader and oracle, he slips into obsolescence.

His crisis is one of identity and purpose. He once envisioned himself as a public intellectual, but now he is a ghost within his own dream.

Gibraltar’s emotional retreat mirrors the dangers of a movement that centralizes visionary figures at the cost of shared humanity. He is a man mourning not just his daughter, but his marriage, his relevance, and perhaps his very selfhood.

Sojourner

Sojourner is introduced as a burnt-out local journalist whose emotional implosion parallels Rio’s earlier breakdown. Alienated from her partner Rascal and disgusted by public indifference to environmental injustice, she begins hallucinating in the woods.

She abandons her job and relationship to search for meaning. Her arrival at the Mountain injects a fresh instability.

Her connection with Bounce is both passionate and destructive—a romance forged in mutual damage rather than healing. Sojourner represents those drawn to radical spaces not by ideological conviction but by emotional desperation.

Her presence challenges the notion that utopia can save anyone who is not also trying to save themselves. She is not a builder but a seeker, and her volatility threatens the very structure she has entered.

Bounce

Bounce is the embodiment of chaos. Brash, unpredictable, and volatile, his arrival at the Mountain shatters any illusion of serene idealism.

He is both a critic and a mirror, forcing others to confront the contradictions in their utopian project. His bond with Sojourner is electric, co-dependent, and at times destructive.

Bounce is not invested in rules or vision. He exists to expose hypocrisies, push buttons, and rupture comfort zones.

He is the type of figure every utopia attracts and fears—the one who refuses to conform, but whose very presence ensures the community remains alive and uncomfortable. Bounce is the narrative’s wild card, showing that utopia, like the real world, cannot escape the anarchic pull of human behavior.

Elting

Elting is a fallen executive—a man whose life of professional success disintegrated under the weight of personal failure and addiction. He arrives at the Mountain as a shell of himself, seeking neither leadership nor salvation but a kind of passive refuge.

Elting’s flashbacks paint a portrait of emotional abandonment and psychological ruin. As the story progresses, his presence becomes more sinister—part ghost, part philosopher.

He engages in cryptic dialogues with Buchanan, dissecting the project’s flaws and quietly predicting its demise. Elting symbolizes the emotional wreckage that utopias try to exclude or fix.

His journey suggests that trauma, unexamined and unhealed, will always resurface, no matter how deep one goes underground.

Buchanan

Buchanan is a charismatic, manipulative intellectual whose primary role in the novel is that of provocateur. Where Rio builds and Gibraltar doubts, Buchanan observes and critiques.

His friendship with Elting is complex—marked by a blend of loyalty, rivalry, and shared nihilism. He is one of the few characters who never fully buys into the New Naturals’ dream.

Instead, he treats the entire project as an experiment destined for collapse. His conversations are laced with sarcasm, insight, and philosophical disillusionment.

Buchanan represents the seductive pull of cynicism in movements built on idealism. He is the mind that won’t follow the heart, the logician who sees utopia as theater.

His presence ensures the reader never forgets the frailty beneath the Mountain’s concrete.

Themes

Grief as Catalyst for Reinvention

Grief in The New Naturals is not a static emotional wound but a dynamic force that reconfigures the architecture of reality for its characters. The death of Drop, the infant daughter of Gibraltar and Rio, marks the psychic fracture upon which the rest of the narrative is constructed.

Rather than immobilizing the couple, this loss becomes the impetus for a radical reimagining of life itself. Rio, especially, channels her anguish into an obsessive vision for an underground sanctuary—a place where the marginalized can escape the cruelty of the surface world.

Her grief distorts her perception of the world, making its injustices unbearably sharp and fueling her conviction that only complete withdrawal can provide salvation. Gibraltar, too, undergoes transformation, though more quietly; his role as a father and partner is gutted, and he floats through the project searching for utility and validation.

This theme suggests that grief does not only provoke sorrow—it invites ideological extremism, compulsion, and ultimately, a kind of spiritual intoxication. The book does not romanticize this transformation but reveals how grief can forge movements, alter relationships, and distort one’s understanding of what it means to heal.

As more characters join the New Naturals, they too are often fleeing loss or emptiness, and the community itself becomes a monument to unresolved grief. Grief in the novel is not a closed emotional system—it leaks into politics, architecture, relationships, and identity.

Rather than being resolved, it becomes the foundation of a new, experimental world that seeks healing through separation but risks replicating the very conditions it tried to escape.

Utopia and Its Discontents

The pursuit of a utopia in The New Naturals is characterized not by optimism but by weariness, dread, and an overwhelming sense that the world above cannot be salvaged. This utopia is not built on dreams but on exhaustion—with academia, with systemic racism, with failed activism, and with the emotional fatigue of existing in a hostile world.

The underground community represents an extreme response to disillusionment: a place where its founders and followers can start over, removed from the corruption and disappointment of the surface. However, the novel systematically dismantles the idea that utopia can be born from escape.

The further the characters descend—physically and emotionally—the more apparent it becomes that trauma, hierarchy, and conflict persist even in isolation. Rio’s vision, while idealistic, becomes increasingly autocratic and mystical, alienating her from Gibraltar and other members of the community.

The Benefactor’s financial control and quiet surveillance suggest that even in this new world, power structures cannot be undone, only reconfigured. Tensions over leadership, ideology, and inclusion arise quickly, and the project begins to buckle under the pressure of human complexity.

Rather than a sanctuary, the underground compound becomes a pressure chamber, mirroring the same dynamics it sought to avoid. This theme critiques the very foundation of utopian thinking, exposing how ideals built on trauma and fear may replicate exclusionary logic under the guise of sanctuary.

The novel ultimately suggests that utopia is not a place but a question—one that forces individuals to reckon with what they carry and what they leave behind.

Isolation as Illusion of Safety

The underground setting of the New Naturals’ sanctuary functions as both literal refuge and psychological metaphor, representing the illusion that isolation can offer protection from emotional or societal harm. Rio and Gibraltar’s retreat from the surface world is initially portrayed as an act of visionary defiance—a refusal to participate in systems that continually marginalize and endanger them.

Yet the deeper they embed themselves in the mountain, the more apparent it becomes that physical distance does not equate to emotional or ideological safety. Rio, despite her intentions, becomes increasingly isolated even from those closest to her, including Gibraltar.

Her vision grows more cryptic, her communication more performative, and her leadership more authoritarian. Gibraltar, surrounded by people yet unseen and unheard, embodies the loneliness that festers beneath the communal surface.

For newcomers like Sojourner and Bounce, the compound offers temporary distraction but not the connection or grounding they crave. Their interactions become frenzied and self-destructive, underlining the failure of geography to address emotional instability.

Elting and Buchanan, older and more skeptical, remain emotionally uninvested and observe the community with a detachment that borders on contempt. Their very presence in the sanctuary exposes the flaw in its foundational logic: that emotional burdens and systemic trauma can be left behind simply by relocating.

The novel thus argues that isolation, rather than a solution, is often a deferral. It provides the illusion of safety while allowing deeper fractures to go unacknowledged.

The mountain, far from a fortress, becomes a mirror that reflects rather than shields its inhabitants from the truths they fear.

The Fragility of Leadership and Vision

Leadership in The New Naturals is not marked by confidence or charisma but by internal erosion. Rio, who originates the community’s vision, begins as a compelling force—a grieving mother turned revolutionary thinker.

Yet as the project grows and attracts followers, her role transforms from inspired creator to isolated prophet. Her speeches become less grounded and more abstract; her decisions grow unilateral, often unexamined.

Rather than building consensus, she becomes a figurehead—admired, misunderstood, and increasingly detached from the reality around her. Gibraltar’s diminishing role exemplifies a different kind of leadership failure: passive, unsure, and burdened by feelings of inadequacy.

He becomes a caretaker rather than a co-architect, quietly slipping into the background as his partner ascends. The Benefactor, who bankrolls the operation, wields a different form of influence—financial and invisible.

Though absent, she shapes the community through resources and surveillance, never fully committing yet never relinquishing control. These different models of leadership—visionary, passive, financial—interact in dysfunctional ways.

As tensions rise within the sanctuary, there is no clear path for conflict resolution, no sustainable model of governance. The lack of checks and the fragility of ego lead to fragmentation rather than cohesion.

Even among members who seek guidance, such as Sojourner or Bounce, there is no consistent moral or emotional anchor. The novel reveals that visionary leadership, when not accompanied by adaptability and empathy, can become tyrannical or hollow.

The community’s descent into ideological confusion is not due to bad intentions but to the inability of its leaders to manage complexity, dissent, and doubt with humility.

The Persistence of Personal Baggage in Collective Spaces

The New Naturals sanctuary is envisioned as a blank slate—a space where members can start over, freed from the constraints and cruelties of the world above. Yet the personal traumas, habits, and histories each individual brings with them do not dissolve upon entry.

Instead, they seep into the community’s foundation, shaping interactions, relationships, and conflicts in ways that the founders did not anticipate. Sojourner’s burnout and psychological instability, Bounce’s volatility, Elting’s unresolved guilt, Buchanan’s cynicism, and Gibraltar’s quiet despair all manifest within the sanctuary, often disrupting the idealistic narrative being constructed.

The characters are not transformed by the space; rather, the space is contorted by their unresolved baggage. Conversations become battlegrounds, relationships tilt toward dysfunction, and trust fractures easily.

Even as they attempt to craft a new society, they carry forward the very emotional legacies that fragmented the old one. The novel suggests that any collective project which does not actively create space for emotional reckoning is doomed to absorb and reproduce the traumas it aims to heal.

Therapy is replaced by ideology, and introspection by architecture. This creates a disconnect between aspiration and reality that haunts the community from within.

The mountain, while physically sealed, is emotionally porous—filled with ghosts of the past that no wall can keep out. The theme underlines that healing is not communal by default; it must be deliberate, painful, and personal.

Without such work, collective dreams become weighted by individual damage, collapsing under their own unmet emotional needs.