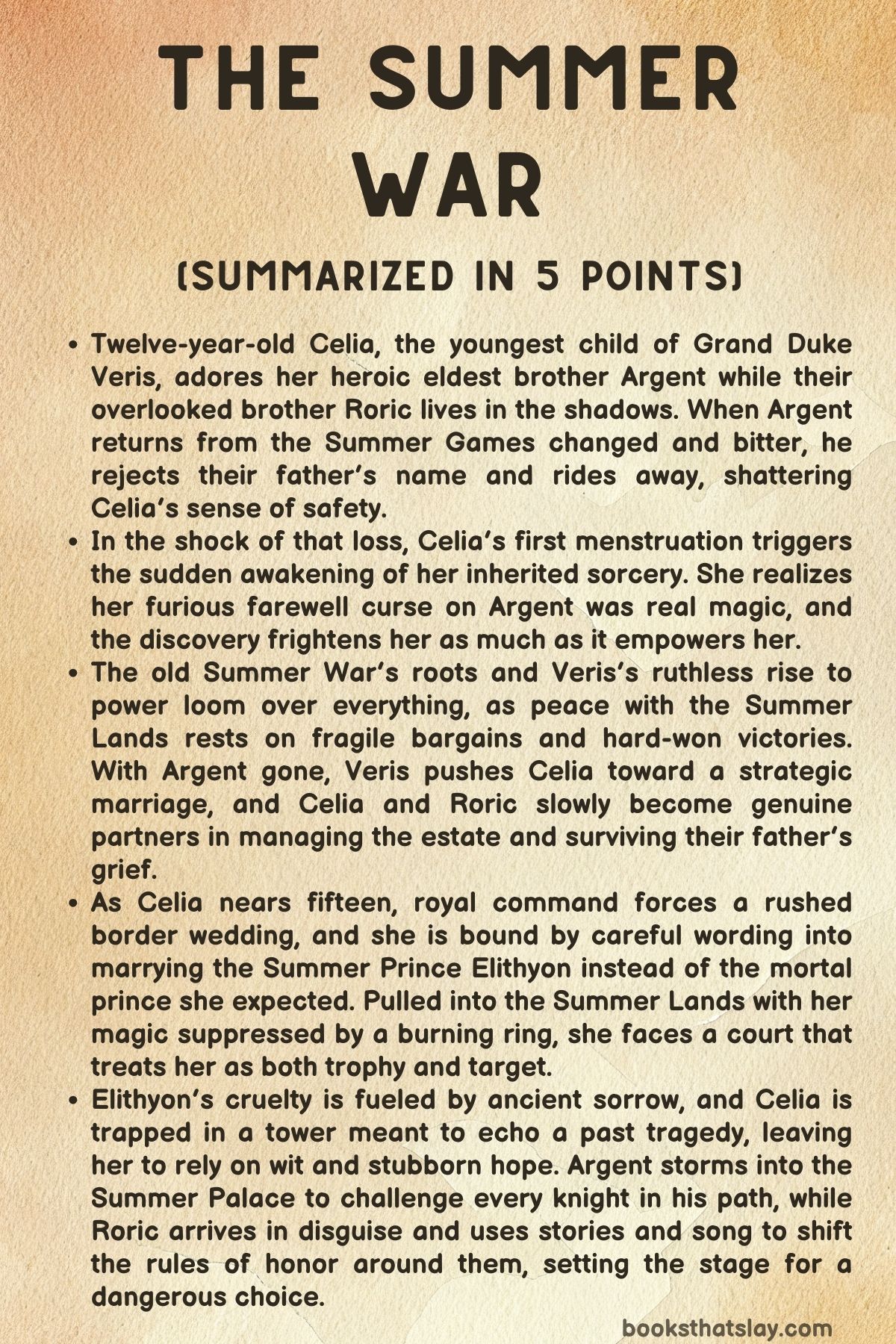

The Summer War Summary, Characters and Themes

The Summer War by Naomi Novik is a fantasy novel set on the uneasy border between mortal Prosper and the magical Summer Lands. It follows Celia, the youngest child of Grand Duke Veris, whose sheltered life collapses when her beloved brother Argent renounces their father and vanishes across the border.

Celia’s grief awakens a powerful, dangerous sorcery inside her, tying her fate to the long history of a war sparked by betrayal and pride. As politics tighten around her and old wounds reopen, Celia must reckon with the cost of love, vengeance, and the bargains that bind two worlds.

Summary

Celia of Prosper is twelve years old, the youngest child of Grand Duke Veris. She adores her eldest brother, Argent, heir to their father’s seat, and views him as a hero without flaw.

He has always included her in his world—teaching her to ride, dance, and carry herself like a noble—while promising that he will keep her safe. Their other brother, Roric, has never been granted the same place.

Born to a common woman who died, he is treated as a shadow in the household, barely acknowledged by Veris or the court.

One year Argent rides to the famed summer games on the border, a tournament where mortal knights test themselves against summerlings. He returns crowned in glory, having defeated many opponents, and a song-spinner brings news that the Summer Prince, Elithyon, honored him with a rare sword braided of silver, gold, and steel.

Yet when Argent comes home in late autumn, he is changed. He is colder, harder to reach, and avoids Celia’s eager questions.

She follows him to the library and overhears a heated meeting with their father. Argent refuses the welcome cup and says he will not stay.

He tells Veris a story from childhood: during a visit to court, Veris punished two men who loved each other, stripping them of their names and casting them out after a public beating. Argent explains that even as a boy he knew he desired men and lived terrified that Veris would do the same to him.

After days of waiting for his father to notice and condemn him, he tried to end his own life with nightshade. He survived.

Veris soothed him and told him to rest, but Argent now understands that comfort as a lesson: not acceptance, but training in secrecy and obedience. Argent returns the family sword, declares he will no longer carry Veris’s name, and leaves for the Summer Lands, intending never to return.

Celia runs to the stables barefoot and begs him to stay. Argent answers with a flat, distant calm that he cannot live in his father’s house.

Celia, shattered by what feels like indifference from the person she loved most, lashes out. She accuses him of abandoning her while she is destined for a political marriage, while he seeks adventure and lovers across the border.

Argent cannot deny it. In rage and sorrow, Celia screams that he should go and speaks a curse: that he will meet a hundred beautiful summerling boys and never be loved by any of them.

Argent rides away without looking back.

Left alone in the stable corridor, Celia discovers her first menstruation. The shock of blood and grief unlocks a buried inheritance: sorcery from the royal bloodline.

Terror follows immediately. When guards rush to her screams, their swords turn to glass and shatter in their hands.

Celia realizes her curse was not childish talk. It was magic.

The story widens to the past. The century-long summer war began when Elithyon’s sister, Princess Eislaing, was married to King Sherdan of Prosper to form peace.

On her wedding night she believed Sherdan loved a mortal song-spinner. Humiliated and despairing, Eislaing killed herself.

Elithyon swore vengeance, and for a hundred summers the Summer Lands invaded Prosper, retreating each autumn when their power faded. Prosper endured through border forts and ritual duels until Veris, once a poor northern knight, rose by ruthless skill.

He used ambushes, feints, and merciless strategy to win victory after victory, ending the war and earning a dukedom and royal marriage. With peace secured, he aimed next at the throne, arranging future matches for Argent and Celia to tighten his family’s grip on power.

Argent’s flight wrecks those plans. Veris attempts to betroth Celia to a widowed duke, but she refuses.

Newly aware of her magic, Celia insists she is worthy of marrying Crown Prince Gorthan instead. Veris agrees, writes to the king, and then collapses into grief, withdrawing from rule.

Celia turns to Roric. She tells him Argent is gone and that he is now heir.

Roric admits that almost no one has cared for him except Celia’s late mother, and asks Celia to care for him too. She agrees, and the two begin managing the estates together in her mother’s old sitting room.

Their bond grows through shared work, books, and music, while Veris drifts in sorrow.

Every summer, travelers bring true tales of Argent, now known as the Knight of the Woven Blade. He completes perilous quests in the Summer Lands, defeating monsters and champions alike, yet never stays with anyone.

Celia becomes convinced that her curse has stripped him of the love he sought and driven him toward ever higher feats that cannot fill the emptiness beneath. With Roric’s help, she plans to cross the border, find Argent, and undo the curse before her marriage seals her away from choice.

But in the spring after Celia turns fifteen, King Morthimer commands that she come at once to the Green Bridge for an immediate wedding to Gorthan. Veris and Celia travel to the border and see that the Green Bridge town and palace are shabby ruins, not the bright half-summer sanctuary of legend.

Veris doubts the peace and warns Celia to conserve her magic. Then the living Green Bridge rises from the mist and the wedding preparations begin under heavy summerling watch.

Gorthan arrives with an honor guard and escorts Celia into the wedding grove. The priest makes her swear she comes freely to marry “the prince.

” As they walk through layered curtains of flowering vines, Celia feels strange flashes of memory and disorientation, as if her mind is being nudged off course. In a hidden clearing, the truth is revealed: the “prince” she swore to is not Gorthan, but Elithyon.

The old peace terms require the next sorceress of Sherdan’s bloodline to marry the Summer Prince, repaying the bargain that once sent Eislaing to Prosper. Celia protests, but the wording binds her.

Elithyon places a coal-dark ring on her finger. It burns and smothers her magic.

Gorthan, ashamed yet firm, refuses to stop the ritual, claiming prophecy says Prosper’s sorcery will be stolen. Celia is taken across the threshold into the Summer Lands.

Elithyon leads her through a hostile forest, enjoying her fear. When Celia’s anger steadies, the path shortens and smooths under her will, hinting that her power is not fully gone.

At the Summer Palace a feast begins. Celia fears enchanted food and secretly keeps mortal bread from home.

The summerlings drink potent liquor, dance, and pair off openly. Elithyon kisses another man in full view and ignores Celia.

She is relieved by the distance and tries in vain to pry off the ring. Later he returns to declare he will never love or honor her.

She will be queen only in name, a living revenge for Eislaing’s death. He drags her to a pale stone tower and locks her inside.

In the morning Elithyon finds her alive and is furious; he expected her to die as Eislaing did by leaping from the tower. He recounts Eislaing’s humiliation and vows Celia will never leave the chamber except the same way.

Celia discovers the tower’s magic prevents her from harming herself or even cutting off her ringed finger. She is trapped in a cruelty meant to echo an old tragedy.

That day a vast court gathers below. A legendary shaihul arrives carrying Sir Argent.

He has become a living myth in the Summer Lands, and he demands Celia’s release. Elithyon refuses but is bound by summer honor to allow combat.

Argent throws down his gauntlet and challenges any summer knight who bars him to face him one after another. The courtyard erupts.

From her window Celia hears and sometimes sees Argent fight with deadly grace. He cuts down knight after knight.

Elithyon repeatedly halts the duels for rest, torn between rage, honor, and growing horror at the mounting dead.

Celia considers ending her life to stop the slaughter, but she knows her death would reignite war across both realms. The duels continue until seventy-eight summer knights lie dead.

At last Elithyon tries to bargain: Argent should withdraw and Celia will live comfortably in captivity. Argent refuses each time.

As his strength begins to fail, a new performer arrives—Roric, disguised as a song-spinner. Elithyon invites him to sing.

Roric tells absurd account-stories that charm the court and delay the next duel. Finally he sings a sharp new version of a familiar tune, naming it “The Summer War.

” The song condemns Elithyon’s vengeance against innocents while the true heirs of betrayal still rule Prosper. The words jolt Elithyon into clarity.

He admits he has taken the wrong revenge.

Roric reveals his final move: before singing, he lured Elithyon into swearing not to harm him or any of his kin. Since Celia and Argent are Roric’s siblings, Elithyon cannot allow Argent to be killed.

To satisfy both the public challenge and the oath, Elithyon takes up arms himself and declares he will be the last challenger. If Argent defeats him, no one else may stand in his way and Celia will go free.

Elithyon offers Argent an open guard, inviting a fatal strike. Argent cannot bring himself to kill a prince who has just shown remorse, and Celia understands the trap of her old curse: Argent is forced to choose Celia above all others, even at the cost of his own soul.

Seeing the impasse, Celia calls the shaihul Alimathisa to her window and asks it to help her “jump. ” The creature rises, and Celia steps onto its back and descends safely from the tower, technically leaving the way Eislaing did.

The tower’s binding breaks. In the courtyard, Veris appears in disguise and demands Elithyon remove the ring and release Celia.

He argues she is not a pawn but Prosper’s future ruler, then offers Argent as Elithyon’s companion to seal peace instead. Elithyon accepts, and the ring is taken off, restoring Celia’s full power.

Back in Prosper, Veris exposes the king and Gorthan’s treachery. With public outrage and weapons forged with summer magic, he forces them to abdicate and flee north.

Celia claims the throne. She restores the ruined Green Bridge palace with her sorcery and with summerling aid, planting new living halls where bitterness once stood.

A coronation and renewed peace-wedding follow, celebrated by mortals and summerlings together. Celia formally gives Argent to Elithyon as part of the treaty.

They kiss, the grove bursts into bloom, and the long war between Prosper and the Summer Lands ends in a peace built on truth rather than coercion.

Characters

Celia

Celia begins The Summer War as a twelve-year-old who has only ever known her family’s courtly world and the gentle certainty of her brother Argent’s protection. Her idolization of Argent is not childish fluff but the emotional center of her early identity: he represents safety, admiration, and the promise that love in her life will be uncomplicated.

When he abandons the household, Celia’s heartbreak detonates into rage, and that emotional extremity is the doorway through which her sorcery arrives. The awakening of her magic at menarche links power to bodily change and to grief, making her abilities feel less like a gift and more like an extension of her volatile inner life.

As she grows, Celia’s arc becomes a study in responsibility forged through guilt. She believes her curse has hollowed Argent’s life, so her desire to undo it is both love and penance.

In the Summer Lands, she’s yanked out of political innocence and forced to read language precisely, because her oath is weaponized against her. The ring that suppresses her magic also suppresses her sense of agency, and her survival in the tower requires learning a different kind of power: persuasion, endurance, and strategic empathy.

By the end, Celia has moved from reactive emotion to deliberate rule. She chooses to live even when death could end the duels, because she understands that her personal despair is tied to realm-wide consequences.

Her final claim to the throne shows a ruler who fuses mortal pragmatism with summer sorcery, rebuilding not just a palace but the symbolic relationship between worlds.

Argent

Argent is introduced as the flawless heir and storybook knight, but The Summer War steadily reveals how much of that brightness is armor. His childhood memory of Veris’s brutal punishment of two men for loving each other becomes the secret wound that shapes his life.

Argent’s queerness is not treated as a simple trait; it is tied to terror, self-loathing, and the suffocating logic of a household that equates desire with danger. His attempted poisoning with nightshade shows how close he came to being erased by his own fear, and his later interpretation of his father’s “comfort” as a lesson in concealment turns love into a kind of trap.

When he leaves, he isn’t only fleeing Veris; he is fleeing a future in which he’d have to keep cutting pieces off himself to fit the role of Prosper’s heir. Celia’s curse then twists that flight into a different prison: he becomes the Knight of the Woven Blade, endlessly heroic yet emotionally unreachable, acquiring glory without intimacy.

His arrival at the Summer Palace is Argent at his most tragic and most noble—willing to kill a small army to reach Celia, but also trapped by the curse into choosing her over any other attachment. The climactic moment where he cannot kill Elithyon shows the rupture between who he has been forced to be and who he wants to become; he’s horrified not by mercy, but by the realization that even compassion is being controlled by magic he never consented to.

Argent ends the story still a knight, but now one who can finally choose love without the shadow of his father’s rules or his sister’s unintended spell.

Roric

Roric starts as a ghost in his own home, a son of a dead common-born wife who is tolerated rather than loved. The household’s neglect could have made him bitter or reckless, but Roric’s defining trait is a quiet resilience that grows into cunning.

Celia’s decision to tell him he is now heir becomes the first real recognition he has ever received, and his response—asking her to care for him too—shows both his vulnerability and his hunger for belonging. Their partnership in managing the estates reveals Roric as practical, intelligent, and patient, someone who can turn marginalization into careful observation.

In the Summer Palace, his disguise as a song-spinner is a turning point: he weaponizes the role Prosper typically sees as ornamental, using story and humor as battlefield tools. His “account-stories” are more than comic relief; they are a deliberate reshaping of the court’s attention, slowing violence and creating a space where truth can land.

The song “The Summer War” is his sharpest blade, forcing Elithyon to see the cruelty of misplaced vengeance. Roric’s genius is legal and narrative: he traps Elithyon in a self-made oath that protects his siblings, proving that intellect and artistry can do what armies can’t.

By the end, Roric has stepped out of invisibility into influence, not by demanding status, but by demonstrating that Prosper’s future needs minds like his as much as it needs magic or swords.

Grand Duke Veris

Veris is one of the book’s most morally tangled figures. In Prosper’s history, he is the ruthless savior who ended a century of summer invasions through deception and tactical brilliance.

That record makes him a nationalist hero, but it also reveals a man who believes survival justifies harshness. As a father, Veris is simultaneously protective and terrifying.

His punishment of the lovers at court wasn’t only cruelty; it was political theater, an enforcement of norms meant to stabilize rule, and he expects his children to absorb that lesson. Argent’s confession forces Veris into a complicated response: he does not destroy his son, but neither does he affirm him.

Argent interprets his father’s tenderness as a warning to hide, and that ambiguity suggests Veris loves within the limits of what his world allows him to imagine. After Argent leaves, Veris’s grief is real enough to unmoor him, yet even that sorrow is braided with ambition—his plan for perfect marital alliances collapses, and he reacts by clinging harder to control.

In the Summer Lands, however, Veris reemerges as the strategist who ended the war. His disguised entry, his demand that Celia be treated as a sovereign future queen, and his bold offer of Argent as Elithyon’s companion show a man who sees peace as a structure that must be actively built, not passively inherited.

Veris is not redeemed into softness; instead, he is revealed as someone whose love is fierce, flawed, and expressed through power plays because that is the language he knows.

Elithyon

Elithyon embodies the Summer Lands’ beauty sharpened into cruelty. He arrives as a prince whose identity is inseparable from an old wound: Eislaing’s suicide at her wedding and the humiliation she endured in Prosper.

His vengeance has calcified into ritual, and Celia’s forced marriage to him is meant as repayment with interest. At first, Elithyon wants Celia frightened, powerless, and dead, replaying history until it feels balanced.

His use of the coal-dark ring to suppress her sorcery shows his fear of mortal power as well as his desire to dominate the narrative. Yet Elithyon is also bound by summer honor, which makes him capable of being trapped by language and oath.

The mass duels against Argent crack his certainty: each death is both satisfaction and a growing horror, because summer honor turns vengeance into self-destruction. Roric’s song jolts him into recognizing that he has punished the wrong heirs for the wrong sins, and this moment doesn’t erase his grief but redirects it.

His choice to become the final challenger and offer himself to Argent is the first true act of care he’s shown since Eislaing’s death. By accepting Argent as companion and agreeing to peace, Elithyon becomes a prince who finally values restoration over repetition.

He doesn’t stop being proud or dangerous; he simply learns that love and honor are not opposites, and that grief can be honored without being endlessly reenacted.

Crown Prince Gorthan

Gorthan is a character shaped by dynastic pressure and fear. Celia expects him to be her husband, and he performs that role long enough to shepherd her into the grove, but his complicity in the trick marriage marks him as someone who prioritizes duty over personal honor.

His shame during the ceremony is genuine, yet he refuses to intervene, clinging to prophecy and political justification. In accusing Veris of treachery and claiming sorcery will be stolen, Gorthan reveals his worldview: magic and bloodlines are resources to be controlled, and he believes betrayal is acceptable if it protects the crown.

He is not motivated by sadism like Elithyon initially is; his cruelty is bureaucratic, the cold violence of someone who thinks the realm’s stability requires sacrificing a girl’s choice. When Veris exposes the plot and forces abdication, Gorthan’s collapse shows that his authority was never rooted in moral legitimacy, only in inherited power.

King Morthimer

King Morthimer represents the rot at the top of Prosper’s monarchy. His command to rush Celia to an immediate wedding, regardless of her consent or Veris’s position, exposes a ruler who treats people as bargaining chips.

His participation in the peace terms demonstrates either cowardice before the Summer Lands or opportunism at Veris’s expense, but in either case he is willing to trade a young sorceress into captivity to preserve his own throne. The public outrage after his treachery suggests his rule depended on secrecy and tradition rather than any shared trust.

His flight north is not merely defeat; it is the story’s indictment of kings who survive by outsourcing their violence to others.

Princess Eislaing

Eislaing is absent in body but central in consequence. Her suicide at her wedding is the spark that ignites the century-long summer war and the emotional engine behind Elithyon’s rage.

She appears as a symbol of a woman crushed between political bargains and personal humiliation, and her death becomes a story both realms tell to justify their actions. What makes Eislaing compelling is that she is not used as a simple martyr; her fate illustrates how patriarchal power in Prosper and honor-bound vengeance in Summer can collaborate in destroying a person.

Celia’s tower imprisonment is designed to force her into Eislaing’s shape, and the fact that Celia escapes by technically leaving the same way reframes Eislaing’s story from inevitable tragedy into a warning about what happens when grief is left to fester into policy.

King Sherdan

Sherdan’s role in the background is that of the original oppressor. His alleged love for a mortal song-spinner and the humiliation of Eislaing after their wedding are described as the foundational sin Prosper never properly atoned for.

Whether he was truly unfaithful matters less than the way his court used rumor and cruelty to isolate Eislaing until death felt like her only autonomy. Sherdan stands for a kind of royal entitlement that treats summerlings as exotic trophies and mortals as disposable entertainment.

The war and all later bargains are haunted by the careless violence of his rule.

Alimathisa and the shaihul

Alimathisa, the legendary shaihul, functions as more than a magical creature; it is the hinge between literal and legal escape. Its arrival bearing Argent underscores the Summer Lands’ mythic scale, but its deeper narrative importance lies in Celia’s clever use of story-logic.

By asking Alimathisa to come so she can “jump” onto its back, Celia meets the letter of Elithyon’s grim rule while rejecting its spirit. The shaihul therefore represents a different kind of summer power—ancient, impartial, and responsive to boldness rather than hierarchy.

In a book obsessed with oaths, wording, and bargains, Alimathisa is the living proof that imagination can be a form of lawbreaking without breaking the law.

The song-spinners

Though not individualized, the song-spinners are a subtle force threading through The Summer War. They carry news across borders, turning private acts into public legend and shaping how both realms understand heroism and blame.

A song-spinner’s report of Argent’s gifted sword launches his myth, and Roric’s own use of the song-spinner role shows how storytelling can be an instrument of resistance. In a political landscape where oaths bind bodies, songs bind memory, and the spinners are the keepers of that softer, dangerous power.

Themes

Forbidden love, identity, and the cost of repression

Argent’s break from his father sets the emotional temperature of The Summer War and exposes how desire becomes political when a ruling house treats love as property. Veris’s childhood punishment of two men for loving each other is not presented as a private cruelty but as a public performance meant to shape the entire duchy’s sense of what is allowed.

Argent grows up internalizing that lesson: love is not simply risky; it is something that can erase your name, your place, and your future. His attempted suicide as a boy shows how repression turns inward, producing self-destruction long before any external enemy can strike.

When he returns from the summer games hardened and ready to abandon his title, that decision is less a teenage rebellion and more a survival choice. He refuses the welcome cup, rejects the family sword, and discards Veris’s name because each of those objects symbolizes a system that requires him to lie to live.

The theme is complicated by Veris’s later tenderness toward Argent; the father is not a cardboard tyrant but a man who believes he is protecting his heir by teaching him to hide. That belief makes the harm deeper, because affection becomes another instrument of control.

Celia’s curse, flung in grief, then traps Argent in a different kind of coercion: he is chased by beauty and glory but denied the love he seeks, mirroring the earlier denial imposed by his father. By the end, Argent’s bond with Elithyon offers a form of recognition that Prosper could never give him.

Yet it is not framed as a neat reward after suffering. Instead it highlights how queer love must fight for space in worlds built on dynastic plans and moral policing.

The story insists that denying someone the right to love freely is not a side issue; it is a primary engine of exile, war, and broken families.

Coming of age, sorcery, and the struggle for agency

Celia’s first menstruation and sudden awakening of power tie bodily change to political awakening in a way that refuses to sentimentalize either. Her magic arrives violently, without warning or instruction, and with it comes the knowledge that words spoken in anger can rewrite reality.

That terror is crucial: power is not initially liberating for her, it is frightening because it shows she can hurt people without meaning to. As Veris immediately pivots from mourning Argent to bargaining Celia’s marriage, Celia begins to understand how girls in Prosper are positioned.

Their value is paired to alliances, their futures arranged as pieces on a board. Her insistence that she should marry Gorthan because she is a sorceress is not simple ambition; it is her first attempt to convert innate power into choice.

Even that choice is thwarted through legal wordplay at the Green Bridge, showing how agency can be stolen not only by force but by language. In the Summer Lands she is a queen in name only, her ring burning away her magic and her autonomy together.

Elithyon’s demand that she reenact Eislaing’s suicide tries to reduce her to a symbol in his revenge story. Celia’s refusal to die is an early act of self-definition: she chooses messiness and survival over mythic purity.

Her later decision to call the shaihul and step out of the tower on its back is both clever and daring, a moment where she reclaims power without breaking the rules that bind her. She does not wait to be rescued; she engineers the condition for her own freedom.

By the conclusion, when she seizes the throne and rebuilds the Green Bridge palace through sorcery, her growth is complete but not portrayed as effortless triumph. She learns to treat magic as responsibility rather than impulse, to rule as a person rather than a pawn, and to hold grief and love without letting either decide her fate.

Her coming of age is therefore not about innocence lost but about authorship gained: she becomes someone who can name her own life in a system designed to name it for her.

Vengeance, mercy, and the echo of old wars

The century-long conflict between Prosper and the Summer Lands begins in personal pain, but The Summer War keeps asking what happens when grief is turned into policy. Eislaing’s suicide is a tragedy that Elithyon cannot release; he converts his sister’s humiliation into a doctrine of seasonal invasion.

The insistence on repeating violence every summer suggests that revenge can become a calendar, a ritual that outlives the original wound. Veris ends the war through ruthless tactics, which seems at first like pragmatic heroism, yet his methods also show that peace born only from domination is fragile and morally compromised.

Both sides claim righteousness while using people as sacrifices. Elithyon’s treatment of Celia repeats the structure that broke Eislaing: a bride becomes the stage where one realm demonstrates power over another.

His hope that Celia will kill herself is not only cruelty but also an attempt to validate his worldview, to prove that Prosper’s heirs deserve endless punishment. The duels in the courtyard reveal revenge’s spiraling cost.

Argent’s challenge is framed in honor terms, yet each fallen summer knight is another body added to a ledger that no longer clarifies justice. Elithyon’s visible distress as the deaths rise emphasizes that vengeance traps the avenger too; he is bound to a narrative he no longer fully believes, but pride and grief keep him inside it.

Roric’s song “The Summer War” functions like a moral intervention. By mocking Elithyon’s selective targeting and naming the innocents already harmed, Roric forces a reckoning: the wrong he suffered cannot justify wrongs against strangers.

When Elithyon chooses to fight as the final challenger and offers his own life to end the slaughter, the theme turns toward mercy not as softness but as courage. It takes more strength for him to admit his mistake than to keep killing.

The final peace is therefore not a simple handshake between nations; it is a shift from inherited vengeance to chosen responsibility. The story suggests that wars sustained by memory alone will never end until someone refuses to keep paying the same emotional debt with new blood.

Oaths, language, and the power of constraints

Few forces in The Summer War are as binding as the words characters speak. Celia’s wedding oath is shaped to sound harmless, yet its vagueness is a weapon aimed at her future.

The priest’s phrase “the prince” becomes a trapdoor that drops her into the Summer Lands, revealing how legal and ceremonial language can function as violence when wielded by those who control its interpretation. The magic system aligns with this idea: Celia’s curse on Argent is effective because spoken intent matters, even when she is a child who does not yet grasp consequence.

Her words create a fate that neither of them can later shrug off. Summer honor similarly operates through verbal contracts that cannot be broken without unraveling identity.

Elithyon, who begins as the architect of a cruel bargain, is later halted by a promise he gives Roric. The cleverness of Roric’s strategy highlights a theme of fighting power with language rather than steel.

By extracting an oath not to harm him or his kin, Roric makes Elithyon’s own code into a cage that protects the siblings. The dueling ritual works the same way.

Argent uses the summer court’s rules to demand passage to Celia, forcing the court to face the real price of their traditions. These constraints are not shown as purely negative.

They can be tools for survival and bridges to trust when entered freely and honestly. Celia’s escape from the tower depends on exact wording: she leaves the chamber “the same way” Eislaing did, but interprets that phrase with creativity rather than despair.

The world is one where outcomes hinge on how you read, hear, and honor words. That makes every vow a test of character.

Gorthan’s shame at the deception underscores that even when oaths are manipulated successfully, they corrode the one who benefits. In contrast, the renewed peace-wedding at the end matters because it is not based on trickery; it is a spoken agreement aligned with real intent.

The book argues that language is never neutral: it can imprison, protect, distort truth, or restore it, depending on who speaks and who is allowed to define meaning.

Family, loyalty, and the choice to care

The central relationships of The Summer War explore family as both wound and refuge. Celia’s devotion to Argent begins in childhood hero worship, yet it matures into something harsher when he leaves.

Her grief is not only about losing a brother; it is about losing the person who made her feel seen in a household governed by Veris’s cold expectations. Argent’s departure fractures the family structure and exposes how love can be conditional inside dynastic systems.

Veris loves his children, but he loves control more, and that priority turns his home into a place where some members are celebrated and others erased. Roric embodies that erasure.

Treated as a nonentity because of his mother’s status, he grows up expecting nothing from anyone. Celia’s decision to name him heir and run the estates with him is therefore radical in its quietness.

It is care offered without strategy, and it allows Roric to become fully himself. Their partnership in the sitting room—shared books, music, and work—shows chosen loyalty repairing damage that blood ties alone could not heal.

When Roric crosses into the Summer Lands disguised as a song-spinner, it is not for glory but for family. His courage is built from the belief that someone finally needs him.

Argent’s loyalty, too, is complicated. He returns for Celia even though Prosper rejected him, and he is willing to die in a duel chain that seems hopeless.

His love for her exists alongside his quest for a life where he can love freely, so his sacrifice is not simple self-denial but a painful balancing of truths. Celia eventually recognizes that her possessive curse has forced Argent into a role he never chose, and freeing him is part of her growth.

The final arrangement—Argent joining Elithyon, Celia ruling Prosper, Roric honored as kin—redefines family as a web of responsibilities that can change shape without breaking. Loyalty in this story is not obedience to a patriarch or to tradition; it is the repeated choice to protect each other’s futures, even when that means letting go.