The Snow Angel Summary, Characters and Themes

The Snow Angel by Anki Edvinsson is a Nordic crime thriller set in the icy town of Umeå, Sweden.

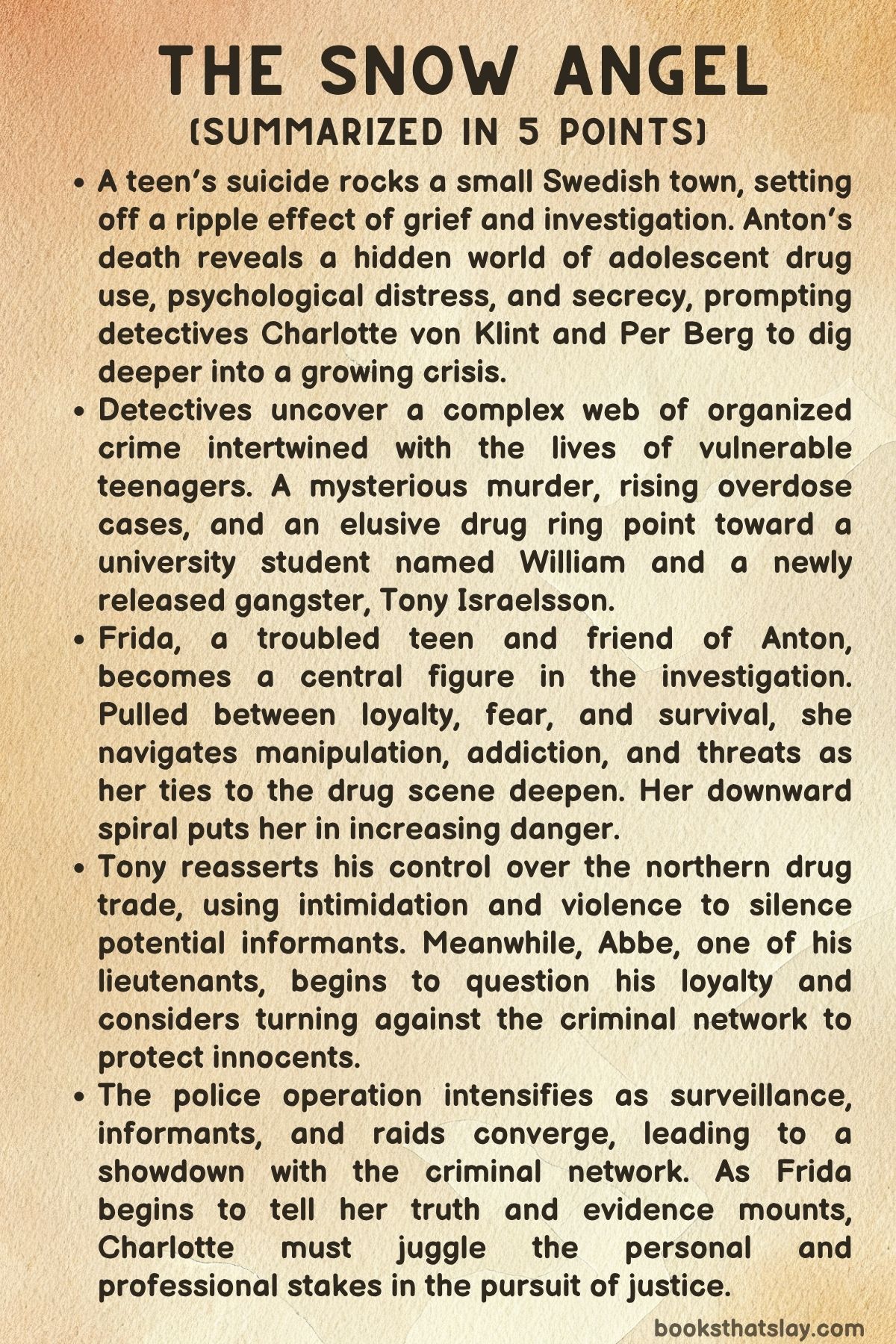

The novel blends a gripping police procedural with a deeply human story about trauma, youth, and crime. At its heart is detective Charlotte von Klint, balancing her professional duties with personal struggles, as she investigates a suicide and a string of violent crimes. What begins as a local tragedy slowly reveals a much wider network of drug trafficking, exploitation, and buried secrets. With a fast pace and emotional depth, the story explores how vulnerable teens are drawn into dangerous worlds.

Summary

The story begins with the suicide of Anton, a troubled teenager in Umeå. On a freezing night in January, he jumps off a bridge in front of his horrified parents.

His death sends ripples through the community, raising questions about what led to his despair. Simultaneously, detective Charlotte von Klint and her daughter Anja are planning a move, seeking stability after a difficult divorce.

Charlotte is soon pulled into the investigation of a murdered woman named Unni Olofsson. She is found strangled in her bathtub in what appears to be a staged crime scene.

Unni’s background as a youth advocate with social services hints that her work may have made her a target. As Charlotte and her colleague Per dig into the case, they uncover a pattern of teen drug abuse linked to tramadol.

There is a growing sense of unease in the town. Charlotte’s instincts lead her to consider connections between Anton’s death, Unni’s murder, and local drug activity.

Meanwhile, Tony Israelsson, a recently released criminal, arrives in Umeå to rebuild his drug network. He brings with him Abbe, a conflicted associate.

Tony sets his sights on eliminating anyone who could threaten his plans — including Viggo, a man in hiding under a new identity. Viggo’s daughter, Frida, becomes a central figure as she navigates grief over Anton’s death.

She also struggles with her own drug use and a coercive relationship with William, a university student and key figure in the local drug trade. Frida’s descent is troubling.

She parties at the notorious Nydala house, where drugs and manipulation are rampant. William pressures her and other teens into risky behavior, and Frida struggles with shame and fear.

Linn, Frida’s friend, discovers disturbing content on her phone linking William to criminal acts. As tensions rise at school and suspicions mount, Charlotte and Per begin to close in on William and his operation.

Abbe, increasingly disillusioned with Tony’s brutality, contacts the police and begins cooperating. His information confirms the links between Tony’s network, William’s drug ring, and the string of teen overdoses and deaths.

As police surveillance ramps up, the Nydala house becomes the center of the investigation. A major turning point arrives when police raid a party at the Nydala house.

William is arrested, and Frida is taken in, traumatized but alive. Her testimony is crucial.

She confirms William supplied drugs to Anton and details how she was manipulated. This gives law enforcement the leverage they need to prosecute both William and Tony.

Tony, sensing the net closing, becomes increasingly violent. He attempts to flee and abduct Frida.

But he is thwarted thanks to Abbe’s warning and quick police intervention. Tony is captured in a remote cabin, ending his reign of fear.

In the aftermath, Frida begins rehabilitation with the support of her father. Charlotte considers the personal cost of her work.

But she recommits to staying in Umeå, recognizing how vital her presence is. Her relationship with Anja improves, symbolizing a step toward healing.

The book ends with a memorial for Anton. Charlotte and Per stand with his family and classmates.

It’s a quiet but powerful tribute, reminding the community of the lasting impact of silence, trauma, and neglect. The case is closed, but the scars remain — and the need for change is clear.

Characters

Charlotte von Klint

Charlotte von Klint is the novel’s central detective, but her strength lies not only in her professional competence but in the personal layers that shape her. She is a single mother, recently divorced, juggling the emotional weight of raising a daughter with the psychological demands of homicide investigations.

Her interactions with Anja reflect the strain of a career in law enforcement that often isolates her from emotional closeness. Yet they also reveal a fierce maternal protectiveness and longing for connection.

Charlotte carries past trauma and present stress with a stoic resilience. But moments of introspection and vulnerability—especially concerning the young victims like Anton and Frida—underscore her depth and empathy.

Her character evolves from a distant, duty-bound investigator into someone who finds renewed purpose in protecting youth and confronting systemic violence.

Frida

Frida is one of the most emotionally complex characters in the story. She is a teenager caught at the intersection of trauma, manipulation, and guilt.

Initially introduced as a typical troubled youth experimenting with drugs, her journey reveals a young girl spiraling into self-destruction due to external pressure and internal grief. Her relationship with William starts as one of infatuation but quickly becomes a symbol of coercion and exploitation.

Frida’s guilt over Anton’s death, compounded by her involvement in criminal activities, eats away at her. Her descent is as much about psychological isolation as it is about substance abuse.

However, her arc is ultimately redemptive. Her testimony against William, her willingness to confront the truth, and her entry into rehab reflect a painful but hopeful path toward healing.

Frida embodies the collateral damage of criminal networks and the quiet strength it takes to survive them.

Anton

Anton’s character, though his presence in the novel is brief, is profoundly impactful. His suicide is the emotional and narrative catalyst for much of the book’s action.

Through others’ recollections, we see a portrait of a sensitive, intelligent boy overwhelmed by inner darkness. His compulsive behaviors and social withdrawal hint at deeper mental health struggles exacerbated by exposure to drugs and perhaps knowledge of dangerous secrets.

Anton represents the unseen victims in society—the ones who suffer quietly until it’s too late. His legacy in the story is not just one of tragedy but one that forces others to face uncomfortable truths.

Tony Israelsson

Tony is the embodiment of the criminal underworld’s calculating ruthlessness. As the leader of the syndicate, recently released from prison, he returns with a chilling focus on revenge, control, and expansion.

His cruelty escalates throughout the novel, culminating in orders to kill and an attempted abduction. Tony is not just a criminal; he is a manipulative predator who thrives on fear and dominance.

What makes him particularly dangerous is his personal vendetta against Viggo. This vendetta drags Frida into deeper peril.

His arrest signals the collapse of the old guard of organized crime. Yet his shadow lingers as a reminder of how far-reaching and personal such violence can become.

William

William is a disturbing portrayal of a predator operating under the guise of a charismatic student. At first, he appears as just another young man within Umeå’s social circles, but his true nature emerges as someone exploiting vulnerable teens for personal gain.

His relationship with Frida is not just manipulative—it is emblematic of grooming and emotional abuse. William’s paranoia and eventual downfall are indicative of a man who knew the risk of exposure, yet continued exploiting others for power and profit.

His arrest and the evidence against him provide a grim but necessary confrontation with the dangers that can lurk within supposedly ordinary environments like schools and parties.

Abbe

Abbe’s journey is one of reluctant redemption. As Tony’s right-hand man, he is complicit in violence and crime, yet he is also the first to question the path they are on.

Witnessing the increasing brutality, especially when it begins to threaten civilians and teenagers, shakes his loyalty. His eventual decision to become an informant is not framed as heroic but human—motivated by guilt, fear, and a desire to prevent further harm.

Abbe’s insider knowledge is crucial in dismantling Tony’s operation. His arc reflects the nuanced moral gray zones of those trapped in criminal systems.

Per Berg

Per, Charlotte’s investigative partner, plays a stabilizing role throughout the narrative. He is competent, dependable, and offers a grounding presence in a chaotic investigation.

While not deeply explored emotionally compared to Charlotte, his consistent support and investigative intuition make him a valuable counterpart. His quiet diligence complements Charlotte’s emotional complexity.

Per’s presence reinforces the theme of teamwork and trust in the face of a society unraveling at the seams.

Viggo

Viggo, Frida’s father, is a man haunted by the past and terrified of its return. Once connected to Tony’s world, he now lives in constant fear of exposure, which paralyzes him from confronting Frida’s descent.

His love for his daughter is evident, yet his silence and passivity make him a tragic figure—someone who chose safety over confrontation until it was nearly too late. Still, his eventual support for Frida’s recovery and his attempts to help shield her from further harm mark a quiet redemption arc.

Viggo represents the long shadows of past choices and the difficult road toward making amends.

Anja

Anja, Charlotte’s daughter, has a smaller but significant role. She symbolizes the personal life Charlotte struggles to protect amidst professional chaos.

Their bond is strained by years of distance and secrets. But as the narrative unfolds, Anja becomes a subtle moral compass for her mother.

Their final reconciliation suggests hope—that amidst institutional failure and personal trauma, human connection can still thrive. Anja’s presence brings warmth to an otherwise grim narrative, showing that even amid darkness, there’s a place for understanding and renewal.

Themes

Teenage Vulnerability and Mental Health

The novel paints a haunting and empathetic portrait of teenage fragility, starting with Anton’s suicide in the opening chapters. His internal suffering—characterized by compulsive thoughts, despair, and isolation—is not an isolated incident but rather the symptom of a larger, pervasive issue among the youth in Umeå.

Frida’s descent into substance abuse and self-destructive behavior continues this thread. It shows how trauma, loneliness, and manipulation can push young people into dangerous corners.

The pressures teens face—both internally and externally—are not always visible to the adults around them. Teachers, parents, and even law enforcement often only catch glimpses of the damage after it has escalated beyond control.

Anton’s suicide becomes a silent alarm for the community, yet even then, the responses feel delayed and incomplete. The narrative insists that mental health crises don’t arise in a vacuum.

They’re rooted in relationships, societal expectations, familial legacies, and the systemic failure to provide early support. By following multiple teen characters and their struggles, The Snow Angel creates a deeply affecting commentary on the invisible battles many adolescents endure daily.

The story does not romanticize pain. It spotlights the sheer urgency with which communities must respond to young people teetering on the edge.

Frida’s eventual commitment to therapy offers a glimmer of hope. But it also underscores how late intervention often is, and how much suffering has to unfold before help arrives.

This theme is not only about mental health itself but about the collective denial or ineffectiveness that surrounds it.

Organized Crime and the Corruption of Innocence

Throughout the novel, organized crime serves not just as a backdrop but as a corrosive force that infiltrates the lives of both the vulnerable and the powerful. Tony Israelsson’s network is not merely composed of hardened criminals—it thrives by exploiting youth.

It manipulates those who are lonely, impoverished, or emotionally unstable. The criminal underworld depicted in the book doesn’t arrive with obvious threats but with parties, charm, peer pressure, and promises of belonging.

William, a university student, represents a particularly disturbing face of this operation. He operates within the social scene of teens and young adults, blurring the line between peer and predator.

His grooming tactics, exploitative control over Frida, and orchestrated presence at parties where drugs flow freely show how criminal systems adapt to target the most impressionable. The violence in this world isn’t always physical—sometimes it’s psychological, emotional, and long-lasting.

Tony’s reach even into witness-protected lives like Viggo’s shows how deep and persistent this criminal grip is. What’s particularly harrowing is how normalized danger becomes for some characters, especially the youth.

The casualness with which drugs are exchanged, the quiet compliance to abuse, and the hesitancy of bystanders like Linn to speak up highlight the chilling effectiveness of fear and manipulation. Ultimately, The Snow Angel does not glamorize crime.

It portrays it as decay—of how innocence is eroded, trust is weaponized, and entire communities are destabilized by a cancer that grows quietly and often invisibly.

Justice, Law Enforcement, and Moral Complexity

The novel explores the limitations and emotional toll of justice through the lens of Charlotte von Klint and her colleagues. As detectives, Charlotte and Per are not infallible heroes, but people navigating a deeply broken system.

Their work is tedious, emotionally draining, and morally complex. The process of gathering evidence, chasing suspects, and protecting victims is not a clean arc of good triumphing over evil.

Instead, it is a layered, ambiguous pursuit in which victories come at great personal and communal cost. Charlotte, in particular, struggles to reconcile her professional identity with her personal life.

Her role as a mother is constantly in tension with her responsibilities as a detective. She is burdened by guilt and driven by empathy, especially when cases involve youth.

The book doesn’t let law enforcement off the hook for its shortcomings. It portrays the police force as human—limited, overworked, and often arriving too late.

The use of informants like Abbe introduces another layer of moral complication. Abbe’s transformation from loyal lieutenant to whistleblower forces readers to question redemption, loyalty, and survival.

Can someone who has enabled destruction truly find redemption through a single act of truth-telling? Similarly, Frida’s decision to cooperate with police opens questions about victimhood and agency.

Her testimony is crucial, but it’s also painful and slow. Justice in The Snow Angel isn’t swift or satisfying.

It’s messy, emotionally charged, and rarely complete. Yet, the novel suggests that flawed, determined efforts are still vital, even if imperfect.

Family, Trauma, and Generational Cycles

Family relationships in The Snow Angel are presented as both sources of pain and potential salvation. Frida and her father Viggo are perhaps the clearest example of a family dynamic shaped by fear and silence.

Viggo, once involved with Tony’s criminal world, tries to shield Frida by withdrawing emotionally. His past decisions cast a long shadow over his ability to parent, even though his intentions are protective.

His silence becomes a prison for both of them. Frida, feeling abandoned and misunderstood, seeks validation elsewhere, walking straight into the arms of exploitative figures like William.

The novel shows how trauma is often passed down not through words but through absence, tension, and unresolved histories. Charlotte and her daughter Anja represent a contrasting dynamic.

Their relationship is strained by Charlotte’s demanding job and past divorce, yet it ultimately trends toward healing. When Anja finally expresses pride in her mother, it’s a breakthrough moment.

It illustrates how open communication and vulnerability can begin to mend familial rifts. These family stories emphasize how emotional neglect—whether caused by trauma, career focus, or fear—creates voids that children instinctively try to fill.

The book implies that to break generational cycles, families must face their histories directly. They must learn to speak about pain before it metastasizes into tragedy.

This theme underpins the novel’s emotional center. Behind every addict, every victim, every criminal, there is often a family wrestling with what they did or failed to do.

Loss, Grief, and the Long Road to Healing

From the first chapter to the last, grief permeates the narrative. Anton’s suicide casts a long and chilling shadow over nearly every event in the book.

His death becomes a haunting presence, not just in the lives of his parents and friends, but in the broader community struggling to make sense of why a young life ended so tragically. Grief in this novel is not portrayed as a linear process.

It is chaotic, it alienates, and it transforms people in unanticipated ways. For Frida, grief mutates into self-loathing and reckless behavior.

For Linn, it becomes a moral awakening. For Charlotte, it intensifies her resolve but also exposes her vulnerabilities.

The novel acknowledges that there is no single right way to grieve. Nor does it suggest that grief can be easily resolved.

Even in its final chapters, healing is tentative and slow. Frida’s entrance into rehab is not framed as a triumphant moment, but a fragile beginning.

The community memorial for Anton is touching but also bittersweet. It reminds readers that closure doesn’t erase pain—it merely allows space for it.

The Snow Angel ultimately proposes that healing requires both individual courage and collective support. It is not a matter of forgetting or moving on, but of carrying forward a new understanding shaped by loss.

In this way, the book offers a sobering but compassionate look at how human beings carry grief. Sometimes the most heroic thing a person can do is simply continue.