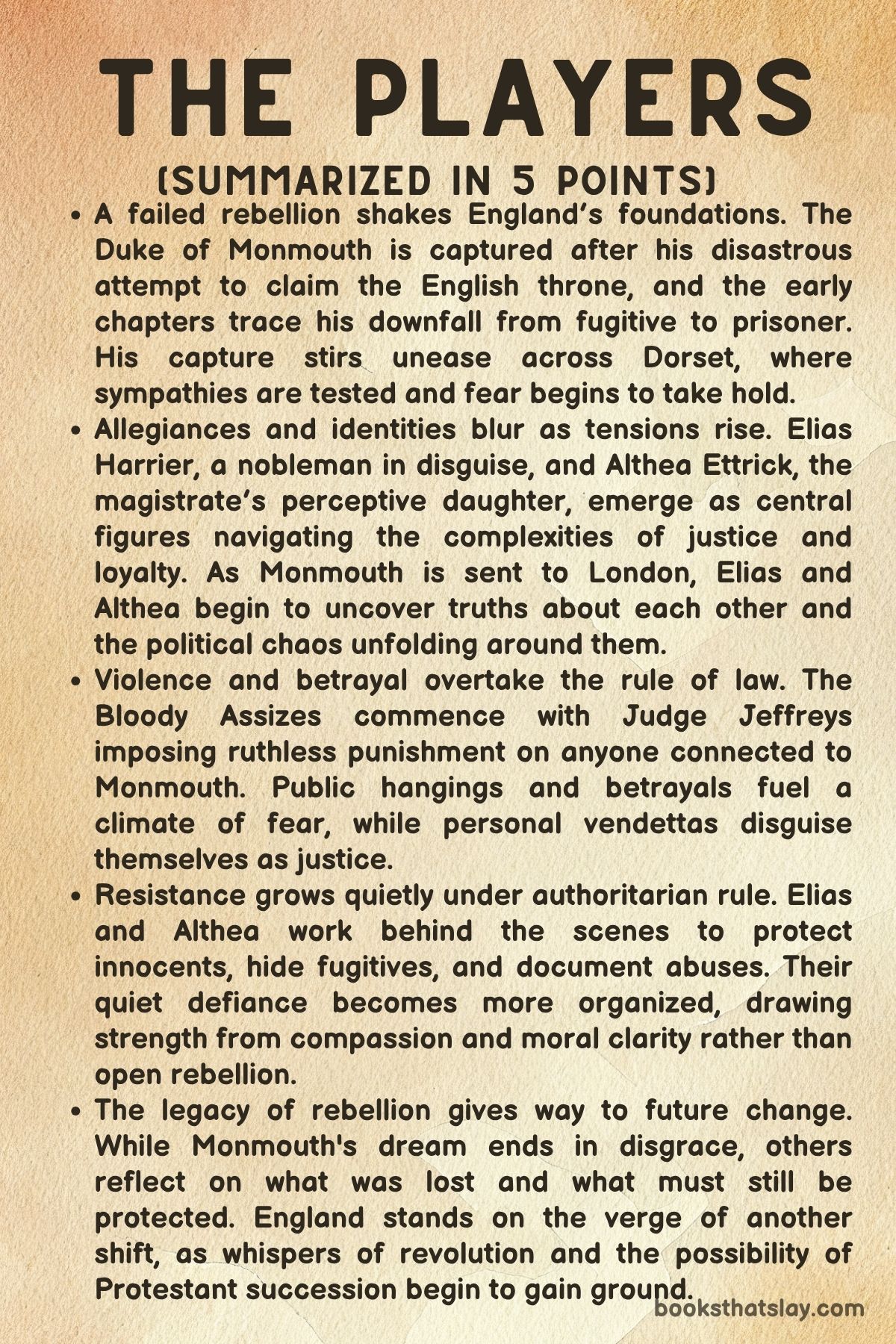

The Players by Minette Walters Summary, Characters and Themes

The Players by Minette Walters is a richly imagined historical novel exploring the turbulence of late 17th-century England, particularly the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685 and the subsequent Bloody Assizes. Rather than simply recounting the events, Walters offers a character-driven narrative that interrogates the limits of justice, the power of conscience, and the personal costs of political ambition.

At the heart of the story is Elias Granville, a nobleman working in disguise, who becomes the moral compass in a world teetering on the edge of tyranny. With an expansive cast, intricate political maneuvering, and deep emotional undercurrents, the novel presents both a vivid portrayal of the era and a meditation on how private choices shape public history.

Summary

The Players opens in The Hague in 1685, where an exiled James Scott, Duke of Monmouth—the illegitimate son of the late King Charles II—plots a rebellion against his Catholic uncle, King James II. A secret observer, Elias Granville, once a crown envoy, warns Monmouth that his plans are doomed due to lack of funds and support.

Despite this, Monmouth proceeds, believing he is destined to lead a Protestant uprising in England. After his failed rebellion and humiliating defeat at Sedgemoor, Monmouth is discovered in hiding and arrested.

His capture, overseen by the rational and empathetic Reverend Houghton, reveals a man physically broken yet clinging to fading dignity. Even in defeat, he asks for mercy not for himself but for his followers.

Monmouth is brought before magistrate Anthony Ettrick, whose brilliant but physically disabled daughter, Althea, helps with the legal questioning that confirms his identity. Despite Ettrick’s fair-minded approach, Monmouth’s fate is sealed.

He pleads for leniency for his men, but the growing paranoia of King James II has already set a brutal tone. Althea becomes a pivotal observer and analytical voice, later suspecting that the parson who aided Monmouth is actually Elias Granville, a former comrade of the Duke.

Her deduction proves accurate, and her reunion with Elias and his mother Jayne rekindles a warm but intellectually charged relationship that reveals Althea’s sharp insight and deep integrity.

As the rebellion’s aftermath unfolds, the political climate hardens. Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys is dispatched to lead the Bloody Assizes, a sweeping legal purge of Monmouth’s supporters.

Elias, embedded in the system under a false identity, seeks to mitigate the cruelty from within. He debates justice with Jeffreys, who insists that legal terror is more effective than mercy.

Jeffreys exemplifies cold, doctrinal authority, while Elias represents moral resistance. They are ideological foils, engaged in philosophical and literal battles about the nature of law and justice.

Elias tries to save the innocent through subversive tactics, including sending coded Latin warnings to imprisoned rebels to resist manipulated plea bargains. These warnings, written by Althea, are sent to the lawyer Matthew Bragg.

Bragg’s trial becomes emblematic of the system’s corruption. Although he mounts a rigorous legal defense, Jeffreys ensures a guilty verdict through intimidation and manipulation, sentencing him to a gruesome death.

The show trials continue in Dorchester, with Jeffreys relishing the power of the courtroom and dismissing any moral counterpoint. Althea, Elias, and Jayne continue to oppose his cruelty quietly, preserving dignity and moral clarity in a system that increasingly rewards fear and obedience.

The narrative then shifts to a broader national scale with the arrival of Prince William of Orange’s fleet on the English coast during the Glorious Revolution. Elias, acting again as a bridge between nations and ideologies, helps frame the invasion not as a military coup but a constitutional correction.

The Dutch army’s discipline and respect for civilians contrast starkly with the earlier chaos of Monmouth’s rebellion, signaling a new chapter in English governance. William’s strategy focuses on advancing unopposed, encouraging defection within King James’s army and winning over public opinion through controlled messaging and carefully crafted proclamations.

With William and Mary crowned as joint sovereigns and Parliament newly empowered by the Bill of Rights, Elias reflects on how Monmouth’s failure helped clear the path for a more peaceful transition to constitutional monarchy. Despite the personal cost, including his own disillusionment and the lives lost in the rebellion, Elias finds some satisfaction in the institutional changes that echo his father’s long-held belief in a monarchy accountable to law.

As a final act of redemption, Elias and Althea visit Lord Jeffreys in the Tower of London. Once a towering symbol of judicial cruelty, Jeffreys is now a dying man, wracked by illness and regret.

Though initially skeptical, he is moved by their compassion. Althea, once unseen by society due to her disability, proves to be a moral force as she confronts Jeffreys with truth rather than flattery.

Their presence allows Jeffreys to die with a measure of peace, having confessed his regrets and acknowledged his moral failings.

In the novel’s closing scenes, Elias returns to a quieter life, rejecting courtly honors in favor of ongoing diplomatic service. Althea steps into public life for the first time in years, her intellectual prowess finally acknowledged.

Their bond, though not romanticized, signals a convergence of intellect, courage, and empathy—values that quietly shape the next generation.

The Players is not just a historical recounting of the Monmouth Rebellion and Glorious Revolution, but a deeply personal story about the characters who shape, resist, and ultimately humanize the march of history. Through Elias, Althea, and others, Walters interrogates the cost of ambition, the strength of conscience, and the enduring struggle to reconcile justice with power.

Characters

Elias Granville

Elias Granville stands at the heart of The Players as a man caught between allegiance, integrity, and compassion. Once a nobleman and royal envoy, he returns to England in secret, donning the disguise of Reverend Harrier to maneuver within the crumbling political and moral landscape following Monmouth’s failed rebellion.

Elias is driven not by glory or ambition but by a profound sense of justice and responsibility. His interactions with Monmouth reveal both loyalty and deep disillusionment.

He sympathizes with Monmouth’s cause but condemns his arrogance and impulsiveness. Elias’s character is marked by an unwavering moral compass—evident in his commitment to humane treatment of prisoners, his revulsion at Judge Jeffreys’s cruelty, and his strategic yet ethical resistance to tyranny.

He demonstrates intellectual sharpness, diplomatic skill, and emotional restraint, particularly in his coded warnings to prisoners and his final acts of mercy toward Jeffreys. Elias’s arc moves from hidden manipulation to quiet heroism, showing how personal sacrifice and clarity of principle can resist systemic brutality.

His bond with Althea also marks a tender shift from solitude to companionship rooted in mutual respect.

Althea Ettrick

Althea Ettrick is one of the novel’s most intellectually formidable characters, emerging as a silent force behind the scenes. Physically disabled and reclusive, she compensates with a piercing intellect and legal astuteness that rival the era’s best minds.

As the daughter of magistrate Anthony Ettrick, she assists her father in identifying Monmouth through carefully crafted questions, demonstrating a clinical grasp of logic and human behavior. Althea’s most transformative moment comes through her interaction with Elias, in whom she recognizes both nobility and subterfuge.

Her investigative prowess leads her to unmask Elias’s true identity, not out of vanity but from an unrelenting pursuit of truth. Her courage to step outside her home after years of seclusion underscores her internal growth.

By the novel’s end, Althea is not just a keen observer of justice but an active participant in it, especially in her visit to the imprisoned Jeffreys. Her ability to confront him with calm truth and controlled compassion redefines power, showing that strength lies in clarity and kindness.

She becomes both moral anchor and emotional equal to Elias.

James Scott, Duke of Monmouth

The Duke of Monmouth is a tragic embodiment of misguided ambition and squandered potential. As the illegitimate son of Charles II, Monmouth is imbued with royal entitlement and the fantasy of popular support.

His decision to rebel against King James II is not born of strategic acumen but of desperation and a desire to reclaim perceived rights. Monmouth’s paranoia, grief, and arrogance cloud his judgment, leading him to launch a rebellion with insufficient resources and a false belief in English loyalty.

His capture, weakened and starving, humanizes him as a man destroyed by his dreams. Yet even in defeat, he clings to a sliver of dignity, accepting blame for his followers and pleading for their lives.

In his final days, his desperation overtakes pride—offering to convert to Catholicism to save himself—revealing the fragility of his convictions. Monmouth’s arc serves as a counterpoint to Elias: where Elias is deliberate and principled, Monmouth is impulsive and prideful.

His downfall is not only a political failure but a personal unraveling, tragic in its exposure of human vulnerability.

Lord George Jeffreys

Lord Jeffreys emerges as the most polarizing figure in The Players, notorious for his role in the Bloody Assizes. Initially introduced as a drunk and erratic tyrant, Jeffreys is the face of institutional cruelty masquerading as legal order.

He believes unwaveringly in the law’s supremacy, using it as a tool of fear and oppression. His courtroom demeanor is theatrical, his judgments harsh and performative.

Jeffreys is unrepentant in public, eager to destroy rebels to consolidate royal power. Yet, in private, especially in the presence of Elias and Jayne Harrier, his façade begins to crack.

His interactions with Jayne reveal his bitterness and internal torment, and his decline in the Tower of London exposes the man beneath the robes—a physically broken figure riddled with regret. Althea and Elias’s compassion enables him to confront his legacy, making his final days a rare opportunity for redemption.

His transformation from tyrant to penitent allows the novel to explore justice as not merely retributive but capable of mercy and introspection. Jeffreys’s death, surrounded by empathy, serves as a reminder that humanity can survive even the most destructive exercise of power.

Jayne Harrier

Jayne Harrier, Elias’s mother, brings quiet strength and maternal clarity to the narrative. A healer and noblewoman, she navigates the dangerous political climate with wisdom and grace.

Her treatment of Jeffreys, despite his prior offenses, reveals a belief in duty over judgment. Jayne’s conversations with Jeffreys are piercing, laced with irony and insight, reminding him—and the reader—that moral decay often hides beneath ceremonial grandeur.

Her bond with Althea is rooted in shared memory and emotional intelligence, helping coax Althea into re-engaging with the world. Jayne represents the moral foundation from which Elias draws his integrity.

Her character is both nurturing and formidable, showing how strength can be wielded with subtlety and compassion.

Anthony Ettrick

Magistrate Anthony Ettrick represents the rational, procedural side of justice. Though limited by age and conventionality, he is earnest in his attempt to uphold law with fairness.

He relies on Althea for intellectual guidance, indicating a humility that sets him apart from many of his contemporaries. Ettrick’s measured conduct during Monmouth’s identification contrasts sharply with Jeffreys’s brutality.

He is a transitional figure, bridging the rigid old order with the emergent values of empathy and reason, embodied by Althea and Elias.

Lord Lumley and Sir William Portman

Lord Lumley and Sir William Portman are emblematic of the rivalry and self-interest that taint noble and military affairs. While both are responsible for Monmouth’s capture, their squabble over who deserves credit reduces their heroic veneer to vanity.

Portman is more rational and dutiful, while Lumley’s behavior is often brash and self-serving. Their presence in the narrative serves to critique the pettiness that undermines genuine statesmanship during times of national crisis.

Matthew Bragg

Matthew Bragg, the principled lawyer who becomes a martyr to the judicial cruelty of the age, represents integrity in the face of systemic injustice. His refusal to capitulate to Jeffreys’s coercive tactics and his calm, reasoned defense illustrate the futility of justice when the courtroom is corrupted.

His trial is one of the most searing indictments in the novel, exposing how the law can be weaponized against those who believe in it most. Bragg’s death is symbolic—less a failure of his own than a testament to the moral vacuum of the regime he opposed.

Jan Hendriksen

Jan Hendriksen serves as Elias’s Dutch contact and confidant, offering both logistical support and a wider perspective on European politics. He is pragmatic, calm, and perceptive, ensuring that William of Orange’s campaign is executed with tact and restraint.

While not emotionally central, his character underscores the geopolitical dimension of the narrative and helps illuminate Elias’s strategic acumen. He is a steadying presence in the storm, anchoring the narrative’s broader historical transitions.

Themes

Authority and Tyranny

Power in The Players is consistently portrayed as a double-edged force—capable of preserving order but easily corrupted when untempered by conscience. This theme manifests most clearly in the character of Lord Jeffreys, whose judicial authority is exercised not with fairness, but with cruelty and political zeal.

His interpretation of justice is devoid of empathy or nuance; he wields the law as an instrument of fear rather than a path to equity. Elias Granville’s philosophical resistance to this approach underscores the novel’s moral argument: that unchecked authority becomes tyranny when it ignores context, motive, or proportionality.

The Bloody Assizes, which Jeffreys administers, are not merely legal proceedings—they are acts of vengeance cloaked in legitimacy. Through Elias’s interactions with Jeffreys, the reader is reminded that legal power divorced from ethical reflection leads to brutality.

Even the monarchy is implicated, with King James II portrayed as demanding loyalty through intimidation, fostering obedience not through reverence but through terror. The story does not dismiss the need for governance but questions how power is applied, by whom, and for what purpose.

In showing Jeffreys’s eventual physical and moral collapse, the book delivers a stark message: tyrannical authority is ultimately self-consuming and isolating. It leaves in its wake only fear, resentment, and a legacy of cruelty.

Conscience and Moral Responsibility

Elias Granville’s journey in The Players revolves around the struggle to reconcile loyalty to country with loyalty to moral principle. This internal conflict surfaces repeatedly, especially in his interactions with both Monmouth and Jeffreys.

Elias is not a revolutionary in the traditional sense; he operates within institutions yet seeks to hold them accountable to humane standards. His covert efforts to save prisoners from Jeffreys’s deceitful plea bargain offer, even at personal risk, highlight his commitment to truth and justice over blind allegiance.

Conscience in the novel is portrayed as a quietly resilient force, often in opposition to institutional mandates. Althea, too, is a figure of moral insight, using her intellect to see through facades and urge ethical choices without seeking recognition.

The contrast between Elias and Jeffreys illustrates two models of duty: one rooted in reflective, humane judgment, the other in rigid, punitive obedience. Importantly, the novel resists portraying Elias as infallible; his moral clarity is hard-won and filled with emotional cost, particularly in his failed attempt to sway Monmouth or save others.

This depth reinforces the complexity of moral responsibility—not as a set of idealistic proclamations, but as a lived struggle requiring courage, sacrifice, and an acceptance of imperfection.

Justice and Legal Manipulation

Justice in The Players is frequently portrayed as compromised by ambition, ideology, and fear. The legal system, represented most forcefully by Lord Jeffreys, is weaponized not to seek truth but to solidify political control.

Trials become performances, predetermined and shaped by the Crown’s objectives rather than the facts. Bragg’s courtroom experience is emblematic: his careful, reasoned defense collapses under the weight of Jeffreys’s aggression and rhetorical dominance.

Even language—such as the coded Latin message sent by Althea—is shown to be both a shield and a weapon in this legal battlefield. The promise of mercy is manipulated to extract guilty pleas, only to lead to execution, betraying any semblance of good faith.

Yet, the narrative doesn’t entirely lose faith in justice. It presents an alternative vision in Elias, Althea, and even in the later acts of mercy shown to Jeffreys himself.

The theme suggests that justice is not a static institution but a dynamic ethical process, one that must be protected from political corruption and delivered by individuals who are not merely functionaries of power but guardians of fairness. In critiquing the spectacle of law during the Bloody Assizes, the novel warns of what happens when justice becomes subordinate to spectacle, vengeance, or fear.

Redemption and Human Complexity

The transformation of Lord Jeffreys from feared tyrant to a broken man seeking understanding is one of the novel’s most poignant meditations on human complexity. Initially the embodiment of cruel authority, Jeffreys is revealed, in his final days, to possess layers of regret, brilliance, and loneliness.

His interactions with Althea and Elias—especially in the Tower of London—strip away his defenses. They do not absolve his past, but they acknowledge his humanity.

Elias and Althea extend compassion not because Jeffreys deserves it by moral accounting, but because the act of mercy itself reaffirms their own humanity. This approach to redemption is neither sentimental nor simplistic.

Jeffreys is not reimagined as virtuous, but as a man capable of self-awareness and remorse when shown empathy and truth. The theme argues that people are rarely defined by single acts alone.

Redemption is made possible through confrontation with the self, and through the willingness of others to see beyond roles and reputations. The final scenes suggest that dignity can be reclaimed, even in disgrace, when one is seen as a person rather than merely a symbol of power or failure.

Through this lens, redemption is not a reward but a transformation rooted in mutual recognition.

Identity, Disguise, and Truth

Throughout The Players, the fluidity of identity—both literal and symbolic—drives many of the story’s tensions. Elias’s use of disguises, Monmouth’s failed attempt to escape as a shepherd, and the parson’s concealed noble heritage all point to the idea that truth and identity are not always aligned with appearance.

Althea’s capacity to see through Elias’s disguise reflects the power of perception over presentation. Yet, identity here is not just about physical disguise.

It is about personal allegiance, political positioning, and moral stance. Monmouth’s tragedy lies in his inability to reconcile his self-image with his capabilities.

He imagines himself a leader of men but lacks the strength or foresight to command real loyalty. Jeffreys clings to the identity of a righteous judge, even when his actions betray it.

Elias embraces ambiguity, choosing actions over titles, and by doing so, finds a steadier form of truth. The theme highlights how characters either hide from or construct their identities to match their needs, ambitions, or fears.

The eventual unmasking—literal or figurative—becomes not just a revelation of fact, but a moral reckoning. In a world governed by appearances and power dynamics, truth is not what is declared but what is understood through character, action, and choice.

Resistance and the Ethics of Loyalty

Loyalty in the novel is tested across axes of family, nation, belief, and self-respect. For Elias, resistance is not loud or inflammatory, but strategic, quiet, and principled.

His opposition to Jeffreys and the Crown is not rooted in rebellion for its own sake, but in a belief that loyalty must include ethical integrity. This positions him in stark contrast to those who either betray for gain or comply out of fear.

Even Althea’s loyalty—to justice, to her father, to truth—demonstrates a resistance to apathy. The theme questions the simplistic dichotomy of traitor versus loyalist.

Monmouth, for instance, sees himself as loyal to England by opposing a Catholic king, yet his rebellion leads to destruction, and his plea for clemency reveals a wavering conviction. Resistance in The Players is not framed as dramatic insurrection but as ethical action under pressure.

It’s in the decision to write a letter, to speak the truth in court, to tend to the sick regardless of their crimes. The novel argues that loyalty gains meaning only when it withstands pressure to conform blindly, and when it is aligned with moral clarity rather than convenience or fear.