The Starlets Summary, Characters and Themes | Lee Kelly and Jennifer Thorne

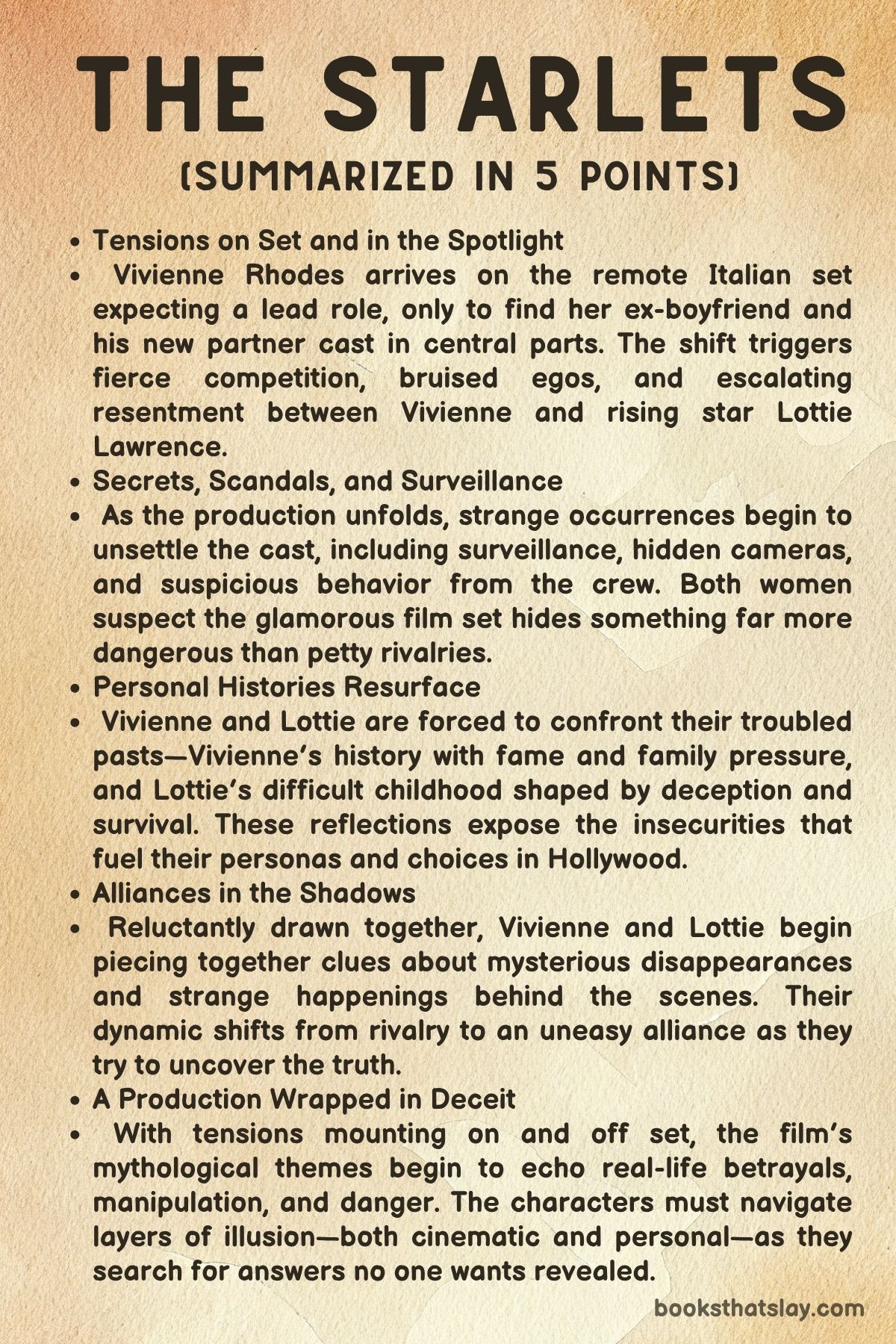

The Starlets by Lee Kelly and Jennifer Thorne is a thrilling, character-driven novel set against the dazzling yet deceptive backdrop of 1950s Hollywood and Europe.

What begins as a story about rival actresses vying for stardom soon escalates into a high-stakes escapade involving international crime, hidden agendas, and a fight for survival. Through the lens of Vivienne Rhodes and Lottie Lawrence—two women with vastly different pasts but intertwined fates—the book explores ambition, betrayal, reinvention, and the grit required to rewrite one’s own narrative. With glamour and danger in equal measure, The Starlets is a cinematic adventure about truth, trust, and unexpected solidarity.

Summary

The story opens on the remote Italian island of Tavalli, where the production of A Thousand Ships is underway.

Vivienne Rhodes, a seasoned Hollywood actress, arrives believing she has secured the role of Helen of Troy—an iconic part that could elevate her from respected performer to full-fledged star. But her arrival brings humiliation: the role of Helen has gone to her rival, Lottie Lawrence, a younger actress with a sugary teen-idol image.

Vivienne is instead cast as Cassandra, the doomed seer, a role she finds insulting. Her fury is heightened by the presence of Teddy Walters—her former lover—who is now romantically involved with Lottie.

Their breakup, which had begun as a publicity stunt, had grown real for Vivienne, making the betrayal cut even deeper.

Apex Pictures’ new head, Jack Gallo, tries to assuage Vivienne’s pride by emphasizing Cassandra’s creative potential and offering her some control over the role. Though hesitant, Vivienne remains, deciding to transform the marginal character into a powerful statement.

She demands rewrites and creative freedom, asserting herself against the production’s director, Sydney Durand, and the screenwriter, Max Montrose.

Max, working in secret due to blacklisting, is already navigating complications: he’s rewriting the script unofficially, romantically involved with Teddy, and suspicious of Gallo’s true motivations.

Meanwhile, Lottie is privately overwhelmed by the pressure of proving herself a serious actress. Still living under the shadow of her early fame and desperate to reinvent her image, she clings to Teddy for stability and to Max for creative credibility.

But as the production teeters on chaos—due to the mysterious disappearance of former producer William Wagner and eerie behavior from the locals involved in building the massive Trojan Horse prop—both women begin to sense that something is not right on set.

Vivienne and Lottie clash repeatedly, their interactions charged by past grievances and current insecurities. Yet the underlying tension of the production grows more sinister.

While exploring the island, Lottie stumbles upon a hidden cove filled with rotting props and a corpse. She barely escapes a group of armed men led by Ludovico, the prop master, who seems to be overseeing an illicit operation beneath the guise of filmmaking.

At the same time, Vivienne’s romantic dinner with Gallo aboard his yacht turns deadly when an extra reveals himself to be an Interpol agent. Shot mid-sentence, he collapses into her arms, slipping her a film canister and warning her of a threat before dying.

Vivienne escapes by diving into the water, and by coincidence, Lottie arrives in a stolen boat to rescue her. Now fugitives, the two women are forced into an uneasy alliance.

They flee to Monaco with the film canister, believing it may hold the key to uncovering the conspiracy behind the production.

In Monaco, they encounter further danger, including corrupt police and dead ends in seeking help. Even Lottie’s supposed connections to Princess Grace fall apart.

Their plan shifts from public exposure to covert survival. Lottie taps into her childhood experiences as a grifter to help them navigate their escape, while Vivienne uses her poise and determination to keep them focused.

As their mutual respect deepens, old misconceptions unravel—especially around Teddy’s loyalties and the real source of their rivalry.

A wrong turn takes them to the French countryside, where a trio of young siblings offers shelter. There, Vivienne proposes a new route: rather than going to Paris, they should head to Rome and seek help from Sam Zimbalist, an American producer working on Ben-Hur.

During this pastoral pause, the women open up about their painful histories and find common ground. Vivienne learns Lottie’s romance with Teddy was never real, and Lottie sees Vivienne’s heartbreak not as bitterness but as emotional honesty.

They review the contents of the film canister and find damning photographs that confirm the existence of a drug smuggling operation using film props. Even more shocking is Gallo’s apparent role in the conspiracy.

In Rome, the chaos continues. Mistaken for extras on the Ben-Hur set at Cinecittà Studios, Vivienne and Lottie are nearly caught again.

A daring escape follows when Lottie steals a Ferrari and rescues Vivienne from Gallo’s men, ending in a wild chase and crash into ruins. The evidence is taken, and the women are separated aboard Gallo’s yacht.

Vivienne realizes how deeply she’s been manipulated—both by the industry and by Gallo himself. Her old belief in the redemptive power of cinema feels hollow, and her future appears grim.

Back on Tavalli, the stakes escalate. Gallo surrounds the set with armed men disguised as crew members.

With Max and Teddy’s help, Vivienne and Lottie hatch a final plan to escape and expose Gallo. The plan hinges on Vivienne distracting Gallo during a romantic dinner while the others swim to his yacht and radio for help.

The plan nearly works, but Ginger, another actress on set, is coerced into betraying them. Everyone is rounded up under the pretense of reshooting a scene, and they learn Gallo’s endgame: a massive explosion set off from the Trojan Horse prop, intended to kill everyone and destroy the evidence.

Vivienne, thinking quickly, leads the extras in a fake filming scene that turns into a real evacuation. Gallo tries to detonate the bomb with Vivienne in tow, but she jumps off a cliff with him.

She survives; he does not. Miraculously, Interpol arrives, having received the evidence Vivienne sent weeks earlier.

The crime ring is dismantled.

In the aftermath, Vivienne begins directing her first film. Lottie and Teddy regain their footing and embrace the possibility of change.

Even Ginger is given a cautious second chance. Vivienne and Lottie—no longer enemies—remain bonded by their shared ordeal, two women who proved themselves in a world that tried to use and erase them.

As Vivienne tentatively begins a new romance with an Interpol officer, she reflects on how much they both risked, and how much they’ve won back—especially their sense of self.

Characters

Vivienne Rhodes

Vivienne Rhodes stands at the dramatic heart of The Starlets, a woman whose evolution from spurned actress to heroic protagonist encapsulates much of the novel’s emotional and thematic weight. Initially introduced as a poised and disciplined star who has long fought for artistic legitimacy, Vivienne is blindsided when the iconic role of Helen of Troy—her anticipated vehicle to superstardom—is given to her rival, Lottie Lawrence.

This perceived professional and personal betrayal, especially with the painful reminder of her past relationship with Teddy Walters, fuels a simmering resentment. However, Vivienne does not retreat; instead, she digs into the complex role of Cassandra, pouring her ambition and frustration into transforming what was meant to be a footnote into a centerpiece of the film.

Her tenacity manifests not only in the battles she wages on set—demanding rewrites and creative control—but also in her survival instincts when confronted with the underworld conspiracy behind the movie production.

As the narrative evolves into a spy-thriller, Vivienne becomes a model of resourcefulness and steely resolve. She fends off danger with quick thinking, manipulates Jack Gallo with shrewd composure, and ultimately sacrifices her safety to protect others, culminating in a harrowing moment of bravery when she pulls Gallo over a cliff to stop a massacre.

Her character is also one of contradiction: deeply romantic yet emotionally scarred, ambitious yet increasingly disillusioned with the world of Hollywood illusions. By the end, Vivienne reclaims agency—not only surviving but thriving as she steps into a director’s role, a symbolic and literal reclaiming of narrative control.

Her journey is one of reinvention, resilience, and a sobering recognition of the cost of chasing dreams in a world that commodifies both art and women.

Lottie Lawrence

Lottie Lawrence begins as the sugary-voiced ingenue, a former teen idol trying to shed her saccharine image and be taken seriously in a cutthroat industry that resists transformation. Cast as Helen of Troy, she outwardly appears gracious and composed, but internally wrestles with fierce insecurities.

Her career has always been shadowed by the legacy of her manufactured persona, “Millie’s girl,” and her desperate attachment to Teddy Walters reveals a fear of instability masked by charm. Lottie’s complexity gradually unspools as the story progresses, especially when she finds herself unwittingly entangled in an international criminal operation.

Her discovery of the corpse and smuggling ring marks a turning point; she is no longer simply reacting to her circumstances, but acting to survive them.

Lottie’s evolution mirrors that of Vivienne, albeit in her own unpredictable way. She uses her con-artist instincts, honed from a grifter upbringing, to navigate the treacherous terrain from Tavalli to Rome.

Her talents—social engineering, disguise, quick improvisation—become invaluable assets, and the audience sees a woman shedding superficiality in favor of authenticity and grit. Lottie’s relationship with Vivienne, once rooted in rivalry and suspicion, transforms into one of solidarity and mutual respect.

Through shared trauma and peril, Lottie emerges not as the vapid starlet she feared being, but as a survivor capable of bravery and compassion. Her character arc is one of reclamation—of self-worth, of independence, and of a career no longer defined by public perception but by personal strength.

Jack Gallo

Jack Gallo enters The Starlets as the quintessential studio executive: charismatic, powerful, and seemingly invested in elevating art. He seduces Vivienne with promises of creative control and recognition, using flattery and influence to keep her tethered to the film.

At first, Gallo appears to be a savvy player in the Hollywood system—manipulative, yes, but perhaps no more so than others climbing the ladder. However, as the mystery unfurls, his charm peels away to reveal a chilling depth of corruption.

Gallo is not merely a cunning producer; he is a gangster hiding in plain sight, financing the film as a cover for drug trafficking and murder.

His character serves as both a foil and a predator. With Vivienne, he mimics the behaviors of a romantic lead, crafting a dinner on his yacht that echoes old-Hollywood glamour—only for the illusion to be violently shattered.

Gallo’s manipulation is psychological and physical; he uses the tropes of cinema—romance, power, spectacle—to control those around him. By the climax, Gallo stands as a symbol of unchecked power and exploitation, willing to sacrifice an entire cast and crew to protect his criminal enterprise.

His death, at Vivienne’s hands, is not just a narrative resolution but a cathartic act of rebellion against the systems he embodies.

Teddy Walters

Teddy Walters is both a symbol and a casualty of Hollywood’s performative intimacy. Once entangled romantically with Vivienne and later with Lottie, Teddy exists in a liminal space between love interest, collaborator, and pawn.

His initial betrayal—leaving Vivienne for Lottie—sets the emotional tension in motion, though it is later revealed that neither relationship was as genuine as the publicity suggested. Teddy’s affections have been shaped and repurposed by the studio machine, turning him into a hollow echo of romantic possibility rather than a truly autonomous figure.

Yet Teddy is not entirely passive. As the danger mounts, he steps into the fray, risking his life to support Vivienne and Lottie’s escape plan.

He plays a crucial role in the radio transmission to Interpol and becomes an ally in the unraveling of Gallo’s conspiracy. Still, his emotional depth remains somewhat elusive.

He is a man caught between the roles assigned to him—lover, actor, hero—and the reality of his limited control. In the end, Teddy becomes a figure of redemption more than revolution; someone who, though complicit in Hollywood’s artifice, tries to make amends and stand for something real.

Max Montrose

Max Montrose is the moral conscience buried beneath layers of secrecy. A blacklisted screenwriter operating in the shadows, Max is defined by his idealism and his bitterness.

His career has been fractured by McCarthyism, and he writes not for glory but out of a stubborn need to speak truth—even when doing so means hiding behind others’ names. His romantic involvement with Teddy adds emotional nuance to his character, further complicating the web of personal connections that bind the film’s ensemble.

Max’s intelligence and cautious temperament make him essential to the heroines’ plan. He is the one who recognizes the full implications of the smuggling ring, and despite his cynicism, he joins Lottie and Vivienne in their quest for justice.

His emotional bond with both men and women in the narrative speaks to his layered identity, one that defies the era’s rigid expectations. While never the spotlight character, Max provides the infrastructure of resistance: strategy, information, and quiet resilience.

He is proof that integrity, though often punished, can endure and matter.

Ginger

Ginger is a side character who nonetheless plays a crucial role in the climax of The Starlets. As an extra on the film set, she is initially unassuming, part of the sprawling background of Hollywood’s supporting machinery.

However, her actions take on tragic weight when she inadvertently betrays Vivienne and the others by revealing their plan under duress. Her betrayal is not born from malice, but from fear, placing her in the gray zone of human weakness.

She embodies the cost of terror, the unintended consequences of coercion.

In the aftermath, Ginger is given a second chance, though the trust she once held is fractured. Her character reflects the fragility of loyalty under pressure and the moral complexity of survival.

She is not demonized, but she is not redeemed easily either. Ginger serves as a narrative reminder that in a world of performance and peril, even minor players hold the power to alter destinies.

Her arc, though brief, underscores the pervasive anxiety and ethical ambiguity that shape the novel’s world.

Themes

Power, Performance, and the Female Gaze

The Starlets consistently explores how women navigate male-dominated systems that treat them as disposable objects and demands their compliance for survival. Vivienne and Lottie exist within the rigid machinery of 1950s Hollywood, where their worth is often measured not by talent but by appearance, obedience, and utility to men in power.

This manifests in the film production of A Thousand Ships, where roles are doled out not purely on merit but through backdoor negotiations, studio alliances, and private affairs. Vivienne, though a seasoned actress, is blindsided when the role of Helen is handed to Lottie—a betrayal loaded with personal and political implications.

Her relegation to Cassandra might seem like a loss, but Vivienne’s transformation of the character from ornamental to central figure becomes an act of rebellion. She asserts her creative voice not in spite of the system, but in direct challenge to it, using performance to reclaim agency.

Lottie, meanwhile, attempts to pivot away from her pop persona to be viewed as serious and dimensional. Her desire to escape the infantilizing “Millie’s girl” image illustrates how women are boxed into narrow archetypes in media narratives.

The tension between Helen and Cassandra becomes more than just a plotline; it reflects the societal compartmentalization of women as either adored or discarded, desired or deranged. These actresses’ fight for respect both onscreen and off is a larger battle over who controls the gaze—men like Gallo or women like Vivienne who refuse to be sidelined.

Their performances turn into political acts, weaponized against systems designed to erase them.

Betrayal, Loyalty, and Trust in a World of Illusions

Trust is dangerously scarce in the world of The Starlets, where deception is woven into every layer of personal and professional interaction. Romantic relationships are often masks for manipulation, as illustrated in Vivienne’s romance with Teddy, which started as a studio-mandated publicity stunt but evolved into something more emotionally entangled—and then ended in heartbreak.

Lottie’s attachment to Teddy, too, is less about affection than about strategic survival. Her fear of professional irrelevance and emotional abandonment compels her to hold onto Teddy, even though his own loyalties lie elsewhere.

The revelations about Teddy’s relationship with Max Montrose compound this sense of betrayal, as do the shifting allegiances between the trio. Even supposed allies—like Gallo or Ginger—prove themselves capable of manipulation, betrayal, or collapse under pressure.

Ginger’s eventual decision to expose Vivienne’s plan is framed as coerced, but it nonetheless confirms that loyalty in this world is conditional and brittle. Against this backdrop of betrayal, the gradual alliance between Vivienne and Lottie becomes all the more remarkable.

Their initial interactions are filled with venom and one-upmanship, yet shared danger forces them into a fragile alliance. That bond evolves into mutual respect, forged not through sentimentality but through necessity, sacrifice, and earned understanding.

It is through this crucible of betrayal that genuine loyalty emerges—not romantic, not platonic, but something more rare: the loyalty of two survivors who have learned they can rely only on each other in a world where everyone else wears a mask.

Survival, Grit, and Feminine Ingenuity

The progression of Vivienne and Lottie from rivals to reluctant fugitives and ultimately resourceful heroines underscores a deeper theme of feminine survivalism. When thrust into life-threatening situations, these women display not just courage, but a sharp tactical mind that undercuts the stereotype of the fragile starlet.

Whether escaping armed smugglers or executing a fake movie scene to incite mass evacuation, their intelligence, creativity, and audacity are the very traits that save them time and again. Lottie draws heavily on her upbringing among grifters—an origin story often coded as shameful—to manipulate situations, fabricate personas, and execute clever cons.

Vivienne, on the other hand, combines her classical poise and intuition to navigate dangerous social environments and manipulate powerful men like Gallo without succumbing to them. These abilities are not framed as exceptions but as essential traits of womanhood in a treacherous world.

What’s powerful about their resourcefulness is that it’s grounded in their knowledge of performance, perception, and emotional fluency—tools typically dismissed as “feminine” but which, in this context, become lethal survival strategies. The actresses use their public roles—Cassandra and Helen—not just as characters, but as avatars in a real-life game of espionage and resistance.

Their success, ultimately, is not due to brute strength or male intervention but to their own strategic brilliance. The Starlets positions survival as a distinctly feminine art, one honed through years of adaptation, emotional labor, and underestimation.

Corruption and the Underbelly of Glamour

Behind the cinematic spectacle of A Thousand Ships lies a brutal reality of exploitation, criminality, and moral rot. The glimmering production set masks a smuggling operation, and its executive producer, Jack Gallo, is not just a studio boss but a gangster orchestrating a multinational drug enterprise.

The Trojan horse becomes a literal embodiment of hidden threat—what looks like art is in fact a vehicle of death. This juxtaposition of movie magic and grim corruption lays bare the illusion of glamour, suggesting that the film industry, like the horse, is hollowed out by greed, violence, and ambition.

The narrative makes clear that even supposedly benevolent figures like Zimbalist are powerless to stop the rot when the rot wears a charming smile and bankrolls entire productions. The stardom and pageantry that drew Lottie and Vivienne to Hollywood are revealed as perilous facades, upheld by men who trade bodies, secrets, and power under the cover of scripts and cameras.

The ultimate climax—involving dynamite-packed props, a fake shoot turned real escape, and a literal fall off a cliff—symbolizes how fragile the veneer of control is in a system built on lies. Gallo’s death is not just the fall of a villain, but the collapse of an industry that enabled him.

Yet even amidst the corruption, the survival and resilience of Vivienne and Lottie suggest that justice, while not always institutionally enforced, can emerge through individual action and moral clarity.

Reinvention and the Search for Authentic Identity

For both Lottie and Vivienne, the journey across the Mediterranean and into the heart of a criminal conspiracy is ultimately a journey toward self-definition. These women are burdened by constructed identities imposed by the studio system.

Lottie is the forever ingénue, sweet and palatable, her image tightly controlled by branding and fan magazines. Vivienne is the tragic beauty, doomed to be sidelined for younger, more “marketable” women.

Their quest to reclaim control over their lives—whether through creative reinvention of a role or through real-life heroism—mirrors the struggle to be seen as full, complex human beings rather than archetypes. This reinvention comes at personal cost.

Vivienne must let go of illusions about Teddy, romance, and the safety of the Hollywood dream. Lottie must confront the emptiness of her carefully curated persona and the reality that her fame alone cannot protect her.

Their ability to shed false skins, to embrace vulnerability, to rewrite their own scripts in the midst of chaos, speaks to the deeper theme of identity reclaimed. In directing her own film at the end, Vivienne doesn’t just become a filmmaker—she asserts her authorship over her narrative.

Lottie, too, finds purpose beyond her image, supported not by PR agents or tabloids but by people who know her fully. The Starlets closes not with triumph in the traditional sense, but with something far more earned: a quiet, hard-won sense of self, forged in fire and freed from illusion.