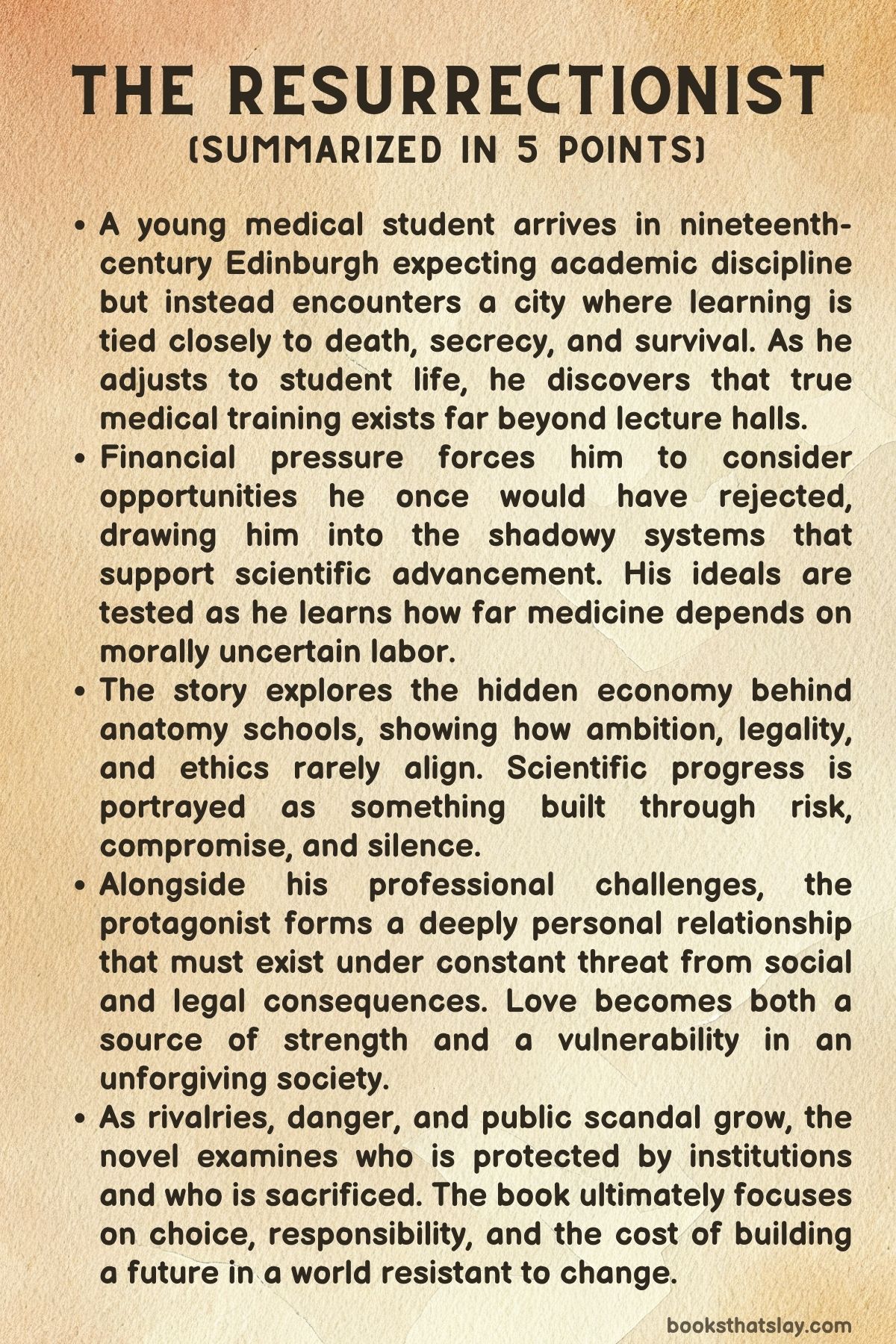

The Resurrectionist Summary, Characters and Themes

The Resurrectionist by A. Rae Dunlap is a historical novel set in early nineteenth-century Edinburgh, a city at the forefront of medical discovery and moral contradiction.

The story follows a young man who arrives hoping for academic rigor and personal independence, only to encounter a world where scientific ambition depends on secrecy, crime, and uneasy compromise. Through medicine, illegal anatomy, and forbidden love, the novel examines how knowledge is built, who pays its price, and what it means to choose one’s own life when society offers no safe path. Darkly intelligent and grounded in real historical practices, the book explores growth through risk and consequence.

Summary

James Willoughby arrives in Edinburgh in early November to begin his medical education, expecting something closer to the orderly world he left behind at Oxford. Instead, he is met with freezing rain, filthy streets, and a city shaped by death as much as learning. He takes a room at the Hope & Anchor Inn, a rough lodging house overlooking Greyfriars kirkyard.

His first night is marked by embarrassment when he struggles to haul his heavy trunk upstairs and nearly injures another guest, Charlie, who quickly becomes his guide to Edinburgh’s student culture.

Charlie introduces James to a small group of medical students who drink, joke, and treat death with unsettling casualness. Among them is Hamish, who casually produces a severed human ear from his pocket, claiming it came from his work at a private anatomy school.

James is disturbed but determined not to appear provincial. He soon learns that Edinburgh’s real medical training happens outside the university, in private surgical schools that rely on hands-on dissection rather than distant lectures.

Curious and ambitious, James attends an open demonstration at the anatomy school run by Dr. Louis Malstrom. During the session, Malstrom unexpectedly calls James forward and has him assist with a detailed dissection. James performs well, impressing both Malstrom and himself.

For the first time, he feels certain he belongs in medicine. That certainty collapses when he learns the tuition cost. His family fortune is gone following his father’s death, and he cannot afford to enroll.

Desperate for a solution, James approaches Malstrom’s assistant, Aneurin MacKinnon, asking about working in exchange for reduced fees.

Aneurin initially refuses but changes his mind after learning James’s room overlooks the kirkyard. He offers James a strange arrangement: James will act as a lookout at night, watching for the sexton while Aneurin monitors suspicious activity in the graveyard. James agrees, believing he is helping prevent crime.

The truth reveals itself quickly. One night, stones strike James’s window and Aneurin appears below, evading capture. James helps him climb into the room, only to learn Aneurin is not stopping grave robbers but supplying bodies to the anatomy school himself. Cadavers are scarce and illegal to obtain, yet essential for medical study. Aneurin argues that his work serves science and treats the dead with care.

James is horrified but trapped by his ambition and poverty. When Aneurin admits a stolen body is hidden beneath the window and proposes bringing it into James’s room temporarily, offering payment in return, James reluctantly agrees.

Together they haul the corpse into the room using ropes and beams, narrowly avoiding discovery. The body is hidden inside James’s trunk and smuggled at dawn to Malstrom’s school.

At the school, James wanders into a private laboratory filled with preserved organs and dismembered bodies. Overwhelmed, he confronts Aneurin and storms out, vowing to quit. That resolve ends when a letter arrives from his sister, Edith, announcing that his allowance is cut off and he is expected to abandon medicine for a merchant’s apprenticeship.

With no money and nowhere else to go, James returns to Aneurin and asks to join the resurrection work fully.

Aneurin challenges James’s moral objections, explaining that their work advances surgery, anatomy, and treatment for countless patients. He frames resurrection as giving bodies a second purpose. James accepts this reasoning and begins working as a digger. His first grave-robbing job is harrowing. He learns how to extract a body while leaving the grave undisturbed and witnesses the brutal practicality of the trade, including decapitation when metal collars prevent removal.

As James settles into this hidden life, he grows closer to Aneurin, known as Nye, and their partnership turns romantic. James struggles to balance his public role as a respectable student with his secret labor and relationship. When Nye suddenly withdraws for weeks, James’s distraction threatens his studies. Nye later explains that rival resurrection crews from London have entered Edinburgh, backed by the powerful Dr. Robert Knox, and violence is increasing. People connected to the trade are disappearing.

To gather information, James agrees to work briefly for Knox’s suppliers, Burke and Hare, posing as a transporter. Their behavior unsettles him, but he continues. Meanwhile, James’s sister Edith arrives unexpectedly, demanding he return to London and marry for money. James lies about his work and introduces Nye as a colleague. Edith remains suspicious and later discovers James and Nye together, condemning the relationship and threatening exposure. James refuses to submit, accepting estrangement from his family.

The danger escalates when James and Nye deliver a tea chest from Burke and Hare to Knox’s assistant and discover it contains the body of Mary Paterson, a woman they knew. Nye reacts with fury, and further investigation reveals that Burke and Hare are not robbing graves but murdering victims. Nye gathers scientific evidence showing death by suffocation and presents it to the police, who refuse to act.

Determined to stop the killings, the group devises a trap using James’s student friends as bait. The plan goes wrong when Burke and Hare grow suspicious and trap James and Nye inside the boarding house. Violence erupts, and Nye sets the building on fire to create a distraction. The two escape through the roof, narrowly avoiding death. Police arrive, find a hidden corpse, and arrest Burke and Hare.

At trial, Hare is granted immunity, and Burke is executed. Knox avoids punishment but flees the city. The victims receive little justice, and Nye is bitter that his evidence is ignored. As summer arrives, James is offered an apprenticeship at Malstrom’s school. Nye receives an offer to apply forensic science in London. Though wary, they decide to leave Edinburgh together and build a future on their own terms.

On the day of James’s exam, Nye gives him a repaired pocket watch containing a drawing and a reminder of everything they have survived. James reflects on how medicine, death, love, and choice have reshaped him. He sits his exam and steps into the next chapter of his life, no longer naive, but certain of who he is and who he stands beside.

Characters

James Willoughby

James Willoughby is the emotional and moral center of The Resurrectionist by A. Rae Dunlap, a young man whose journey is defined by transformation under pressure. Arriving in Edinburgh from an orderly, privileged Oxford background, he begins as earnest, idealistic, and socially awkward, struggling both with the physical harshness of the city and the moral shock of its medical culture. His financial ruin forces him into choices that steadily erode his former certainties, drawing him into grave-robbing, deception, and violence in the name of science and survival. Over time, James develops resilience, pragmatism, and a sharper ethical complexity, learning to live with contradiction rather than absolutes. His growth is not a loss of conscience but a redefinition of it, as he comes to accept responsibility for his choices, assert independence from his family, and openly commit to both his profession and his love for Nye, even at great personal risk.

Aneurin “Nye” MacKinnon

Aneurin MacKinnon, known as Nye, is both mentor and moral provocateur, embodying the uneasy marriage of science, art, and transgression. As a resurrectionist and anatomical assistant, he is intellectually driven and fiercely committed to medical progress, justifying ethically troubling acts through their potential benefit to humanity. Beneath his hardened pragmatism lies deep sensitivity, revealed through his anatomical drawings, his reverence for the dead, and his vulnerability regarding his past. Nye’s history of persecution for his sexuality shapes his guarded nature and his instinct for survival, while his relationship with James reveals his capacity for tenderness, loyalty, and emotional honesty. He represents a radical alternative to conventional morality, challenging James to reconsider where meaning, duty, and love truly reside.

Mary Paterson

Mary Paterson serves as a haunting symbol of the human cost underlying the medical and criminal systems of the time. In life, she is perceptive, socially agile, and active in gathering intelligence for resurrectionists, navigating dangerous spaces with intelligence and courage. In death, her body becomes a site of horror and moral reckoning, exposing the reality that Burke and Hare are murderers rather than mere body snatchers. Her transformation from participant to victim underscores the fragility of agency in a world that commodifies bodies, particularly those of women. Mary’s fate galvanizes Nye and James into action, giving a face to injustice and forcing them to confront the limits of scientific justification.

Hamish

Hamish initially appears as a swaggering, grotesquely casual medical student, fascinated by anatomical curiosities and aligned with Dr. Knox’s school. As the narrative unfolds, he is revealed to be far less powerful than he pretends, functioning largely as a cleaner and errand-runner within Knox’s hierarchy. His bluster masks insecurity and dependence, particularly his debt to higher powers in the resurrectionist network. Hamish represents the disposability of lower-ranking figures within exploitative systems, as well as the moral emptiness that comes from proximity to power without true agency. His eventual subjugation by Nye strips away his pretensions and exposes the fragile social ladders of Edinburgh’s medical underworld.

Charlie

Charlie functions as James’s first point of connection in Edinburgh, embodying camaraderie, adaptability, and youthful irreverence. His easy manner helps draw James out of his isolation and into the city’s social and professional networks. Though not deeply involved in resurrectionist work, Charlie’s willingness to assist in dangerous schemes reflects loyalty and trust, even when he does not fully grasp the stakes. He represents the ordinary student caught on the fringes of extraordinary events, a reminder of the life James might have led had circumstances not pushed him into darker territory.

Phillip

Phillip is a quieter but steady presence among James’s circle, defined by pragmatism and reliability. He participates in risky plans not out of ideological commitment but out of friendship and necessity, grounding the group with a sense of cautious realism. Phillip’s involvement highlights how easily ordinary individuals can be drawn into criminal or morally ambiguous acts through social bonds rather than personal ambition. His character underscores the collective nature of survival in Edinburgh’s medical world, where individual choices are often inseparable from group dynamics.

Luke

Luke appears briefly yet contributes to the early normalization of macabre curiosity that James must confront. His casual engagement with dissection culture reflects how desensitization operates within the medical community, especially among students eager to prove their fortitude. Luke serves less as an individual arc and more as a representation of how institutional environments shape behavior, reinforcing the idea that shock fades quickly when rewarded with belonging and advancement.

Dr. Louis Malstrom

Dr. Louis Malstrom embodies the progressive yet ethically ambiguous face of medical advancement. Charismatic, demanding, and intellectually formidable, he recognizes James’s talent immediately and nurtures it with calculated encouragement. Malstrom’s reliance on illicitly obtained bodies is framed as necessity rather than malice, positioning him as a figure who prioritizes outcomes over means. He represents the scientific establishment’s willingness to benefit from criminal acts while maintaining plausible deniability, benefiting from moral distance without ever fully confronting the human consequences of his work.

Dr. Robert Knox

Dr. Robert Knox stands as the novel’s most chilling representation of institutional corruption. Unlike Malstrom, Knox is driven less by education than by prestige, power, and competition. His complicity in Burke and Hare’s murders, coupled with his indifference to evidence and human suffering, marks him as morally bankrupt. Knox’s eventual escape from legal punishment highlights systemic injustice, revealing how authority and reputation shield those at the top while victims and intermediaries bear the cost. He functions as a critique of unchecked ambition within scientific and social hierarchies.

Burke

Burke is portrayed as overtly violent, volatile, and predatory, driven by greed and opportunism. He thrives on intimidation and control, escalating from exploitation to murder with alarming ease. His character exposes how poverty, alcoholism, and moral disengagement can combine into brutality when reinforced by profit and impunity. Burke’s eventual execution offers a rare moment of accountability, though it cannot undo the suffering he caused.

Hare

Hare contrasts with Burke through cowardice rather than cruelty, though he is no less culpable. He survives by betraying others, trading truth for immunity and self-preservation. Hare represents the moral emptiness of survival at any cost, embodying a justice system willing to exchange truth for convenience. His freedom after the trial reinforces the novel’s bleak view of legal compromise and selective morality.

Edith Willoughby

Edith Willoughby functions as both familial antagonist and catalyst for James’s emancipation. Practical, judgmental, and deeply invested in social respectability, she views James primarily as a means of restoring family fortune and honor. Her inability to comprehend his choices or his love for Nye reflects the rigid constraints of class, reputation, and heteronormativity. Paradoxically, her threats and condemnation ultimately free James from familial control, forcing him to choose authenticity over obligation and marking a decisive break from his former life.

Themes

Ambition, Survival, and Moral Compromise

From the moment James Willoughby arrives in Edinburgh in The Resurrectionist, his ambitions are framed not as abstract dreams but as urgent necessities tied to survival. His desire to become a skilled physician is constantly pressured by financial ruin, social displacement, and institutional barriers. Unlike the orderly academic world he expected, Edinburgh demands flexibility, endurance, and a willingness to accept uncomfortable truths. James’s choices are rarely framed as purely ethical or unethical; instead, they emerge from a space where ambition collides with scarcity. His decision to assist Aneurin in body-snatching is not driven by greed or cruelty but by the realization that conventional paths are closed to him. Medical knowledge, in this world, is not freely available to those without money, and ambition without resources quickly becomes desperation.

As James becomes more deeply involved in resurrection work, moral boundaries shift rather than disappear. He repeatedly attempts to justify his actions by aligning them with scientific progress, emphasizing respect for the dead and the potential benefits to the living. Yet the narrative never allows him full comfort in these justifications. His revulsion in Malstrom’s laboratory, his hesitation during his first dig, and his lingering unease after each success reveal an internal struggle that remains unresolved. Survival demands action, but conscience demands reckoning. What makes this theme compelling is that James is not corrupted all at once; instead, he learns how easily compromise becomes routine when one’s future depends on it. Ambition does not erase morality, but it reshapes it, forcing James to live with contradictions rather than clean resolutions.

Science, Progress, and Ethical Blindness

Medical progress in The Resurrectionist is portrayed as both transformative and deeply unsettling. The pursuit of anatomical knowledge is relentless, practical, and often indifferent to the human cost. Surgeons like Malstrom and Knox justify morally questionable practices by pointing to innovation, discovery, and the future of medicine. Their laboratories are spaces of learning but also of dehumanization, where bodies are reduced to resources and individuality is erased. James’s early excitement during his first dissection contrasts sharply with his later horror when he witnesses the full scope of experimentation. This contrast highlights how scientific authority can normalize acts that would otherwise be considered intolerable.

The novel questions whether progress can truly be separated from the means used to achieve it. Resurrectionists argue that they grant bodies a second purpose, framing their work as almost benevolent. However, the exposure of Burke and Hare’s murders reveals how easily ethical blindness can escalate when demand outweighs oversight. The medical establishment’s willingness to ignore evidence, silence whistleblowers, and protect reputations underscores a systemic failure rather than individual wrongdoing alone. Science, in this context, is not inherently cruel, but it becomes dangerous when detached from accountability. James and Nye’s frustration when their forensic evidence is dismissed reflects a broader critique: truth does not automatically triumph when it threatens powerful institutions. The theme ultimately suggests that progress without ethical responsibility risks becoming another form of violence.

Identity, Secrecy, and Chosen Lives

James’s journey is also one of identity formation shaped by secrecy. In Edinburgh, survival requires concealment: hidden corpses, false stories, and carefully managed appearances. James learns to separate who he is from who he appears to be, especially when interacting with his family. His relationship with Nye intensifies this division. Their bond exists in private spaces, shadowed by legal and social danger. Nye’s past, marked by persecution for his sexuality, reinforces the necessity of secrecy not as deception but as self-preservation.

This theme extends beyond personal relationships into professional life. James moves between university halls, taverns, graveyards, and anatomy labs, adopting different versions of himself in each. Over time, these divided identities stop feeling temporary and begin to define him. When Edith confronts him, her shock stems not only from his relationship but from the realization that James has chosen a life beyond her control. His refusal to return to London marks a turning point where secrecy no longer feels like shame but like ownership of his own path. Identity in The Resurrectionist is not inherited or granted; it is constructed through risk, loyalty, and choice, even when that choice carries consequences.

Power, Exploitation, and Institutional Failure

Power in The Resurrectionist operates quietly but decisively. Surgeons, magistrates, and wealthy patrons exert influence without direct involvement in violence, allowing others to absorb the risk. Dr. Knox’s ability to evade punishment despite clear moral responsibility exposes how authority shields itself. Those at the margins, including resurrectionists, the poor, and murder victims, bear the cost of a system that values results over justice. James’s growing awareness of this imbalance shapes his disillusionment more than any single act of brutality.

The police’s refusal to act on Nye’s evidence further reinforces the theme of institutional failure. Truth is presented, tested, and verified, yet dismissed because acknowledging it would disrupt existing power structures. Even Burke’s execution feels incomplete, as it addresses individual guilt while ignoring the network that enabled him. This failure leaves James and Nye with a sense that justice is selective and fragile. Their decision to leave Edinburgh does not signal defeat but recognition that reform from within is unlikely. The theme underscores that exploitation is sustained not by monsters alone but by systems designed to protect themselves, even when confronted with undeniable harm.