The Night Parade Summary and Analysis

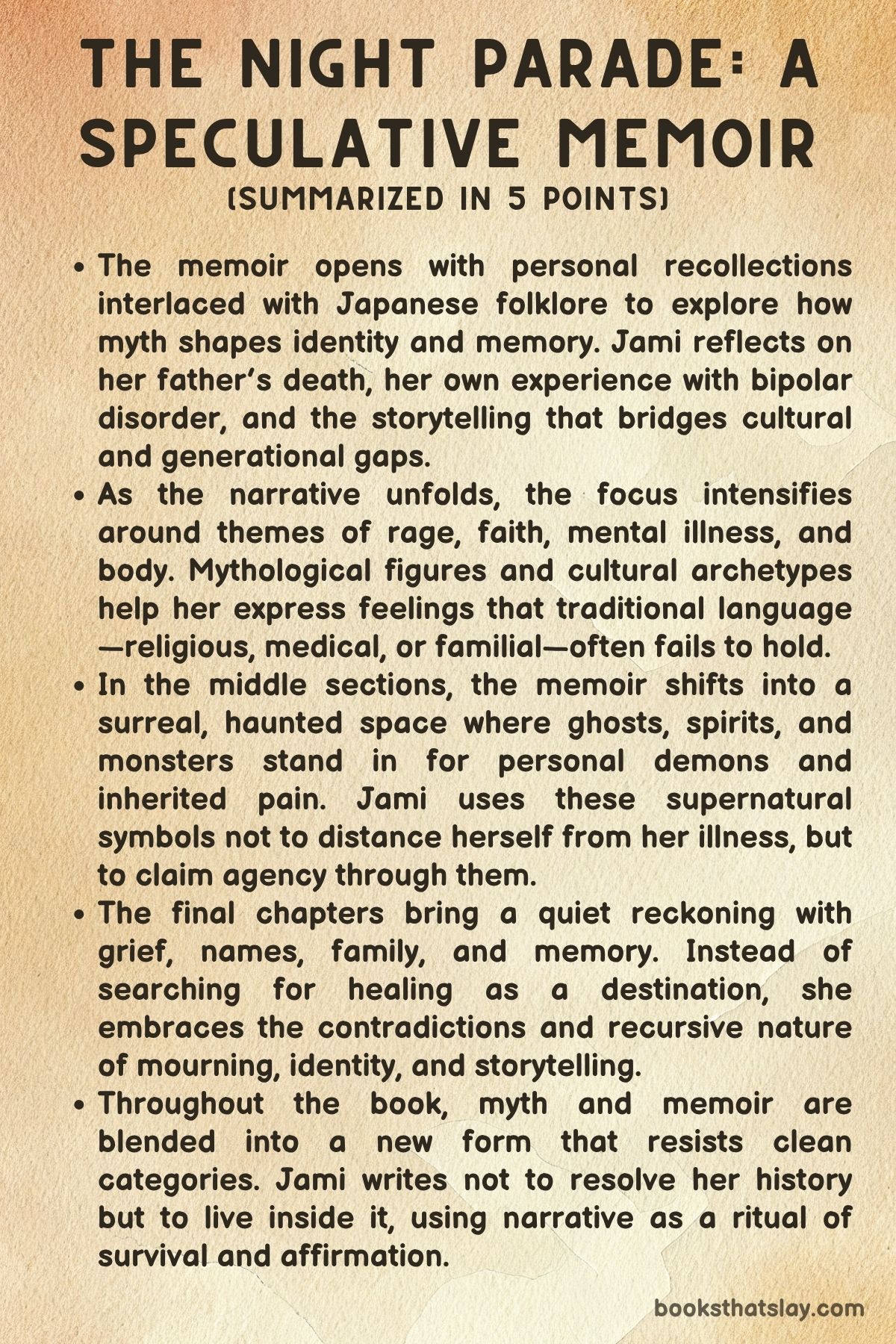

The Night Parade by Jami Nakamura Lin is a genre-bending memoir that merges personal experience with Japanese folklore, speculative fiction, and cultural critique. It examines the intersections of mental illness, intergenerational trauma, diasporic identity, grief, and myth.

The book’s structure follows the Japanese kishōtenketsu form, where narrative progression relies not on conflict but on development and transformation through juxtaposition and resonance. Lin writes from a place of emotional honesty and creative experimentation, blending the surreal and the intimate, the scholarly and the mystical.

Her story resists neat resolution, instead affirming fractured memory and nonlinear healing as valid forms of truth.

Summary

Jami Nakamura Lin begins her memoir with an invocation of myth and memory. In the opening chapters, she evokes the Japanese legend of Urashima Tarō and parallels it with the memory of her father, a Taiwanese immigrant whose love of fishing becomes symbolic of both connection and loss.

Her father’s death leaves a void, and Lin tries to understand the collapse of time that grief and mental illness create. She recounts a stormy fishing trip where she and her father nearly drowned, establishing an early image of chaos, mortality, and the unreliability of memory.

The narrative uses yōkai—folkloric spirits—to represent the fragments of self that become unmoored in the face of trauma. Lin introduces the concept of “automythology,” blending her personal story with cultural myth to emphasize how identities are constructed through storytelling.

During a trip to Tōno, Japan, a place steeped in legends of yōkai, she reflects on her bipolar disorder and the obsessive journaling that defined her adolescence. Rather than offering clarity, these journals reveal the unreliability of personal archives.

The process of myth-making becomes a way for Lin to trace her lineage, manage her illness, and confront her fragmented reality. As the memoir develops, Lin explores rage—not only as a symptom of her diagnosis but as something inherited, racialized, and gendered.

She reflects on her father’s anger, her mother’s stoicism, and her own emotional volatility. These are not isolated traits but part of a lineage shaped by migration, silence, and unspoken grief.

Lin invokes mythical volcanoes and shapeshifters to suggest that rage is ancestral and eruptive rather than pathological. Her religious upbringing also plays a significant role.

Having grown up Catholic, Lin wrestles with how faith interpreted her symptoms as spiritual failure or demonic possession. She reflects on biblical stories, Flannery O’Connor’s writing, and Japanese oni lore to question how sacredness and monstrosity are culturally defined.

Mental illness is often seen as transgression, and Lin’s rejection of those definitions is part of reclaiming her own narrative. Depression is described through the metaphor of the sea—liminal, isolating, and boundless.

She recalls episodes of dissociation and emotional numbness that render her unreachable. Mythical water spirits like umibōzu and nure-onna become emblems of this emotional drift.

The ocean serves as both a site of danger and strange comfort, mirroring her inner state. Later chapters revisit her psychiatric hospitalizations, reframing them through the folklore of fox possession (kitsune-tsuki).

These tales of spirits inhabiting the bodies of women offer cultural parallels to the loss of agency Lin felt under medical care. Rather than resisting the concept of possession, she claims it as a metaphor for the intrusive voices and prescriptive labels she has endured.

Desire and embodiment emerge as central themes when Lin examines her experiences of racism, exoticization, and disassociation from her own body. The image of faceless ghosts (noppera-bō) captures the eerie invisibility she has felt as a mixed-race woman in the U.S.

Her skin becomes not just a boundary but a contested and reclaimed space. The memoir’s pivotal section uses the myth of the Hyakki Yagyō—the Night Parade of One Hundred Demons—as a metaphor for her psyche.

She envisions herself joining this procession of spirits, not as a victim but as a participant in her own haunted interior world. This act symbolizes a radical self-acceptance: embracing the multiplicity of her identity, illness, and past.

In its final chapters, the memoir turns quiet and contemplative. Lin reflects on mourning, not as a finite period but as an altered mode of existence.

Naming becomes a form of agency—honoring ancestors, reclaiming erasure, and preserving lineage. The pandemic becomes another layer of dislocation and survival, with the Year of the Rat symbolizing both endurance and trickery.

Depression reemerges like a whirlpool, cyclical and unrelenting, but no longer entirely feared. The concept of automythology returns—not to explain or cure—but to affirm storytelling as sacred and sustaining.

In the final chapter, drawing from a Taoist legend of the “Three Corpses” who report sins from within the body, Lin offers a vision of coexistence with shame, guilt, and sorrow. She chooses to listen rather than silence them, ending not with resolution but with the dignity of continued survival.

Key People

Jami Nakamura Lin (The Narrator and Central Self)

Jami is both the memoirist and the myth-maker of this speculative narrative. Her character emerges as a deeply fractured yet defiantly self-aware consciousness.

From the earliest sections, she reveals herself as someone who processes trauma, mental illness, and identity through narrative alchemy. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder, Jami does not present herself as a passive subject of psychiatric definition; rather, she is a restless seeker of meaning, translating her internal chaos into mythic language.

She inhabits the margins of multiple identities—racially (Japanese, Okinawan, Taiwanese, American), spiritually (formerly Catholic, now a mythic animist), and mentally (navigating both clinical frameworks and folklore). Each chapter builds a kaleidoscopic portrait of Jami: a daughter mourning her father, a mother confronting generational inheritance, and a writer unmoored by the unreliability of memory.

As the book progresses, she becomes less interested in coherence and more committed to multiplicity. She ultimately embraces her fragmented self as sacred, recognizing that her identity lies not in resolution but in ritual, myth, and return.

Jami’s Father

Though never named directly, Jami’s father is a steady gravitational force across the memoir, even in death. A Taiwanese immigrant and avid fisherman, he is most vividly rendered in the opening chapter “The Dragon King,” where the memory of a near-death fishing trip becomes symbolic of their complex bond.

The father represents calm and routine but is also shrouded in silence and emotional restraint. His presence is mediated through folklore—Urashima Tarō, ocean kings, and posthumous rituals.

After his death, he returns as a ghostly influence in Jami’s dreams and nocturnal rituals, especially during the “Hour of the Ox.” His character oscillates between human memory and divine metaphor, making him less a static portrait of a man than a living mythology within Jami’s emotional and ancestral architecture.

Jami’s Mother

Jami’s mother, in contrast to her father’s spectral peace, often embodies constraint and inherited silence. Her presence is tied to generational trauma, Catholic religious doctrine, and the unspoken transmission of rage.

She is rendered as both a caretaker and a cultural enforcer, shaping Jami’s early moral and gender frameworks while also passing down the burdens of migration, womanhood, and emotional repression. In stories that explore gender and spiritual contradiction, such as “The Temple of the Holy Ghost” and “Possession,” the mother becomes a figure of both authority and complicity.

Jami’s eventual rejection of organized religion is partially a rejection of her mother’s paradigm—but it’s never a wholesale dismissal. The mother, like other figures in the book, becomes a symbol of contradiction: devout yet wounded, loving yet unknowable.

The Daughter (Jami’s Child)

Appearing more prominently in the later chapters, Jami’s daughter becomes a touchstone for legacy, continuity, and re-naming. Through her, Jami confronts the inheritance of trauma and the hopeful possibility of rupture from the past.

The daughter is unnamed in the summaries but is symbolically significant. In “The Naming,” Jami reflects on how naming her child is an act of reclaiming both family lineage and cultural agency.

The daughter does not yet bear the weight of ghosts, yet she stands at the edge of a haunted legacy. She represents potential: to be remembered differently, to embody multiplicity without erasure.

Mythological Avatars and Folkloric Echoes

Integral to this memoir are the yōkai, spirits, gods, and mythical beings that do not just accompany Jami’s story but inhabit it as characters in their own right. These include:

Urashima Tarō, a mythic fisherman who visits the Dragon King’s palace and returns to a world that has aged without him. He mirrors Jami’s fear of psychological dislocation and narrative disjunction.

Kappa, Oni, Kitsune, Noppera-bō, Nure-onna—these creatures reflect Jami’s emotional states: shapeshifting, rageful, erased, seductive, spectral. Rather than being metaphorical accessories, they serve as animate companions in her psychic journey.

The Hyakki Yagyō (Night Parade of One Hundred Demons) becomes a procession of past selves and unintegrated experiences. Jami chooses not to resist these internal specters but to walk beside them, a powerful act of solidarity with her own multiplicity.

In the final chapter, the Taoist legend of the Three Corpses introduces parasites who report sins to heaven. Jami reinterprets them as personifications of shame, guilt, and fear—inner critics she chooses to listen to, rather than purge.

These folkloric characters act as both reflections and distortions of Jami’s selfhood. They are not decorations of the narrative; they are its architecture, embodying trauma, insight, and transformation.

Analysis of Themes

Mental Illness as Identity and Inheritance

One of the central themes of The Night Parade is the experience of mental illness not as an isolated medical condition but as a fundamental part of the self, shaped by heritage, memory, and cultural context. Jami Nakamura Lin presents bipolar disorder not merely as a diagnosis but as a lens through which she experiences the world.

Her mental health struggles are embedded in familial lineage—her father’s death, her mother’s silences, and her own manic-depressive cycles all echo across generations. She explores how psychiatric conditions become embedded in family narratives, altered by immigration, cultural expectations, and systemic erasure.

This inheritance is not limited to genetics but includes unspoken grief, suppressed rage, and fragmented memories that accumulate and manifest as emotional volatility. Lin challenges the pathologizing lens of Western psychiatry by reinterpreting illness through mythology and folklore, especially the yōkai, spirits that are often contradictory, mischievous, or sorrowful.

Rather than seeking to be cured or fixed, she pursues a form of understanding rooted in acceptance and coexistence. Her storytelling resists tidy arcs of recovery, instead illuminating how mental illness, much like folklore, operates in cycles—returning, transforming, and revealing different facets of the self over time.

In rejecting the dominant narrative of mental illness as deviance or disorder, she embraces it as part of a larger story—one shaped by history, myth, gender, and racial identity. Her bipolarity is neither purely medical nor purely metaphorical; it is real and mythic, inherited and embodied.

Mythology as Framework for Truth

Jami Nakamura Lin uses mythology not to escape reality but to reframe it. Myths, legends, and folktales—particularly from Japanese and East Asian traditions—become tools to articulate emotional truths that conventional language fails to capture.

Rather than treating myth as decorative or fantastical, Lin treats it as epistemology: a way of knowing, understanding, and surviving. Her narrative structure borrows from kishōtenketsu, which avoids conflict-driven resolution, instead privileging shifts in perspective and thematic development.

This structure mirrors her own approach to memoir, where contradiction is not resolved but embraced. Lin’s use of automythology—a blending of autobiography and myth—allows her to speak to experiences that defy linear narration, such as trauma, grief, and mania.

Stories like Urashima Tarō, the Hyakki Yagyō, and yōkai lore are not distant cultural artifacts but living frameworks through which she negotiates identity. Myth becomes a form of memory, and memory becomes mythic, especially when the past is fractured or inaccessible.

Rather than asking whether a story is factually true, Lin asks whether it is emotionally and symbolically resonant. She interrogates the boundaries between personal experience and cultural inheritance, showing how stories are always shaped by who tells them, when, and why.

Through this lens, even madness is not chaos but narrative—recurring motifs, voices, and patterns that resist erasure. Myth grants her both distance and intimacy: she can name her pain without exposing it fully, and she can transform suffering into ritual.

This approach affirms that truth is not always found in clarity or coherence, but in resonance and repetition.

Intergenerational Trauma and Silence

The memoir is haunted by silence—the silence of ancestors who did not speak, of parents who could not explain, and of institutions that erased or misnamed. Jami Nakamura Lin portrays trauma as something passed not only through dramatic events but through absence, distortion, and refusal.

Her family’s migration history from Okinawa, Japan, and Taiwan to the United States is marked by rupture and survival, but also by a reluctance or inability to speak openly about suffering. This silence becomes a burden, one she attempts to break through writing.

Her father’s death is a central site of mourning and reflection, but it also represents a larger generational wound—one that is cultural, historical, and personal. Lin grapples with how silence can both protect and harm, and how the stories we inherit often come in fragments, myths, and contradictions.

She attempts to reconstruct what was never fully passed down, recognizing that some of what is lost can only be reimagined. Intergenerational trauma in her narrative is not always violent or explicit; it is embedded in habits, in inherited emotions like rage and shame, and in the dissonance between names and identities.

The pain of being misunderstood—by parents, by institutions, by society—echoes through her exploration of mental illness, racial identity, and gender. Yet rather than viewing this inheritance as entirely destructive, Lin sees it as material for transformation.

By confronting the silence, by giving shape to what was formless, she creates space for complexity and connection. She honors her lineage not by idealizing it, but by making its fractures visible.

Diasporic and Racial Identity

The experience of being a mixed-race Asian American woman is central to Lin’s memoir, not as a peripheral identity marker but as a constitutive force. Her narrative confronts the complexities of diaspora—feeling both too much and not enough, never fully legible in any one cultural context.

She writes about being racialized in America, of being made invisible or exoticized, and how these perceptions shape her understanding of self. Her body becomes a site of projection and contradiction: desired, misread, erased.

These experiences are further complicated by mental illness, which often renders her doubly unintelligible—to others and to herself. Folklore helps her resist the flattening gaze of racial stereotyping.

Through stories of shapeshifters, ghosts, and spirits, she finds metaphors for her own multiplicity. The noppera-bō (faceless ghost) becomes an image for being looked at but not seen, while kitsune (fox spirits) offer models of ambivalence and trickery that resonate with her experience of being misrecognized.

Naming becomes especially significant as she explores the weight of inherited names, the loss of original ones, and the act of naming her daughter as a gesture of agency. Lin does not seek to resolve the contradictions of her identity but instead inhabits them fully.

Her biracial, bicultural background is not something to be reconciled but something to be narrated again and again, from different angles. In this way, the memoir is a form of resistance against assimilationist pressures.

It insists that diasporic identity is complex, unstable, and profoundly shaped by both historical forces and personal mythologies.

Grief as Temporal Disruption

Grief is not portrayed as a single event but as an ongoing disruption to time, self, and story. The death of Jami Nakamura Lin’s father permeates the memoir—not just as a loss but as a temporal rupture that reorders the rest of her life.

She describes mourning not as something that ends, but as a calendar of its own: time measured in memories, rituals, and absences. The past does not stay in the past; it invades dreams, emerges in rituals, and takes the form of ghosts both literal and figurative.

Lin resists narratives that suggest closure or healing as a final stage. Instead, she explores how grief coexists with joy, madness, and daily life. Nighttime becomes a powerful metaphor in this regard—the Hour of the Ox, twilight, and whirlpools all symbolize the times when the boundaries between the living and the dead blur.

In these moments, she feels closest to her father and to the parts of herself that are otherwise unreachable. Rituals—writing, remembering, naming—become ways to survive the unbearable weight of loss.

Even the act of storytelling becomes an offering, a kind of altar. Rather than trying to move on, she writes toward her father, around him, through him. This allows for a more expansive understanding of mourning, one that includes recursion, haunting, and contradiction.

Grief, like myth and madness, becomes something to live with rather than overcome. It is both a wound and a witness, a mark of love that insists on remembrance rather than resolution.