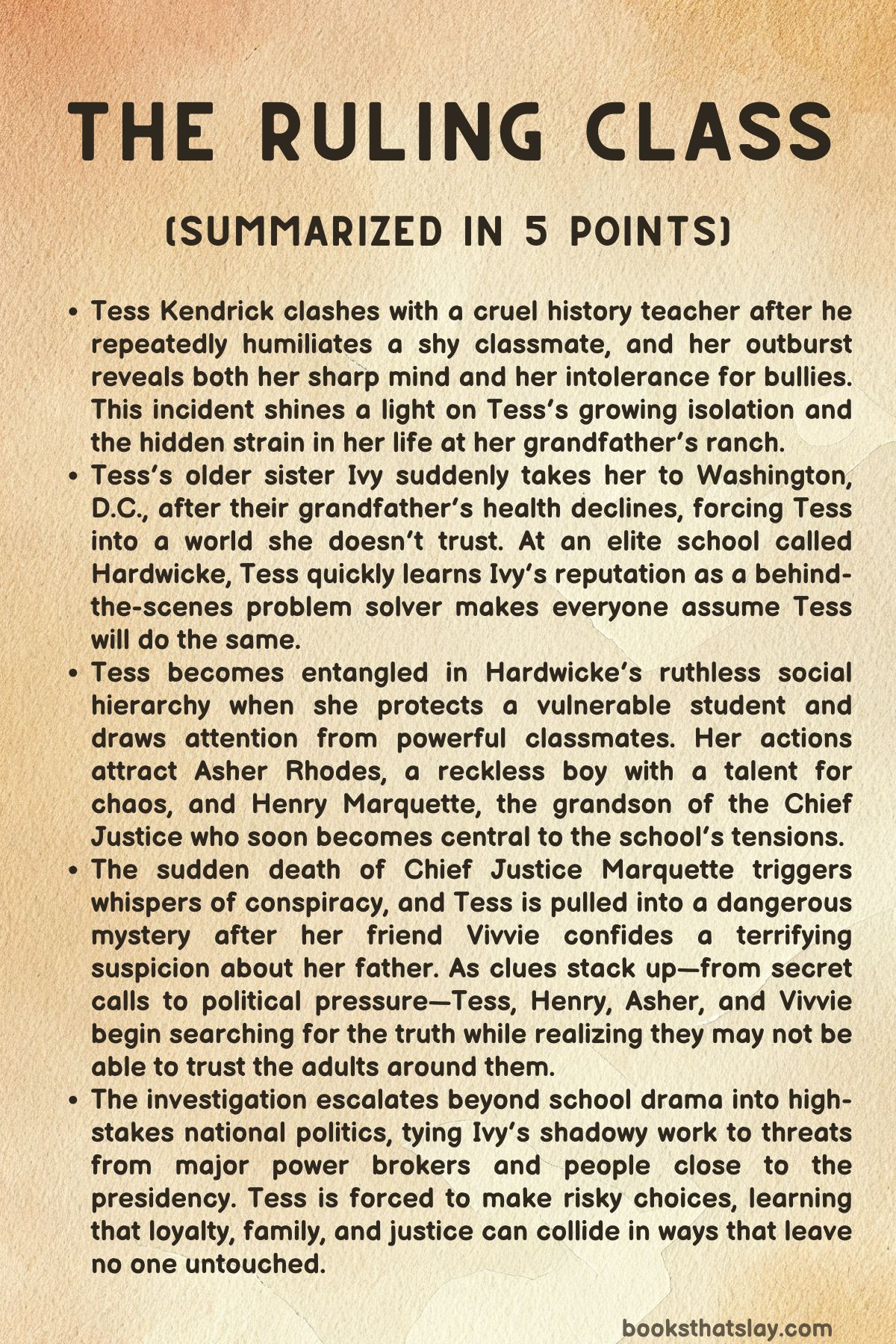

The Ruling Class Summary, Characters and Themes

The Ruling Class by Jennifer Lynn Barnes is a fast, razor-edged YA political thriller set inside the pressure-cooker world of Washington, D.C.

It centers on Tess Kendrick, a ranch-raised teen ripped from her quiet life and dropped into an elite academy for the children of the powerful after her guardian’s health collapses. Tess quickly discovers that her older sister Ivy is a legendary fixer for the nation’s most influential families. When the death of a Supreme Court justice sends shockwaves through the capital, Tess is drawn into a conspiracy that forces her to confront privilege, loyalty, and the ruthless logic of power.

Summary

Tess Kendrick has never been good at staying silent when someone is being mistreated. In her small-town history class, she finally snaps when Mr. Simpson humiliates Ryan Washburn, a shy student who is constantly singled out. Tess corrects Simpson’s sloppy lesson on the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of slavery, and when he tries to mock her with Shakespeare, she shoots back with another quote.

The triumph lasts about ten seconds before she’s sent to guidance. There, the counselor points out that her grades are slipping, she quit track, and she’s been skipping class. Tess bristles and redirects the conversation to Simpson’s bullying, thinking of abused horses on her grandfather’s ranch. She dares the counselor to call her grandfather, even though the idea knots her stomach.

A few days later, Tess is on the ranch trying to calm a traumatized horse when her estranged older sister Ivy appears without warning. Ivy hasn’t visited in three years—not since offering to take Tess to D.C. and then vanishing. Tess tries to avoid her, but Ivy pushes inside, explaining that the counselor called and she’s concerned. Tess panics, afraid Ivy has noticed what Tess has been hiding: their grandfather is getting worse.

Inside the house, the truth can’t be avoided. Their grandfather greets Tess warmly, then mistakes Ivy for their dead mother and confuses which granddaughter is which. Ivy immediately takes control. She says they can’t stay on the ranch anymore, that their grandfather needs specialized care, and she’s already arranged a top treatment center in Boston. Tess protests, insisting he belongs at home, but their grandfather—clear enough to decide—sides with Ivy.

Within days, Tess helps check him into the facility and boards a flight east with Ivy, furious, guilty, and grieving all at once.

Washington, D.C., feels like another planet. Ivy lives in a sleek house with security, staff, and a driver-assistant named Bodie who treats sarcasm as a second language. Tess gets a bare bedroom and a credit-card-level assurance that anything she wants can arrive today. Ivy also makes it clear that certain rooms are off-limits because they’re for work.

Tess barely understands what Ivy does now, beyond being rich, connected, and constantly in motion. The next morning, Tess overhears Ivy arguing with Adam Keyes, a controlled, wary man who says bringing Tess to D.C. was impulsive and dangerous. Their tense exchange ends when Ivy gets a call: Chief Justice Theodore Marquette has suffered a heart attack and might not survive, and the press will swarm if the news breaks. Ivy switches instantly into crisis mode and leaves.

Tess recognizes the name. Marquette is a national figure, and in D.C., that makes everything political.

Hardwicke, Tess’s new school, is elite in a way she never imagined. Ivy knows the headmaster personally and demands privacy. Tess is assigned a guide, Vivvie Bharani, whose bright energy makes the place tolerable. Vivvie explains the social hierarchy: Maya Rojas, Di—the reckless daughter of an ambassador—and Emilia Rhodes, a brilliant ice-queen who studies people like puzzles.

Vivvie also tells Tess that Ivy is famous as a fixer, someone who makes humiliating problems disappear for the powerful. Tess decides that won’t be her life.

On her first day, Tess finds a younger student sobbing in the bathroom because some boys have compromising photos of her. Tess storms into the boys’ bathroom, physically takes their phone, and scares them into backing down by laying out the legal consequences. She later learns the girl is Anna Hayden, the vice president’s daughter. The story spreads fast, and Tess gains a reputation she never wanted.

Emilia corners Tess and offers money to fix her troublemaking twin brother, Asher. Tess refuses. She doesn’t want to be Ivy, and she doesn’t want favors tied to transactions.

That boundary lasts less than a day. Students start approaching Tess in class, asking her to “handle” their problems. By lunch, she’s already fed up. She chooses to sit with Vivvie instead of Emilia’s clique, noticing Vivvie’s loneliness and uncertainty.

Before they can talk much, Vivvie freezes, staring toward the chapel roof. A boy stands at the edge, toes hanging over open air. Tess climbs up before teachers arrive and finds him infuriatingly calm. He introduces himself as Asher Rhodes, all jokes and dangerous charm. He claims he was just enjoying the view. Tess drags him down and covers for him with a quick lie.

Teachers accept his excuse with barely a reprimand. Asher tells Tess she’ll soon learn why people let him get away with things. Rumors spread that Tess has taken Asher on as a “case,” cementing her fixer label.

The next morning, breaking news interrupts class: Chief Justice Marquette dies during surgery. Shock ripples through the room, and everyone looks at Vivvie—her father, Major Bharani, is the White House physician who announces the death. Vivvie disappears for days afterward. Tess is unsettled by Vivvie’s fragility and by how D.C. treats death like a chess move.

Ivy drags Tess to a society tea to force her to accept this new world. In the middle of it, security clears the room for First Lady Georgia Nolan. Georgia is polished and warm, yet every word reminds Tess that power can smile. She hints at threats against her, mentions William Keyes pressing Ivy about the Supreme Court nomination, and invites the sisters to dinner.

At school, trouble continues to find Tess. John Thomas Wilcox, one of the boys she confronted, grabs her wrist and threatens her. Asher slides in beside her, loudly calling Tess his friend until Wilcox retreats. Soon after, Headmaster Raleigh summons Tess over anonymous complaints accusing her of bullying and theft. He wants to search her locker. Tess refuses and drops Ivy’s name.

Adam Keyes arrives as a family friend and pressures the headmaster into backing down. Adam later teaches Tess to drive and gently pushes her to attend Marquette’s funeral with Ivy, since Ivy hates funerals and would otherwise be alone.

The funeral is a spectacle of authority: the president delivers the eulogy, dignitaries line up, and cameras hover. Tess watches Ivy’s face harden into the professional mask she uses to survive. Afterward, William Keyes approaches Ivy with cold contempt, clearly a man who once held power over her.

At the wake, Ivy manages press and security, but Henry Marquette—the justice’s grandson and Tess’s classmate—rejects her help. Tess wanders outside and meets Thalia Marquette, sharing a quiet moment away from the spotlight. Asher joins them, then Henry storms in and orders everyone inside. Vivvie appears with her father. Major Bharani scolds her harshly for embarrassing him, then turns polite to others, leaving Vivvie shaken.

That night, Tess searches Bharani online, worried about Vivvie. On Monday, Tess skips class with Asher and goes to Vivvie’s house. Vivvie answers bruised and exhausted. She insists her father didn’t hit her but admits he grabbed her after the wake. Then she breaks: she thinks her father murdered Justice Marquette. She heard him rehearsing the death announcement before Theo died and later overheard him on a disposable phone, reading an account number.

Vivvie won’t accuse him without proof but begs Tess to help identify who he called. Tess agrees. Asher overhears everything.

Before they can act, Vivvie’s father dies. Ivy and Tess come home to find William Keyes confronting Ivy, demanding she support Judge Edmund Pierce for the Supreme Court seat. Georgia Nolan shuts him down. As he leaves, Keyes casually reveals Bharani shot himself.

Tess is horrified, convinced their suspicions caused it. Ivy insists it’s not Tess’s fault and refuses to explain her own actions. Tess runs, panicked and sick with grief. Later, Asher calls while drinking with Henry. He blurts that Bharani killed Theo and then himself. Henry takes the phone, furious and demanding answers.

Tess asks Henry to pick her up and tells him everything: Vivvie’s suspicions, the disposable phone with two numbers hinting at a third conspirator, and the motive—opening a Supreme Court seat so Pierce could be nominated. Henry distrusts authorities and Ivy, who once covered up his father’s suicide. Tess and Henry decide to investigate alone.

Tess sneaks into Ivy’s office and finds a folder of childhood photos Ivy kept—proof Ivy isn’t as indifferent as she pretends. She also analyzes a framed photo she secretly captured from the headmaster’s wall. Clearing the glare, she identifies the men: Bharani, Pierce, Headmaster Raleigh, William Keyes, Congressman Wilcox’s father—and shockingly, President Nolan. Ivy sees the photo, confiscates Tess’s phone, and flies to Arizona to investigate Pierce’s past.

Tess reaches Vivvie, who is burying her father quietly to protect his military legacy. Vivvie fears he was killed to silence him. Back at school, Henry learns Theo attended a Keyes Foundation gala the night before collapsing, making poisoning possible. The photo appears to be from a Camp David retreat Keyes organized through a Hardwicke auction.

Georgia Nolan summons Tess, probing her about Ivy’s Arizona trip and downplaying leaks about Pierce’s nomination. That afternoon, police stop Bodie at gunpoint and take him in. Adam calls it a warning from Keyes to pressure Ivy. Ivy returns and begs Tess to trust her.

But with Pierce’s nomination accelerating and Vivvie desperate, Tess chooses her own path. She uses Emilia’s network to arrange a meeting with a Washington Post reporter’s source, planning to force the truth out.

The plan explodes. Tess is kidnapped and tied to a chair in a basement by Damien Kostas, a Secret Service agent involved in the conspiracy. A disposable phone rings endlessly in his bag. Kostas admits he murdered Bharani when the doctor became a liability and also killed Pierce and a reporter to cover his tracks.

He explains Pierce promised to fix Kostas’s problem—his son on death row in Arizona. Pierce needed Marquette dead to open a seat, so Kostas helped assassinate the chief justice. When Pierce failed to deliver, Kostas took revenge and spiraled into further murders. Now he’s blackmailing the president for a pardon by holding Tess.

Kostas forces Tess to call Ivy, proving she’s alive, and gives Ivy twelve hours. Tess spends the night fighting her bonds until her wrists bleed. Ivy arrives alone. Kostas threatens Tess with an air-bubble injection. Ivy demands Tess be freed first and offers herself instead, revealing she has an insurance system that will expose secrets if she disappears.

Kostas agrees. He frees and sedates Tess, keeping Ivy. Tess wakes in a rainy D.C. alley, alive but panicked. Adam picks her up. At his apartment, Tess tells Adam and Bodie everything. They explain Ivy already suspected a traitor and traced Pierce’s Arizona case to Kostas’s son.

The president visits with proof Ivy is alive but strapped to a bomb. He says the government won’t negotiate. Tess, Asher, Vivvie, and Henry scramble for another solution and realize the Arizona governor can pardon Kostas’s son.

Tess goes to William Keyes despite hating him. She attempts blackmail by implying Adam is her father. Keyes deduces the truth: Tess’s real father was Adam’s younger brother Tommy, making Tess his granddaughter. He agrees to push the pardon if Tess accepts his terms—public loyalty, a trust fund, regular dinners, and a new identity under his control.

The hostage crisis unfolds at the closed Washington Monument, broadcast live. Tess watches as Keyes texts that the pardon is granted. Ivy is released, the bomb disarmed, and Kostas surrenders—only to be shot dead before he can speak.

Ivy believes another conspirator remains. When she reunites with Tess, relief collides with fury and unfinished business. A week later, Keyes arrives at Hardwicke in a limo and publicly claims Tess as his granddaughter and heir, announcing her new name: Tess Kendrick Keyes.

Ivy confronts him, but Tess keeps her promise—his influence saved Ivy’s life. Tess leaves with Keyes into a future shaped by power she never wanted, while Ivy continues investigating from the shadows, certain the conspiracy isn’t fully over and knowing Tess is now inside the very system that nearly destroyed them both.

Characters

Tess Kendrick

Tess is the emotional and ethical core of The Ruling Class: fiercely principled, quick to confront cruelty, and unwilling to trade conscience for comfort. Her instinct to defend Ryan from Mr. Simpson’s humiliation—and later to rescue Anna Hayden from exploitation—shows a reflexive courage rooted less in reputation than in a ranch-bred rule: if someone is being hurt and you can stop it, you do. Under that toughness sits a gnawing fear and guilt tied to her grandfather’s decline and Ivy’s long absence.

That grief makes Tess volatile early on—guarded, angry, and desperate to cling to the ranch as the last stable thing she knows. But in D.C., she adapts fast. She doesn’t crave power, yet she learns how it works, realizing integrity alone can’t beat a system designed to protect itself. Her arc shifts from reactive protector to deliberate investigator: she begins by throwing herself at bullies and ends by assembling evidence, negotiating with monsters, and accepting compromises that unsettle her. Even then, Tess is powered by loyalty and empathy, not ambition—why Vivvie trusts her, why Asher can’t look away, and why she risks everything for Ivy. The revelation about her lineage doesn’t change her character, but it magnifies the danger of what she might be forced to become: someone trying to keep a conscience while inheriting a world built on leverage.

Ivy Kendrick

Ivy is controlled power wrapped around buried tenderness. Publicly she’s a legendary fixer, operating in the shadow world of political crisis management, wearing competence like armor—decisive, feared, and always thinking ten moves ahead. Privately she’s the sister who left without explanation and returns with rules, distance, and a life engineered to keep feeling at bay. To Tess, Ivy’s decision to remove their grandfather from the ranch reads as cold; in truth, it’s love expressed through logistics and necessity rather than comfort.

Ivy’s defining trait is responsibility taken to an extreme. She assumes blame for outcomes she can’t control, tries to “solve” Tess’s happiness like a negotiation, and carries grief so quietly it looks like emptiness—from their mother to Theo Marquette to everything she’s sacrificed to remain functional in the ruling ecosystem. When she trades herself for Tess, the myth cracks open: Ivy’s power isn’t only manipulation, it’s self-sacrifice, and she measures love by what she’s willing to lose. Still, secrecy is her fatal habit. She withholds information because she believes only she can bear it, and that isolates her from Tess, keeping the sisters locked in a dance of trust and betrayal. By the end, Ivy embodies the paradox of competence in a corrupt world: she can save lives, but she can’t easily save relationships.

Grandfather (Tess and Ivy’s guardian)

Their grandfather is both Tess’s anchor and the catalyst for everything that follows. On the ranch, he represents a gentler kind of authority—a man who takes in damaged horses and, by extension, damaged people. Tess’s instinct to protect the vulnerable is clearly shaped by the ethic he lives by. His cognitive decline is rendered as quiet tragedy—clear affection one moment, disorienting confusion the next—and the unpredictability forces Ivy into action and Tess into grief.

Though he largely disappears from the page after the move, his presence lingers as Tess’s internal compass. He embodies the life Tess is losing and the kind of care she fears D.C. will grind away: patient, local, humane. His deterioration exposes the sisters’ opposing survival styles—Tess clinging to emotional truth, Ivy clinging to logistical reality. Even in vulnerability, he keeps dignity, and his agreement with Ivy about leaving the ranch becomes a brutal lesson: love sometimes means surrendering what you want.

Bodie

Bodie brings levity, protection, and a streetwise window into Ivy’s orbit. As Ivy’s driver and assistant, he lives at the edge of power: close enough to understand the machinery, far enough to keep a human perspective. His humor softens the cold precision of Ivy’s household and gives Tess a reluctant ally. Under the jokes, he’s observant and cautious—reading danger early, steering Tess away from traps, and helping her piece herself back together after the kidnapping.

Bodie’s loyalty to Ivy is unwavering, but he becomes quietly loyal to Tess too, filling the role of a stabilizing older-brother figure. Through him, the book shows how non-elites survive among elites: by being indispensable, reading rooms fast, and caring without being naïve.

Adam Keyes

Adam is restraint made human—polite, guarded, and permanently braced for fallout. He carries the weight of the Keyes name while remaining wary of what that name costs, and his discomfort about Tess’s arrival hints at old wounds with Ivy and deep entanglement in political warfare. His steady presence contrasts with Ivy’s controlled intensity and Tess’s impulsiveness: driving lessons become a safe ritual, boundaries become a lifeline, and practicality becomes a kind of protection.

Yet Adam isn’t emotionless. His protectiveness of Tess and complicated loyalty to Ivy reveal a man trying to do right inside a family that treats people like pieces. He functions as an adult anchor as the plot tightens, but his inability to fully step outside his father’s gravity highlights a theme of inherited obligation. Adam represents the fragile possibility of decency inside the ruling class—decency that’s always under siege.

William Keyes

William Keyes is the clearest embodiment of the ruling ecosystem’s predatory logic: confident, entitled, and used to collecting debts. His history with Ivy is layered—once patron, now adversary—and he views relationships as transactions and loyalty as property. His fury when Ivy won’t back Pierce reveals a man who expects obedience because he believes he built the playing field.

Keyes is chilling precisely because he’s sharp. He reads people quickly, deduces Tess’s paternity with surgical precision, and turns a hostage crisis into a legacy opportunity. His deal with Tess is both rescue and capture: protection and resources offered in exchange for identity control and public ownership. He isn’t a cartoon villain; his idea of love may be real to him, but it’s expressed through domination, inheritance, and branding. He is the seductive danger of power calling itself care.

Vivvie Bharani

Vivvie enters as warmth and social clarity—an energetic guide who maps Hardwicke’s terrain with humor and empathy. Her kindness isn’t performative; she notices Tess’s discomfort, offers companionship without agenda, and carries loneliness beneath her brightness. When her father’s role in Marquette’s death becomes suspect, Vivvie’s life collapses into private terror. Her bruises and reflexive loyalty expose a girl trapped between love, fear, and moral horror.

Her confession to Tess becomes the emotional hinge of the story: she wants justice, but she can’t bear to destroy the man who raised her, and she needs Tess because Tess acts without calculating status. After her father’s death, her grief is tangled with suspicion and shame, and the quiet burial underscores how reputation can outrank mourning in elite circles. Vivvie remains brave in a different register—by telling the truth, asking for help, and surviving.

Asher Rhodes

Asher is a chaos artist with a philosopher’s shadow. Introduced on a roof making danger look like a joke, he cultivates untouchability as both armor and entertainment. His charm is sharp and theatrical, and he delights in cracking people’s expectations—especially Tess’s. But the thrill has an edge: his need to go high so everyone looks smaller hints at emptiness, boredom sliding toward nihilism, and a hunger to feel above the structures that contain him.

Asher’s bond with Tess is built on friction and recognition. He’s drawn to her because she can’t be bought; she’s unsettled by him because his recklessness exposes how soft the system becomes for the privileged. Even his antics read as tests—proof of immunity, proof of consequence-free falling. Still, he’s capable of loyalty and protection, stepping in when Tess is threatened and joining the improvised investigative team. He is both a product of privilege and a boy searching for something real enough to interrupt his boredom.

Emilia Rhodes

Emilia is ambition sharpened into polish. She reads people quickly, speaks in transactions, and moves through Hardwicke like someone already inhabiting the future she intends to claim. Her request that Tess “fix” Asher—and her instinct to offer money and favors—reveals how she frames problems: everything is solvable, and solutions are purchased with leverage.

Emilia’s power is quieter than Asher’s. Where he disrupts, she builds—networks, obligations, narratives. She isn’t overtly cruel, but she is pragmatic and unsentimental, and her assumption that Tess is a fixer reflects her belief that value is functional. Over time she can become an ally, but even her allyship carries strategy. Emilia represents the version of elite success that thrives by anticipating needs and controlling stories—a mirror of what Tess might become if survival required trading empathy for efficiency.

Henry Marquette

Henry is grief wrapped in authority. As the chief justice’s grandson, he’s used to orbiting power, but Theo Marquette’s death snaps that orbit into rage and distrust. He meets Tess and Ivy with guarded hostility, protective of privacy and wary of Ivy’s fixer reputation. When Tess shares Vivvie’s suspicions, Henry responds with furious logic—wanting procedure, demanding answers, resisting backchannel games.

That faith corrodes as the conspiracy’s reach becomes clear and as his history with Ivy—especially her past role in covering up his father’s suicide—reopens old wounds. Henry’s arc is a collision between idealism and reality: he wants law to govern, but learns law can be costume and weapon. His partnership with Tess is tense, built on necessity and sharpened by ideological conflict, yet it deepens into trust forged through shared loss. Henry embodies the tragedy of inheriting both privilege and pain—and trying to use one to redeem the other.

Thalia Marquette

Thalia appears briefly but meaningfully as a soft counterpoint to the Marquette family’s formal grief. Her wandering, her small rebellions, and the quiet moment she shares with Tess suggest someone who processes sorrow through fragile, almost childlike freedom. She is open where Henry is armored, and her presence highlights the range of ways privileged families metabolize trauma—some harden into control, others reach for fleeting escape. Thalia gives Tess a rare, uncomplicated connection in the middle of spectacle, reminding her that mourning can still be human.

Major Bharani

Major Bharani is a chilling portrait of sanctioned authority turned monstrous. Publicly he is disciplined, composed, and patriotic enough to announce the chief justice’s death on national television. Privately he is controlling and violent toward Vivvie, obsessed with reputation, and enmeshed in lethal conspiracy. His involvement shows how ideology, ambition, and “service” can fuse into moral collapse—how the posture of duty can hide cruelty.

Even his death sits in ambiguity, whether self-inflicted or orchestrated, and reads like the end of a man who believed he could manage outcomes without consequence. Bharani functions as a warning about how intimate state power can become with personal brutality—and how easily the righteous language of service can mask depravity.

Chief Justice Theodore “Theo” Marquette

Theo Marquette is the moral vacancy at the plot’s center, present mostly through absence. As chief justice he represents institutional legitimacy; his death triggers political chaos and exposes how fragile that legitimacy is. The funeral and wake clarify his stature, while Henry’s grief and Ivy’s hidden history with him suggest a life both respected and compromised. His final days—social proximity to the Keyes machine and then sudden collapse—hint at how even the highest judicial authority remains vulnerable to elite networks. In the story, he becomes the symbol of a system where the strongest emblems can be removed for strategic gain.

President Nolan

President Nolan sits at the top of the visible hierarchy without being truly untouchable. His presence in the Camp David photo places him uncomfortably close to conspirators, raising questions about complicity, leverage, and manipulation. During Ivy’s hostage crisis, he adopts the official posture of refusing to negotiate, yet his actions reveal constraint—boxed in by politics and the machinery around him. Nolan represents how elected power can be trapped by unelected influence, and how even the presidency can become another piece on someone else’s board.

First Lady Georgia Nolan

Georgia is a nuanced political actor: warm in presentation, sharp in intention. Her tea-room entrance is practiced—an effortless display of intimacy with elite space—yet it also functions as surveillance. She frames herself as threatened, but uses that framing to justify intrusion and control. With Tess, her friendliness is calibrated, subtly testing what Tess knows and how close Ivy is to disrupting Keyes’s agenda. Georgia embodies the social face of governance, where charm, diplomacy, and information-gathering blend into weaponized grace.

Damien Kostas

Kostas is desperation turned violent. As a Secret Service agent, he should represent protection; instead, his betrayal turns the state’s shield into a weapon. His motive is brutally personal—saving his son from a death sentence—and that fear curdles into assassination, cover-ups, and nihilism. He kidnaps Tess, bargains for Ivy, and blackmails the president because he believes he’s already crossed every line worth fearing.

Kostas is also perceptive, understanding why Ivy’s “insurance” makes her the more valuable hostage. His death on camera before he can speak reinforces the book’s central warning: the most dangerous truths are often silenced by someone still unseen.

Headmaster Raleigh

Raleigh is an institutional gatekeeper whose authority bends toward status. He moves quickly to punish Tess on flimsy accusations, then hesitates the moment Ivy’s name enters the room—revealing Hardwicke as a microcosm of elite society, where rules exist but consequences are distributed by power. His inclusion in the Camp David photo suggests he is not merely an administrator but part of the adult network that fuses education, politics, and influence. Polite and cautious, he ultimately functions as complicit infrastructure.

Mr. Simpson

Mr. Simpson is the book’s first face of everyday tyranny: a teacher who uses authority and intellect as weapons. His humiliation of Ryan and attempt to belittle Tess establish the opening moral landscape—power as casual cruelty, normalized behind roles and tradition. He isn’t part of the grand conspiracy, but he introduces the theme that domination often starts small, in ordinary rooms, with people who assume they’ll never be challenged. Tess challenging him is the first signal of who she is.

Ryan Washburn

Ryan is introduced as shy and easily targeted, serving as the immediate victim that sparks Tess’s defiance. His vulnerability triggers Tess’s compassion and connects to her experience with wounded animals on the ranch. While he doesn’t drive the later plot, Ryan clarifies Tess’s internal rulebook and foreshadows her willingness to confront larger, more dangerous bullies later on.

John Thomas Wilcox

Wilcox is elite entitlement in teenage form. He retaliates against Tess for humiliating him and his friends, weaponizing status, intimidation, and the school’s rumor economy. His aggression—especially the physical threat—shows how privilege teaches boys to expect immunity. He’s less a complex individual than a preview of how the ruling class reproduces itself: entitlement passed down until it feels like instinct.

Maya Rojas and Di (“Diplomatic Immunity”)

Maya and Di help build Hardwicke’s social ecosystem, illustrating its globalized elite culture where international politics is family background noise. Their swagger and nicknames emphasize that for these students, power is inheritance and atmosphere. They function more as context than drivers, showing the world Tess must decode to survive.

Anna Hayden

Anna’s appearance is brief but symbolically loaded. As the vice president’s daughter, she shows how quickly Tess’s morality gets converted into elite currency. Tess rescues her without knowing who she is, yet Anna’s status turns a simple act of decency into a story that reshapes Tess’s reputation. Anna represents how power can turn ordinary goodness into a headline—and how forces beyond intent can define a person’s narrative.

Judge Edmund Pierce

Pierce is the ambition that makes the conspiracy profitable. Even when he’s mostly seen through rumors and aftermath, his hunger for the Supreme Court seat is the engine behind murder, manipulation, and blackmail. His willingness to promise Kostas relief for his son shows a man treating justice like barter. Pierce’s fate—and how the machine keeps moving—exposes a grim truth: in this world, people die, but the agenda doesn’t.

Tommy Kendrick Keyes and Tess’s parents

Tess’s parents are absent but structurally present. Their deaths create the hollow space Ivy tried to fill and Tess still aches around, explaining Tess’s fierce attachment to her grandfather and terror of abandonment.

The revelation that Tommy is Tess’s father re-frames Tess’s position inside the Keyes dynasty, giving her a blood claim to the very class she resists. Their legacy lives in Tess’s stubborn moral spine and Ivy’s protective guilt—binding the sisters together even when they can’t speak the same emotional language.

Themes

Power, Privilege, and the Closed World of the Elite

From the moment Tess lands in Washington and steps into Hardwicke, the novel traps her inside a social ecosystem where power is both normalized and suffocating. The students aren’t simply teenagers—they’re the children and heirs of presidents, ambassadors, judges, senators, and donors, and that inheritance shapes every conversation in every hallway. Someone like Asher can stand on a roof and walk away with a mild scolding because consequence is negotiable when status is generational.

Hardwicke’s authority is revealed as performative the instant Headmaster Raleigh pivots when Ivy’s name is mentioned: the institution meant to educate also functions as a gatekeeping machine for the powerful. Even gossip behaves differently here. Tess’s single act of courage gets converted into a brand—“fixer”—because the elite interpret behavior through utility and influence, not character.

Outside the school, the political world runs on the same logic. William Keyes treats a Supreme Court nomination like a chess piece; Georgia Nolan manages threats and optics as routine; Ivy’s entire career depends on shaping narratives for people who believe they’re entitled to escape fallout. Power in The Ruling Class isn’t always loud—it’s embedded in who gets believed, who gets searched, who gets shielded, and who gets sacrificed. Tess’s outsider status matters because it keeps the normalization visible. She reacts with ranch-bred bluntness in rooms designed to reward polished silence, and the book sharpens its critique by showing privilege not only as wealth or access, but as a mindset that assumes problems can be erased, people can be managed, and truth can be used. The ruling class survives through resources—and through shared habits of protecting their reality at any cost.

Moral Courage Versus Complicity

A central tension shadows Tess’s choices: speak up and risk punishment, or stay quiet and become part of the machine. Her first confrontation in the history classroom is small in scale but huge in meaning—she corrects a teacher who humiliates a weaker student, and the system responds by treating her as the problem. That pattern repeats as the stakes climb.

Tess resists becoming a fixer because “fixing” sounds like hiding wrongdoing, and she wants her actions to mean more than damage control. But the plot keeps her in gray zones: she lies to protect Asher on the roof, breaks into offices, withholds information from police, and plans leverage against people who may be guilty. Each choice presses the same question—can you refuse complicity inside a world built on favors, silence, and sealed scandals?

Vivvie intensifies the theme. She suspects her father of murder, yet can’t emotionally cross the line of accusing him. Loyalty to a parent collides with loyalty to truth, and that paralysis becomes catastrophic. Ivy offers the other side of the argument: years of bending rules for powerful clients have made her effective, but not clean. Tess watches Ivy accept blame through association because in this world guilt spreads like smoke. The conspiracy itself thrives because people tolerate “small” wrongdoing for a promised greater good—until the wrongdoing becomes lethal. By the end, Tess isn’t saintly; she’s sharpened. The novel frames courage not as one heroic moment, but as a chain of pressured decisions made without clean exits, where refusing to look away can save someone—and looking away can destroy them.

Family Loyalty, Betrayal, and the Search for Belonging

The emotional engine of the story is Tess’s fractured family life and the way love becomes tangled with control. Her grandfather’s decline forces the first rupture: the person who anchored her identity is no longer stable, and Tess is uprooted before she’s ready. Ivy’s return is both rescue and betrayal. Tess remembers Ivy leaving three years earlier without explanation, so Ivy’s authority in Washington feels unearned—yet Ivy is also the one fighting to keep Tess safe.

Their relationship runs on unfinished history. Ivy sets rules, reaches for connection awkwardly, and repeatedly makes unilateral decisions; Tess responds with silence and defiance because being moved around feels like being abandoned all over again. This push-pull becomes Tess’s internal battleground: she’s furious at Ivy for managing her like a problem, but she also aches for proof she matters. The childhood photo folder Tess finds in Ivy’s office becomes a quiet pivot point—evidence that Ivy’s love has always existed, just filtered through distance and secrecy.

Then the theme tightens into something more dangerous when William Keyes claims Tess. His offer of wealth and status is wrapped in ownership: public identity control, expectations, and a future mapped by someone else. Tess accepts because Keyes saves Ivy’s life, but the choice is not simple gratitude—it’s another loyalty pact with a cost. She keeps a promise that wounds Ivy and binds Tess to a man who treats family as legacy strategy. Even the Marquettes echo this theme: Henry’s inability to trust Ivy is rooted in a past cover-up tied to his father’s death. In The Ruling Class, family is not a soft refuge—it’s a battlefield of obligation, secrecy, and competing definitions of protection. Tess’s coming-of-age is partly the attempt to define belonging on her own terms: loving Ivy without surrendering herself, honoring her grandfather while accepting reality, and stepping into a new lineage without letting it rewrite who she is.

Truth, Secrecy, and the Cost of Controlling Narratives

In this world, information behaves like currency, weapon, and liability at once. Tess arrives in Washington already shaped by secrecy—her grandfather’s decline, Ivy’s absence, and the feeling that the truth is always slipping just out of reach. Once she’s inside the political sphere, secrecy becomes oxygen. Ivy’s career exists because the powerful need truths buried quickly, and even her home is built around locked doors and “off-limits” rooms.

Hardwicke shows how reputation can become a manufactured truth overnight. Tess rescues Anna Hayden without knowing who she is, and immediately loses control of her own story as the act turns into a social legend. When the chief justice dies, rumors and press dynamics shape perception before facts can surface. Vivvie’s suspicion exposes the human cost of secrecy: she carries knowledge that could rupture a conspiracy, but revealing it would also destroy her family. Her silence—fear braided with love—isolates her until tragedy forces the secret into motion.

The disposable phone and the enhanced photo operate like thematic symbols: evidence is fragile in a world designed to blur it with glare, spin, and intimidation. Even when Tess and Henry uncover proof linking major figures, it doesn’t produce justice—it produces more secrecy: confiscated phones, redirected investigations, police stops meant to frighten them into silence. The state itself is shown as both protector and manipulator; power can look sympathetic while functioning as a network that treats death as collateral. By the time Kostas kidnaps Tess, secrecy has escalated from career management to life-and-death leverage. Ivy’s “insurance program” pushes the theme to its bleakest clarity: survival at the top depends on your ability to control narratives—or threaten to detonate them. The novel argues that truth is never only about facts; it’s about who can reveal, bury, or reframe them, and the cost of living inside controlled stories is permanent distrust.

Trauma, Resilience, and Coming of Age Under Pressure

Tess’s toughness isn’t performative—it’s forged by loss and proximity to pain.

Her parents are gone, her grandfather is failing, and her life has trained her to handle fear by acting. That instinct shows in how she calms abused horses, confronts bullies, and intervenes immediately when Anna’s photos become leverage. The story repeatedly crashes adult-level crises into teenage space, forcing Tess to grow faster than she wants to.

In Washington, luxury doesn’t comfort her; it disorients her. Grief follows her through flights, funerals, and constant reminders of how easily power can reach into a life and rearrange it. Vivvie’s bruises and shutdown reveal another kind of trauma: respectable suffering hidden behind polished doors, where image matters more than safety. Asher’s recklessness becomes another mask—chaos as self-medication for expectation, emptiness, and loneliness.

The kidnapping sequence becomes the most brutal test of resilience. Tess is restrained, bleeding, and facing an adult who expects to die, yet she keeps questioning him because understanding still matters to her even in terror. Her survival isn’t framed as instant recovery; she’s shaken, guilty, frantic, and still trying to save Ivy. And the ending refuses to hand her an easy victory.

Accepting Keyes’s terms buys security and costs freedom, giving her a new cage made of identity, obligation, and public narrative. Resilience, then, becomes complex: Tess endures, adapts, and keeps moving, but learns that staying alive in this world may require compromises she hates. The Ruling Class frames coming of age as learning to carry trauma without letting it dictate your ethics—and holding onto empathy when the world insists hardness is the only safe posture.