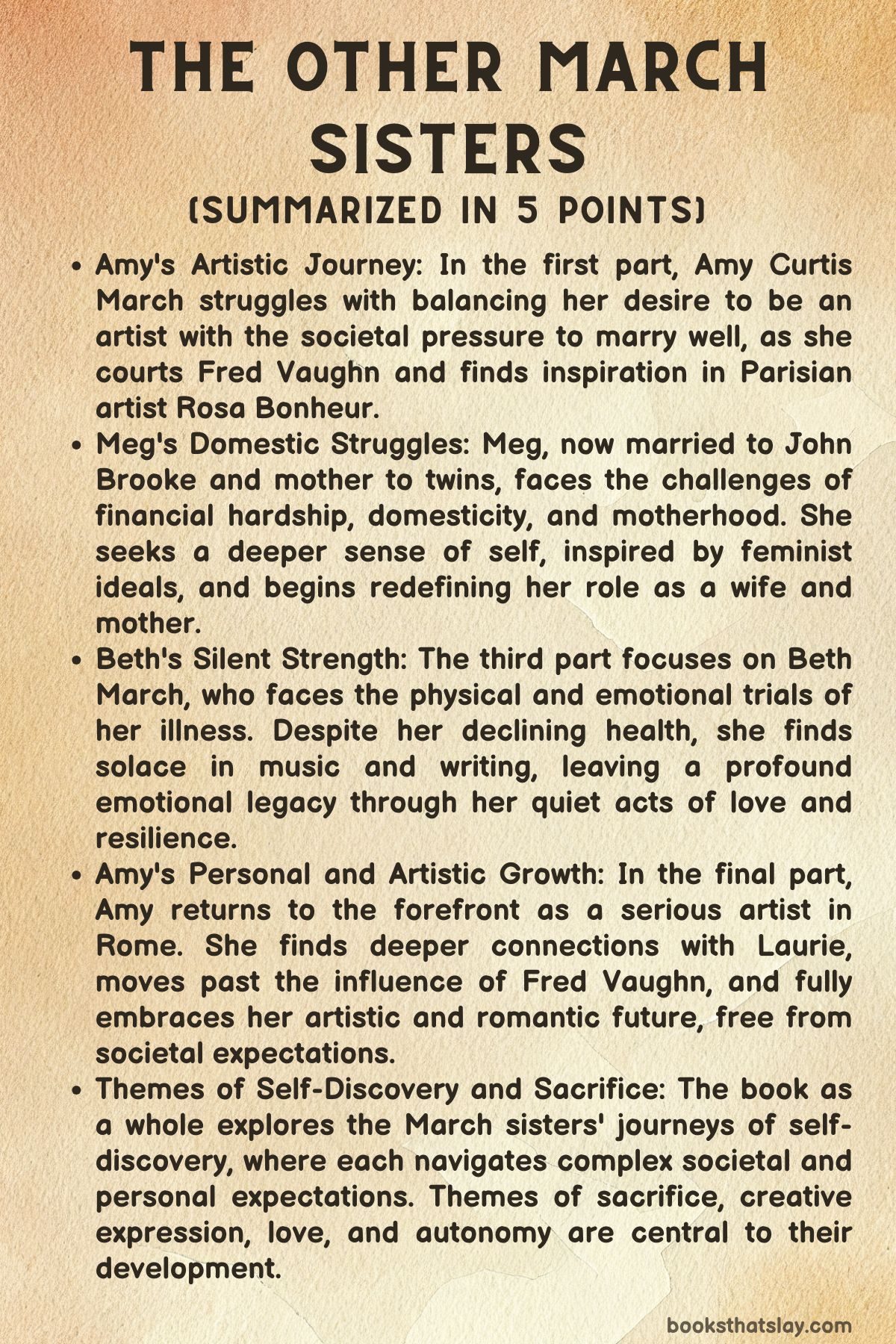

The Other March Sisters Summary, Characters and Themes

The Other March Sisters is a fresh, contemporary take on the classic Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. Written by Linda Epstein, Ally Malinenko, and Liz Parker, this novel shifts the focus from the original March sisters to their modern-day counterparts, exploring their evolving relationships, personal growth, and the timeless struggles of balancing family expectations with individual dreams.

Through a blend of art, romance, and societal pressures, the novel paints a vivid picture of the struggles women face in finding their own path while honoring their past and familial bonds. The story is a rich, thought-provoking exploration of identity, autonomy, and love in the modern world.

Summary

The Other March Sisters reimagines the lives of the beloved March sisters in a contemporary setting, particularly focusing on Amy March’s journey of self-discovery, her artistic aspirations, and her struggles with societal and familial expectations. In the novel, Amy is living in London, seeking to establish herself as an artist while grappling with the pressures of her upper-class background.

Despite her artistic ambitions, she is expected to behave in a manner befitting her social status, and this duality defines her experience.

Amy’s complicated relationship with Fred Vaughn, a suitor chosen by her family, is a major theme. Fred represents a life of stability and convention, an ideal match in many ways.

He is attentive, gentlemanly, and proposes to Amy with the promise of a secure future. However, Amy feels an internal conflict, torn between the life she is expected to lead and her own desires.

As she spends more time with Fred, she feels stifled by his views and by the societal roles that are thrust upon her as a woman. Her yearning for freedom and artistic expression clashes with the confines of her upper-class lifestyle.

Despite Fred’s attentiveness and proposal, Amy cannot deny her growing feelings for Laurie, a childhood friend. Laurie, a complex character who has always shared a deep connection with Amy, further complicates her emotional journey.

Their reunion in Paris marks a turning point for Amy, as Laurie provides a sense of comfort and emotional connection that she has never felt with Fred. The more time Amy spends with Laurie, the more she is able to embrace her true self, unburdened by the weight of societal expectations.

Laurie’s relationship with Amy is not bound by traditional norms. Their bond is rooted in shared artistic passions and a mutual understanding that transcends conventional romantic roles.

This dynamic challenges Amy’s previous notions of love and relationships, prompting her to reevaluate what she truly desires in life.

During her time in Paris, Amy flourishes artistically. She finds solace in her art, using it as a tool for self-expression and a way to reconcile the competing forces in her life.

She begins to see that art is not just a passion, but a defining part of her identity that cannot be ignored. Her artistic mentor, Mary Cassatt, encourages her to make a choice between her passion for art and the conventional life of marriage.

This advice serves as a catalyst for Amy, urging her to confront the limitations placed upon her by society and her family.

Amy’s time in Paris also gives her the space to confront the weight of her emotions and desires. The moment she receives a telegram from Laurie, announcing his arrival in London, marks the culmination of her emotional turmoil.

Laurie’s unannounced visit evokes mixed feelings in Amy—excitement and confusion, and it reignites her internal conflict. Despite her growing affection for Laurie, she remains unsure of how to reconcile her feelings for him with the societal pressures that are bearing down on her.

As Amy struggles with her conflicting emotions and the expectations of her family, she faces a critical decision when Fred proposes to her. His offer symbolizes the safe, traditional life that her family desires for her, but it also represents a future in which her artistic aspirations may be suppressed.

Amy realizes that she cannot marry Fred solely for security, as she would be sacrificing her dreams in the process. This realization forces Amy to confront the painful truth that her family’s expectations are not aligned with her personal aspirations.

After much reflection, Amy makes the difficult decision to decline Fred’s proposal. She chooses to follow her artistic path, one that allows her to live authentically and pursue her dreams without being tethered to societal expectations.

This decision marks a significant turning point in her life, as she comes to terms with the fact that her love for Laurie is rooted in shared artistic ideals and personal freedom, rather than traditional romantic love.

Amy’s emotional clarity and growth come to fruition as she and Laurie explore their relationship further. Laurie’s openness about his attraction to both men and women allows Amy to embrace a more fluid view of love and relationships.

This new understanding strengthens their bond and provides Amy with the reassurance she needs to continue pursuing her dreams. Her decision to live life on her own terms, free from the constraints of family and societal pressure, becomes a powerful statement of self-determination and personal liberation.

In the final stages of the novel, Amy’s transformation is complete. She has learned to live authentically, rejecting the notion of self-sacrifice for the sake of others.

Through her art, her evolving relationship with Laurie, and her decision to follow her own path, Amy finally reconciles her desire for love and artistic fulfillment. The novel ends with Amy embracing her independence, knowing that she has the power to create her own future, one that balances her passion for art with the love she shares with Laurie.

In sum, The Other March Sisters is a powerful exploration of self-identity, artistic ambition, and the struggle between personal desires and societal pressures. Through Amy’s journey, the novel highlights the complexities of love, the challenges of navigating family expectations, and the importance of living authentically.

The story provides a modern perspective on the timeless struggles women face in defining themselves and finding the courage to pursue their dreams on their own terms.

Characters

Amy March

Amy March’s journey is one of self-discovery, conflict, and ultimate resolution as she navigates the complex intersection of family expectations, societal pressures, and her artistic ambitions. From the outset, she is torn between the conventional path her family envisions for her and her desire to become a renowned artist.

Her relationship with Fred Vaughn, a suitor who represents security and tradition, highlights the tension between societal norms and personal desires. Amy finds herself drawn to Fred’s attention, yet she struggles with his somewhat predictable and conservative views on life, which do not align with her progressive aspirations as an artist.

As her time in Europe unfolds, Amy grapples with these competing forces, experiencing the freedom of pursuing her art but also feeling the weight of her family’s expectations. Her internal conflict deepens when she is faced with Laurie, a childhood friend whose emotional support and shared artistic vision awaken feelings in Amy that she cannot ignore.

Though she initially tries to suppress her emotions toward Laurie after an awkward kiss, she cannot deny the depth of her affection for him. Ultimately, Amy’s decision to reject Fred’s proposal reflects her realization that her passion for art and her pursuit of independence are more important than the security of a traditional marriage.

Through this rejection, Amy asserts her right to live authentically, a choice that allows her to reconcile her desires for love and personal growth. Her reunion with Laurie represents the culmination of this self-discovery, as she chooses to embrace a love that supports her creative ambitions, free from the societal constraints that once seemed inescapable.

Meg March

Meg March’s storyline centers on her struggle for independence while navigating the complexities of her family relationships, particularly with her mother, Marmee. Initially, Meg finds fulfillment in her herbal practices and the sense of autonomy it provides.

However, when Marmee arrives for a visit, Meg is forced to confront the tension between her newfound independence and the deep-rooted expectations her mother has for her. Marmee’s judgmental remarks, particularly regarding Meg’s use of herbal remedies during pregnancy, further intensify the conflict.

Meg’s frustration with Marmee’s control over her life comes to a head in a raw confrontation, where she vocalizes her resentment and asserts her right to make her own choices. This moment marks a pivotal point in Meg’s character development, as she begins to reject the mold her mother has tried to impose on her.

Her evolving relationship with her husband, John, also plays a significant role in her journey. Though John initially aligns with Marmee’s views, his eventual acknowledgment of his past mistakes and his support of Meg’s autonomy marks a turning point in their relationship.

By the end of her narrative, Meg has found a balance between asserting her independence and maintaining her familial bonds, setting the stage for her continued growth as an individual.

Beth March

Beth March’s character is defined by her quiet struggle with isolation, illness, and the desire for recognition. Unlike her sisters, Beth feels invisible, both to herself and to those around her, as her illness becomes a defining aspect of her identity.

Her connection with Florida Ronson, a bright and inquisitive young woman, offers Beth a glimpse of a life where she is seen for her talents, not just her role as a sickly family member. Though Beth longs for connection, she is trapped in her own self-doubt and fear of failure.

Despite her overwhelming insecurities, Beth’s decision to teach Florida music signifies a subtle but significant shift in her character. She begins to see herself as more than just an ailing figure in the background, realizing that she has the power to inspire and make a difference.

This small act of teaching represents a step toward reclaiming her sense of self-worth and purpose, even if it is a quiet victory. Beth’s journey is a poignant exploration of the tension between self-imposed limitations and the potential for personal growth, showing that even in the face of illness, there is room for change and self-discovery.

Laurie

Laurie’s role in the narrative is that of a supportive and understanding figure who provides emotional depth to Amy’s journey. Throughout their interactions, Laurie becomes not only a source of comfort and stability for Amy but also a catalyst for her growth.

While initially, their relationship is marked by ambiguity—exemplified by the awkward kiss at the Louvre—Laurie’s presence in Amy’s life allows her to explore her emotions and desires in a way that feels genuine and unrestricted by societal expectations. Unlike Fred, who represents security and conformity, Laurie embodies the possibility of a more fluid, open relationship that is rooted in mutual respect for each other’s ambitions.

His understanding of Amy’s artistic aspirations and his encouragement for her to follow her creative path serve as a powerful counterpoint to the traditional roles imposed by her family. Laurie’s eventual confession of love for Amy is not an imposition but a natural extension of the bond they share.

This emotional honesty helps Amy realize that she can love without compromising her identity, a revelation that plays a crucial role in her decision to reject Fred and live for herself. Laurie’s evolution throughout the story is intertwined with Amy’s, and his unwavering support allows her to embrace a future where love and art can coexist harmoniously.

Themes

Navigating Societal Expectations

Amy March’s journey throughout The Other March Sisters encapsulates the tension between societal expectations and personal desires. From the outset, Amy is caught in the conflict between fulfilling the roles that society and her family expect her to play and following her own artistic ambitions.

The pressure to conform to the ideals of femininity, propriety, and marriage weighs heavily on her decisions. As a young woman in high society, Amy constantly grapples with the idea of presenting herself in a manner deemed acceptable while secretly longing to break free and embrace her passion for art.

This internal struggle is not just about her love for drawing but also the conflicting desires to be seen as both a respectable lady and a talented artist. Throughout the narrative, the expectations of marriage, class, and social appearances continuously challenge Amy, forcing her to confront how much of her identity has been shaped by external forces.

Her journey becomes a quest to find a balance between her love for art and the roles that society expects her to occupy. The recurring theme of societal expectations ultimately underscores Amy’s personal growth, as she learns to prioritize her own ambitions over the conventions imposed upon her.

Conflict Between Artistic Passion and Social Duty

In The Other March Sisters, Amy’s passion for art stands in direct contrast to her societal duties, illustrating the age-old conflict between personal fulfillment and social obligation. As an aspiring artist, Amy seeks creative freedom, yet this ambition clashes with her family’s traditional expectations, especially regarding her role as a potential wife.

The tension between these two aspects of her life is palpable, especially in moments when she must suppress her creative desires to fulfill social obligations. Her decision to forgo unaccompanied sketching in favor of participating in social events is one example of how her passion for art is frequently overshadowed by the demands of proper society.

This conflict intensifies as Amy interacts with potential suitors like Fred Vaughn, who embodies the conventional future Amy is supposed to want. The stifling nature of Fred’s courtship, though flattering, only highlights the limitations of the traditional life she is expected to lead.

It is only through her experiences in Paris, where she finds both personal freedom and artistic inspiration, that Amy begins to realize that her true happiness lies in pursuing art, free from societal constraints. This theme of reconciling artistic passion with social duty is at the heart of Amy’s journey, as she ultimately seeks to live a life that honors both her creative spirit and her personal desires, rather than bowing to the pressures of tradition.

Personal Identity and Self-Discovery

Amy’s evolution throughout the story is a profound exploration of self-discovery. Initially, she is unsure of her desires and is caught between family expectations, the potential for marriage, and her personal dreams.

The arrival of Laurie in her life and their evolving relationship acts as a catalyst for Amy’s introspection, pushing her to confront her true feelings and ambitions. The time Amy spends in Paris, away from the suffocating influence of her family, allows her to step into a more authentic version of herself, one that is aligned with her artistic aspirations and desires.

Her internal conflict between love and career is deeply rooted in the tension between her desire for independence and her fear of abandoning the comforts of a more traditional life. Ultimately, Amy’s journey is marked by the realization that her identity is not defined by the roles others expect her to play but by her own choices.

Through her relationship with Laurie and her devotion to her art, she discovers that she can have both love and artistic fulfillment, but only if she chooses to live on her own terms. This theme of personal identity is crucial, as it underscores the importance of self-acceptance and the courage to embrace one’s true self, even when it means rejecting societal expectations.

Love and Independence

The tension between love and independence plays a pivotal role in The Other March Sisters, particularly in Amy’s evolving relationship with Laurie and her eventual rejection of Fred’s proposal. Amy’s journey is as much about finding her place in the world as it is about understanding what love truly means to her.

While Fred represents stability and societal acceptance, Laurie embodies a more complex and authentic form of love, rooted in mutual understanding and shared passions. Initially, Amy struggles with the idea of choosing between the security that Fred offers and the more uncertain but deeply fulfilling connection she shares with Laurie.

However, as the story progresses, Amy’s personal growth allows her to recognize that love does not have to be defined by the conventional roles she has been taught to aspire to. Her decision to decline Fred’s proposal marks a turning point, as she realizes that independence—both in her career and in her relationships—is essential to her happiness.

Through her connection with Laurie, Amy learns that true love is not about conforming to expectations or seeking approval from others but about forging a relationship that is based on mutual respect, shared values, and emotional freedom. Ultimately, Amy’s journey reflects the balance between the desire for love and the need for independence, showing that the two can coexist when one lives authentically and on their own terms.

The Influence of Family and Tradition

Family plays a central role in shaping the characters’ choices in The Other March Sisters, and the influence of familial expectations is particularly evident in Amy’s internal struggles. From the very beginning, Amy is confronted with the expectations of her family, particularly her mother, who seeks to mold her into the ideal woman—one who adheres to social norms, marries well, and fulfills her duties as a wife and mother.

These expectations are not just about the roles Amy must play but about the values and traditions that have been passed down through generations. While Amy values her family, she also recognizes that these expectations limit her potential and suppress her artistic desires.

Her journey is thus a process of reclaiming her identity and pushing back against the constraints her family has placed on her. The narrative also highlights the tension between honoring tradition and pursuing personal fulfillment, as Amy realizes that she must find a way to honor her family’s values without sacrificing her own dreams.

The theme of family and tradition is explored in Amy’s evolving relationship with her mother, her rejection of Fred’s proposal, and her eventual acceptance of her identity as an artist. Through this theme, the story examines how family dynamics can both nurture and constrain personal growth, and how individuals must navigate the delicate balance between loyalty to their families and the need to forge their own paths.