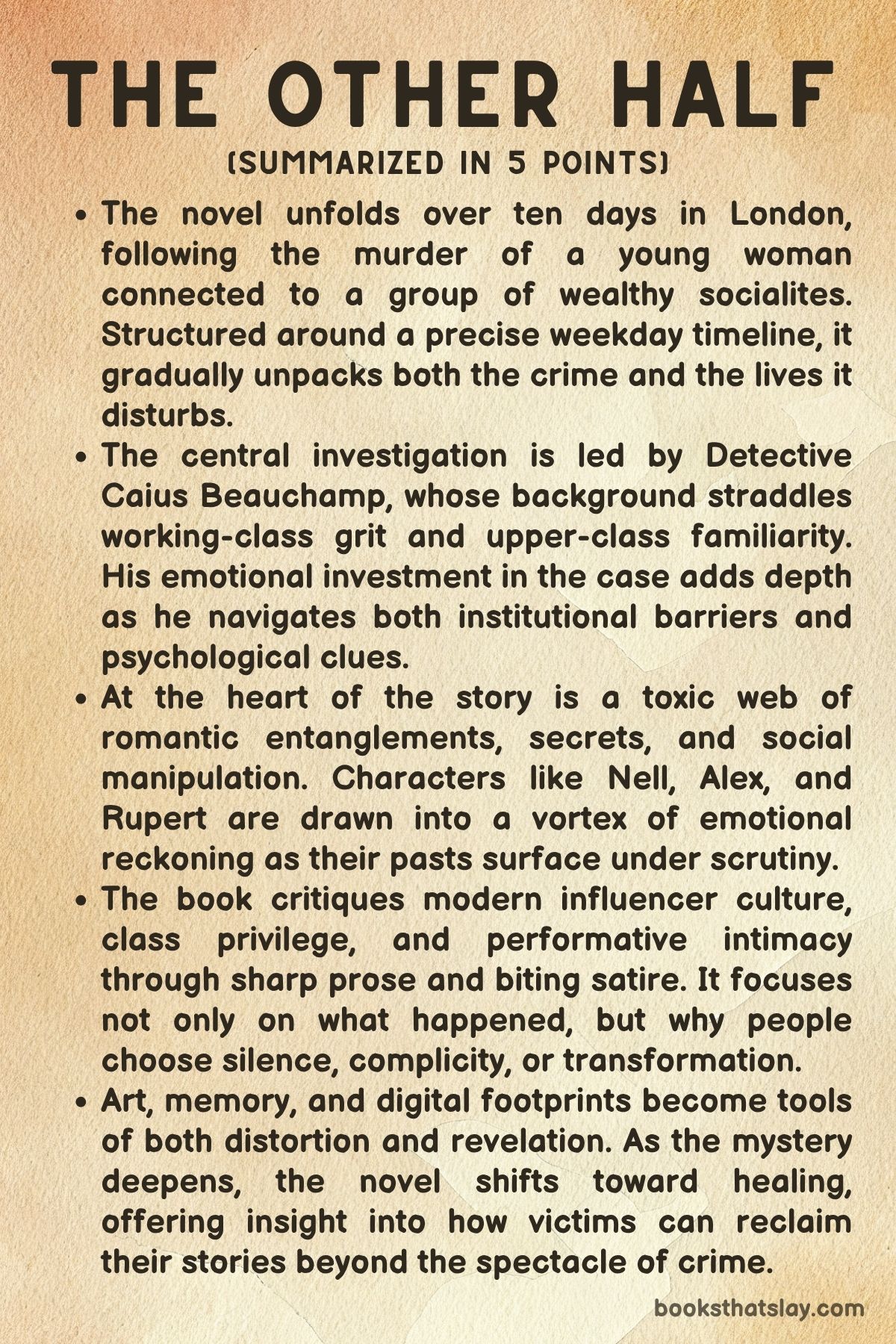

The Other Half Summary, Characters and Themes

The Other Half by Charlotte Vassell is a sharp, contemporary murder mystery set within the glittering but grotesque world of London’s elite. Through the eyes of detectives and former lovers, it explores the aftermath of the death of an Instagram influencer, exposing the toxic undercurrents of privilege, performative beauty, and emotional manipulation.

With a structure that spans eleven days, the novel unfolds in a timeline that mirrors the chaos and unraveling truths of both a murder investigation and the complex psychological relationships surrounding it. It’s a hybrid of procedural tension, social commentary, and intimate emotional reckoning—sardonic, painful, and deeply human.

Summary

The story begins on a summer Saturday night in London, with a haunting depiction of a young woman dying alone in the woods. Her last moments are framed by shame, beauty, and abandonment.

That same evening, Rupert Beauchamp, a privileged aristocrat, hosts a lavish and absurd black-tie birthday party inside a rented McDonald’s in Kentish Town. Among the guests are his ex-girlfriend Nell and her close friend Alex.

Their attendance is emotionally complicated. Nell harbors a mix of resentment and nostalgia for Rupert, while Alex quietly longs for Nell.

The event is a surreal spectacle of wealth, excess, and emotional dysfunction. By Sunday morning, a woman’s body is discovered in Hampstead Heath, disturbingly posed and dressed in red.

The case is handed to Detective Caius Beauchamp and his team, Matt and Amy. They begin to piece together the identity of the victim, later confirmed to be Clemency O’Hara—a wellness influencer, gallery assistant, and Rupert’s girlfriend.

Her social media persona, carefully curated, stands in stark contrast to the vulnerability hinted at in her final moments. The investigation brings to light Clemency’s connections to Rupert’s circle, her increasing paranoia before her death, and the presence of drugs in her system.

Throughout Monday and Tuesday, the detectives collect DNA, scrutinize alibis, and unearth an unsent message from Clemency that suggests she feared for her safety. Rupert’s behavior during questioning is manipulative and dismissive, revealing a pattern of gaslighting and control.

Nell attends therapy and begins to confront her own past with Rupert—especially an incident from a holiday in Greece that left lasting scars. She slowly begins to recognize the emotional abuse she endured, and how it paralleled what Clemency went through.

As Wednesday and Thursday progress, digital forensics reveal deleted messages from Clemency’s phone and GPS data that contradict Rupert’s statements. Clemency’s planner contains notes hinting at a plan to leave Rupert.

Nell revisits her memories and ultimately confronts Rupert, refusing to be silenced. A key piece of evidence—a voice memo Clemency recorded the night she died—surfaces, capturing her fear and indirectly implicating Rupert.

The detectives finalize their timeline, and a warrant for Rupert’s arrest is issued. On Friday, Rupert is arrested in a media spectacle that dismantles his public image.

Nell speaks at Clemency’s memorial, delivering a heartfelt tribute that acknowledges guilt, silence, and complicity. Social media erupts with both grief and activism, transforming Clemency from a digital persona into a symbol of emotional abuse and silencing.

Rupert is formally charged, and his team begins mounting a fragile legal defense. The following Saturday focuses on emotional repair.

Nell visits her childhood home, speaks with Clemency’s mother, and begins forming connections with others who suffered under Rupert’s manipulation. She reflects on her complex friendship with Clemency and burns one of her old sketchbooks as a private ritual.

Caius, shaken by the case, visits his mother and grapples with his own trauma. Rupert is denied bail, and the public turns decisively against him.

On Sunday, Nell spearheads plans for an art exhibition using Clemency’s sketches, zines, and personal work. This becomes a way to reclaim Clemency’s identity—not as a victim, but as an artist with something to say.

She also begins documenting testimonies from other women affected by Rupert. The novel concludes on Monday with the opening of the exhibition.

Nell publishes an essay about coercive control and speaks at a panel discussion. Clemency’s story inspires wider societal dialogue.

Caius steps away from the case, emotionally depleted. Finally, on the second Wednesday, Nell visits the spot where Clemency died.

She leaves a copy of the reprinted zine at the foot of the tree—no tears, no fanfare, just presence. She walks away whole, if not healed.

The cycle ends not with justice in the traditional sense, but with voice, memory, and quiet strength reclaimed.

Characters

Nell

Nell emerges as the emotional and psychological anchor of the novel. Initially introduced as Rupert’s ex-girlfriend, she is immediately set apart by her ambivalence toward the elite social circle she once belonged to.

Her relationship with Rupert is layered with past trauma, control, and emotional manipulation—a pattern she does not fully understand until much later. Her dynamic with Alex is tender but complicated by unresolved feelings and guilt over Clemency’s death.

Nell’s journey is largely internal. She begins in a state of numbness and guilt, suppressing her memories and instincts, and gradually transforms into a woman who reclaims agency and truth.

Her therapy sessions act as a mirror for the reader, slowly unraveling the emotional abuse she endured. By the novel’s end, Nell evolves from passive observer to active advocate—curating Clemency’s posthumous art show, publishing a revealing essay, and forging solidarity with other victims.

Her final act—placing Clemency’s zine under the tree—symbolizes not just closure, but a redefinition of identity rooted in truth and resistance.

Rupert Beauchamp

Rupert is the embodiment of privilege weaponized. A manipulative aristocrat whose charm masks deep cruelty, he thrives on power, secrecy, and emotional control.

Initially charismatic and enigmatic, he gradually reveals himself as a narcissist who uses his social standing to dodge accountability. His relationships—with Clemency, Nell, and his social circle—are transactional and performative.

He gaslights, isolates, and objectifies women, using culture, wealth, and even art as tools of domination. Rupert’s narrative arc is one of collapse.

As the investigation unfolds, his polished veneer cracks under the pressure of contradictory testimonies, digital evidence, and shifting social tides. His emotional detachment, class arrogance, and controlling behavior are systematically exposed.

He attempts to maintain control until the very end, but each lie and manipulation pushes him further into isolation. His arrest is not only a legal consequence but a symbolic disempowerment.

Rupert ultimately serves as a critique of systemic impunity—of how charm, class, and male entitlement are used to silence and erase.

Clemency O’Hara

Clemency, though murdered early in the novel, becomes its most haunting presence. An influencer, artist, and romantic partner of Rupert, she straddled the line between curated perfection and private despair.

Through flashbacks, social media reconstructions, and recovered messages, we see a woman suffocated by the roles she was forced to perform. Her influencer persona was radiant, stylish, and socially connected—but her inner life was filled with fear, doubt, and a desperate desire for freedom.

Her death is both literal and symbolic: the ultimate silencing of a woman whose voice had been undermined for too long. The posthumous recovery of her art, zine, and voice memo becomes the emotional backbone of the novel.

Rather than letting her become a mere victim, the narrative insists on her humanity—her creative impulse, her longing to be seen, and her slow realization of the abuse she endured.

By the novel’s close, Clemency becomes not only a symbol of grief, but of resilience, creativity, and collective memory.

Caius Beauchamp

Caius is the lead detective, driven by an understated moral compass and a growing frustration with the limitations of the justice system. His character functions as both investigator and silent narrator of systemic failure.

Though he shares a surname with Rupert, he is far removed from the elitism that Rupert represents. Caius is emotionally intelligent, haunted by his mother’s own experience with abuse, and often introspective.

His dogged pursuit of truth contrasts with the institutional inertia and media spin that threatens to derail justice. As the case progresses, Caius grapples not only with the murder but with his place within a flawed system.

By the end, emotionally depleted, he steps away from the case, suggesting that personal conscience sometimes exists in tension with bureaucratic roles. His character reinforces the idea that justice is not always found in courtrooms, but in memory, solidarity, and acknowledgment.

Alex

Alex functions as a counterweight to Rupert—gentle, introspective, and emotionally available. His role as Nell’s companion begins with unspoken love and cautious loyalty.

While he harbors romantic feelings for Nell, he never pressures her, instead offering a presence marked by patience and quiet strength. His emotional intelligence is subtle yet profound.

This is especially apparent in contrast to the grandiosity of Rupert and the superficiality of their shared social sphere. As Nell begins to confront her trauma and grief, Alex remains steady but never possessive.

He supports her artistic efforts and represents a future where relationships are not defined by power but by mutual trust. His arc is understated but vital, showing how healing often begins with simple, steadfast companionship.

Amy and Matt

Amy and Matt, detectives working alongside Caius, provide both procedural momentum and emotional depth to the investigation. Amy, in particular, is a standout—methodical, empathetic, and tech-savvy.

Her ability to map digital timelines and track deleted content makes her instrumental in breaking the case. But beyond her technical prowess, she displays emotional insight.

She is especially perceptive when interviewing witnesses and understanding the nuances of psychological abuse. Matt, more grounded and stoic, complements her intellect with streetwise intuition.

Together, they represent the possibility of a new kind of justice work—one that listens, adapts, and learns. Their subplot of training other officers to recognize coercive control and emotional manipulation shows the ripple effect of Clemency’s story beyond the courtroom.

Their work affirms that justice is not just punitive—it is also preventative and educational.

Themes

Coercive Control and Emotional Abuse

One of the most persistent and harrowing themes in The Other Half is the presence of coercive control, especially in romantic relationships. Through the character of Rupert Beauchamp, the novel examines how emotional abuse can thrive behind charming façades and within privileged social circles.

Rupert never physically harms Clemency or Nell in the traditional sense. But his manipulation, gaslighting, and psychological domination leave deep scars.

He exerts control over Clemency’s social presence, isolates her from allies, and rewrites their shared history to maintain his image. The abuse is insidious, making it harder for Clemency and Nell to identify it as such until the damage is irreversible.

Rupert’s behavior exposes the limitations of legal definitions of abuse, as emotional and psychological harm remain difficult to prosecute despite their devastating impact. The book’s structure reinforces this, showing flashbacks of manipulation and the eventual realization and confrontation that Nell undergoes.

Emotional abuse is not only seen in romantic relationships but mirrored in Rupert’s interactions with friends, police, and even the media. He performs control as a default mode of operation.

What emerges is a painful critique of how such abuse often hides in plain sight. It is protected by charisma, wealth, and societal indifference.

Class Privilege and Institutional Failure

The novel draws a stark line between justice and the protective power of class. Rupert’s aristocratic status doesn’t just afford him wealth and comfort—it acts as a shield, a buffer against scrutiny, suspicion, and consequence.

From the moment the investigation begins, he weaponizes his upbringing and elite social ties to distort narratives, frame himself as the victim, and subtly intimidate others. Clemency’s death and the slow crawl toward accountability highlight how the legal system is not built to contend with the social armor of the upper class.

The police investigators, particularly Caius, Amy, and Matt, often hit bureaucratic or legal walls that delay Rupert’s arrest or dilute the severity of his actions. Rupert’s confidence in evading justice stems from his belief that the system will protect him—an assumption that holds true for much of the novel.

Even when Clemency’s voice memo and digital evidence emerge, the legal framing still hinges on subtle interpretations of psychological abuse. These are forms of violence that institutions are ill-equipped to prosecute fully.

This theme critiques the intersection of privilege and legal inertia. It suggests that justice is not just delayed but structurally uneven.

It asks a difficult question: how many abusers go unpunished because they are born into immunity?

Identity, Performance, and the Illusion of the Digital Self

Throughout The Other Half, characters construct identities not based on who they are, but who they want the world to believe they are. This is especially true for Clemency, whose existence as a wellness influencer is built on curation and self-mythologizing.

Her Instagram feed portrays calm, beauty, and confidence, but her private life is defined by fear, instability, and coercion. This tension between image and reality becomes a critical element of the murder investigation, as detectives sift through digital footprints that only partially hint at her suffering.

Even in death, Clemency’s online legacy is subject to distortion. She is commodified by strangers, misread by tabloids, and aestheticized by the public.

The novel critiques how digital spaces enable both self-expression and self-erasure. The performance of perfection demanded by social media not only isolates but also silences.

It makes it harder for women like Clemency to speak out without seeming “hysterical” or “dramatic.” Meanwhile, Rupert and his social circle also engage in performance, using curated parties, PR campaigns, and media manipulation to preserve a polished reputation.

Identity here becomes transactional, shaped by optics rather than truth. The result is devastating: real people become invisible behind the roles they are forced to play.

Grief, Memory, and Reclamation

A quieter but powerful theme emerges in the second half of The Other Half. It focuses on how memory, grief, and storytelling can become acts of resistance.

Clemency’s death becomes not just a personal loss but a political and communal reckoning. Nell, initially passive and guilt-ridden, transforms into a steward of Clemency’s memory.

She does not seek revenge but aims to restore Clem’s humanity by curating her artwork, amplifying her voice, and uncovering the suppressed parts of her identity. This shift in narrative—from crime thriller to emotional archive—is intentional and important.

The book asks what it means to honor someone who was erased in life and immediately objectified in death. Through art, essays, and community dialogue, Clemency is rehumanized—not just remembered, but reframed as an artist, thinker, and woman who existed beyond her trauma.

Memory becomes a living force, shaped not by those who silenced Clemency but by those who truly saw her. The rituals—placing the zine under a tree, burning a hated sketchbook, opening an exhibit—serve as counterweights to the coldness of Rupert’s world.

They reintroduce empathy, nuance, and emotional continuity into a story that was once defined by rupture and cruelty.

Female Solidarity and the Power of Storytelling

In the wake of Clemency’s death, what slowly takes root is a form of resistance grounded in collective truth-telling. Nell, who once ignored warning signs and distanced herself out of fear, begins to connect with other women who suffered at Rupert’s hands.

These connections are not loud or radical in appearance, but their power lies in being heard, believed, and remembered. Through conversations, gatherings, and the publication of Clemency’s zine and Nell’s essay, the novel shows how storytelling can shift power.

It becomes a means of healing and of bearing witness. Importantly, these stories are not just shared for justice—they are shared to reclaim agency.

Clemency, who was once spoken over in life and aestheticized in death, becomes the author of her legacy through others’ willingness to share her truth. The novel critiques how society isolates victims and protects perpetrators by keeping stories in silence or framing them through damaging narratives.

By centering voices previously dismissed, the book argues that real change does not begin with court verdicts or headlines. It begins in the spaces where women speak, listen, and remember together.