The Resurrectionist Summary, Characters and Themes

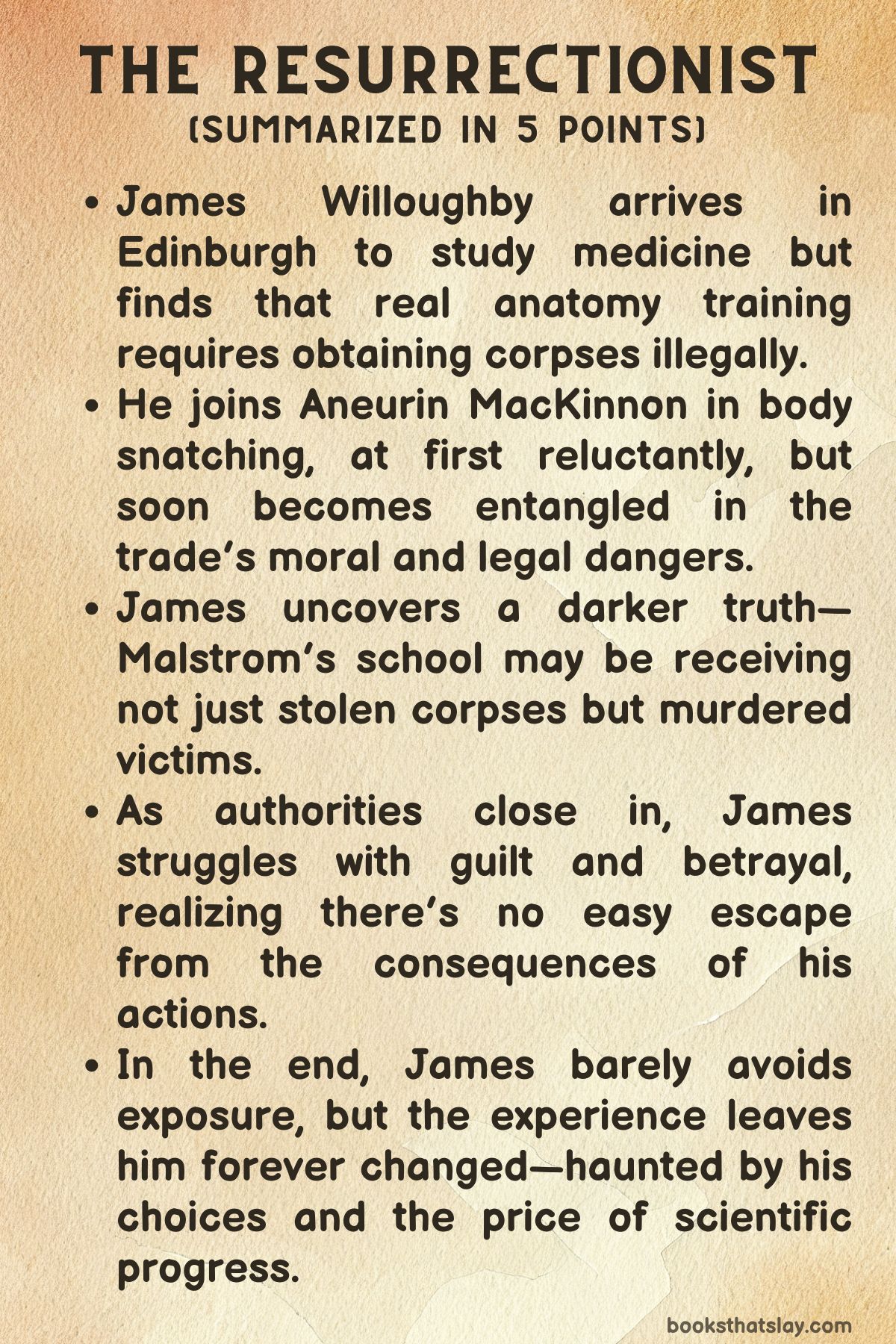

The Resurrectionist by A. Rae Dunlap is a darkly immersive historical novel set in 19th-century Edinburgh, a city where progress in medical science clashes with the harsh realities of class, law, and mortality. It follows James Willoughby, a genteel but naive young man, as he steps into the morally complex world of anatomical study.

Faced with financial hardship and personal awakening, James is drawn into a clandestine network of Resurrectionists—those who procure corpses for medical research—led by the enigmatic Nye MacKinnon. This book explores the price of knowledge, the burden of love, and the moral ambiguity of progress in a time when the dead fueled the future.

Summary

James Willoughby arrives in Edinburgh with refined manners and an Oxford education, but soon realizes he is unprepared for the city’s raw, visceral demands. The cold inn where he lodges becomes the unlikely setting for friendships with a lively group of medical students.

Among them is Hamish, who introduces James to the local culture of dark humor and gallows curiosity, typified when a severed human ear is casually produced at a pub. These early days steep James in the rowdy undercurrent of the city’s medical scene, far from the decorum he once knew.

James’s formal education begins at the prestigious but inaccessible Malstrom Surgical School, where he watches Dr. Malstrom perform a dissection.

Unexpectedly invited to assist, James impresses the crowd and himself, discovering a hunger for practical medicine. Unable to afford the tuition, he approaches Aneurin “Nye” MacKinnon, Malstrom’s assistant, for help.

Nye proposes a secretive arrangement: James will act as lookout during night watches at Greyfriars Kirkyard, under the pretense of catching grave robbers.

The truth unravels slowly. Nye is not there to prevent grave robbing but is entangled in something far more ambiguous.

After a dramatic night where Nye seeks James’s help under cover of darkness, James realizes he has been used. Nye, however, denies any direct involvement in grave desecration and invites James to hear his side over drinks.

Their evening at the Pig & Swindle reveals a shadowy subculture where cadavers are currency and reputations are built on questionable ethics. Nye’s background as a butcher’s son with natural surgical skills strikes a chord in James, who feels unmoored from the expectations of his class.

A tentative friendship and eventual romantic bond grow between them, forged through shared ambition and mutual alienation. But the deeper James goes into Edinburgh’s medical world, the more he sees its reliance on bodies no one wants to talk about.

The dissection rooms and lecture halls demand corpses, and supply is always short. Eventually, James aids Nye in transporting a corpse, a grim task marked by both revulsion and exhilaration.

It’s a moral tipping point. When he later discovers Nye’s secret lab filled with mutilated remains, his disgust overwhelms him.

But life intrudes. James’s family fortune collapses, tuition is no longer an option, and with nowhere else to go, he returns to Nye—this time asking to join the business.

Nye offers one last look at the lab, reframing its grotesque interior as a site of innovation and utility. Corpses, Nye explains, are being used to advance dental surgery, improve prosthetics for veterans, and even explore speech mechanics.

James, desperate and searching for purpose, chooses to see this world through Nye’s eyes. They dig together, and James passes the unspoken test of grit.

From outsider to participant, he is now part of a secret brotherhood that thrives in the city’s shadows.

Their bond deepens when Nye goes silent, and James’s world begins to unravel. His academic focus deteriorates as he obsesses over Nye’s disappearance.

When Nye finally returns, he reveals the rise of a rival syndicate, run by Dr. Knox and his hired killers.

James is torn between hurt and relief, but Nye’s affection remains, even if veiled in secrecy. In a charged reunion, Nye takes James to his chambers, an intimate space of anatomical artistry and private memory.

Their relationship solidifies—no longer just partners in crime but also in affection and emotional truth.

Amid rising tensions in the Resurrectionist underworld, James and Nye, with the help of their friend Mary Paterson, plan to infiltrate Knox’s organization through James’s former friend Hamish. Knox’s crew includes the chilling duo Burke and Hare, whose ruthlessness surpasses anything James has encountered.

Their plan—to masquerade as transporters—succeeds at first, but its emotional cost is high. When Mary disappears and is later revealed to be a victim, James and Nye are devastated.

The dissection table becomes a site of horror rather than learning, her body the evidence of unchecked cruelty.

Refusing to accept silence, Nye and James begin a covert investigation. Through biochemical analysis and trauma study, Nye proves that the victims were murdered—deliberately suffocated, their bodies sold as fresh specimens.

Yet when they present their findings, institutional apathy crushes them. The authorities refuse to act without catching Burke and Hare in the act.

Frustrated but not defeated, they set a trap using James’s classmates as bait.

The plan almost fails. Nye and James are captured, nearly killed, and saved only by Nye’s improvisation—a fire, a counterweight, and quick fingers.

Their daring escape finally draws enough attention. Burke is caught, tried, and hanged, but justice remains incomplete.

Hare is granted immunity, and Knox avoids punishment entirely. Nye’s groundbreaking forensic methods are ignored in favor of simpler testimony.

Despite this, a new path opens. Nye is offered a job with the national police, and James, disillusioned by both the elite world he came from and the underworld he entered, decides to go with him.

They choose each other and a future away from the dark alleys of Edinburgh. In the end, James receives a gift from Nye: his father’s pocket watch, refitted with an illustration of Nye’s eye—a token of love and memory.

As exams approach and the city fades behind them, James carries forward not only the knowledge he gained but the bond he forged in defiance of convention. The story closes not with vindication but with the quiet promise of purpose, truth, and resilience shared between two people who chose their own way forward.

Characters

James Willoughby

James Willoughby begins his journey in The Resurrectionist as a sheltered, idealistic student from Oxford who enters Edinburgh with a naïve belief in the noble pursuit of medicine. His genteel upbringing and initial detachment from the realities of dissection and death serve as the baseline from which his complex evolution unfolds.

James’s character is initially marked by internal conflict between his moral compass and the pragmatic, often ethically ambiguous world of Enlightenment-era medicine. His first foray into the underbelly of medical study is framed as a shocking but thrilling awakening—his encounter with the severed ear at the pub table and his impromptu participation in a dissection mark his initiation into this raw new world.

Over time, James transitions from mere observer to active participant. He becomes entangled not only in grave-robbing operations but also in a web of emotional and ethical contradictions.

His financial instability and hunger for intellectual fulfillment propel him into choices that he initially condemns. The discovery of a secret lab filled with mutilated corpses causes moral revulsion, but the dire collapse of his family’s fortune forces him to reconsider his place in the Resurrectionist trade.

His decision to join Aneurin’s operation fully is both a surrender to necessity and a declaration of newfound purpose. Through this transformation, James sheds his inherited sense of decorum, forging a new identity shaped by bodily truth, forbidden love, and a commitment to knowledge, even when it comes at the cost of personal innocence.

His arc is one of descent and rebirth, from privilege and detachment into the grim, beating heart of medical advancement.

Aneurin “Nye” MacKinnon

Aneurin MacKinnon, often referred to as Nye, is the enigmatic and magnetic figure who catalyzes James’s transformation in The Resurrectionist. With a past rooted in the blood and sinew of a butcher’s trade on the remote island of Iona, Nye carries a rugged, unpolished authenticity that contrasts starkly with James’s genteel background.

He is both a skilled anatomist and a philosophical provocateur, challenging the sanitized ideals of medicine with the visceral realities of body acquisition and experimentation. Despite his involvement in the morally dubious Resurrectionist trade, Nye is not a mere criminal; he views his work as a form of redemption for the dead and enlightenment for the living.

Nye’s complexity lies in his contradictions: he is tough yet tender, manipulative yet sincere, secretive yet emotionally vulnerable. His affection for James gradually reveals layers of his own trauma and desire—for connection, for understanding, and for legitimacy in a world that marginalizes people like him.

His secret chambers reflect his dual nature: a haven of macabre beauty and scientific precision. Nye’s forensic brilliance ultimately positions him as a pioneer, but one whose contributions are obscured by systemic prejudice and institutional corruption.

His love for James becomes not just a romantic subplot but a deeply human tether in a world of violence and decay. Through Nye, the novel interrogates the boundary between desecration and discovery, brutality and benevolence, offering a character who is as unsettling as he is essential.

Mary Paterson

Mary Paterson is a fiercely independent and loyal ally within the dangerous world of The Resurrectionist. As a close friend and informant to Nye and James, she bridges the shadowy gap between the Resurrectionist crews and the street-level realities of survival in Edinburgh.

Sharp, brave, and resourceful, Mary operates in a world dominated by men and violence, yet she carves out a space of her own through cunning and resilience. Her commitment to justice and camaraderie is most vividly displayed when she alerts the group to the rising threat posed by Knox and his brutal operatives.

Mary’s fate—being murdered and offered as a specimen—transforms her from a character of action into a tragic symbol of the system’s cruelty.

Her death catalyzes the emotional and investigative climax of the novel, especially for Nye and James, who mourn her not just as a friend but as a casualty of institutional greed and disregard for life. Mary embodies the forgotten, the used, and the sacrificed, yet her legacy fuels the characters’ resolve.

In life and death, she asserts the value of dignity and voice, even in a world that would reduce her to a cadaver on a table.

Edith Willoughby

Edith Willoughby, James’s sister, is the embodiment of societal pressure and familial obligation in The Resurrectionist. She represents the world James left behind—a world of decorum, class, and rigid expectations.

Her arrival in Edinburgh is a jarring intrusion into James’s self-fashioned reality. With her comes the weight of tradition: a marriage proposal from Violet Witherspoon and the financial security it promises.

Edith’s outrage at James’s choices—his profession, his poverty, and his romantic entanglement with Nye—serves as a microcosm of societal condemnation, particularly toward queer identity and moral transgression.

Yet Edith is not merely a villain; she is a product of her upbringing and a woman constrained by the very forces she seeks to enforce. Her anger stems from fear—for James’s reputation, for her family’s standing, for the fragility of the social order.

Her condemnation is harsh, but it reveals the depth of familial love warped by conventionality. Through Edith, the novel explores the painful intersection of personal authenticity and societal conformity, forcing James to assert his autonomy with painful finality.

Her role, while antagonistic, is essential in catalyzing James’s ultimate declaration of selfhood.

Dr. Malstrom

Dr. Malstrom, the French instructor at the surgical school, is a peripheral yet influential figure in The Resurrectionist, representing the allure of scientific advancement wrapped in charisma and ambition.

His surgical demonstrations captivate James early in the story, serving as the spark that ignites the young student’s obsession with anatomy and hands-on learning. Malstrom’s absence during key moments ironically facilitates Aneurin’s deeper involvement in James’s education, suggesting that the true mentorship lies elsewhere.

Nonetheless, Malstrom’s presence sets the tone for the novel’s interrogation of performance, power, and progress in the medical profession. He is both an idol and an abstraction, his brilliance unquestioned but his ethical boundaries conveniently vague.

Burke and Hare

Burke and Hare are the novel’s darkest figures—calculating murderers masquerading as suppliers in the medical cadaver trade. Their partnership with Knox and their role in Mary’s and Daft Jamie’s deaths expose the depraved extremes to which scientific ambition can sink when unchecked by ethics.

Cold and business-minded, they lack the philosophical justifications Nye clings to, serving instead as a chilling reminder that not all Resurrectionists act out of necessity or idealism. They represent the commodification of the human body taken to its most horrifying conclusion, making them the ultimate antagonists in James’s moral and emotional journey.

Their presence underscores the novel’s central tension between scientific necessity and the sanctity of life.

Themes

Moral Ambiguity and the Ethics of Scientific Progress

In The Resurrectionist, Rae Dunlap constructs a world in which medical advancement collides violently with conventional morality, forcing characters to operate within ethically gray zones. James Willoughby’s journey from idealistic Oxford scholar to clandestine Resurrectionist is shaped by the impossible demands of a society that simultaneously craves scientific progress and condemns the means by which it is achieved.

His initial revulsion toward body snatching—an act socially scorned though legally ambiguous—gives way to reluctant participation once he confronts the financial and practical impossibility of acquiring medical education otherwise. The legal system’s loophole, which treats body theft as a minor misdemeanor, speaks volumes about societal duplicity: the state refuses to acknowledge the medical necessity of cadavers while still depending on the illicit trade to supply schools with anatomical material.

James’s horror at Aneurin’s underground lab is rooted not in a rejection of knowledge, but in its presentation; only when Aneurin reframes the space as one of utility and healing does James reconcile the image of mutilated corpses with the nobility of medicine. The novel insists that advancement is never clean.

Dissection, surgery, and scientific rigor require human cost, and those who pursue these disciplines must learn to navigate a web of compromise. The deeper James is drawn into the Resurrectionist world, the more he understands that progress is built upon unseen sacrifices—often anonymous, often unacknowledged.

His transformation does not absolve the ethical conflicts; it simply recognizes that science’s demands do not wait for society’s consent.

Love, Secrecy, and Queer Resistance

James and Nye’s relationship is forged in a world that offers no language for their desire beyond secrecy and shame. Their bond is made more powerful by its defiance of convention—not only because they are two men in a deeply repressive society, but because their intimacy emerges from shared danger, intellectual kinship, and emotional refuge.

The romantic tension is compounded by fear: Nye’s evasiveness, James’s longing, and the threat of public exposure all coalesce into a love story defined by discretion and urgency. Their tender moments—stolen in anatomical workrooms, in Nye’s studio, or after a grave-digging operation—exist outside society’s gaze, as necessary acts of resistance against both external threat and internalized doubt.

Edith’s arrival and her disgust at their relationship serve as a brutal reminder of the stakes. Her proposal—marriage to a wealthy heiress—offers a path of respectability that would erase everything James has come to value.

His refusal is not just an act of rebellion but one of self-definition. This love story refuses to sentimentalize its conditions.

Instead, it presents secrecy not as shame but as strategy, and queerness not as deviation but as another form of survival and authenticity. Their final decision to leave Edinburgh together and seek new beginnings in London suggests not an escape, but a deliberate reorientation—a pursuit of life not within the margins but beyond them.

Class Disparity and Social Hypocrisy

The world of The Resurrectionist is rife with class distinctions that shape every facet of James’s identity, ambition, and belonging. Born into genteel privilege, James enters Edinburgh’s gritty underworld with an inherited sense of entitlement that quickly dissolves.

The comforts of Oxford, the prospects of arranged marriage, and his sister Edith’s expectations reflect a rigid social structure built to preserve wealth and reputation rather than knowledge or purpose. Aneurin, by contrast, is a butcher’s son whose surgical skill was learned through necessity, not luxury.

His refusal to romanticize anatomy, his facility with the knife, and his ability to survive in a system designed to exclude him all underscore a meritocracy that exists in the shadows. The dissonance between James’s origins and his chosen path becomes most visible when Edith offers him twenty thousand pounds and a prestigious marriage—an escape from struggle, but at the cost of his autonomy and his love for Nye.

His rejection of this offer marks the moment he steps outside the social order that once defined him. Meanwhile, the institutions of power—universities, constables, and medical boards—willingly benefit from the bodies supplied by the working class, yet refuse to acknowledge or protect the people involved in procurement.

Justice is not denied because of lack of evidence but because of class-based moral calculations. Burke and Hare, working-class murderers, are manipulated by Knox, a respectable surgeon who escapes censure.

In this world, class is not only a hierarchy of wealth, but of moral consequence.

Death, Utility, and the Body as Resource

A recurring motif throughout The Resurrectionist is the transformation of the human body from sacred vessel to scientific commodity. The narrative relentlessly pushes the reader to question where dignity ends and utility begins.

For James and his peers, the body is both a symbol and a tool—necessary for education, experimentation, and healing, but also a source of horror, desecration, and guilt. Aneurin’s reframing of the underground lab as a place of innovation rather than mutilation forces James to confront the uncomfortable truth that reverence and usefulness may not always align.

Cadavers are not simply dead—they are raw material from which new life-saving techniques are born. The choice to become a digger is, in this light, not purely transactional, but philosophical.

It is an embrace of a worldview that sees death as a continuation of purpose. Burke and Hare’s shift from snatching to murder reflects the perversion of this utility: when the body becomes valuable enough to kill for, the boundary between medicine and violence collapses.

Mary’s murder and eventual dissection exemplify this collapse. Her death, originally meant to further science, ends up being the very proof used to condemn its corruption.

By the novel’s end, the body is no longer merely the object of study—it becomes the battlefield upon which moral, legal, and emotional wars are fought. The final image of Nye’s anatomical drawings and the pocket watch bearing the Lover’s Eye reclaims the body once again, not for science or society, but for love, remembrance, and renewal.