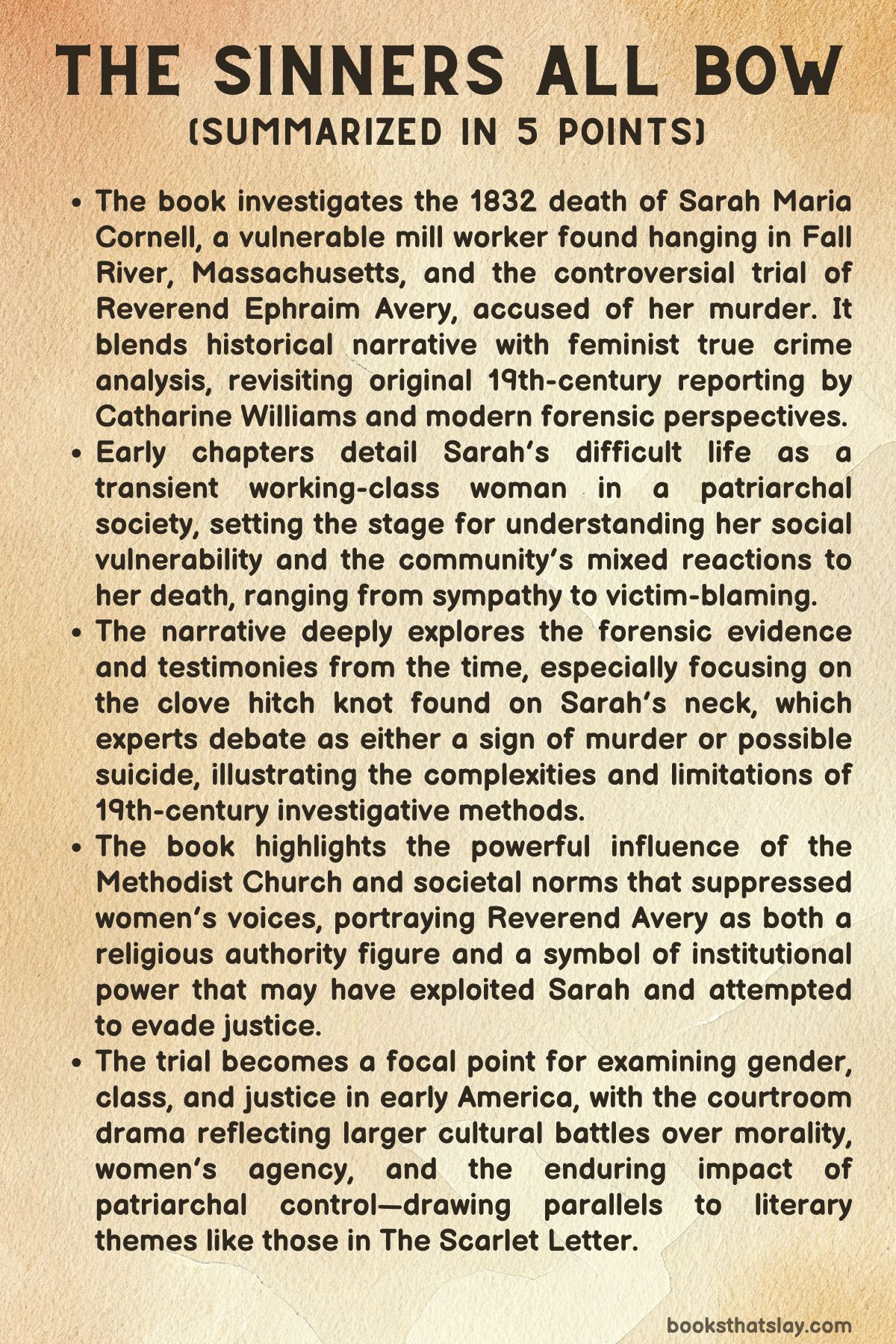

The Sinners All Bow Summary, analysis and Themes

The Sinners All Bow by Kate Winkler Dawson is a true crime narrative that bridges the past and present to reexamine the 1832 death of Sarah Maria Cornell, a young mill worker found hanged on a farm in Rhode Island. The book juxtaposes the efforts of Catharine Read Arnold Williams, a 19th-century journalist who championed Cornell’s story, with the perspective of a modern author investigating the same case.

Through detailed historical research and a modern feminist lens, the book critiques the justice system, religious institutions, and the portrayal of female victims. It’s a powerful reevaluation of an overlooked chapter in American legal and social history.

Summary

The Sinners All Bow follows the entwined investigations of two women—Catharine Read Arnold Williams, a 19th-century writer, and a present-day true crime journalist—as they attempt to uncover the truth behind the mysterious death of Sarah Maria Cornell in 1832. Though separated by nearly two centuries, both women feel a deep, personal responsibility to give voice to Sarah, a mill worker found hanging from a haystack pole on a Tiverton, Rhode Island farm.

The metaphorical collaboration between these two women shapes the structure of the book, balancing historical reconstruction with contemporary analysis.

The story begins at the site where Sarah’s body was found. Both narrators, past and present, reflect on the importance of revisiting the location of a crime to understand the victim’s experience.

Sarah’s death, initially ruled a suicide, quickly became a scandal when evidence of bruising and pregnancy emerged, pointing to foul play. Suspicion fell on Reverend Ephraim Avery, a prominent Methodist minister known to have interacted with Sarah under questionable circumstances.

Avery, a married man and former medical student, had allegedly engaged in secret meetings with Sarah and pressured her to terminate a pregnancy using a dangerous abortifacient, oil of tansy.

Catharine Williams took up Sarah’s story shortly after her death, publishing a detailed account that blamed Avery. Williams was a single mother and journalist with strong views against Methodism, which she saw as morally corrupt and socially destabilizing.

Her scathing indictment of Avery and the Methodist Church was shaped by her own life experiences—poverty, abuse, and a rigid upbringing. Despite these biases, her work represented a pioneering attempt to center the victim in a criminal narrative at a time when female victims were often dismissed or condemned.

The modern narrator recognizes the limitations in Williams’s work, especially her moral absolutism and selective compassion. Yet she also acknowledges the groundbreaking nature of Williams’s approach, which challenged a society that demonized women like Sarah.

Sarah’s background reveals the tragic decline of a woman born into a once-prominent family. Her grandfather had advised George Washington, but her mother’s marriage to a laborer and her father’s eventual abandonment left Sarah impoverished.

She drifted from factory to factory in New England, part of a growing class of female laborers whose economic independence came at great personal cost.

Sarah’s religious devotion to Methodism provided her with hope but also made her vulnerable. Methodist revivalism, popular among working-class women, was both emotionally empowering and socially controversial.

Its egalitarian appeal clashed with traditional religious hierarchies and moral standards. Sarah became deeply involved in the church, but her growing attachment to Reverend Avery led to spiritual betrayal.

As her letters later revealed, she struggled with shame, longing, and a desire for forgiveness—even as Avery maneuvered to excommunicate her and deny responsibility for her pregnancy.

After Sarah’s body was discovered, a group of women preparing her for burial noticed signs that contradicted the suicide ruling. Bruises and a pained expression suggested violence.

Forensic evidence, although primitive by today’s standards, pointed to possible strangulation rather than self-hanging. Sarah’s possession of oil of tansy raised suspicions of an attempted or forced abortion.

Her spiritual and emotional torment, combined with physical evidence, spurred calls for a deeper investigation.

Avery was arrested and released in Bristol due to insufficient evidence, only to be re-arrested when jurisdictional issues brought the case to Tiverton. The manhunt ended with Avery being found hiding in New Hampshire.

His trial in Newport was one of the most sensational in early American history. It split religious communities and drew national attention, highlighting the growing tensions between Methodists and more traditional New Englanders.

The trial itself became a battle of narratives. The prosecution leaned heavily on circumstantial evidence: letters Sarah wrote, her alleged final meeting with Avery, witness accounts of her state of mind, and the forensic inconsistencies in the suicide theory.

Witnesses described Avery’s evasive behavior and testified that he had been near the Durfee farm around the time of Sarah’s death. Sarah had reportedly written to Avery multiple times requesting absolution and asking for a certificate of moral standing—a sign she sought social redemption and did not intend to end her life.

The defense countered with character assassination. Over 150 witnesses, many of them connected to the Methodist Church, painted Sarah as manipulative, immoral, and mentally unstable.

They claimed she had threatened suicide before and used her pregnancy to extract attention or revenge. The strategy aimed to destroy Sarah’s credibility and sow doubt about Avery’s role.

Despite the prosecution’s efforts, the jury was unconvinced. Without direct evidence linking Avery to the act, he was acquitted.

Catharine Williams documented the entire case in her book Fall River, presenting it as a cautionary tale of how institutions failed to protect vulnerable women. She accused the defense of weaponizing moral judgment and argued that Sarah’s story exemplified systemic misogyny.

Though her account was biased, it was one of the earliest attempts to preserve the memory of a female victim in a system designed to erase her.

Modern forensic methods, including handwriting analysis, later suggested that Avery likely wrote the anonymous note used to lure Sarah to her final meeting—the note she believed came from a friend. Despite his legal acquittal, Avery lived the rest of his life in disgrace, overshadowed by the case.

Sarah, long dismissed as a cautionary example, has since been reinterpreted as a victim of gendered violence and religious exploitation.

The Sinners All Bow argues for a reformation in how true crime is written and consumed. It calls for compassion and accuracy over sensationalism and gossip.

The book reframes Sarah Cornell not as a fallen woman or tragic footnote, but as a fully realized human being whose life and death deserve understanding. Through the dual lens of Catharine Williams and a modern author, the book restores dignity to a forgotten victim and critiques the societal structures that failed her.

Key People

Sarah Maria Cornell

Sarah Maria Cornell stands as the tragic and emblematic center of The Sinners All Bow, a woman whose life story encapsulates the brutal injustices faced by working-class women in 19th-century America. Her life was shaped by contradiction: born into the legacy of the prestigious Leffingwell family, but cast into poverty due to her mother’s disavowal of elite expectations and a father who ultimately abandoned the family.

As a young mill worker drifting across New England’s textile towns, Sarah endured a life of instability and relentless labor. Her search for spiritual grounding and social acceptance led her to the Methodist Church, where she found both solace and betrayal.

Her devotion to religious practice was sincere, but she became the target of judgment and suspicion—ultimately manipulated by the very institution she hoped would redeem her. Her yearning for beauty and normalcy in a judgmental society caused her to make mistakes, such as stealing a dress, which further fueled her social alienation.

Sarah’s strength is evident in her continued fight for dignity—through her letters, her confrontations with church authorities, and her attempts to secure moral exoneration from Reverend Avery. Even in the face of relentless gossip, sexual coercion, and abandonment, Sarah clung to a sense of righteousness, writing letters that pleaded not just for forgiveness but for acknowledgment of her humanity.

Her death, mischaracterized by some as suicide, is ultimately revealed as a consequence of systemic misogyny, sexual exploitation, and ecclesiastical power. In death, she became a symbol of endurance and injustice, her life reclaimed by the voices who refused to let her be forgotten.

Catharine Read Arnold Williams

Catharine Williams emerges in the narrative as a fiercely intelligent, deeply emotional, and morally impassioned figure whose role in The Sinners All Bow is not merely of chronicler, but of crusader. A woman who straddled the margins of her own era, Catharine was born into privilege yet endured economic and social hardship following the death of her mother.

Raised by austere and conservative aunts, she developed a combative independence and intellectual hunger that would eventually shape her identity as a pioneering journalist and advocate. Her approach to the Sarah Cornell case was radical for the time: she viewed Sarah not as a fallen woman, but as a victim of societal neglect and predatory religion.

Her writing in Fall River exemplifies an early form of feminist journalism, daring to confront religious institutions, male authority, and cultural double standards.

Catharine’s emotional investment in Sarah’s story mirrored her own struggles with isolation and gendered injustice. She saw in Sarah a reflection of herself—abandoned, misunderstood, and desperate for justice.

Though her reporting was colored by bias and her scorn for Methodism, she ultimately provided a vital platform for the silenced. Her insistence on visiting crime scenes and gathering forensic-style evidence was groundbreaking, and her emotional prose elevated true crime writing into a moral reckoning.

Catharine’s work was not without flaws—she harbored prejudices, especially against the evangelical fervor of Methodists—but her efforts established her as a trailblazing voice in American journalism, one who dared to transform the narrative around a woman history might otherwise have erased.

Reverend Ephraim Avery

Reverend Ephraim Avery stands as the antagonist of The Sinners All Bow, a man whose public persona as a devout Methodist minister starkly contrasts with the secretive, coercive, and ultimately abusive behaviors attributed to him. Educated and once a medical student, Avery occupied a powerful position within the burgeoning Methodist movement—a denomination that promised moral and spiritual rejuvenation but also wielded tight control over its members.

His relationship with Sarah began under the guise of pastoral care but quickly turned sinister. He was a man who knew the rules and used them to his advantage: encouraging Sarah’s participation in camp meetings while simultaneously arranging her excommunication, suggesting abortifacients like oil of tansy while refusing to take public responsibility for her pregnancy, and manipulating his religious authority to isolate and silence her.

Avery’s trial strategy relied heavily on character assassination and institutional solidarity. Despite damning circumstantial evidence—including testimonies about his late-night visits, inconsistencies in his alibi, and suggestions that he authored the letter luring Sarah to her death—he was shielded by a legal system deeply sympathetic to his station.

His defense relied on vilifying Sarah as unstable, immoral, and vindictive. Avery’s acquittal reflected not innocence, but the failure of a society and a justice system to protect women like Sarah.

Though he avoided legal punishment, he remained haunted by public suspicion, his career and reputation forever tarnished. Avery personifies the dangers of unchecked institutional power—particularly when fused with gendered authority—and serves as a chilling example of how faith can be weaponized against the vulnerable.

The Narrator (Modern-Day True Crime Journalist)

The unnamed modern journalist in The Sinners All Bow serves as both investigator and interpreter, bridging the temporal gap between Catharine Williams’s 19th-century advocacy and contemporary understandings of justice, victimhood, and narrative authority. Her presence is not passive; she embodies a new genre of true crime—one rooted in victimology, forensic science, and moral clarity.

Like Catharine, she is a single mother and a writer, but she brings the tools of modern criminology to a case long settled in historical record. Her emotional identification with Sarah and Catharine creates a thematic throughline: women across time who seek truth not only in data, but in the lived emotional realities of the forgotten.

Her investigation questions Williams’s assumptions, confronts the limits of 19th-century reporting, and insists on a deeper, more nuanced portrayal of Sarah—not simply as a symbol, but as a whole person. She brings attention to the cultural and institutional forces that shape both the crime and its coverage: gender, class, labor exploitation, and religious manipulation.

Through her, the narrative gains a contemporary urgency. She is both scholar and witness, offering readers a model of what empathetic, rigorous true crime storytelling can be.

In honoring Sarah while critiquing past missteps, the narrator carves out space for justice that is both retrospective and redemptive.

John Durfee

John Durfee, the man who discovered Sarah Cornell’s body, occupies a quieter but crucial role in The Sinners All Bow. A member of the prominent Durfee family, he represents a rare embodiment of reliability and compassion in a community swirling with suspicion and gossip.

Unlike others in the story whose testimonies were marred by judgment or evasiveness, John’s account is presented with clarity and care. He walked the crime scene with attention to detail, his memory forming the basis for later forensic reconstructions of the scene.

His observations—about the rope, the position of the body, the lack of disturbance nearby—lent credence to the growing belief that Sarah’s death was not a suicide.

Though a product of Fall River’s elite class, John Durfee did not exploit his position to manipulate the case. Instead, his understated role as a witness helped anchor the early stages of the investigation in empirical detail rather than rumor or religious fervor.

His compassion stands in stark contrast to the many others—especially within the Methodist community—who sought to distance themselves from Sarah and cast aspersions on her character. Durfee’s presence in the narrative thus underscores the importance of honest, impartial testimony in a case defined by ideological warfare and social prejudice.

Harriet Hathaway

Harriet Hathaway, Sarah’s boardinghouse matron, provides one of the most emotionally resonant perspectives in The Sinners All Bow. As the woman who housed Sarah in her final days, Harriet bore witness to her emotional state, daily routines, and fears.

Her recollections, and those of her daughter, directly challenged the narrative of suicide propagated by Avery’s defense. They described Sarah as purposeful, composed, and hopeful about resolving her situation, even as she prepared for a secretive meeting on the night she died.

Harriet’s testimony became essential in shaping a portrait of Sarah as a victim, not of despair, but of deception. By affirming Sarah’s careful dress, her behavior, and her final words, Harriet humanized a woman too often flattened into a cautionary tale or moral parable.

She represented the everyday women—those without power or platforms—whose small acts of honesty helped combat an overwhelming tide of institutional denial. Her role in the narrative adds warmth, gravity, and moral clarity to a story fraught with ideological conflict and public spectacle.

Themes

Gendered Injustice and the Stigma of Female Sexuality

The life and death of Sarah Maria Cornell are underscored by a persistent and brutal scrutiny of female sexuality within a patriarchal framework. Throughout The Sinners All Bow, the perception of Sarah’s moral character is weaponized against her, both during her life and posthumously.

After being impregnated by Reverend Ephraim Avery and subsequently found dead, Sarah becomes the subject of both religious and judicial scrutiny, where the focus often drifts from the crime itself to her sexual behavior and reputation. Despite being the victim of what appears to be rape and murder, Sarah is repeatedly portrayed by Avery’s defense and the broader Methodist community as promiscuous, mentally unstable, and deceitful.

The defense enlists over 150 witnesses to suggest that Sarah’s character is evidence enough to doubt her credibility and assume she may have orchestrated her own death out of desperation or revenge. This tactic shifts attention from the accused to the victim, exposing how women’s bodies and choices are surveilled, judged, and ultimately used against them.

Even in death, Sarah is not allowed the dignity of innocence or neutrality. Her pregnancy becomes a scandal, not a tragedy, and her plea for forgiveness—a deeply spiritual act—is reframed as manipulative or hysterical.

The trial serves not only as a judicial proceeding but as a social inquisition into a woman’s worth. The narrative reveals how easily a woman could be silenced and discarded if her moral conduct did not align with societal expectations.

Sarah’s letters, full of yearning for absolution, highlight how deeply she internalized the shame imposed upon her. Catharine Williams’s insistence on Sarah’s virtue, though itself not free from bias, challenges this prevailing framework and attempts to restore some measure of agency and dignity to Sarah.

But even Williams’s portrait of Sarah is idealized, filtering her complexity through the lens of virtue rather than allowing her the full scope of flawed humanity. The theme ultimately underscores a historical pattern wherein female sexuality was not only policed but used to justify violence and erase accountability.

Institutional Complicity and Religious Hypocrisy

The Methodist Church and broader religious structures are portrayed in The Sinners All Bow as deeply complicit in Sarah Cornell’s suffering and death. Reverend Avery, a powerful figure within the Methodist community, is not just accused of sexual misconduct and murder—he represents the dangers of unchecked institutional authority.

His actions—grooming Sarah under the guise of spiritual counsel, encouraging the use of abortifacients, excommunicating her in secret, and ultimately abandoning her—are shielded by the very organization that claims to uphold moral and spiritual righteousness. Rather than confronting Avery’s transgressions, the Church protects him, providing legal resources, orchestrating character attacks against Sarah, and ensuring his acquittal despite overwhelming circumstantial evidence.

This institutional defense of Avery reveals the extent to which religious organizations prioritize their reputation and internal hierarchies over the pursuit of justice.

Moreover, the Methodist Church’s stance toward factory girls like Sarah is fraught with contradictions. While preaching redemption and inclusivity, it simultaneously ostracizes women whose behavior fails to meet their moral standards, regardless of the context.

The evangelical fervor and emotionalism of Methodist revivals attract marginalized women with promises of belonging, but this inclusion is conditional and fragile. Sarah, after being excommunicated and rejected, continues to seek forgiveness within this very system, underscoring how institutional betrayal is compounded by spiritual dependence.

The narrative uses this tension to critique religious hypocrisy—not just in doctrine but in practice—highlighting how institutions often enable and obscure violence committed by their representatives. The Church’s ability to shape public opinion, legal outcomes, and even the memory of its victims reveals the profound power it holds and its willingness to abuse it to preserve its authority.

Class, Labor, and Social Marginalization

Sarah Cornell’s story cannot be disentangled from the economic and class dynamics of early 19th-century New England. As a mill worker in towns like Fall River, she represents a growing class of women who sought financial independence through industrial labor but found themselves caught in a system that devalued their autonomy and subjected them to exploitative conditions.

The textile mills, though offering wages, demanded grueling labor and placed women like Sarah under constant moral surveillance. Any deviation from expected behavior—whether in appearance, speech, or associations—could result in social ostracization or job loss.

Sarah’s brief episode of theft, despite her repentance, shadows her permanently, illustrating how working-class women were afforded little room for error.

Her desire for stability and beauty, evident in her yearning for fashionable clothing and personal dignity, clashes with the rigid expectations imposed on poor women. Unlike her privileged ancestors, Sarah has no social cushion, and every misstep carries severe consequences.

Her mobility from town to town in search of employment underscores the instability of her life. Her marginal status makes her both vulnerable to predators like Avery and defenseless against the moralizing judgments of society.

Her background also contrasts sharply with that of Catharine Williams, who, despite her own hardships, occupies a more empowered social position. Catharine can write, publish, and influence public opinion—privileges Sarah never had.

The narrative uses Sarah’s life to expose how the intersection of gender and class magnifies vulnerability. Her death is not just a singular tragedy but a systemic failure, emblematic of how laboring women were used, discarded, and often blamed for their own exploitation.

Even her burial and legacy are shaped by class distinctions; while her advocates fight to preserve her dignity, institutions and elites attempt to erase or discredit her. The story reminds readers that justice was—and often still is—a privilege more easily afforded to the socially and economically powerful.

Memory, Advocacy, and the Ethics of Storytelling

Through the parallel narratives of Catharine Williams and the modern journalist narrator, The Sinners All Bow interrogates the ethics of storytelling, particularly in the true crime genre. Catharine’s decision to tell Sarah’s story in Fall River was pioneering; she refused to accept the official account of suicide and offered a counter-narrative centered on Sarah’s humanity and the likelihood of murder.

Yet, her motivations were not purely objective. Her disdain for Methodism and her zeal for moral clarity colored her portrayal of Avery as irredeemably villainous and Sarah as a sanctified victim.

The modern narrator, aware of these limitations, scrutinizes Catharine’s biases while still valuing her commitment to giving voice to a marginalized woman.

This dual lens challenges the conventions of true crime storytelling, where victims are often reduced to footnotes or sensationalized for entertainment. The book emphasizes the responsibility of storytellers to honor the lives of victims—not just their deaths—and to resist the temptation to mold narratives around ideological or emotional certainties.

It also reflects on how memory is shaped by who gets to tell the story and which details are preserved or omitted. Catharine’s advocacy ensured that Sarah’s name did not vanish into obscurity, but it also shaped her memory through a specific moral framework.

The modern narrator’s engagement with Sarah’s life is marked by caution and reverence. By revisiting crime scenes, examining historical records, and confronting uncomfortable truths—including Catharine’s own failings—she models a more nuanced, ethical approach to storytelling.

This theme reinforces the importance of historical accuracy, emotional sensitivity, and narrative restraint. It also raises uncomfortable questions: can we ever fully know a victim?

And what do we owe them in our retellings?

In confronting these questions, the book offers not just a crime story, but a meditation on the ethics of remembrance and the power of narrative to either obscure or illuminate truth.