The Red Letter Summary, Characters and Themes | Daniel G. Miller

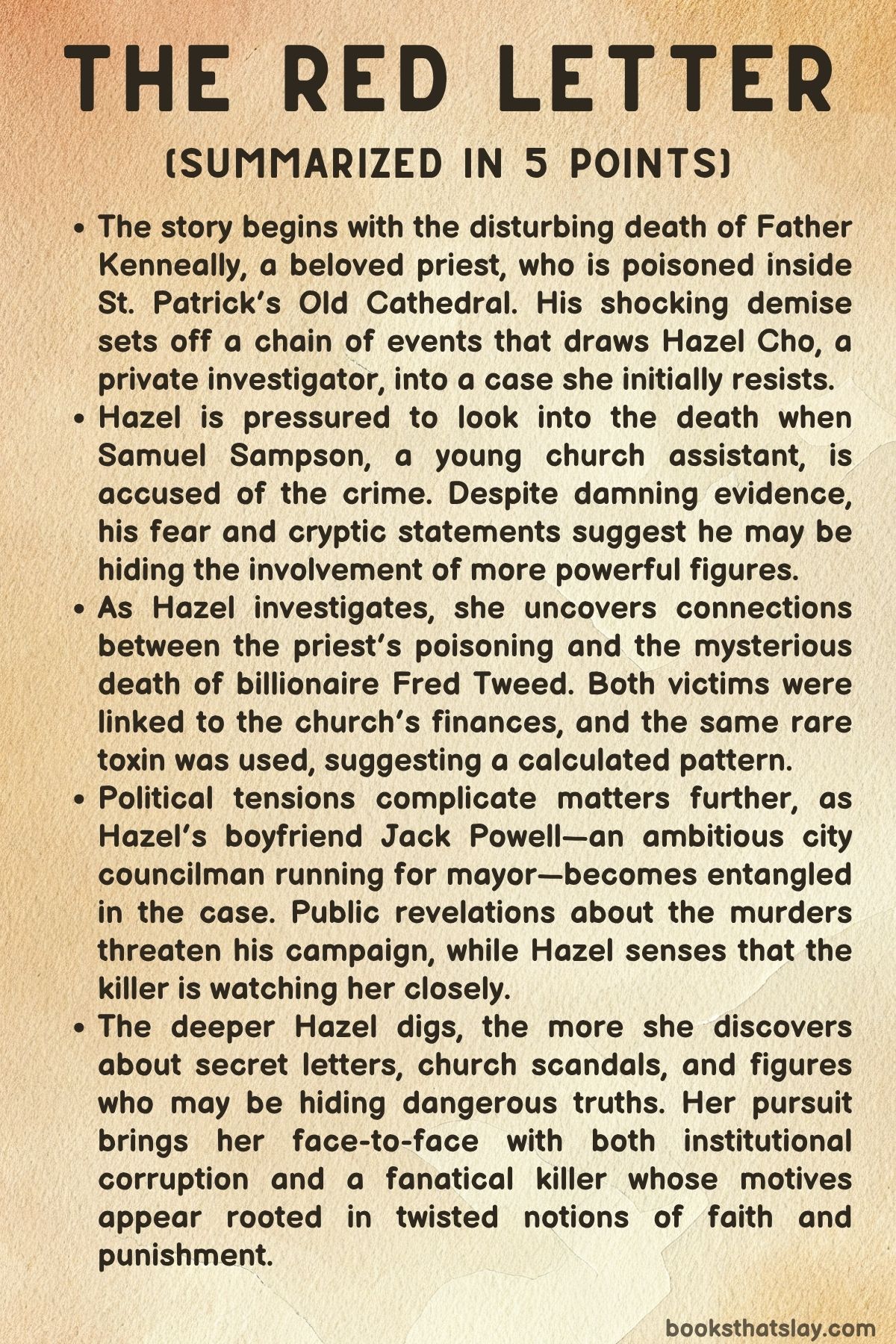

The Red Letter by Daniel G. Miller is a chilling mystery that blends crime, faith, and obsession.

At its heart is Hazel Cho, a private investigator pulled back into a world she desperately tried to leave behind. When a beloved priest dies under strange circumstances, and a teenage boy is accused of the murder, Hazel is forced to confront not only the shadowy figure of a serial killer but also her own past traumas. The story unravels across New York, mixing church politics, poisoned victims, and fanatical zealotry, while Hazel struggles to distinguish truth from deception. Miller delivers a tense narrative about justice, corruption, and the haunting cost of secrets. It’s the 2nd book in The Orphanage By The Lake series by the author.

Summary

The story opens with a disturbing video of Father Kenneally, a kind and respected priest, suddenly collapsing in his cathedral. His death, later confirmed to be caused by tetrodotoxin poisoning, shakes the community.

Hazel Cho, a private investigator, is asked by attorney Shavali Patel to investigate the case and clear Samuel Sampson, an eighteen-year-old church worker accused of the crime. Though Hazel initially refuses, citing her trauma and reluctance to return to dangerous work, the unusual method of murder and political pressure from her boyfriend Jack Powell—a rising city councilman running for mayor—draw her back in.

Hazel soon notices eerie connections. Another recent death, billionaire Fred Tweed, was also due to tetrodotoxin, supposedly from tainted sushi.

A chilling voice narrates the killings as holy punishment, hinting at the mindset of the murderer. Meanwhile, Jack’s campaign suffers when his opponent exposes the “Red-Letter Killer” during a debate, making Hazel’s investigation even more urgent.

Hazel herself begins to feel stalked, followed at night by a masked figure whistling “Danny Boy.

As Hazel digs deeper, she learns about ominous letters sent to the victims—sealed with wax, stamped with religious images, and containing biblical verses typed in red. Samuel Sampson is accused because of fingerprints on one such letter, though he denies involvement and hints at hidden truths about the church.

His cryptic warnings push Hazel to question the official narrative. Visiting Old St.

Patrick’s Cathedral, Hazel encounters Sister Teresa, whose cold and obstructive behavior raises suspicion. She and her team also uncover that the Archdiocese is entangled in scandal, having lost a massive lawsuit to victims of abuse, which may have provided motive for silencing key figures like Father Kenneally.

Hazel meets Archbishop Dinwiddie, who at first cooperates but quickly grows defensive. He dismisses any suggestion of wider corruption, but while speaking with Hazel, he collapses and dies of poisoning, another victim of the Red-Letter Killer.

Now under suspicion herself, Hazel is forced to move carefully while continuing the investigation. Linking the method of replacing daily medication with poisoned pills, she realizes the killer must have access to pharmaceuticals.

This leads her to suspect Sandy Godo, Jack’s political rival with a pharmaceutical background. Yet further digging into Fred Tweed’s widow reveals that Tweed himself had ties to church finances, deepening the web of motives.

Tragedy strikes when Jack is killed, leaving Hazel devastated. At his funeral, surrounded by friends, foes, and political players, she notices odd behavior from Shavali, who had secretly met with some of the victims.

Although Shavali denies direct involvement, Hazel’s trust weakens. Then, new evidence points to Sister Teresa’s past at a convent in Wappingers Falls.

Hazel drives there, where she uncovers Teresa’s obsessive, threatening letters and her background in chemistry experiments. To Hazel’s shock, the records reveal a disturbing photograph—Mary, her loyal assistant, once lived under the identity of Sister Teresa.

The revelation rocks Hazel: Mary might be the killer she has been searching for.

Hazel breaks into Mary’s apartment, located above a funeral home, and discovers a hidden laboratory filled with pill-making equipment, puffer fish, and dissected animals used in poison experiments. The evidence is undeniable.

But before she can escape, Mary catches her and knocks her unconscious. Hazel awakens strapped inside a cremation casket as Mary, fully revealed as the Red-Letter Killer, prepares to burn her alive.

Using her concealed weapon, Hazel manages to wound Mary and escape at the last moment. Police arrive, and Mary is arrested, unrepentant and fanatical to the end.

In the aftermath, Hazel is left grappling with grief over Jack’s death and betrayal by someone she trusted. Yet life slowly resumes.

Mary faces trial, her husband is implicated, and political power shifts as Sandy Godo wins the mayoral race. Hazel finds solace in family gatherings and in the support of friends like Kenny, Momo, and even Shavali, who remain by her side.

In one final, tender moment, Hazel’s mother places an extra chair at the table for Jack, affirming his place in their hearts. Though haunted, Hazel accepts that while loss cannot be undone, love and memory endure.

Characters

Hazel Cho

Hazel Cho is the central figure of The Red Letter, a private investigator with an unyielding sense of duty, yet someone who is constantly weighed down by past traumas. At first, she resists becoming involved in Father Kenneally’s murder case, fearing the emotional toll and professional entanglements it would bring.

However, her deep-rooted empathy and sharp instinct for uncovering truth slowly push her into the center of the investigation. Hazel is portrayed as both vulnerable and resilient: she suffers vivid nightmares of her past tormentor Andrew Dupont, which blur the line between memory and hallucination, but she never allows fear to fully paralyze her.

Her relationship with Jack Powell shows her longing for stability and love, yet also reveals how easily external manipulation—such as Shavali and Jack’s political pressures—can exploit her loyalties. Hazel’s arc demonstrates her evolution from a reluctant observer into a fearless pursuer of justice, confronting both external enemies and her own psychological scars.

Father Kenneally

Father Kenneally’s death sets the entire narrative in motion. Though he appears only briefly, his presence lingers throughout the story as both a victim and a symbolic figure.

He is introduced as kind, joyful, and beloved by his community, but suspicion around his personal and institutional ties clouds this image. Samuel Sampson’s cryptic comment that “Father K.

wasn’t such a good guy” raises the possibility that Kenneally was more complex than the saintly figure others describe. His poisoning becomes the first act of a ritualistic pattern of murders, transforming him from a respected priest into a pawn in the killer’s larger crusade.

In this way, Kenneally embodies both the vulnerability of innocence and the murkiness of hidden sins within powerful institutions.

Mary

Mary is one of the most pivotal and complex characters in the novel, initially presented as Hazel’s loyal assistant but ultimately revealed as the Red-Letter Killer. Her quiet, supportive demeanor makes her indispensable to Hazel, which only deepens the betrayal when her true identity comes to light.

Mary’s double life—devoted helper on one side, cold-blooded murderer on the other—captures the novel’s theme of duality and deception. Her obsession with sin, judgment, and purification manifests in her chemistry experiments and cruel killings, which she cloaks in the language of divine justice.

The discovery of her hidden laboratory filled with toxins, puffer fish, and dissected animals crystallizes her fanatical nature. Mary’s betrayal not only shatters Hazel’s trust but also symbolizes how corruption and violence can thrive even in the most familiar and intimate spaces.

Jack Powell

Jack Powell, Hazel’s boyfriend and a rising political figure, embodies ambition, charisma, and ultimately tragedy. His relationship with Hazel humanizes him, offering moments of warmth and intimacy, but his career as a city councilman running for mayor constantly entangles him in ethical compromises.

Jack’s reliance on Hazel’s involvement in the case highlights both his dependence on her judgment and his willingness to manipulate her for political gain. When his rival Sandy Godo exposes his ties to the Red-Letter case and questions his integrity, Jack becomes increasingly vulnerable.

His sudden death transforms him from an active participant in the political intrigue to a symbol of loss and betrayal in Hazel’s life. For Hazel, Jack’s memory becomes both a source of pain and a reminder of love that persists even after death.

Shavali Patel

Shavali Patel is an ambitious attorney whose sharp intellect and manipulative tendencies make her both ally and adversary. She initially recruits Hazel into the investigation under the guise of defending Samuel Sampson, but her hidden agenda—securing political favors for a judgeship—casts suspicion on her motives.

Despite her questionable ethics, Shavali is portrayed as resourceful and deeply committed to her own advancement, willing to exploit personal and professional relationships alike. Hazel’s strained trust in her reflects the novel’s recurring theme of betrayal and hidden intentions.

Shavali’s dual role as both legal advocate and political player ensures her constant presence at the intersection of justice and corruption.

Samuel Sampson

Samuel Sampson, the young man accused of murdering Father Kenneally, represents vulnerability, systemic bias, and hidden knowledge. At eighteen, he is caught between defiance and fear, projecting bravado while clearly overwhelmed by the gravity of his situation.

His refusal to disclose the contents of the envelope he delivered to Kenneally adds layers of mystery, suggesting he knows more than he reveals. His cryptic statement that “Father K.

wasn’t such a good guy” hints at deeper corruption within the church, yet his inability—or unwillingness—to explain himself fully makes him appear both suspicious and sympathetic. Samuel becomes less a suspect and more a mirror reflecting the institutional injustices and prejudices of the legal system, particularly in the hands of Detective Marcos, whose biases against him are evident.

Detective Marcos

Detective Marcos is a figure of antagonism, representing institutional prejudice and the dangers of narrow-minded policing. He quickly assumes Samuel’s guilt and resists Hazel’s challenges, embodying the systemic failures that can distort justice.

His arrogance and hostility serve as a foil to Hazel’s persistence and open-mindedness, reinforcing the novel’s critique of law enforcement’s tendency to prioritize convenient suspects over thorough investigations. Though he does not emerge as a central villain, his presence underscores how prejudice and incompetence can enable greater evils to flourish unnoticed.

Archbishop Milton Dinwiddie

Archbishop Dinwiddie represents the higher authority of the church, cloaked in charm and spiritual gravitas but riddled with secrecy. His insistence on Samuel’s guilt, coupled with his evasive responses about the church’s financial scandals, suggest complicity or at least willful blindness to deeper corruption.

His sudden death by poisoning mirrors that of Father Kenneally and Frederick Tweed, making him another pawn in the Red-Letter Killer’s campaign of judgment. His downfall underscores the vulnerability of even the most powerful figures when confronted with fanaticism and truth.

Sister Teresa

Sister Teresa is one of the most unsettling characters, her cold demeanor and fascination with the catacombs creating an atmosphere of menace. Her obstructive behavior during Hazel’s investigation raises immediate suspicion, and her connection to the convent where disturbing letters were discovered deepens the aura of fanaticism surrounding her.

While not the killer herself, her writings and obsessions foreshadow the psychology that drives Mary, linking the institutional church to the roots of the Red-Letter killings. She stands as a symbolic bridge between piety and obsession, between faith and fanatic cruelty.

Themes

Corruption and Institutional Secrecy

The narrative of The Red Letter consistently highlights the tension between faith-based institutions and the hidden corruption that festers beneath their surface. Father Kenneally’s death serves as the catalyst, but the surrounding investigation reveals systemic patterns of concealment.

The Archdiocese, embroiled in multimillion-dollar abuse settlements, provides a backdrop where the institution prioritizes self-preservation over truth or justice. Figures such as Sister Teresa and Archbishop Dinwiddie embody this secrecy, using their authority to deflect suspicion, deny transparency, and preserve the image of the Church even in the face of undeniable scandal.

This theme expands beyond the church walls, as the narrative demonstrates how wealth, political influence, and religious authority intersect to obscure accountability. The red letters themselves symbolize institutional guilt transcribed into personal threats, suggesting that the killer’s methods are both punishment and revelation.

The exploration of secrecy underscores how power structures protect their own, even at the expense of justice, creating an atmosphere where truth must be wrestled from deception and manipulation.

Justice and the Ambiguity of Innocence

At the heart of the novel lies the trial of Samuel Sampson, a teenager accused of murdering Father Kenneally. His situation reflects the fraught nature of justice when weighed against circumstantial evidence, systemic bias, and political expediency.

His fingerprints on the letter, his visible resentment toward his employer, and his vulnerability as a young Black man in a white-dominated institution combine to make him an easy target for both police and public suspicion. Yet Hazel’s investigation illustrates that guilt cannot be measured by appearances alone.

The ambiguity of innocence in the novel extends to nearly every character, with allies and adversaries alike revealing hidden motives or compromised positions. Even Hazel herself grapples with questions of whether her choices are fueled by pursuit of truth or by personal attachments.

This theme emphasizes the precarious balance between legal justice and moral justice, asking the reader to consider who truly benefits when institutions and politics determine guilt more than evidence does.

Trauma and Psychological Haunting

Hazel’s personal journey is deeply marked by trauma, which threads through her nightmares, her visions of Andrew Dupont, and her unease in moments of silence. The recurring presence of Andrew—even though dead—illustrates how past violence does not end with the physical act but continues to echo in the psyche.

Her inability to fully rest, coupled with the vivid imagery of being hunted or suffocated, shows how trauma transforms reality into a space of constant suspicion and dread. This psychological haunting directly influences her decisions in the investigation, often pulling her away from clear logic into moments of fear or mistrust.

It also complicates her relationships, particularly with Jack, whose warmth cannot shield her from the shadows of her past. Through Hazel, the novel examines how survivors of violence must contend not only with external threats but also with the internalized fear and memories that linger long after.

The theme builds an atmosphere of unease, reminding the reader that danger in this world is as much psychological as it is physical.

Faith, Fanaticism, and the Distortion of Belief

Religious imagery permeates the killings, most notably through the letters inscribed with biblical verses and grotesque depictions of hell. The killer frames their actions as divine justice, using poison as a tool of holy punishment.

This perversion of faith demonstrates how belief systems can be twisted into justification for cruelty. The Church, intended to be a sanctuary of compassion and morality, becomes both the hunting ground and the shield for fanaticism.

Characters such as Sister Teresa epitomize this distortion, embodying an obsession with sin and judgment that outweighs any sense of mercy. The theme resonates through the victims as well, who, despite being men of religious stature, are implicated in financial misconduct and systemic silence.

This contradiction—between the ideals of faith and the reality of its misuse—creates a chilling commentary on how religion can be weaponized. The narrative forces the reader to question whether faith in human institutions can ever be separated from the fanaticism that thrives when accountability is absent.

Love, Loss, and the Fragility of Relationships

The relationship between Hazel and Jack provides a counterpoint to the violence and corruption dominating the novel. Their intimacy offers her fleeting moments of safety, warmth, and stability, even as his political ambitions entangle her in the very case she seeks to avoid.

His sudden death marks a profound rupture, forcing Hazel to confront the fragility of love in a world poisoned by betrayal and obsession. Jack’s funeral not only crystallizes Hazel’s grief but also deepens her mistrust of those around her, including Shavali and Mary, who reveal ulterior motives.

The fragility of relationships is further emphasized in Hazel’s professional partnerships, where trust is continuously tested and fractured. Even moments of familial love, like her mother keeping a chair for Jack at Sunday dinner, reveal how love lingers as memory even when life has ended.

This theme underscores the duality of human connection—it is both Hazel’s greatest source of strength and her deepest vulnerability, shaping the emotional resonance of the novel’s conclusion.

Obsession with Control and Power

The Red-Letter Killer embodies an obsession with control, demonstrated in their precise methods of poisoning and the theatricality of their letters. The act of replacing daily medications with poisoned substitutes speaks to a desire not just to kill but to manipulate the intimate routines of victims.

This control extends beyond physical harm, as the letters instill fear and unsettle entire institutions. Mary’s eventual revelation as the killer underscores how obsession corrodes identity, turning her from a trusted assistant into a fanatic consumed by a distorted mission.

Political figures such as Jack and Sandy mirror this pursuit of control in their own domains, using the case as leverage to gain or maintain power. This theme highlights how obsession, whether rooted in fanaticism, politics, or personal ambition, reduces people to pawns in larger schemes.

The narrative suggests that the quest for control, once unleashed, becomes destructive not only for the victims but also for the perpetrators who lose themselves in the process.