The Scarlet Veil Summary, Characters and Themes

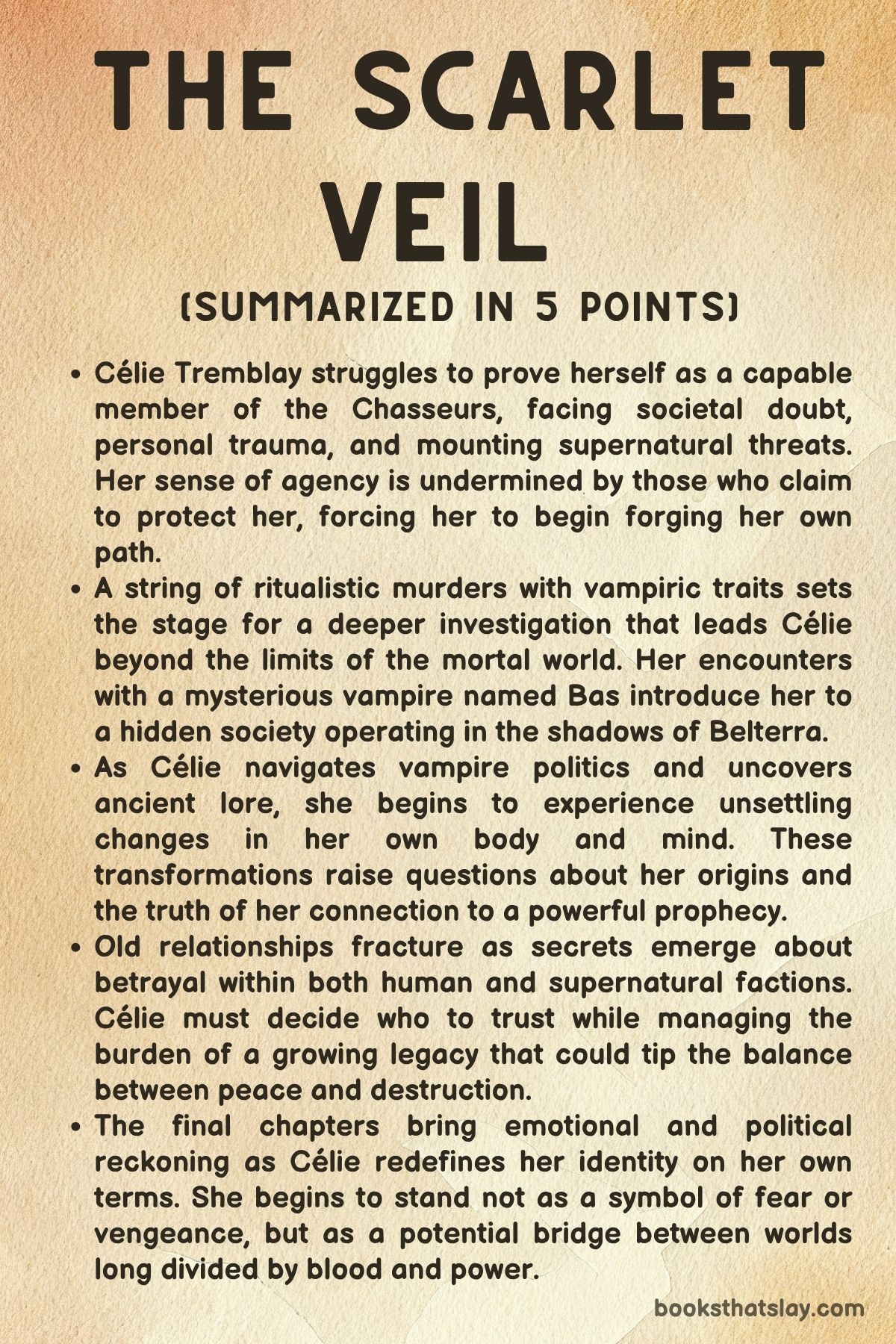

The Scarlet Veil by Shelby Mahurin is a dark fantasy novel set in the gothic world of Belterra, where monsters prowl, secrets fester, and inner battles prove as perilous as any sword fight. At its core is Célie, a young woman burdened by trauma, suffocated by societal expectations, and burning for autonomy.

As the first female member of the Chasseurs—a holy order sworn to hunt magical creatures—Célie finds herself caught between duty and discovery, love and betrayal, and truth and myth. Her journey is one of reckoning, resistance, and reluctant evolution as she confronts both the monsters that threaten her world and the ones buried deep within her own past.

Summary

The story begins with a tender but foreboding childhood memory, where Célie and her sister Filippa listen to tales of the Les Éternels—bloodthirsty, soulless beings who roam the night. These bedtime stories, though seemingly mythical, lay the groundwork for the fears and legends that shape Célie’s understanding of the world.

As Célie grows up in the kingdom of Belterra, she seeks to escape those shadows by proving her worth among the Chasseurs. Yet, even as the first female soldier in their ranks, her achievements are routinely diminished.

Her male comrades, including her fiancé Jean Luc, patronize her efforts, undermining her confidence with veiled condescension. Her world begins to crack when she learns her latest triumph—trapping a supernatural lutin—was engineered to preserve her pride, not to honor her skill.

This revelation not only wounds Célie’s pride but sharpens her awareness of how deeply she is underestimated. Jean Luc’s behavior, protective but opaque, leaves her feeling isolated, especially as he withholds information and secrets from her.

Even her engagement ring, meant to symbolize partnership, becomes a cold reminder of the imbalance between them. Seeking solace, Célie turns to friends—Lou, Coco, Reid, and Beau—who offer momentary reprieve with food and laughter, but not clarity.

Her psyche begins to splinter under the weight of old fears, survivor’s guilt, and a dream in which her sister Filippa—once her moral anchor—emerges as a puppet-master and devourer, a disturbing metaphor for unresolved trauma.

As her emotional turmoil escalates, Célie is subjected to a physical and psychological blow: Frederic, a fellow Chasseur, attacks her during training. Though Jean Luc defends her, he continues to sideline her from key decisions, fueling her resentment.

This alienation peaks when Célie discovers her friend Babette’s lifeless body at her sister’s grave, punctured by vampire fangs. Her grief is compounded by the sudden appearance of a ghostly man—cold, pale, and arrogant—who dismisses her panic and mocks her confusion.

When Jean Luc arrives, instead of empowering Célie, he infantilizes her, pushing her further away from the truth and deeper into frustration.

Her exclusion from the murder investigation is a devastating blow. She hears her name tossed around like an afterthought by men who once called her a comrade, even as they bring her tormentor Frederic into their confidence.

Most hurtfully, Jean Luc portrays her as fragile and emotionally unstable—a narrative that both negates her past triumphs and justifies their paternalism. When she confronts him, demanding recognition and truth, he breaks her spirit with one final confession: he does not believe she killed the witch Morgane, and he doesn’t trust her to defend herself.

This betrayal snaps something within Célie. Rejecting both her engagement and her prescribed role, she sets out alone to seek answers.

Her path quickly becomes entangled with Michal, the cold stranger she met at Filippa’s grave. Their relationship is fraught with distrust, tension, and reluctant dependence.

The two are drawn together by a common goal: finding the true killer behind the vampire attacks. As they investigate, they discover that Michal’s sister Mila has also been turned into a vampire.

Though she cannot remember who attacked her, her story deepens the mystery surrounding the murders and adds emotional stakes to their mission.

Célie and Michal’s alliance is rocky. He manipulates her with tokens of emotional leverage—her engagement ring, her silver cross—and seeks to enlist her loyalty through coercion.

Still, she holds her ground, refusing to sacrifice her values for revenge. Together, they follow a trail that leads them to a ship filled with vampire coffins, where they hide together in a coffin during a violent storm.

This terrifying moment bonds them, revealing new layers of Michal’s vulnerability and Célie’s courage.

Their quest continues in the city of Amandine, where they enter Les Abysses, an underground brothel filled with secrets and rituals. Here, Célie undergoes a prophetic rite overseen by the pythoness Eponine, who forces her to bite into an apple that unveils hidden truths.

The silver cross found with Babette may have once belonged to Filippa, implying a deeply personal link between Célie and the murders. Eponine’s warning—that the killer will find her before she finds them—heightens the stakes.

Célie and Michal are sent to find Pennelope Trousset, Babette’s cousin, hoping for more clarity. With every step, the mystery coils tighter around Célie’s past and identity.

Later, as they take shelter in Requiem, Célie, Lou, and Coco process the trauma of Michal’s ruthless vampire executions. Though shaken, Célie begins to accept her complexity: brave but burdened, changed but not broken.

Lou reaffirms her strength, reminding her of the barriers she has shattered and the hope she has kindled in other women. But Requiem offers no peace.

That night, Célie dreams of a frozen islet, her sister’s corpse lying in a glass coffin, and Michal sleeping vulnerably beside it. When she awakens and shares her vision with him, he confirms that it was an astral projection—not fantasy.

They race to the islet.

There, they find Filippa’s coffin, invisible to the naked eye but marked by blood magic. As they prepare to retrieve her body, Frederic reappears, revealing himself as the necromancer behind the killings.

He has brought Babette back from the dead and plans to use Célie’s blood to resurrect Filippa. Declaring twisted affection, Frederic stabs Michal and drugs Célie, intending to sacrifice her.

Célie wakes beside her sister in a red gown, disoriented but defiant. Frederic, consumed by grief and obsession, explains his past love for Filippa and their secret child, Frostine.

He believes Célie’s blood will restore them both. As he raises the knife, Célie stalls for time, and Michal, half-dead but driven, drags himself ashore.

A chaotic battle erupts. Lou, Coco, and their allies arrive just as Frederic tries to complete the ritual.

Célie fights him but is knocked unconscious.

She enters a liminal space between life and death, where Mila urges her to choose her fate. Observing the chaos from beyond, Célie sees Michal whispering for her to stay, offering his blood to revive her.

She awakens in a boat, heart no longer beating, body cold—but no longer afraid. She is not just a Chasseur or a girl in mourning.

She has crossed a threshold and returned stronger, willing to embrace what she has become. Célie has finally claimed her place in the story, not as a victim, but as a heroine who refuses to be silenced, sacrificed, or forgotten.

Characters

Célie

Célie is the heart of The Scarlet Veil, a character shaped by pain, repression, and defiance. From the earliest scenes, she is haunted by trauma—both personal and collective—stemming from her childhood belief in myths and the brutal reality of her sister Filippa’s death and resurrection.

Her need to prove herself as a capable Chasseur in a patriarchal, magic-fearing society collides with her emotional vulnerability, making her arc deeply compelling. Her journey is punctuated by a constant push and pull between wanting to belong and the need to stand apart.

The humiliation she faces—whether through her fiancé Jean Luc’s patronizing protection, her comrades’ cruelty, or the sting of staged victories—shapes a woman both fractured and fiercely determined.

Célie’s emotional layers are peeled back as she investigates mysterious deaths, facing betrayal from those she trusts and horror from what she discovers. Her recurring dreams, soaked in gothic symbolism, reflect internalized guilt and the tension between her identity and societal expectation.

The most poignant evolution in her character comes when she severs ties with Jean Luc and her symbolic engagement ring, claiming independence and setting forth on a path that is entirely her own. She becomes not just a seeker of truth but a symbol of female strength in a world steeped in religious judgment and magical menace.

Ultimately, her transformation from mortal to something other—undead yet empowered—cements her as a heroine willing to embrace darkness to redefine her own myth.

Jean Luc

Jean Luc is a character defined by contradiction—chivalrous yet condescending, loyal yet secretive, loving yet controlling. As Célie’s fiancé and Chasseur captain, he occupies a role of protector, though his attempts to shield her often undermine her autonomy and reinforce the hierarchy that keeps her marginalized.

Despite claiming to admire her strength, Jean Luc consistently withholds information, makes decisions on her behalf, and aligns himself with voices that doubt her resilience. His love for Célie seems genuine, but it is laced with a paternalistic tone that stifles rather than supports.

His refusal to trust her with the truth about Babette’s murder and the broader investigation fractures their relationship irrevocably. By placing his own perception of Célie’s fragility above her proven competence, Jean Luc becomes emblematic of the very system she must escape.

Even when Célie confronts him, demanding honesty and respect, Jean Luc falters—confessing that he doesn’t see her as capable of handling the truth or protecting herself. This admission wounds Célie deeply and ultimately propels her away from him.

Though not portrayed as malicious, Jean Luc’s inability to evolve with Célie marks him as a cautionary figure—well-intentioned but complicit in a broader structure of suppression.

Michal

Michal, the enigmatic vampire with a past steeped in loss and betrayal, enters Célie’s life as both an antagonist and an unlikely ally. His initial encounters with her are cold, laced with mockery and superiority, but beneath this façade lies a man bound by grief, particularly over his sister Mila and cousin Dimitri.

As their tenuous alliance grows, Michal’s emotional complexities are slowly unveiled. He is a creature of contradiction—capable of ruthless violence yet moved by flashes of tenderness and shared pain.

His manipulation of Célie through threats and withheld items like her engagement ring reveals his instinct for control, but his protection of her during their flight and investigation softens these edges.

Their shared experiences—from sleeping in coffins to confronting the necromancer—create a strange intimacy between them, one that blends fear with longing. Michal becomes a mirror for Célie, reflecting her darkest fears and desires, especially in their dream-like astral projections.

His brutal execution of vampires, however, unsettles Célie, forcing her to confront the shades of morality in their quest for justice. In the final chapters, when he risks his life to save her and pulls himself from the sea to fight Frederic, Michal transcends his monstrous image.

By the end, as Célie awakens in a new, undead form, her bond with Michal suggests a future forged not from fairy tales, but from mutual survival and shadowed truth.

Frederic

Frederic embodies the tragic horror of unrequited love twisted into madness. Once a friend of Célie’s and a respected figure among the Chasseurs, he devolves into the monstrous necromancer driven by an obsession with Filippa and their lost child, Frostine.

His transformation is one of the most dramatic in The Scarlet Veil, as he moves from a figure of institutional trust to one of intimate betrayal. Frederic’s actions are rooted in grief, but his methods—murder, manipulation, and resurrection magic—turn him into a gothic villain whose affection manifests as violence.

His confrontation with Célie is charged with emotional and symbolic weight. He envisions her as both a vessel and a sacrifice, reducing her to a means for restoring what he’s lost.

His affection is not for Célie herself, but for what she represents—a living link to Filippa and Frostine. His final acts, drugging her and attempting a blood ritual, underscore the depth of his delusion.

Yet there is a pathos to Frederic, as he clings to the belief that love can defy death. His downfall comes not through a grand epiphany but in a flurry of blood, magic, and refusal to let go.

He is a cautionary figure of what happens when mourning curdles into madness.

Filippa

Filippa, though largely present in memory and vision, casts a long shadow across the novel. As Célie’s older sister, she represents both an ideal and a source of trauma.

Her childhood strength and clarity become a model for Célie, yet her death, resurrection, and lingering influence complicate that image. Filippa’s symbolic appearances—especially in dreams and mystical encounters—underscore unresolved grief and the weight of expectation.

The apple’s vision revealing her as the original owner of the silver cross deepens the mystery of her story, making her both a spiritual and narrative anchor.

When her body is discovered in the magical islet, preserved in a blood-sigil-marked coffin, Filippa transforms from myth to reality. Her disfigured corpse, her past relationship with Frederic, and the possibility of her return blur the line between the sacred and the profane.

She is no longer just Célie’s memory or moral compass—she becomes a haunting reminder of the dangers of misplaced faith and the cost of forbidden love. Filippa embodies the themes of legacy, sacrifice, and the lingering power of familial bonds even in death.

Lou and Coco

Lou and Coco provide emotional ballast to Célie’s journey. Their presence offers not only comfort but confrontation—challenging her to rise above her self-doubt and reminding her of her accomplishments.

Lou, ever the voice of strength and directness, refuses to let Célie wallow in perceived weakness. She acknowledges the darkness that surrounds them, but insists that Célie has already proven her resilience.

Coco, gentler yet no less fierce, brings a maternal warmth and spiritual grounding, particularly as a witch accused and hunted.

Together, they form a sisterhood that defies bloodlines—one based on shared suffering, survival, and love. Their reunion with Célie in Requiem rekindles this bond, and their intervention during the final battle underscores the power of found family.

They do not try to rescue Célie from herself but remind her of who she already is. They are not just side characters—they are witnesses to her transformation and defenders of her agency, ensuring that she does not face the veil alone.

Dimitri and Mila

Dimitri and Mila serve as echoes of the broader vampiric tragedy embedded in the narrative. Mila’s death and vampiric resurrection ignite the mystery, and her fragmented memories serve as a key plot device to unveil deeper dangers.

Her love for her brother Michal and her doomed mission to heal Dimitri speak to her courage and naivety. Dimitri, plagued by uncontrollable bloodlust, personifies the fine line between humanity and monstrosity.

His descent into madness and eventual menace in the final battle frame him as both victim and villain.

These two characters, though peripheral, illustrate the moral ambiguity that permeates The Scarlet Veil. Their fates warn of the dangers of unchecked emotion, the cost of survival, and the blurred line between healing and harm.

Through their stories, Célie learns that not all darkness is evil, and not all love saves.

Themes

Feminine Strength and Institutional Oppression

Célie’s journey in The Scarlet Veil powerfully captures the enduring tension between female strength and patriarchal systems designed to minimize it. From the beginning, her placement among the Chasseurs is treated not as a triumph but as a curiosity or inconvenience.

Her male peers, especially Frederic, openly undermine her, while Jean Luc’s quiet paternalism masks his deeper inability to view her as an equal. These interactions are not simply individual instances of sexism; they reveal a broader societal resistance to female autonomy, particularly in institutions like the church and its militant arm.

Even Célie’s accomplishments are sabotaged or turned into hollow victories, such as when Jean Luc rigs her mission for the sake of her pride. Her identity is constantly split—fiancée, soldier, sister, survivor—yet none of these roles grant her full respect or control.

This conflict reaches its emotional apex when Célie discovers that her exclusion is not just passive ignorance but a conscious decision by those she loves to shelter and silence her. Her strength is recognized only when it is convenient or symbolic, and the moment it threatens male dominance, it is labeled as emotional, unstable, or dangerous.

The rituals of protection imposed on her become cages, each designed to keep her within the boundaries of acceptable femininity. By choosing to walk away from Jean Luc and the Chasseurs, Célie asserts that she refuses to be defined by male parameters of strength or virtue.

Her eventual transformation into something beyond human further disrupts the institutional narrative that to be powerful as a woman is to be a threat. In becoming more than what they allowed her to be, Célie exposes the fragile foundations of those systems and rewrites the definition of heroism and leadership.

Grief, Memory, and Emotional Inheritance

Célie’s past is steeped in unprocessed grief, and her emotional journey throughout The Scarlet Veil is as much about reckoning with memory as it is about confronting danger. The death and resurrection of her sister Filippa casts a long shadow, leaving her haunted by literal and symbolic ghosts.

Dreams of Filippa controlling her like a marionette and consuming her heart speak to unresolved trauma and a subconscious fear that the past will always have power over her present. This idea that grief distorts the self is echoed in her struggle to define her worth outside of the expectations imposed by others—be they familial, romantic, or cultural.

Grief in the novel is not a singular event but an emotional inheritance, passed through memory, guilt, and unresolved love. Whether it’s the loss of Filippa, the betrayal by Jean Luc, or the transformation of her relationships with Lou and Coco, each emotional rupture accumulates in Célie’s psyche.

Her visits to her sister’s grave and the horror of finding Babette’s corpse nearby show how closely grief is tied to fear and magic in the narrative. The recurring imagery of withered roses, empty coffins, and disfigured bodies captures the tension between what was lost and what remains, highlighting how memory can be both anchor and wound.

Even in her dreams, grief is not just an emotion—it becomes a place, a landscape she travels through in search of clarity. The islet with the glass coffin containing Filippa’s corpse is a literal representation of how her past continues to shape her reality.

Through these explorations, the novel suggests that true healing requires more than strength or endurance. It demands acknowledgment, confrontation, and ultimately transformation.

By the end, Célie’s decision to embrace a new form of existence suggests that while grief may never fully leave her, it no longer controls her. It becomes a chapter, not a cage.

Autonomy, Identity, and Self-Definition

Throughout The Scarlet Veil, Célie’s arc is driven by her desire to define herself outside of the identities others have imposed upon her. From the beginning, she is introduced as someone shaped by her relationships—sister to Filippa, fiancée to Jean Luc, subordinate to the Chasseurs, friend to Lou and Coco.

Each of these roles carries its own expectations, and much of Célie’s conflict arises from the growing awareness that these expectations do not align with her inner self. Her frustration at being infantilized, her horror at being left out of critical decisions, and her heartbreak over betrayals all stem from a singular root: the desire to be seen and treated as whole.

Her autonomy is constantly questioned. Jean Luc’s love is conditional on her compliance; the Chasseurs’ acceptance hinges on her silence.

Even Michal, with whom she forms a tenuous alliance, initially manipulates her through emotional leverage and moral ambiguity. Each of these interactions reinforces the theme that identity must be claimed, not granted.

Célie’s refusal to be a tool, a symbol, or a side character in someone else’s narrative becomes the foundation of her transformation. When she removes her engagement ring and chooses to pursue the investigation alone, it is not a moment of isolation but of empowerment.

This theme also intersects with her physical transformation. The astral projection, the silver ribbon from Michal, the vampire lore—each element of the supernatural is mirrored by internal change.

She is no longer the girl who had to be protected or patronized; she becomes someone who can chart her own course, make her own mistakes, and choose her own destiny. Even when facing death, she does not ask for rescue but meets it with purpose.

Her rebirth at the novel’s conclusion, her smile despite the cold and her heart no longer beating, is a declaration that she has finally become the author of her own story.

Love as Sacrifice, Power, and Reclamation

Love in The Scarlet Veil is not romanticized; it is interrogated, tested, and redefined. The novel presents love in its most complicated forms: protective, suffocating, redemptive, and destructive.

Célie’s relationship with Jean Luc begins as an emblem of trust and partnership, but gradually unravels to reveal its paternalistic roots. His love, though sincere, is wrapped in control and fear—he doesn’t trust her enough to be honest, and his desire to shield her comes at the cost of her autonomy.

The pain of this betrayal marks a key turning point in her understanding of love—not as something that binds but as something that can also cage.

Michal represents a darker, more enigmatic version of love. His interactions with Célie are laced with manipulation, yet also show moments of unexpected tenderness.

He respects her strength, listens to her intellect, and ultimately fights beside her. Their bond becomes one not of immediate romance but of mutual recognition and wary trust.

It reflects a love that is earned, not assumed—a relationship forged in shared pain and peril rather than societal obligation. The symbolic exchange of tokens—the silver cross, the ribbon—reinforces the shifting power dynamics between them and the tentative possibility of something more profound.

Familial love, particularly between Célie and Filippa, is perhaps the most haunting. It is marked by unresolved grief, betrayal, and longing, culminating in the sacrificial scene where Célie must fight for both her life and her sister’s memory.

Frederic’s obsession with Filippa and his twisted affection for Célie expose love’s potential for cruelty and violation. Yet even in these dark portrayals, the novel insists on love as a force worth reclaiming.

In the final battle, it is not vengeance but the memory of love—Mila’s warnings, Michal’s sacrifice, Lou’s faith—that fuels Célie. The last image of her smiling in the boat, changed and unbroken, is a quiet affirmation that love, when freed from control and expectation, can still be a source of strength.

Destiny, Prophecy, and the Choice of Becoming

The recurring theme of fate versus choice in The Scarlet Veil surfaces through visions, prophecies, and supernatural rituals that hint at a future already written. Célie’s journey is shaped by warnings—Eponine’s ominous apple of knowledge, dreamlike visions, and astral projections that unveil hidden truths.

Yet despite this seeming predestination, the novel continually emphasizes Célie’s agency in how she responds. The knowledge she gains is not a sentence but a summons to act, and her decisions define her transformation more than any foretelling.

The most striking aspect of this theme is the way prophecy interacts with identity. Célie is told she will find the killer, but not before the killer finds her.

She is warned of blood, betrayal, and loss, yet none of these predictions can account for the strength of her resolve. When faced with death and the lure of peace in the afterlife, she is given a final choice: to return or remain.

Her decision to live, even in an altered, undead form, is not framed as tragic but liberating. It shows that destiny is not about resignation but about what one dares to reclaim.

This tension between fate and freedom also manifests in other characters—Frederic’s obsession with rewriting the past through necromancy, Michal’s torment over Dimitri’s bloodlust, and Filippa’s entrapment in death. Each represents a different response to prophecy: denial, despair, and distortion.

Célie, in contrast, chooses clarity. She accepts what has happened, learns from it, and steps into a new future that she shapes herself.

Her arc affirms that while the path may be lined with shadows, the light ahead is one she chooses to walk toward—not because it was foretold, but because she made it hers.