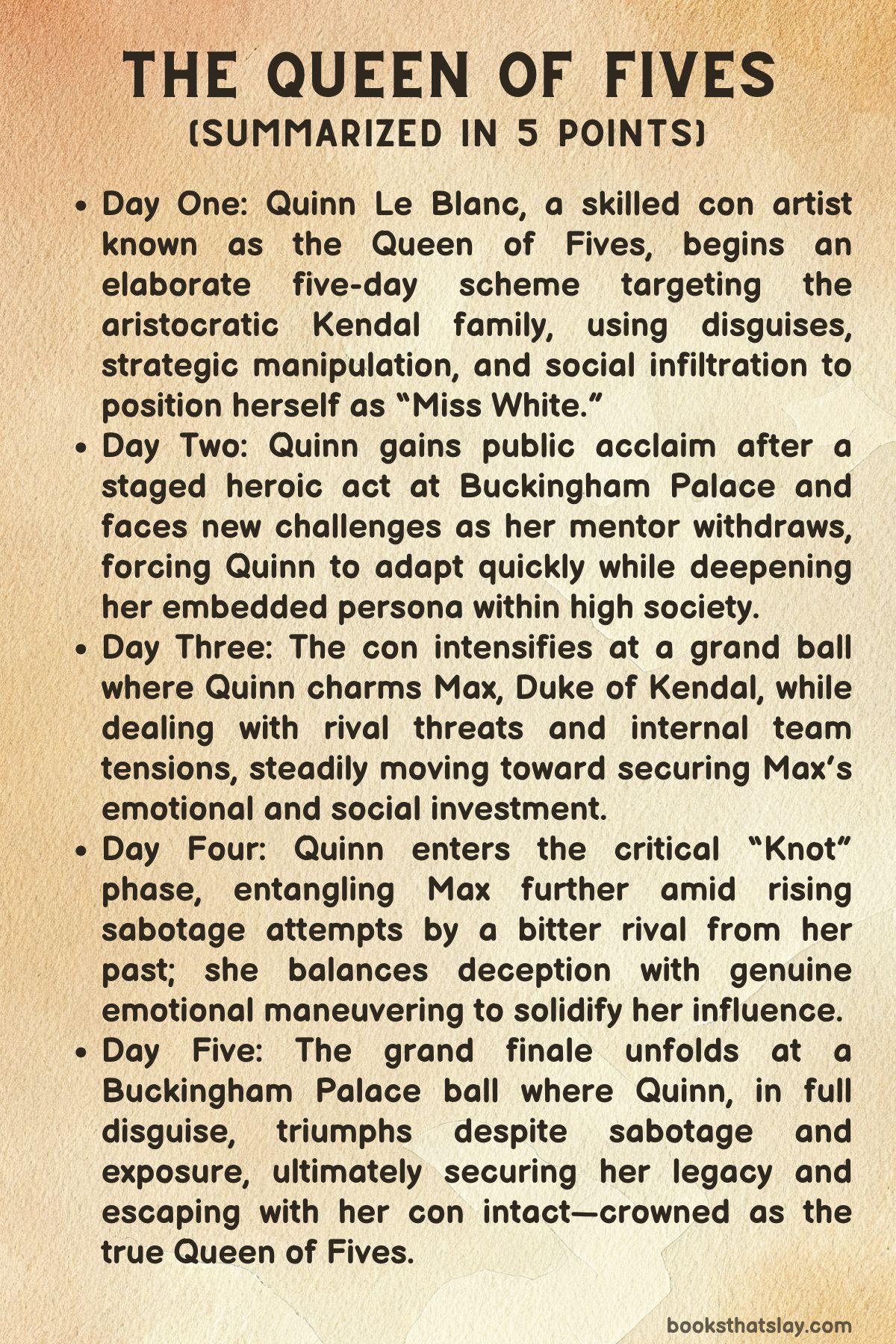

The Queen of Fives Summary, Characters and Themes

The Queen of Fives by Alex Hay is a stylish, sharply constructed historical novel set in the stratified world of Victorian England. It follows the ambitious and audacious Quinn Le Blanc, a con artist of unmatched skill who operates under the codename “Queen of Fives.”

Through a multi-day heist that doubles as a societal infiltration, Quinn sets her sights on the noble Kendal family, inserting herself into their world of secrets, debts, and crumbling legacies. The story thrives on misdirection, shifting alliances, and veiled identities, balancing high society’s elegance with the criminal underworld’s cunning. At its core, the novel explores power, performance, and reinvention.

Summary

The novel opens on Quinn Le Blanc’s wedding day in 1898, a moment of ceremonial splendor cloaked in lies. Her gown is not a romantic symbol but a calculated display of dominance, her every move choreographed to align with her broader con.

As she prepares for the wedding, she reflects on how she orchestrated this spectacle through a plan that began five days earlier in Spitalfields, where she reigns over a female-led criminal hub called the Château.

Back in Spitalfields, Quinn initiates her most daring scheme yet. Alongside her precise and rule-bound partner Mr.

Silk, she prepares to introduce a false identity into London’s elite: “Miss Quinta White,” an heiress with a mysterious background and fabricated wealth. Their mark is the Kendal family, especially Maximilian, the reserved and powerful Duke of Kendal.

The operation relies on societal performance, reputation manipulation, and a network of allies like Mrs. Airlie, Quinn’s former mentor and headmistress of a finishing school for female con artists.

Persuading Mrs. Airlie to participate proves challenging but vital, and Quinn wins her over by promising a written contract and a taste of the power she once held.

As part of the plan, Quinn stages a dramatic fake assassination attempt during a royal presentation at Buckingham Palace. An accomplice, Maud Dunuvar, pretends to attack a dignitary, and Quinn saves the day in front of the royal court, instantly earning admiration and securing a reputation that opens doors to the highest levels of society.

Her fabricated identity is cemented, and the Kendals take notice.

The operation moves into its next phase, “the Intrusion. ” Disguised in a range of roles—flower seller, maid, chimney sweep—Quinn infiltrates Kendal House to gather intelligence.

Her findings reveal a fractured household: Lady Kendal is imposing and athletic, Max’s bedroom is oddly sterile and childlike, and his sister, Victoria “Tor” Kendal, lives in an opulent yet isolated suite. Quinn determines that Tor, unmarried and financially vulnerable, could be her point of access.

Tor, meanwhile, grapples with growing anxiety over her position. Max’s potential marriage threatens her status and finances, as the entailed estate could pass to a future duchess.

When she learns Max is trying to access her funds, Tor turns to her solicitor and considers legal maneuvers to protect herself. Her investigation uncovers unsent love letters penned by Max—romantic, intimate, and addressed ambiguously.

These revelations complicate her view of her brother, revealing a deeply private inner world that may be taboo in nature. Tor becomes determined to defend both her independence and her family’s reputation.

Quinn receives an invitation to the Kendal ball, a society event that may determine the success or failure of her con. There, she dances with Max, who surprises her by proposing a marriage of convenience rather than passion.

He implies that love is not something he can pursue openly and that their engagement would benefit them both. Quinn agrees, seeing the tactical advantage, even as she begins to sense the emotional currents that complicate Max’s demeanor.

The engagement becomes public knowledge, but not everyone is pleased.

Lady Kendal immediately sets out to dismantle the arrangement. She views Quinn as an outsider and manipulates Tor into attempting to sabotage the engagement by hinting at scandalous secrets about Max’s affections.

Tor, already fragile, feels further alienated and betrayed when her stepmother threatens her financial autonomy and pressures her to intervene. Meanwhile, Mr.

Silk is kidnapped by a rival from the Château’s past—a woman who once vied for leadership and now seeks revenge. She demands his allegiance and forces him to betray Quinn by handing over the Château’s Rulebook and severing Quinn’s support from Mrs. Airlie.

As the wedding day approaches, tensions peak. The Kendal family estate is secretly bankrupt, and their financial advisor, Willoughby, has orchestrated a scheme to access Quinn’s wealth through the marriage settlement.

Lady Kendal and Willoughby’s conspiracy rests on manipulating Max and sacrificing Tor’s financial interests to keep the family afloat.

Tor awakens drugged in the attic, imprisoned in a grotesque space filled with mechanized dolls—secret bombs. Lady Kendal reveals herself as Martha, a former member of Quinn’s guild and one-time Queen of Fives.

She has been operating a long con, posing as a noble philanthropist while enacting a plan of revenge against the Château and its current queen, Quinn. Her elaborate scheme includes sacrificing her own household if it means regaining control of her criminal legacy.

Quinn, Silk, and their remaining allies execute a desperate counterstrike. They uncover Lady Kendal’s full plan and race against time as she ignites the explosives hidden within the dolls.

Kendal House erupts in chaos, stairwells collapse, and smoke fills the air. In the confusion, Quinn rescues Tor and helps the others escape just as the building detonates, effectively erasing the evidence and Lady Kendal herself, who disappears into the fog.

In the aftermath, Parliament dissolves the entail to allow the family to retain some property. The Duke and Tor begin rebuilding what remains of their lives and legacy.

Though the marriage never happens, Max and Quinn share a final conversation full of mutual understanding and unspoken emotion. They part as collaborators, no longer constrained by society’s rules or criminal syndicates.

Quinn walks away from the wreckage, finally free of the labels that defined her. She is no longer just a con artist, a bride, or a queen.

She becomes a woman who has rewritten her story entirely—not through deceit, but through survival, confrontation, and choice. The ticking clock that once ruled her life is gone, replaced by the quiet certainty of self-determination.

Characters

Quinn Le Blanc

Quinn Le Blanc is the magnetic, cunning, and psychologically layered protagonist of The Queen of Fives. Known as the Queen of Fives, she navigates the world as both a master con artist and an astute observer of society’s facades.

Her life is defined by disguise, not just as a physical transformation, but as an existential survival tactic. From the outset, Quinn is depicted as a woman in total control of her image—her wedding, her gown, even her very presence in aristocratic society is a calculated performance.

Beneath the glamor and confidence, however, lies a character shaped by abandonment, ambition, and relentless self-discipline. Raised within the female-led criminal guild known as the Château, Quinn lives by the Rulebook, but also constantly tests its boundaries.

Her internal conflict between power and vulnerability surfaces as she forms an uneasy connection with the Duke of Kendal and later confronts betrayal from Mr. Silk.

Quinn evolves over the course of the novel from a woman obsessed with climbing and outwitting society, to someone who seeks autonomy not through deception, but through truth and survival. Her ultimate shedding of the Queen of Fives persona is not a defeat, but an act of reclamation, choosing selfhood over performance.

Lady Victoria “Tor” Kendal

Lady Victoria Kendal, or Tor, is one of the most compelling figures in The Queen of Fives, a woman born into aristocracy but consistently pushed to its margins. At thirty-five, she has neither married nor yielded her power, a choice that renders her both admirable and vulnerable in a society designed to sideline unmarried women.

Tor is fiercely independent, deeply loyal to her family home, and protective of her financial autonomy. Her resistance to the patriarchal pressures exerted by her stepmother, her brother, and society at large marks her as both a threat and an anomaly within the Kendal family.

As she uncovers Max’s hidden romantic life and the financial manipulations around her, she is thrust into an emotional and moral crisis. Her captivity in the attic—along with the grotesque symbolism of the bomb-laden dolls—cements the theme of women being silenced and controlled by both family and societal machinations.

By the novel’s end, Tor stands as both a survivor and a moral compass, reclaiming her position alongside her brother in the reconstruction of their legacy.

Maximilian, Duke of Kendal

Maximilian, or Max, the Duke of Kendal, is a man caught between expectation and emotional truth. Initially introduced as aloof and dutiful, Max slowly reveals an interior world of longing and repression.

His reluctance to marry is not rooted in pride but in a profound, secret love that would be socially catastrophic if revealed. Max’s character is shaped by constraint—by duty to the estate, by the pressure to marry for alliance, and by the emotional burdens imposed by his stepmother.

His offer to Quinn is emblematic of his internal dissonance: a marriage in name only, which reflects both his desperation and a glimmer of trust in her. He is neither hero nor antagonist, but a figure whose tragedy lies in the limited choices afforded him by his birth.

His transformation comes not through romantic fulfillment, but through devastation—watching his estate implode and discovering the depth of manipulation within his household. By joining forces with Tor and working toward rebuilding, Max steps into a new kind of leadership, one rooted in truth rather than appearance.

Lady Kendal / Martha

Lady Kendal, formerly known as Martha, is the novel’s central antagonist and a complex mirror image of Quinn. Her public persona—a poised dowager duchess and philanthropic aristocrat—masks her true identity as a former con artist and the once-exiled Queen of Fives.

Her return to power is a calculated revenge plot, aiming to dismantle the very society that once rejected her. She is both terrifying and brilliant, wielding societal norms as weapons and manipulating everyone around her—including Max, Tor, and Willoughby—to serve her ends.

Her ultimate plan, involving bombs disguised as dolls and a catastrophic detonation of Kendal House, is gothic and grotesque, underlining her descent into obsession and destruction. Yet, even in her villainy, Lady Kendal reflects the harsh truths of a world that denies women legitimate pathways to power.

She is what Quinn could have become—consumed by the game, unable to distinguish identity from performance. Her defeat is symbolic not only of her personal downfall but of an old regime of deception and vengeance collapsing under its own weight.

Mr. Silk

Mr. Silk is Quinn’s longtime collaborator, mentor, and ultimately, her betrayer.

A figure of order, precision, and emotional restraint, Silk embodies the law-bound ethos of the Château—where loyalty to the Rulebook supersedes personal affection. His role throughout the novel is multifaceted: he orchestrates cons, guides Quinn’s moves, and holds the strategic threads of the plot together.

Yet, when faced with coercion by a rival queen, Silk fractures. His decision to betray Quinn by returning the Rulebook and undermining her support network is devastating, not only because it threatens the operation, but because it represents a personal rupture.

Silk is not driven by malice but by fear and hierarchy, his betrayal highlighting the brittle foundations upon which criminal alliances are built. His character arc serves as a cautionary tale about loyalty without love and power without vision.

Mrs. Airlie

Mrs. Airlie is the headmistress of the Château’s finishing school and an emblem of legacy and tradition within the con-artist world.

She is both a maternal and authoritarian presence in Quinn’s life. Her initial reluctance to participate in Quinn’s new scheme is rooted in a distrust of Quinn’s ambition and the risks it poses to the sanctity of the Château.

Their relationship is one of tension and reluctant admiration, underscored by generational divides. While she does agree to act as Quinn’s chaperone, her allegiance always feels provisional.

Mrs. Airlie represents the old guard of the Château—more pragmatic, more conservative, and ultimately, more survival-oriented.

Though she is not central in the climactic confrontation, her presence early in the story helps define the moral and tactical boundaries Quinn must either adhere to or defy.

Willoughby

Willoughby is a shadowy but pivotal player within the Kendal estate’s financial web. He functions as both advisor and manipulator, orchestrating schemes under Lady Kendal’s command and ensuring Max remains constrained by duty and debt.

His failure to produce payment at the marriage settlement exposes his complicity in the estate’s financial ruin and accelerates the novel’s climax. Willoughby is emblematic of the silent rot at the heart of power—his presence subtle, his motives veiled, and his allegiance always to the status quo, even when that status is corrupt.

Maud Dunuvar

Maud Dunuvar, though a minor character, plays a vital role in executing Quinn’s early plans. Her participation in the staged assassination attempt at Buckingham Palace is a dramatic performance that sets the entire con into motion.

Loyal, daring, and committed to the cause, Maud embodies the spirit of sisterhood and risk that defines the Château’s operatives. She is a testament to the teamwork and trust that underpin Quinn’s operations—even as those structures are later betrayed.

Themes

Identity as Performance

In The Queen of Fives, identity is constructed, not inherited, and Quinn Le Blanc embodies this truth with merciless clarity. Her journey is driven by deliberate self-reinvention, not just for survival but for dominance.

From her assumed persona of Miss Quinta White to her careful orchestration of every detail—from gestures to accent to reputation—identity is treated as something malleable, transactional, and strategic. The distinction between who Quinn is and who she pretends to be erodes the longer she lives within her fabrications.

Yet, the novel resists simplifying this into a mere con. Quinn’s assumed identities are not just lies; they are armor.

In a society where legitimacy and class are gatekept by bloodlines and inheritance, she weaponizes performance as access. This theme becomes more complex when viewed through the lens of the other characters: Max, with his hidden romantic inclinations, performs emotional detachment to protect his status; Tor must present herself as the rational spinster-savior of the estate; and Lady Kendal buries her criminal past beneath the decorum of aristocracy.

The theme suggests that all social interaction, particularly among the powerful, is a kind of con—only the stakes differ. Identity becomes something constantly negotiated, often under duress, and always under observation.

Ultimately, Quinn’s final act of shedding all disguises is less about truth and more about authorship—choosing for herself what face to wear when no one is watching, and deciding that freedom lies not in assuming a new mask, but in no longer needing one.

Class Warfare and Social Manipulation

The plot of The Queen of Fives unfolds within the rigid hierarchies of Victorian England, a society obsessed with decorum and lineage. Quinn’s elaborate con relies on those very hierarchies to function: she must exploit the elite’s craving for wealth, beauty, and legacy while highlighting their blind spots.

The upper class is portrayed not as refined but as hollowed out—financially bankrupt yet desperately clinging to social status. Max’s need to marry for money, Tor’s desperate defense of her financial independence, and Lady Kendal’s obsessive control of image all underscore the brittleness of their supposed superiority.

In contrast, the Château—a criminal enterprise led by women—operates with its own brutal meritocracy. Intelligence, ambition, and strategy replace bloodlines and titles as the metrics of worth.

Yet even within this world, manipulation is currency. Class warfare isn’t fought through revolution here, but through deception.

The ruling class is neither noble nor wise; they are fallible and vulnerable to spectacle, which Quinn exploits masterfully. Her infiltration into Buckingham Palace is less a feat of disguise and more a critique of how superficial the upper class can be.

The fact that a fictional heiress gains immediate entry to the social elite exposes how deeply entrenched, yet absurdly fragile, class boundaries truly are. This theme reveals how power structures survive on mutual pretense—and how they can be upended not by confrontation, but by playing the game better than those who invented it.

Female Agency and Strategic Sisterhood

Though the narrative is riddled with betrayal and rivalry, The Queen of Fives centers on the various forms of female power—cooperative, competitive, strategic, and sometimes subversive. Quinn is the clearest embodiment of female agency, using intellect, deception, and performance to disrupt patriarchal systems.

But the novel doesn’t stop at glorifying her. Mrs.

Airlie, Tor, Lady Kendal, and even the rival queen from Quinn’s past represent different models of womanhood, each adapted to a specific structure of survival. Mrs.

Airlie navigates her power as a mentor through negotiation and contracts, insisting on boundaries even within criminality. Tor operates within a legal framework, seeking control over her finances and property through legitimate means.

Lady Kendal, however, reveals the darkest iteration of this theme—weaponizing motherhood, class, and sentiment to control not just outcomes but people. These women are not united by sisterhood in the traditional sense, but by the shared understanding that power is rarely granted and must often be taken.

The novel avoids sentimentality; cooperation among women is just as likely to be a mask for domination. However, it also allows for complex alliances, like the temporary trust between Quinn and Mrs.

Airlie or the unspoken camaraderie between Quinn and Tor at the end. The theme highlights the multifaceted nature of female strength—not as inherently moral or nurturing, but as adaptable, calculating, and deeply attuned to the rules of both the drawing room and the street.

Legacy, Inheritance, and the Haunting of the Past

The question of legacy in The Queen of Fives haunts every corner of the narrative. Whether it is the inheritance of estates, the continuation of noble bloodlines, or the shadow of former identities, characters are burdened by what they have been given—or what they have escaped.

Quinn inherits not wealth but skill, taught by a now-vanished mother who herself belonged to the underworld of confidence games. Her legacy is both a gift and a shackle: it empowers her but also places her within a dangerous tradition that others are vying to control or resurrect.

Max’s emotional secrecy and eventual proposal for a loveless alliance suggest that personal legacy must often be sacrificed for the sake of family name and estate. Tor’s financial paranoia stems not only from misogynistic structures but also from her awareness that women are often written out of legacy through legal technicalities.

Lady Kendal’s arc is perhaps the most emblematic of this theme. Her dual identity as both noblewoman and former grifter points to how legacy is as much constructed as it is inherited.

Her vendetta is rooted in past betrayals, and her vengeance becomes an attempt to rewrite the legacy denied to her. When Kendal House implodes—literally and metaphorically—it symbolizes the collapse of inherited structures when built on falsehoods.

In the end, Quinn’s decision to walk away from the Château and the Kendal title signals her rejection of inherited roles altogether, choosing instead a self-authored future unbound by blood, tradition, or society’s expectations.

Surveillance, Paranoia, and the Architecture of Control

Throughout The Queen of Fives, characters operate under constant surveillance—both literal and symbolic. Whether it’s Quinn’s awareness of being followed by mysterious figures, Max’s concealment of his emotional life, or Tor’s feeling of being watched and manipulated within her own home, the novel constructs a world where visibility is both a weapon and a vulnerability.

The aristocracy’s social rituals—balls, engagements, public appearances—are choreographed performances meant to control perception. Yet within these performances lies deep anxiety.

Quinn’s greatest skill is her manipulation of being seen: she understands exactly what the public wants and feeds it to them, from a staged assassination save to a waltz of courtly allure. But as the con thickens, she herself becomes a target.

Her every move is scrutinized not just by the Kendals but also by rival factions within the Château. This sense of omnipresent watchfulness mirrors real societal mechanisms where women, especially ambitious ones, are endlessly monitored and judged.

The Château’s Rulebook codifies this architecture of control: behavior, targets, alliances—all subject to constant evaluation. Even privacy becomes performative.

The physical spaces reflect this theme as well—Tor’s locked suite, the hidden attic filled with doll bombs, the drawing rooms where negotiations are staged—these are all arenas of control masquerading as domesticity. In the end, Quinn’s break from these layers of observation—rejecting both the château’s discipline and the public eye of high society—serves as a liberation not from danger, but from the gaze itself.

Her freedom is defined not by invisibility, but by no longer caring who watches.