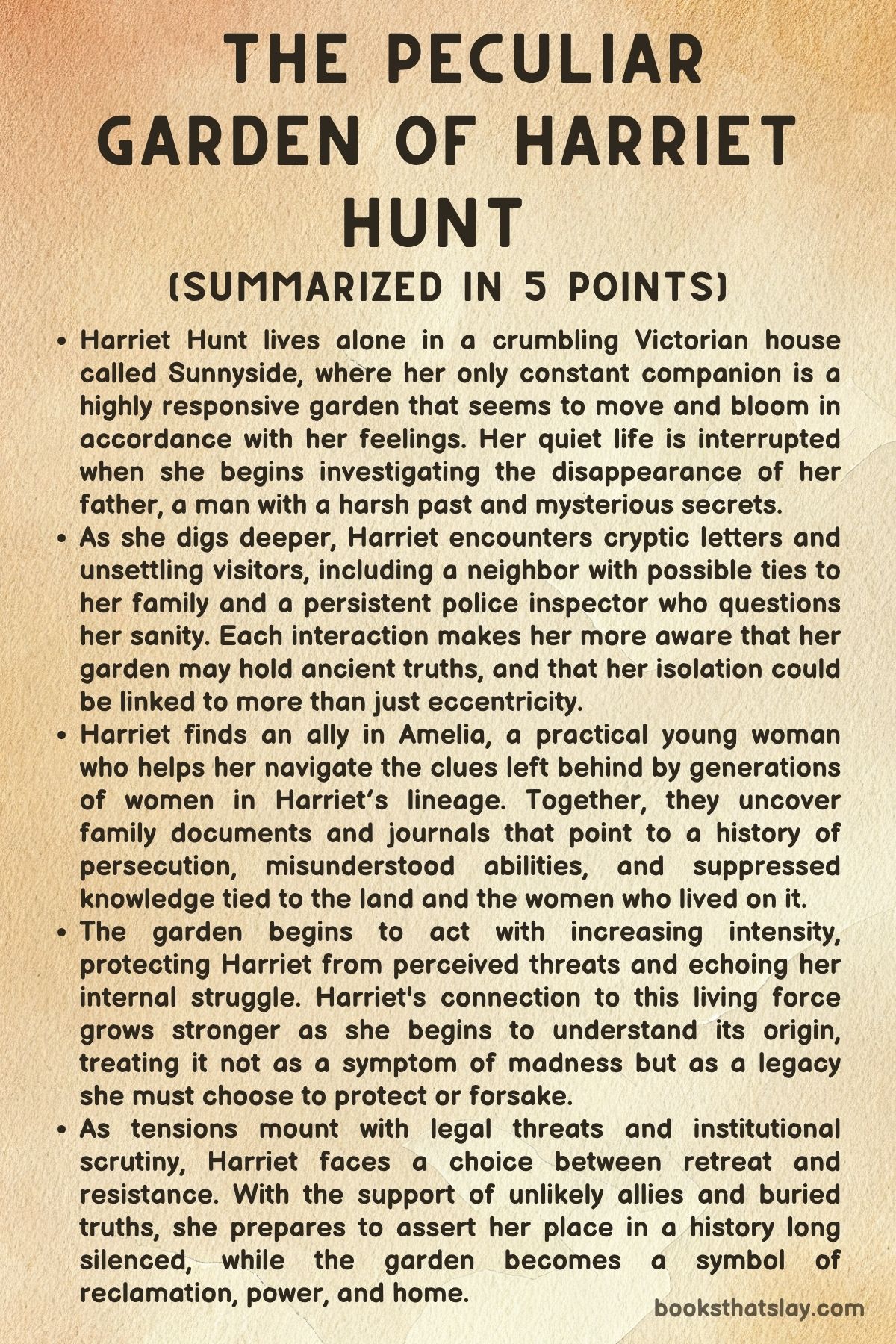

The Peculiar Garden of Harriet Hunt Summary, Characters and Themes

The Peculiar Garden of Harriet Hunt by Chelsea Iversen is a darkly enchanting novel that explores the complex inner world of a woman who lives in isolation with a garden that responds to her emotions. Set in a slowly crumbling estate named Sunnyside, the story blends magical realism with gothic domestic suspense, following Harriet Hunt as she navigates the trauma of her past, an emotionally reactive garden, and growing suspicion from the outside world.

This is a narrative about survival, the fragility of trust, and the unexpected power that comes from embracing one’s true self—even when the world tries to call it madness.

Summary

Harriet Hunt lives alone in Sunnyside, an old estate overshadowed by decay and memories of violence. Her closest companion is her garden—a wild, lush, and seemingly sentient landscape that reacts to her emotional states.

Harriet’s father, a cruel and controlling man, has been missing for over seven months, believed to have fled to Denmark to escape debt. In his absence, Harriet survives quietly, pawning his possessions and keeping to herself.

She avoids opening a letter she receives, signaling her resistance to confrontation and change.

When Inspector Stokes arrives to investigate her father’s disappearance, his probing questions and sharp instincts rattle Harriet, raising the stakes of her quiet, reclusive life. The garden responds protectively to her stress, threatening exposure of its unusual behavior.

Stokes leaves with a warning that he will uncover the truth, triggering Harriet’s fear of being labeled unstable—an echo of her father’s threats to have her institutionalized.

Harriet’s only warmth comes from her cousin Eunice, whose visits provide temporary relief from her solitude. But Eunice announces that she is moving away, and though they part with a promise to write, Harriet is devastated.

Left alone, Harriet begins experiencing disturbing noises and ghostly reflections, which reveal her fraying mental state. When her garden mysteriously returns the unopened letter, she learns it’s from a man named Nigel Davies, who hints at a long-buried family secret.

Though hesitant, Harriet grows curious about the potential for answers and freedom.

As she considers responding, Harriet reminisces about her mother, whose quiet love and secret lessons shaped her early sense of self. A hidden painting and an old note to her deceased mother rekindle Harriet’s sorrow and guilt.

One day, a young postman brings another letter, and a small mishap during the hand-off leads to an unexpected encounter with a man named Christian Comstock. Unlike others, Christian treats Harriet with kindness, and their meeting stirs a cautious interest in connection.

Harriet prepares for a visit from her former housekeeper, Mrs. Botham, who arrives with her daughter, Amelia.

Their reunion is tense, shadowed by Harriet’s memories of being mistreated and confined after her mother’s death. Yet she agrees to hire Amelia in exchange for information.

Mrs. Botham reveals that Harriet’s father may be staying with a cousin in Copenhagen, prompting Harriet to send a letter there.

Amelia proves to be surprisingly capable, and the two women begin forming an uneasy but useful alliance.

Amelia suggests visiting the local pub for information, where they again meet Christian. He volunteers to help and confirms that someone matching her father’s description spoke of a long holiday.

Harriet agrees to walk with Christian and meets his cousins Greenwood and Anna. For the first time, Harriet feels welcomed into a social circle.

She is intrigued by Christian’s apparent sincerity, though still guarded.

However, Harriet’s trust in Christian begins to unravel when her sense of control falters. Christian’s gentle demeanor gives way to manipulation and cruelty.

He lashes out violently, and Harriet realizes he is not a protector but a threat. Despite the danger, she continues investigating her father’s disappearance with Amelia’s help.

Their trip to the docks yields little but reveals Amelia’s illiteracy, prompting Harriet to promise to teach her.

At home, Christian’s behavior grows erratic and sinister. During a Halloween party, he secretly hurts Harriet while appearing affectionate in public.

Harriet retaliates subtly during the party’s murder mystery game, asserting her cunning. But that night, Christian escalates further, allowing Harriet’s dress to catch fire and abandoning her.

Amelia saves her, but Harriet’s pain causes her to push Amelia away.

Harriet tries to mend their relationship by confessing her guilt over her mother’s death, believing she doesn’t deserve happiness. Her growing self-loathing keeps her tethered to her abusive husband and home.

When she finally tries to meet with Nigel Davies for the truth, Christian sabotages her plans and nearly suffocates her in bed. Though he stops short of killing her, the terror leaves a lasting mark.

Eventually, Harriet flees to Greenwood’s home after enduring a violent clash involving Christian and her estranged father. Greenwood and Anna offer her refuge, and Harriet begins to open up.

Her connection to nature deepens, and she becomes aware that her abilities are not a curse but a gift. She later finds sanctuary at Eunice’s home in Durham, where the woods respond to her presence with quiet reverence.

She helps Eunice with gardening and uncovers a letter from her mother confirming her inherited powers and providing Nigel Davies’s name.

Inspector Stokes reappears briefly, but Harriet remains hidden. Her garden flourishes, and she finds companionship in Greenwood.

At Amelia’s wedding, Harriet gives her the deed to Sunnyside and formally says goodbye to her past. She discovers the buried bodies of Christian and her father beneath her plum tree but chooses not to alert authorities.

Instead, she allows the garden to absorb and bury the final remnants of her pain.

In the years that follow, Harriet builds a new life near Eunice. She starts a family, becomes known for her unusual gardening skills, and marries Greenwood.

Christian is declared dead, and the garden, once a chaotic extension of her trauma, becomes a symbol of peace and renewal. Harriet finally claims her life on her own terms—free, loved, and at peace.

Characters

Harriet Hunt

Harriet Hunt is the deeply complex and emotionally scarred protagonist of The Peculiar Garden of Harriet Hunt. Her life is marked by profound isolation, psychological trauma, and an intense bond with a garden that appears to reflect and amplify her emotions.

From the outset, Harriet is portrayed as a reclusive figure, clinging to the decaying remains of her childhood home, Sunnyside, which is both sanctuary and prison. The magical garden surrounding the estate is more than a backdrop; it is a manifestation of Harriet’s psyche—wild, volatile, and brimming with suppressed emotion.

Her relationship with the garden underscores her inner life: it protects her when she is vulnerable, mirrors her fear and hope, and serves as a silent witness to her suffering. Throughout the novel, Harriet grapples with the legacy of an abusive father and the unresolved grief surrounding her mother’s mysterious death.

Her father’s threats of institutionalization and rejection of her magical abilities haunt her long after his disappearance, reinforcing her belief that her powers are dangerous and shameful. Yet, as she confronts outside forces—such as the suspicious Inspector Stokes, the enigmatic Nigel Davies, and her increasingly manipulative husband Christian—Harriet gradually awakens to her own agency.

Her journey is one of reclaiming identity, autonomy, and power. She learns to distinguish real love from coercion, confronts the ghosts of her past, and embraces the magical inheritance that once frightened her.

Ultimately, Harriet’s transformation is emblematic of survival and self-possession; she evolves from a fearful recluse into a woman capable of love, vengeance, and rebirth.

Christian Comstock

Christian Comstock begins as a figure of charm and intrigue, offering Harriet a rare glimpse of kindness and social connection. His early interactions are characterized by gentleness and curiosity, and his apparent respect for Harriet’s boundaries makes him a refreshing presence in her otherwise suspicious and isolating world.

However, as the novel progresses, Christian’s facade begins to crack, revealing a man driven by control, manipulation, and deeply buried rage. His transformation from suitor to abuser is chilling in its graduality.

Christian gaslights Harriet, isolates her, and ultimately becomes physically violent, culminating in a terrifying moment where he allows her to burn rather than help. This act—utterly devoid of empathy—marks him as a truly dangerous figure, one who hides cruelty beneath a veneer of civility.

Christian’s character serves as a dark mirror to Harriet’s father, both men using institutional threats and emotional coercion to dominate Harriet. Yet while her father’s cruelty is overt and authoritarian, Christian’s is insidious and performative.

His blend of charm and menace represents the most dangerous kind of abuser: one who deceives both his victim and their community. His eventual demise, buried beneath Harriet’s magical garden, is symbolic of Harriet’s liberation—not only from Christian himself but from the cycle of abuse he perpetuates.

Amelia Botham

Amelia Botham begins as a practical addition to Harriet’s life—a housemaid offered by her mother, Mrs. Botham, in exchange for information about Harriet’s father.

However, Amelia quickly proves to be far more than hired help. Intelligent, resourceful, and emotionally astute, she becomes one of Harriet’s few true allies.

Her ability to adapt, work with quiet diligence, and provide emotional companionship softens Harriet’s harsh loneliness. Amelia’s charm lies in her openness and surprising depth; she suggests investigative ideas, keeps Harriet grounded, and even saves her life by extinguishing the flames Christian cruelly let burn.

Her illiteracy, discovered later in the narrative, adds further nuance to her character, revealing vulnerability behind her strength. Harriet’s promise to teach her to read becomes a touching gesture of mutual care.

Though their relationship suffers following a moment of trauma and misdirected anger, it is ultimately restored through mutual understanding. Amelia represents the potential for solidarity among women trapped in patriarchal structures and serves as a foil to Harriet’s inward focus, reminding her of the outside world’s complexities and kindnesses.

Greenwood

Greenwood, Christian’s cousin, enters the narrative as a quiet, observant figure who offers Harriet an escape route when her world collapses. While he initially exists in Christian’s periphery, Greenwood gradually becomes a stabilizing presence in Harriet’s life.

Unlike his cousin, Greenwood is marked by gentleness, humility, and consistency. He does not pressure Harriet for explanations or affection, instead offering her space and safety.

His home becomes Harriet’s refuge when she finally flees Christian’s abuse, and it is there, surrounded by kindness and acceptance, that she begins to rebuild. Greenwood’s respect for Harriet’s boundaries and belief in her intrinsic worth distinguish him from the controlling men in her past.

His slow-burning romance with Harriet is not rooted in domination or rescue but in quiet companionship and mutual respect. Ultimately, Greenwood symbolizes a future Harriet never believed possible—one built on trust, emotional safety, and shared healing.

Eunice

Eunice, Harriet’s cousin, is a steady thread of love and familial warmth throughout the novel. Her visits early in the story offer Harriet moments of normalcy, joy, and affirmation.

Unlike most of the other characters in Harriet’s life, Eunice never doubts her, mocks her, or seeks to control her. Her decision to move away leaves Harriet bereft, but Eunice’s later reappearance at a pivotal time rekindles Harriet’s strength.

Her home in Durham becomes Harriet’s second sanctuary, and it is there that Harriet begins to feel truly safe. Eunice, now a mother, extends the unconditional love Harriet lost with her own mother’s death.

Their relationship highlights the importance of female kinship, emotional safety, and continuity. Eunice does not rescue Harriet, but she makes it possible for Harriet to rescue herself.

Inspector Stokes

Inspector Stokes is a looming presence in the narrative, representing the law, suspicion, and the threat of exposure. His investigation into Harriet’s father’s disappearance casts a shadow over her already tenuous emotional world.

Stokes is perceptive and relentless, and his presence forces Harriet to maintain constant vigilance, particularly with regard to the garden’s magical behavior. Although he never becomes overtly villainous, his presence adds a layer of societal scrutiny that heightens Harriet’s sense of danger.

His role is crucial in amplifying the stakes of Harriet’s secrets and symbolizing the external systems—legal, social, patriarchal—that stand ready to punish deviation from the norm.

Themes

Emotional Repression and Psychic Echoes in the Domestic Sphere

Harriet Hunt’s emotional life is inextricably bound to her home and garden, which act as external reflections of her psychological state. The house is decaying, haunted by memory and dread, while the garden flourishes wildly, dangerously, and with a sentience that mirrors her moods.

This interplay between space and psyche becomes a persistent presence in The Peculiar Garden of Harriet Hunt, where trauma does not remain in the past but is continuously expressed by the environment itself. Harriet’s efforts to maintain composure and avoid societal scrutiny become a desperate attempt to repress not just emotion but magic itself, as both have been deemed dangerous by figures of authority—especially her father.

Her repression is not sustainable. The garden bristles, blooms, recoils, and protects with alarming autonomy, suggesting that Harriet’s suppressed emotions will always find a means of expression, whether she wants them to or not.

Even the threat of being institutionalized becomes a kind of psychological imprisonment she struggles to escape, reinforcing how repression becomes both a shield and a cage. As Harriet becomes more entangled in the mystery of her past and more aware of the true nature of her powers, the house and garden shift accordingly, acting as silent witnesses and active participants in her transformation.

Her path to freedom is not one of conventional escape but of mastering the psychic echoes that have shaped her and taking ownership of the emotional force that once threatened to destroy her.

The Legacy of Abuse and Generational Trauma

Harriet’s story is built on the residual, unhealed wounds left by an abusive father and a mother who, though loving, was powerless to fully protect her. The psychological aftermath of this dynamic casts a long shadow over Harriet’s life and decision-making.

The garden becomes a living relic of these relationships—beautiful, powerful, and also unpredictable, much like her own emotional inheritance. The trauma from her father’s manipulation and control continues to influence her behavior, especially her aversion to outsiders, suspicion of kindness, and the tendency to isolate herself.

Her fear of institutions and being labeled mad directly stems from her father’s past threats, and this fear governs her every interaction with figures like Inspector Stokes or Christian. Harriet’s entrapment in a marriage that later becomes abusive shows how cycles repeat when foundational trauma is not confronted.

Yet the story also explores how these patterns can be interrupted. Harriet’s connection to her cousin Eunice, and later to Amelia and Greenwood, offers a model of chosen family and healthy interdependence.

Even more crucial is her eventual discovery that her magical sensitivity is not a curse but a maternal legacy. This revelation reframes her past not as something to flee from but as something to transform.

Rather than being solely a victim of her ancestry, Harriet becomes its interpreter and healer, channeling the destructive aspects of her inheritance into protective and life-affirming power.

Female Autonomy and Resistance to Patriarchal Control

Much of Harriet’s journey is defined by her struggle to assert independence in a world that persistently seeks to contain, exploit, or discredit her. Her magical abilities, emotional intensity, and refusal to conform to social norms place her in constant danger of being labeled mad, dangerous, or unfit.

Both her father and husband attempt to control her through coercion, surveillance, and outright violence. Her father frames her gift as witchcraft, threatening her with confinement, while Christian uses charm, then cruelty, to dominate her physically and emotionally.

In both cases, her resistance is portrayed as a quiet but fierce assertion of selfhood. Refusing to send a letter, tending a garden in secret, or staging a subtle rebellion during a party become acts of radical defiance.

The presence of other women—especially Eunice and Amelia—illustrates alternative models of female support and survival. Amelia’s own story of illiteracy, labor, and eventual marriage parallels Harriet’s path, reinforcing that autonomy does not look the same for every woman but is always shaped by the resources and relationships available.

Harriet’s ultimate decisions—leaving Christian, claiming her powers, giving away her house, starting a new life—are not grand gestures of escape but hard-won acts of agency. In a narrative saturated with attempts to suppress female will, her final emergence as a gardener, wife, and mother on her own terms becomes a quietly revolutionary act.

The Unseen Magic of Connection and Renewal

Despite the heavy shadows cast by abuse and fear, The Peculiar Garden of Harriet Hunt insists on the transformative power of genuine connection. The garden, though unruly and at times menacing, is also an agent of healing and affirmation.

It does not just react to Harriet’s emotions—it supports her, defends her, and grows with her. Its magic is a metaphor for intuition, grief, and recovery, something deeply personal and yet capable of reaching others.

Harriet’s relationships with Greenwood, Anna, and Amelia slowly begin to untangle the knots of her solitude. What begins as cautious outreach—sending a letter, joining a walk—evolves into the foundation of a new life.

Even her reconnection with Eunice, steeped in childhood memory and maternal comfort, becomes a turning point where she begins to trust in others again. Significantly, it is not a man or a romance that saves Harriet, but the constellation of people who see her clearly and offer her space to be whole.

Her gift, once a burden, becomes a blessing that enriches the lives around her. The garden, in its final flourishing state, mirrors this evolution from isolation to communion.

Harriet’s ability to nurture life—human and plant alike—becomes a symbol of her return to herself. She ends not as a broken woman piecing together ruins but as someone who has cultivated a future from the fragments of her past, rooted in love, magic, and community.