The Phoenix Crown Summary, Characters and Themes

The Phoenix Crown is a captivating historical fiction novel co-authored by bestselling writers Kate Quinn and Janie Chang. Set against the backdrop of San Francisco in the early 1900s, the novel weaves together the lives of four resilient women—Gemma, Suling, Reggie, and Alice—whose fates intersect in the shadow of disaster, betrayal, and the quest for freedom.

With the 1906 earthquake as a turning point, the novel spans across continents and time, from San Francisco to Paris, as the women confront secrets, endure personal trials, and ultimately seek justice against a powerful, corrupt figure.

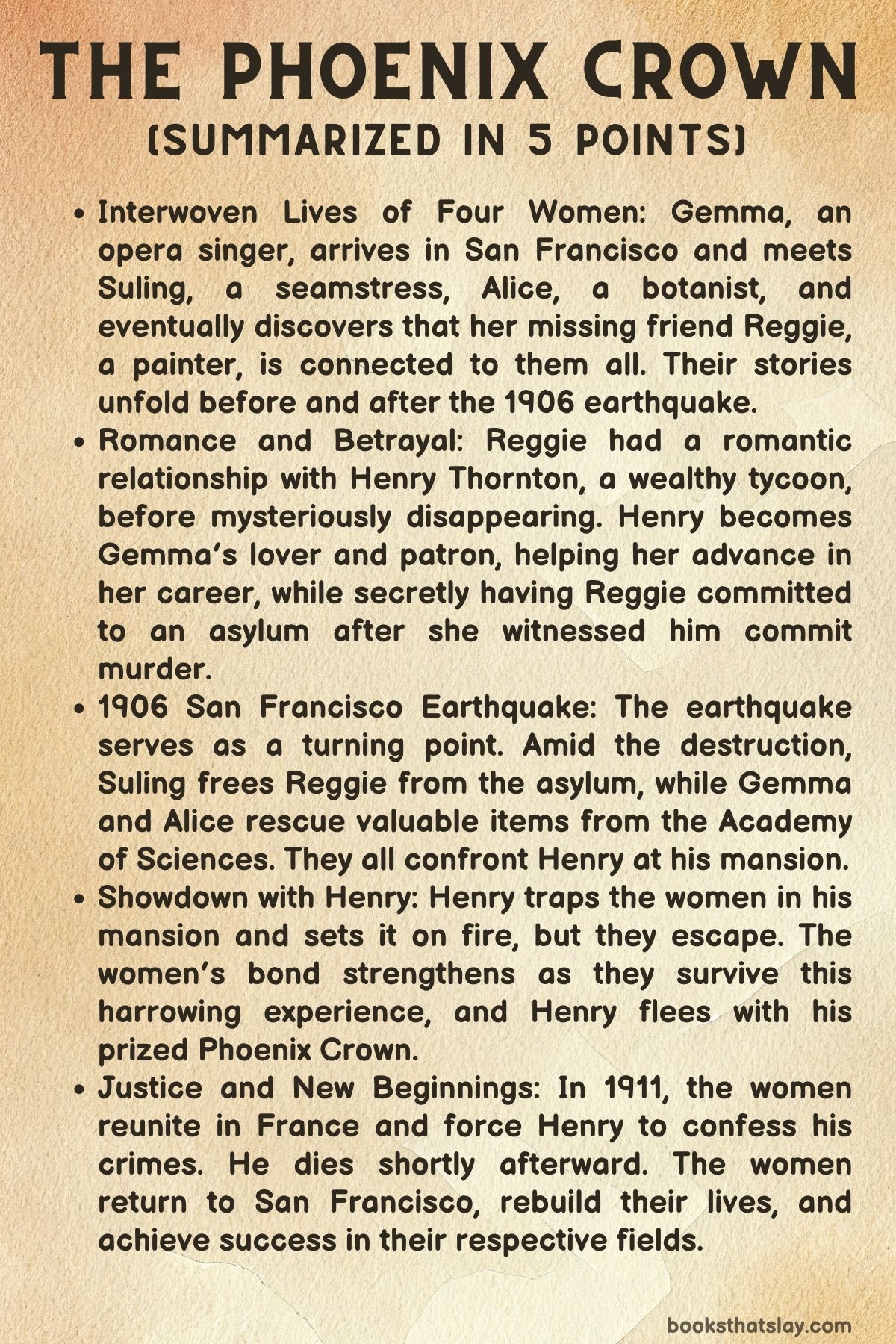

Summary

In San Francisco, 1906, Gemma Garland, a rising opera singer, arrives hoping to rebuild her life after financial ruin. She crosses paths with Suling Feng, a seamstress trying to escape an unwanted marriage, and Alice Eastwood, a botanist, as they each navigate the city’s social fabric.

At the heart of their connections is Reggie, once a painter and Gemma’s close friend, now mysteriously missing. Before Gemma’s arrival, Reggie had been romantically involved with Henry Thornton, a wealthy tycoon. Reggie and Suling fell in love after meeting at one of Henry’s opulent parties, but Reggie soon vanished without explanation.

As Gemma settles into her new life, she encounters Henry, who becomes her patron and later her lover. He offers her a chance to shine in Carmen, securing her a coveted role and introducing her to the city’s elite.

Meanwhile, Suling is trying to avoid an arranged marriage while taking on work at Henry’s mansion, where she crosses paths with Gemma once again.

As they unravel the mystery of Reggie’s disappearance, it becomes clear that Henry has been hiding dark secrets. Suling discovers that Henry had Reggie committed to an asylum, silencing her after she witnessed him commit murder.

On the night of Gemma’s Carmen debut, an earthquake devastates the city, turning their world upside down.

Amid the chaos, Suling rushes to free Reggie from the asylum, while Gemma and Alice help salvage scientific specimens from the Academy of Sciences. As they all converge on Henry’s mansion, they uncover his plot to flee the city with valuable possessions, including the rare Phoenix Crown.

In a final confrontation, Henry locks the women inside his mansion and sets it on fire, but they manage to escape—Gemma using her powerful lungs to rescue Reggie and Suling. The women emerge victorious as the city burns around them.

The story shifts to 1911, where the women, having rebuilt their lives, reunite in France. Alice, now a respected botanist, learns that Henry, now under a different name, plans to flaunt his infamous Phoenix Crown at a high-society party.

Suling, now a successful fashion designer, infiltrates the event with the help of Gemma and Alice.

Reggie, still haunted by her past, crashes the party to warn Henry’s new fiancée. In a climactic confrontation, the women force Henry to confess his crimes, leading to his eventual downfall.

In the aftermath, the women return to San Francisco, where they find peace and success in their respective fields, finally free from the shadow of Henry’s tyranny.

Characters

Gemma Garland

Gemma is an opera singer whose story arc showcases her growth from a struggling artist to a woman of independence and strength. Initially, Gemma is portrayed as someone vulnerable due to her financial instability and her dependence on others.

She falls into a romantic relationship with Henry largely out of desperation. Her migraines, which she allows to interfere with her decision-making, lead to her financial ruin when she entrusts her agent with her money.

However, Gemma is not without her talents, particularly her exceptional singing ability, which opens doors for her in the San Francisco opera scene. Her relationship with Henry becomes more complex when she learns of his darker side.

In the end, Gemma proves to be resourceful and courageous, especially during the earthquake and the final confrontation with Henry. Her decision to sing with Caruso in the destroyed city highlights her resilience, while her eventual marriage to George and their move to Buenos Aires mark her transformation from a dependent figure to one in control of her own life and artistic career.

Suling Feng

Suling is a seamstress who initially seems to be living under the strict control of her Third Uncle, pressured into an arranged marriage she doesn’t want. Her defiance of this traditional expectation sets her up as a character of quiet strength and independence.

She cross-dresses as a boy, signaling her willingness to adopt unconventional means to survive and avoid societal constraints. Suling’s romantic involvement with Reggie shows her capacity for deep love, but her world is disrupted by Reggie’s sudden disappearance.

Her relationship with Henry, although professional, leads her to uncover the truth about his crimes, culminating in her discovering that he has imprisoned Reggie. Suling’s bravery during the earthquake, and her tenacity in freeing Reggie from the asylum, highlight her fierce loyalty.

After the fire at Henry’s mansion, Suling’s ability to survive and thrive in New York and Paris as a fashion designer shows her evolution from a seamstress in San Francisco to an international figure in her field. Her role in the final confrontation with Henry underscores her as a character deeply committed to justice and the protection of those she loves.

Reggie/Nellie

Reggie is a painter who is introduced under the alias Nellie, revealing her complex identity. Her disappearance early in the novel creates a mystery that drives much of the plot.

Reggie’s relationship with Henry, a railroad tycoon and patron of the arts, initially brings her into the circle of high society. However, it quickly turns dark when she becomes a witness to his violent crime.

Her imprisonment in an asylum by Henry marks a dramatic turn in her life, where she suffers severe trauma. Despite this, Reggie’s love for Suling is strong enough to motivate Suling to risk everything to free her.

After her escape and Henry’s downfall, Reggie struggles with her artistic career, showing the lingering effects of her traumatic experience. By the end of the story, once Henry is dead and justice is served, Reggie regains her ability to paint.

Her final arc reveals a woman who has been through tremendous suffering but finds healing through her art and her relationships with the other women.

Henry Thornton/William

Henry Thornton, later known as William, is a railroad tycoon and patron of the arts whose charm and wealth mask a deeply sinister nature. At first, Henry appears to be a generous benefactor, offering support to both Reggie and Gemma in their artistic pursuits.

However, his character is gradually revealed to be manipulative and violent. His relationship with Reggie turns from romantic interest to something much darker when he locks her away in an asylum after she witnesses him commit murder.

His fear of fire, stemming from his own experience with being burned, becomes symbolic of his fear of losing control. Henry’s ultimate descent into madness is seen when he sets his mansion on fire with the four women trapped inside.

His final act of locking them in the conservatory and escaping with his valuables signifies his inability to accept responsibility for his actions. Henry’s eventual downfall at the hands of the four women, who expose his crimes at the party in France, shows that his power was built on lies and violence.

His suicide during the trial marks the end of his tyrannical hold over the women’s lives.

Alice Eastwood

Alice is a botanist whose role in the story contrasts with the other women due to her scientific focus. While Gemma, Suling, and Reggie are more directly involved in the arts, Alice’s passion for botany and her desire to save rare plant specimens from the California Academy of Sciences during the earthquake reveal her deep commitment to nature and knowledge.

Alice’s calm and analytical nature make her a stabilizing force in the group of women, often approaching problems with a practical mindset. Her fascination with Henry’s rare Queen of the Night flower serves as a metaphor for her quiet persistence and the fleeting nature of beauty, both in plants and in human lives.

Alice’s life after the earthquake takes her into nature in the Tahoe region, where she finds solace and fulfillment. Her eventual return to San Francisco and her participation in the final showdown with Henry in France demonstrate her loyalty to the women she has befriended, as well as her belief in justice and truth.

George

George is the local accompanist and eventual husband of Gemma. Though a more peripheral character compared to the women, George provides stability and emotional support for Gemma.

His practical approach to life and his dedication to music align with Gemma’s ambitions, allowing her to focus on her singing career. George’s role in finding Gemma after the earthquake, when he hears her singing in the streets, symbolizes his constant presence in her life as someone who listens and understands her deeply.

His move to Buenos Aires with Gemma and their subsequent marriage signify the couple’s joint commitment to their shared passion for music, as well as their desire to build a new life together away from the trauma of San Francisco.

Madam Ning

Madam Ning is an important figure in Suling’s life, as she was her late mother’s closest friend and a surrogate maternal figure. Madam Ning represents a connection to Suling’s past and her Chinese heritage, as well as a source of wisdom and strength.

Her role in the story becomes more active when she confronts Henry about an outstanding debt. This scene ultimately leads to her tragic death at his hands.

Madam Ning’s presence throughout the novel emphasizes themes of family loyalty and cultural identity. Her death serves as one of the final triggers for the women to take action against Henry.

Themes

The Complex Intersection of Art, Power, and Corruption: The Manipulative Influence of Patrons on Artists’ Autonomy and Well-being

One of the most intricate and troubling themes in The Phoenix Crown is the manipulation of artists by those who hold financial power. Henry Thornton, as a wealthy railroad tycoon and patron of the arts, exercises significant control over both Gemma and Reggie, exploiting their vulnerability as artists who rely on his support.

Gemma’s relationship with Henry evolves from financial dependence into a romantic entanglement, illustrating how easily artistic autonomy can be compromised by financial pressures. Henry’s control over Gemma’s career — taking over her financial management, arranging exclusive parties, and influencing her roles at the opera — is presented as a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, it provides her with opportunities. On the other, it strips her of independence.

For Reggie, Henry’s patronage is even more insidious, as he literally imprisons her to silence her after she witnesses him commit murder. The novel underscores how the power imbalance between wealthy patrons and dependent artists can lead to devastating consequences, including the loss of freedom, identity, and safety.

It calls into question the ethical dimensions of patronage, highlighting that artistic success, especially for women in this era, often came at the cost of their autonomy, and in Reggie’s case, her mental well-being.

Gendered Expectations and the Fight for Personal Agency Amidst Societal Oppression

Another key lesson embedded in the novel is the characters’ constant battle against the suffocating societal expectations imposed on women in the early 20th century. Suling Feng’s struggle to avoid an arranged marriage orchestrated by her Third Uncle showcases the cultural pressures placed on women to conform to traditional roles, even when such roles conflict with their personal desires and autonomy.

Similarly, Gemma, Reggie, and Alice all grapple with the limitations placed on them because of their gender. Gemma’s need to rely on a male patron to advance her career reflects the systemic barriers women faced in securing financial independence.

Her entanglement with Henry becomes symbolic of how women’s bodies and talents were often commodified in patriarchal societies. Reggie’s imprisonment further amplifies this theme, showing how women who challenge powerful men, or even witness their wrongdoings, can be silenced and oppressed.

The novel offers a sharp critique of how gendered expectations constrict personal agency. It illustrates that the characters’ true power lies in their refusal to comply with these norms.

Their reunion and collective action against Henry in the latter half of the novel serve as a metaphor for their reclamation of agency. Through their victories, the authors underscore the importance of female solidarity in overcoming patriarchal oppression.

Trauma and Its Lingering Shadows: The Path to Healing Through Art, Relationships, and Confrontation

The Phoenix Crown delves deeply into the psychological trauma endured by its characters, particularly Reggie, whose experiences of being imprisoned and silenced by Henry leave her unable to paint seriously for years. Trauma, in this narrative, is not just an emotional scar but a force that stifles creativity and self-expression.

Reggie’s artistic paralysis reflects the way trauma can strip an individual of their identity, purpose, and passion. Yet, the novel also explores the gradual process of healing, emphasizing that recovery is not linear but can be catalyzed by confronting the past.

Reggie’s eventual return to painting after Henry’s death serves as a testament to the redemptive power of facing one’s demons. The novel shows that healing often requires more than time; it demands confrontation, whether it be emotional, artistic, or physical.

Gemma’s own journey parallels Reggie’s as she finds solace and strength through her music, even as she contends with the betrayal and exploitation by Henry. Their creative outlets, coupled with the support of their friendships, become the means through which they reclaim their lives from the shadows of trauma.

Ultimately, the novel teaches that while trauma may cast long shadows, there is a path to healing that involves not only personal courage but also the restoration of relationships and creative purpose.

The Fragile Line Between Identity and Disguise: The Use of Gender and Class Performance as a Means of Survival

The theme of identity and disguise is intricately explored through Suling’s character, who dresses as a boy to navigate the societal constraints placed upon her as a woman and a lower-class seamstress. This disguise is not only a means of survival but also an act of rebellion against the rigid gender and class systems of the time.

The novel complicates the idea of identity by showing how characters are forced to adopt certain roles or disguises to achieve their goals or escape danger. Gemma, too, performs an identity when she becomes Henry’s lover and socializes in circles of wealth and power that are foreign to her.

These performances reveal the fluidity and fragility of identity, as the characters must constantly negotiate their true selves with the personas they adopt to survive in a world that marginalizes them based on gender, class, and race. However, this constant shifting of identity takes its toll, as Suling and Gemma both struggle with a sense of displacement, unsure of who they truly are amidst the roles they are forced to play.

The novel highlights the emotional and psychological cost of these disguises, suggesting that the struggle for authenticity is a difficult but essential one.

Nature as a Silent Witness and Agent of Rebirth: The Symbolism of the Queen of the Night Flower and the Phoenix Crown

Nature plays a symbolic role throughout the novel, often acting as a silent witness to the characters’ struggles and transformations. The Queen of the Night flower, which blooms only once a year, serves as a metaphor for the rare and fleeting opportunities for the women to seize control of their lives.

Its brief, extraordinary bloom mirrors the moments of agency and self-realization that the characters experience in their battle against Henry and societal constraints. The Phoenix Crown, another key symbol, represents not only Henry’s greed and corruption but also the resilience of the women.

Like the mythological phoenix that rises from its ashes, the women, too, emerge from the literal and metaphorical fires of their lives, stronger and more self-assured. The earthquake itself can be seen as an agent of rebirth, as it destroys the old structures—both physical and societal—that trap the women.

This allows them to escape, confront their pasts, and rebuild their futures. Through these natural and symbolic elements, the authors emphasize the cyclical nature of destruction and renewal, suggesting that personal growth often comes from confronting devastation head-on.