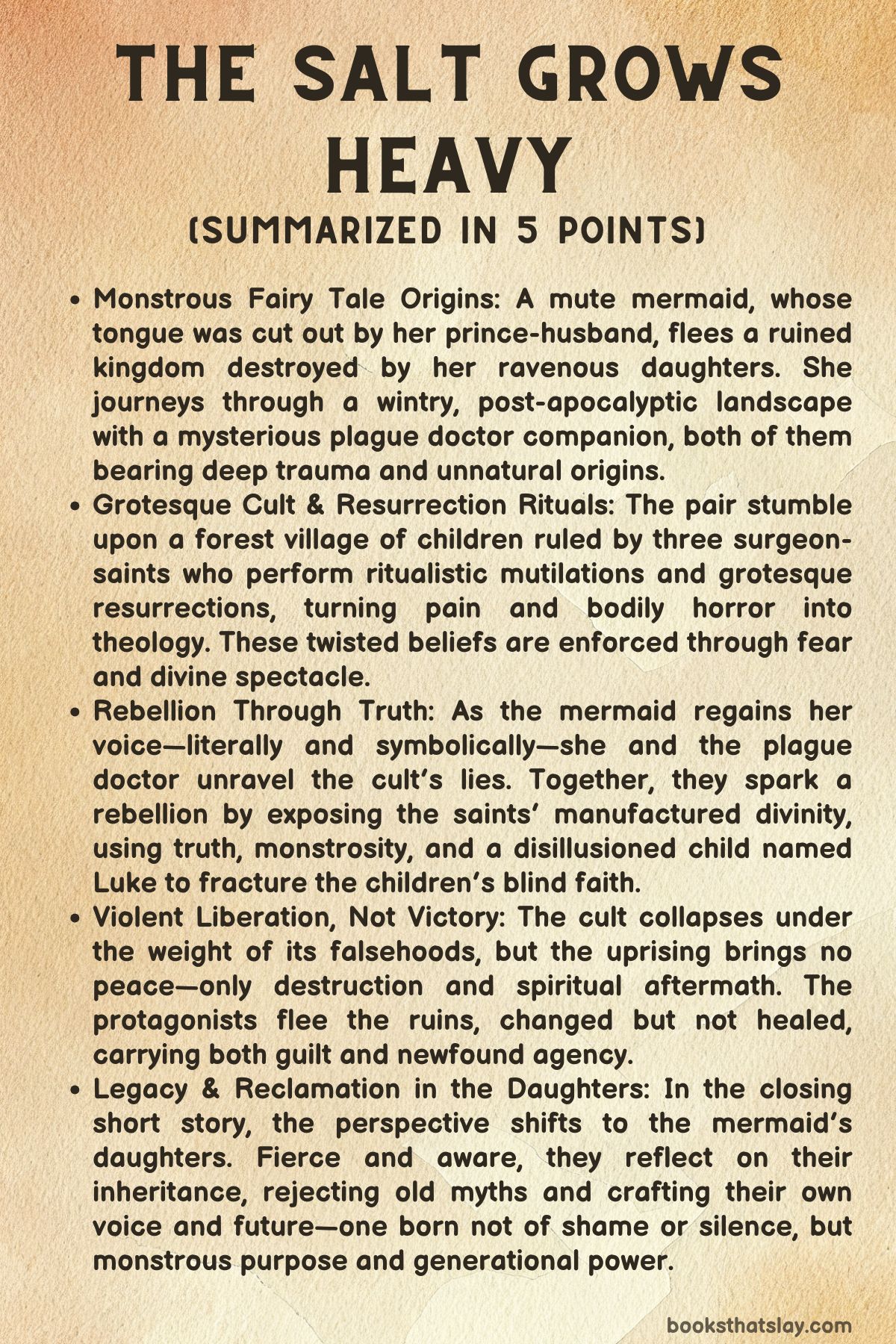

The Salt Grows Heavy Summary, Characters and Themes

The Salt Grows Heavy by Cassandra Khaw is a lush, blood-soaked fairytale retelling spun with horror, body lore, and lyrical prose.

At its heart is a mute mermaid—no Disney heroine, but a savage, haunted being—traveling through a surreal, post-apocalyptic world alongside a mysterious plague doctor. The story unfolds like a fever dream, layered with unsettling beauty and grotesque rituals, interrogating what it means to survive, to reclaim agency, and to be monstrous in a world that worships suffering as salvation. Through poetic horror and twisted myth, Khaw crafts a brutal meditation on identity, autonomy, and generational transformation.

Summary

The Salt Grows Heavy begins after devastation.

A mermaid—once silenced by her prince-husband who mutilated her—wanders a snowy wilderness with a plague doctor. Her daughters, birthed from a violent union between predator and man, have destroyed the kingdom and devoured its people.

Now, she is alone with her enigmatic companion, a being as stitched and broken as she is, whose identity blurs the line between human, construct, and memory.

Their path leads them into a strange cult-like village deep in the taiga, where only children remain—children who worship three masked figures known as the “saints.”

These saints, surgeons masquerading as divine beings, perform grotesque resurrections on the dead, slicing out bezoars from corpses and reanimating them through ritualistic, surgical rites. The children kill and resurrect each other as if playing god is a game.

The mermaid and plague doctor are horrified, but the doctor—more disturbed—reveals that he, too, was created by such surgeons, a child shaped by the same ideology now twisted into divine doctrine.

Over the course of three nights, their journey shifts from passive observation to resistance. On the first night, the mermaid and plague doctor watch in horror as a boy named Luke is murdered and brought back to life by the saints.

The mermaid, now deeply curious about her companion and the children, begins to reflect on her own monstrous children—how they killed and consumed, yes, but without lies or sanctimony. In contrast, this cult of children uses faith to justify torture. The saints preach pain as transformation, and the children, all too eager to transcend, comply.

In the second night, the mermaid eats the discarded remains of the saints—their tongues, livers, eyes—and regains her voice.

Her tongue, once taken from her, is symbolically and physically reclaimed. She speaks again, not only with words but with fury and clarity. The plague doctor reveals his past: he was once a child in a place like this, mutilated into obedience, made into a tool.

Together, they resolve to plant the seed of rebellion. They search for a child among the faithful who is disillusioned enough to see the saints for what they are—flesh, myth, and manipulation.

Their revolution blooms on the third night. With Luke as their reluctant Judas goat, they expose the saints’ lies—showing the children the truth behind resurrection, the decay behind the performance.

The mermaid unleashes her monstrous self: predator, god, and mother, tearing apart the illusion of sanctity. The plague doctor confronts his creators, using memory as a blade. The saints, long revered, fall. Their bodies—stitched and sustained by surgeries—fail under scrutiny and violence. The children revolt, chaos erupts, and fire consumes the village.

In the aftermath, there is no triumph.

Only ash, silence, and escape. The epilogue follows the mermaid and plague doctor as they walk away, both irrevocably changed. He is hollowed by failure and grief. She, fully voiced now, walks with new autonomy—not ashamed of her monstrousness but owning it.

In the final story, the narrative shifts.

Her daughters—carnivorous, intelligent, and observant—look back at what was left behind. They do not follow their mother’s path; they forge their own. They study myths, dissect legacies, and choose a future rooted not in obedience or vengeance, but in self-made identity.

The daughters are no longer echoes—they are authors. Their voices, once background growls, now narrate a new mythos entirely their own.

Khaw closes the tale not with resolution, but with evolution. The salt may grow heavy, but the voice it bears is sharper than ever.

Characters

The Mermaid

The mermaid is the central figure of the story, portrayed as a tragic yet powerful character. Once silenced by her cruel husband, who cut out her tongue, she has been transformed into a being whose body is a mixture of beauty and monstrosity.

Her journey is one of reclaiming agency and power, as she struggles to come to terms with her mutilation, both physical and emotional. As the story progresses, her strength grows—particularly after she regains her voice by consuming parts of the saints’ bodies, symbolizing her reclaiming of autonomy.

Her daughters, a grotesque and terrifying reminder of her past, are part of her monstrous legacy. They devour kingdoms and people alike, continuing her lineage of destruction.

Despite her tragic past, the mermaid is no passive victim; she embraces her monstrosity and uses it to fuel her journey toward survival. Her actions challenge traditional notions of victimhood, as she turns her suffering into a source of power and transformation.

The Plague Doctor

The plague doctor is a character enshrouded in mystery and trauma. They accompany the mermaid throughout her journey, and like her, they are a creation rather than a born being.

Their ambiguous origins, having been created by the very cult they oppose, suggest deep inner conflict. The plague doctor wears a vulture mask, hiding a stitched-together body that speaks to their own tortured identity.

They are emotionally fractured, grappling with guilt and the realization that they, too, have been shaped by the very power structures they seek to destroy. Despite this, the plague doctor serves as a guide and companion, offering insights into the horrific cult they find themselves fighting against.

Their role evolves from a passive observer to an active participant in the rebellion, as they help the mermaid formulate a plan to expose the truth of the saints. The plague doctor’s journey is one of self-discovery, as they use their past and identity as leverage in their quest for justice.

The Saints

The saints, who are central antagonists in the story, represent the perverse intersection of divine belief and physical mutilation. They are depicted as figures of power, immortalized through grotesque surgeries and body modifications that supposedly grant them eternal life.

They manipulate the children of the village, turning them into willing participants in their horrific rituals, including resurrection and the harvesting of human remains. Their belief system is built on the premise that suffering and mutilation lead to transcendence, and they use this doctrine to control their followers.

However, as the story progresses, the saints are revealed to be fallible and dependent on their physical bodies, which gradually deteriorate under the weight of the truths exposed by the mermaid and the plague doctor. They are not divine but human, and their supposed immortality crumbles when their illusions are shattered.

The saints’ twisted theology and their brutal exploitation of the children reflect a critique of authoritarian systems that mask cruelty under the guise of divinity.

Luke

Luke is a pivotal character who represents the impact of the cult’s control on the children of the village. Initially resurrected by the saints in a grotesque and mutilating ceremony, Luke becomes a symbol of the saints’ cruelty and the damage done by their warped beliefs.

His scars, both physical and emotional, mark him as a living example of the horrors wrought by the saints. As he becomes more aware of the truth, Luke plays a crucial role in the rebellion, helping to expose the falsehoods of the cult and inciting other children to question their faith.

His transformation from a passive victim to an active participant in the rebellion underscores the theme of personal awakening and resistance against oppressive forces. Luke’s journey reflects the broader theme of generational trauma, as he is shaped by the violence of his environment but ultimately seeks to break free from it.

The Daughters

The daughters of the mermaid emerge as powerful figures in the epilogue and short story, And In Our Daughters, We Find a Voice. These characters represent the continuation of the mermaid’s legacy, though in a more active and deliberate form.

Unlike their mother, who struggled with her monstrosity, the daughters embrace their nature and view it as a source of strength. They are intelligent, observant, and poised to carve out their own mythologies, unburdened by the old hierarchies that once constrained their parents.

The daughters’ rise marks the beginning of a new generation, one that will not simply inherit the past but transform it. Their voices, symbolizing agency and power, are no longer suppressed or passive.

In their hands, the cycle of violence and power shifts, as they become the mythmakers of a new era. Their final stance reflects a rejection of the saints’ false divinity and an assertion of their own identities and destinies.

Themes

Power, Autonomy, and Bodily Violation

In The Salt Grows Heavy, power and bodily autonomy emerge as central themes, deeply intertwined with the violent transformation of the characters. The mermaid’s silence, initially imposed by the cruel actions of her husband, symbolizes the brutal control over her body and identity.

Her mutilation, represented by the loss of her tongue, becomes a physical manifestation of the stripping away of autonomy, setting the stage for her eventual reclamation of power. Her daughters, monstrous hybrids born from this union, inherit not only her curse but her defiance, showcasing a generational continuity of pain and power.

The plague doctor, too, is a creation—stitched together and designed by the very saints they now aim to overthrow. The theme of bodily violation reaches its peak in the grotesque resurrection rituals, where children’s bodies are mutilated and transformed in the name of divine power.

These acts of mutilation are not just physical but deeply psychological, with the characters grappling with the question of what it means to control one’s own body in a world that seeks to dominate and redefine it.

Identity, Creation, and Trauma

Identity is fluid and fragmented throughout The Salt Grows Heavy, with the mermaid and plague doctor both seeking to understand who they truly are, separate from the forces that shaped them. The mermaid’s journey is not just one of physical survival but of self-discovery.

Her regained voice after consuming the saints’ discarded body parts marks a pivotal moment in reclaiming her identity. No longer silent, she confronts her past, her mutilation, and the trauma of her origins.

Similarly, the plague doctor, who once served as a tool of the saints, must confront the horrors of their own creation—an artificial being, crafted and programmed to uphold a belief system that now feels alien and oppressive.

The concept of creation extends to the monstrous children, who, though born from horrific circumstances, are not simply victims but individuals navigating their inherited trauma, learning to shape their own stories rather than simply repeat the tragedies of their parents.

In the epilogue, the daughters represent the continuation of this theme, stepping into a new identity that challenges the mythologies that defined their parents’ lives. This showcases the possibility of transformation and reinvention.

Resistance, Rebellion, and the Fragility of Belief Systems

Resistance, both internal and external, plays a significant role in the narrative. The characters, particularly the mermaid and the plague doctor, constantly question the world around them and the established systems of power.

The children’s unquestioning devotion to the saints and the cult’s power is a reflection of how belief systems can be manipulated to control and subjugate. The mermaid’s and plague doctor’s actions, from revealing the saints’ grotesque rituals to inciting doubt among the children, illustrate the fragility of these belief systems when confronted with the truth.

The rebellion, however, is not a straightforward victory—it is marked by chaos, confusion, and destruction. In the end, the saints’ own bodies, once symbols of divine immortality, collapse under the weight of truth and rebellion, revealing the fragility of the power structures they upheld.

The epilogue echoes this theme, where the rebellion has not led to a clean resolution but to an ongoing cycle of survival, change, and the birth of new myths. The daughters, now poised to create their own stories, symbolize the continuation of this cycle of resistance, as they reject the old gods and their doctrines to forge their own path.

Legacy, Mythmaking, and the Inheritance of Trauma

Legacy is explored as both a burden and a transformative force. The mermaid’s actions and the destruction of the cult reflect the inheritance of trauma passed down through generations.

Her daughters, however, embody the potential to reshape the legacy of violence and loss. Rather than passively inheriting the myth of their mother’s suffering, they step into their own power, already aware of the stories they will craft for themselves.

This theme is most explicitly expressed in the short story And In Our Daughters, We Find a Voice, where the daughters, now fully aware of their heritage, begin to forge their own identities. The trauma of their parents’ battles is not something they choose to hide from but to confront and reshape into something new.

They reject the old myths that defined their parents’ suffering and instead begin to write their own futures. The narrative suggests that mythmaking is not solely a process of retelling old stories but of creating new meanings from the debris of past pain, and in doing so, the next generation not only survives but becomes the authors of their own legacies.

Sacrifice, Transcendence, and the Corruption of Divinity

The saints in The Salt Grows Heavy present a chilling exploration of sacrifice and transcendence, where bodily mutilation is portrayed as a path to divine immortality. Their belief system, rooted in the idea that pain and sacrifice lead to spiritual elevation, reveals the corruption of divinity.

The saints’ actions, especially the grotesque surgeries and the resurrection rituals, expose the dark side of the notion of transcendent power, where the divine is manipulated for control and domination rather than for enlightenment or salvation.

The mermaid and plague doctor, in their rebellion, challenge this warped ideology, revealing that the so-called divine power is nothing more than a facade, built on pain, manipulation, and lies. The saints’ physical bodies, once symbols of invincibility, collapse under the weight of truth and rebellion, illustrating the ultimate fragility of divinely imposed systems.

The theme of transcendence, then, is not about escaping the physical world but about the reassertion of bodily autonomy and the rejection of systems that demand sacrifice for the sake of power.