The Temple of Fortuna Summary, Characters and Themes

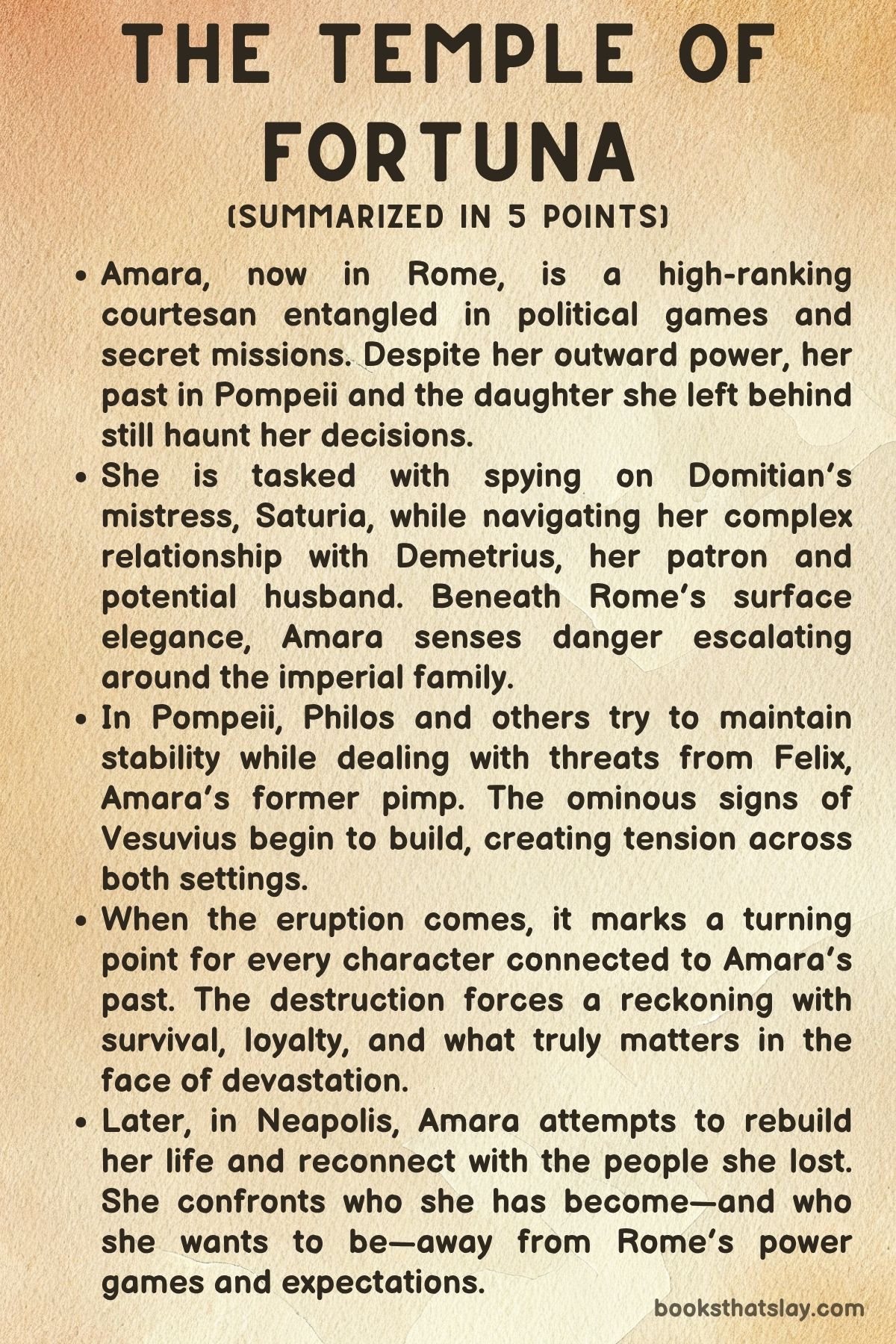

The Temple of Fortuna is the third and final novel in Elodie Harper’s Wolf Den trilogy, set in the shadow of Ancient Rome’s volatile power and Pompeii’s infamous tragedy. The story follows Amara, a once-enslaved woman who fought her way through cruelty, compromise, and sacrifice to reach the upper echelons of Roman society.

In this final chapter, Harper explores the fragility of power, the enduring scars of survival, and the resilience of love and motherhood. With emotional depth and historical precision, the novel closes Amara’s arc with fire, both literal and metaphorical, as she seeks freedom and self-definition beyond the roles imposed on her.

Summary

The story begins in Rome in the year AD 79. Amara, now living as the courtesan of the influential freedman Demetrius, enjoys a life of apparent luxury.

But her past as a prostitute in Pompeii’s Wolf Den continues to haunt her. While she navigates the dangerous social and political circles of the imperial capital, her thoughts remain anchored to her daughter, Rufina, and Rufina’s father, Philos, who both remain in Pompeii.

Through letters, Philos keeps Amara updated, but growing tension—especially threats from Amara’s manipulative former pimp, Felix—adds a constant undercurrent of fear to her life. Amara is tasked with observing Saturia, the young mistress of Domitian, brother to Emperor Titus.

Beneath Saturia’s charm and vanity lies a layer of fear that hints at deeper troubles. As Amara spends more time with her, it becomes clear that Domitian’s ambitions and temperament make him a dangerous figure.

When Saturia dies under suspicious circumstances, Amara is shaken. Her instincts tell her she was the real target, especially when a gift arrives bearing Saturia’s name and the scent of poison.

Demetrius offers to marry Amara to legally protect her, but she realizes that his offer is not born of love—it is a strategy. Though grateful, Amara understands the limits of this protection and the price it demands.

While Rome shifts under the weight of power struggles and mourning ceremonies for Emperor Vespasian, disaster strikes far away: Mount Vesuvius erupts, devastating Pompeii. The narrative cuts to Philos and Rufina as they struggle to escape the collapsing city.

Smoke, ash, fire, and confusion engulf everything. Philos rescues Rufina amid the chaos, refusing to let Felix exploit the disaster for his own gain.

Pliny the Elder, involved in rescue efforts, dies on the coast. His death symbolizes the futility of Roman structure against the raw force of nature.

In the face of destruction, status and influence become meaningless. People survive—or perish—on chance and determination.

Amara, frantic in Rome, receives only fragmented news of the eruption. With no confirmation about Philos or Rufina’s survival, she is paralyzed with grief and guilt.

She eventually travels to Neapolis, where survivors have gathered. Scouring records of the dead and injured, she finally finds Philos and Rufina—alive but changed.

Their reunion is deeply emotional but not without difficulty. Rufina, now older and wary, does not immediately embrace her mother.

Philos, too, is guarded. Amara’s time away, her choices, and the life she led in Rome have left scars, and their bond must be rebuilt.

Back in Neapolis, Amara buys a modest home and ends her relationship with Demetrius. Her former life as a courtesan and tool of political games no longer holds appeal.

She chooses to live quietly and deliberately, not as a possession, not as a role, but as herself. She begins to earn back Rufina’s trust and lays the foundation for a new kind of family.

The epilogue, set in April AD 81, shows a Rome ruled by Domitian. His reign is increasingly paranoid and violent.

Demetrius writes to Amara, warning her subtly about the growing dangers. Amara, however, has already stepped away from that world.

She visits the Temple of Fortuna—not to pray for favor, but to express gratitude. She is no longer a pawn in men’s games or a product of her past.

She has chosen her future, reclaimed her name, and found freedom not in power, but in authenticity, love, and self-worth.

Characters

Amara

Amara stands at the heart of the novel as its most dynamic and layered character. A former slave and courtesan from Pompeii, Amara begins the story in Rome, elevated to a position of influence as the mistress of Demetrius, a powerful freedman and advisor to Emperor Titus.

Yet her outward power belies a persistent vulnerability—rooted in her traumatic past and the precarious nature of her present. Her life in Rome demands constant performance: she is both a political pawn and a social observer, navigating imperial politics and gendered expectations.

Despite these constraints, Amara remains deeply emotionally connected to her daughter Rufina and former lover Philos, which continually draws her attention back to Pompeii. The eruption of Vesuvius is a literal and symbolic reckoning for Amara—forcing her to confront what she has sacrificed and what she wishes to reclaim.

By the novel’s end, Amara achieves a hard-earned independence. No longer bound to Demetrius, nor reliant on Rome’s false promises of protection, she builds a new life in Neapolis rooted in truth, maternal love, and dignity.

Her evolution is marked not just by survival but by transformation—from objectified body to autonomous soul.

Philos

Philos serves as the embodiment of loyalty, paternal devotion, and principled resistance within a corrupt world. Once a gladiator and Amara’s lover, Philos now lives in Pompeii with their daughter Rufina, trying to maintain a semblance of normalcy and protection despite lingering threats from Felix.

Philos represents a counterpoint to the manipulations and power games of Rome. He is emotionally grounded, morally consistent, and quietly heroic.

During the eruption of Vesuvius, his strength and courage are revealed in full force as he saves Rufina and others amid chaos. Unlike many Roman men in the narrative, Philos seeks no dominion over Amara.

Even after their reunion, he remains cautious—aware that her years of navigating elite circles have changed her. Their relationship is not painted in romantic idealism but in realism, shaped by trauma, time, and resilience.

Philos does not demand a return to the past but works with Amara to imagine a new future, driven by shared responsibility and enduring, if weathered, love.

Rufina

Rufina, though a child, carries immense emotional weight in the story as both a symbol of hope and a vessel of the past. She represents Amara’s most private vulnerability and deepest regret—the daughter left behind for a life of protection through distance.

Growing up under Philos’s care in Pompeii, Rufina experiences both affection and abandonment. The eruption of Vesuvius marks a literal survival but also a psychological rupture.

When she reunites with Amara in Neapolis, she is not a wide-eyed child eager for maternal embrace but someone tentative and guarded. Rufina’s wariness reflects the emotional cost of secrecy and separation.

Her character arc is subtle but poignant—revealing how children, even when silent, absorb the fractures and choices of adults. As Amara works to rebuild trust, Rufina becomes a quiet mirror, reflecting the past’s consequences and the possibility of healing.

Demetrius

Demetrius is a complex blend of protector and opportunist. As Amara’s patron and lover in Rome, he provides her with power, security, and proximity to imperial circles.

However, his affection is always filtered through the lens of politics. He offers marriage not from love but as a legal shield from Domitian’s growing menace, revealing his understanding of the transactional nature of their relationship.

At times, Demetrius appears genuinely fond of Amara, yet he fails to see her fully—dismissing her instincts, underestimating her trauma, and assuming her loyalty is fixed. His eventual letters from a Rome sliding into Domitian’s tyranny hint at regret and a muted awareness of his own limitations.

He is not a villain but a man shaped by a system that rewards self-preservation over emotional depth. Demetrius’s role is essential in highlighting the compromises women like Amara must make, and his presence emphasizes the difference between protection and partnership.

Saturia

Saturia initially appears as a frivolous and naive mistress of Domitian, but her layers are gradually revealed through her interactions with Amara. Underneath her painted exterior lies a woman deeply aware of her perilous position.

Her nervous laughter, evasive comments, and sudden openness to Amara suggest that Saturia is navigating a web of fear and abuse. Domitian’s presence looms over her life like a specter, and despite her status, she remains trapped—her beauty and youth granting her favor but not freedom.

Her friendship with Amara becomes a rare space for honesty, and in their shared moments, we see the tragic resonance of women used as pawns in male power games. Saturia’s murder—covered up with a grotesque facade of peace—serves as a brutal wake-up call for Amara.

It reveals the thin line between privilege and peril, and the way silence can become a form of survival until it’s too late. Saturia’s death is not only a narrative shock but a grim commentary on how expendable women can be in imperial politics.

Felix

Felix is the novel’s most chilling figure—a manipulator who thrives in the shadows of chaos. Once Amara’s pimp, Felix continues to exert power over her life through blackmail and threats.

He represents the enduring hand of past abuse that refuses to loosen its grip. His presence in both Rome and Pompeii functions as a reminder that freedom is never guaranteed when abusers are left unchecked.

During the eruption, rather than retreat or disappear, Felix seeks to leverage the disaster, proving his sociopathic need for control and domination. His threats against Philos and Rufina reveal a lack of any moral boundary.

Felix’s persistence emphasizes how trauma can re-emerge even in new contexts. True liberation, as the novel suggests, requires more than physical escape—it demands confronting and defeating the forces that once held sway.

Themes

Power and Survival

One of the most persistent themes in The Temple of Fortuna is the relationship between power and survival, particularly for women in the Roman Empire. Amara, the protagonist, navigates an environment dominated by male authority—emperors, patrons, pimps, and spies—where survival is often contingent on one’s ability to conform, manipulate, or quietly resist.

Early in the novel, Amara’s existence in Rome is precariously balanced between luxury and danger. Her position as Demetrius’s favored courtesan gives her access to influence and wealth, but it also exposes her to violent retribution from men like Domitian, whose power operates beyond any form of accountability.

When Amara spies for Demetrius and Pliny, she must sacrifice her comfort and safety to serve a system that continues to marginalize her. The death of Saturia, a woman who also walks this fine line between privilege and peril, demonstrates how tenuous power can be when it is not accompanied by institutional or familial protection.

The eruption of Vesuvius later serves as a dramatic leveling force. The rigid social hierarchies of Rome collapse under the weight of ash and fire.

Former gladiators, freed slaves, children, and elites are made equal in their vulnerability. This destruction becomes an ironic liberation for Amara—though terrifying, it breaks her ties to her past dependencies.

Ultimately, the novel portrays power not as a permanent structure but as a fragile system that can be upended by political tides or natural disaster. True survival comes not from climbing the ranks but from learning to recognize when to walk away from them altogether.

Freedom, Choice, and Identity

The novel charts Amara’s transformation from someone who once had little control over her body or fate into a woman who learns to assert agency over her own narrative. Her arc is deeply tied to the concept of freedom—not merely from slavery or prostitution, but freedom of identity, motherhood, and emotional truth.

Even after gaining physical freedom, Amara is still bound by invisible chains. These include political expectations, the possessiveness of Demetrius, the looming threat of Domitian, and the emotional scars of her years in the Wolf Den.

Her decision to leave Rome and its trappings of false security is significant. It is not an impulsive escape but a quiet, deliberate assertion of choice.

In Neapolis, she begins to reshape her life on her own terms—not as someone’s courtesan or asset, but as a mother and partner. She no longer survives by seduction or manipulation but by embracing honesty and love, even though it comes with uncertainty and discomfort.

Her relationship with Philos and Rufina is not idealized. Rufina’s guardedness and Philos’s caution remind readers that healing takes time.

But for the first time, Amara is not performing or hiding—she is choosing, openly, a life of simplicity, vulnerability, and dignity. Her final visit to the Temple of Fortuna reinforces this internal shift.

She no longer seeks divine intervention for personal gain. Her offering is made in gratitude, signaling that she no longer defines herself by what she lacks or fears but by the wholeness she has reclaimed.

Violence and Patriarchy

Throughout the novel, violence—physical, emotional, and sexual—serves as both a tool and consequence of patriarchal dominance. From the looming threat of Felix’s blackmail to Domitian’s controlling behavior and Saturia’s mysterious death, violence is embedded in nearly every relationship that women endure.

What is particularly stark is how normalized this violence is, especially when framed as protection or affection. Demetrius’s offer of marriage is presented as a gesture of care, but Amara recognizes it as another form of control—one that masks itself as security.

Saturia’s murder, thinly veiled as natural death, demonstrates how the public face of Rome enables violence against women to go unpunished. The trauma that Amara carries from her time as a prostitute is also portrayed not as an isolated past event but as an ongoing battle.

The men around her may shift—from masters to lovers to patrons—but the systemic imbalance of power rarely changes. However, Amara’s growing refusal to normalize these dynamics marks one of the novel’s most significant moral turning points.

Her eventual rejection of Demetrius and her decision to leave Rome are powerful. Not just because they remove her from physical danger, but because they symbolize a repudiation of a system that treats women as expendable.

The novel does not portray violence as redemptive or inevitable—it portrays it as a mechanism of oppression that must be consciously resisted. Amara’s journey is one of learning to recognize that not all chains are visible, and not all protection is love.

Motherhood and Emotional Inheritance

The theme of motherhood runs beneath the surface of the novel until it becomes central in the final chapters. Amara’s longing for Rufina is not simply a maternal instinct but a haunting reminder of everything she has lost, sacrificed, or deferred.

Her early years as a mother were shaped by desperation and secrecy. She had to separate from her daughter to protect her, even though it tore her apart.

When she reunites with Rufina after the eruption, their interaction is charged with uncertainty. Rufina is no longer a child but a survivor of catastrophe and abandonment.

She carries emotional wounds of her own, which complicates Amara’s hope for a seamless reunion. The novel treats this reunion with emotional realism: forgiveness is not automatic, and love, though present, is wary.

This portrayal adds nuance to the idea of maternal redemption—it is not about reclaiming a role but earning trust. Amara’s parenting in Neapolis is conscious and unglamorous.

She does not force affection or impose authority; instead, she listens, learns, and adapts. The novel also hints at intergenerational trauma.

Choices made in fear or under pressure can ripple forward, shaping a child’s understanding of love, safety, and trust. But Amara’s efforts to create a stable, honest environment offer a counter-narrative.

Cycles of pain can be interrupted not through dramatic gestures but through quiet, consistent presence. In this way, motherhood becomes not a second chance but a completely new beginning.