The Volcano Daughters Summary, Characters and Themes

The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera is a haunting, fiercely imaginative debut that blends historical fiction with magical realism to unearth the silenced histories of El Salvador.

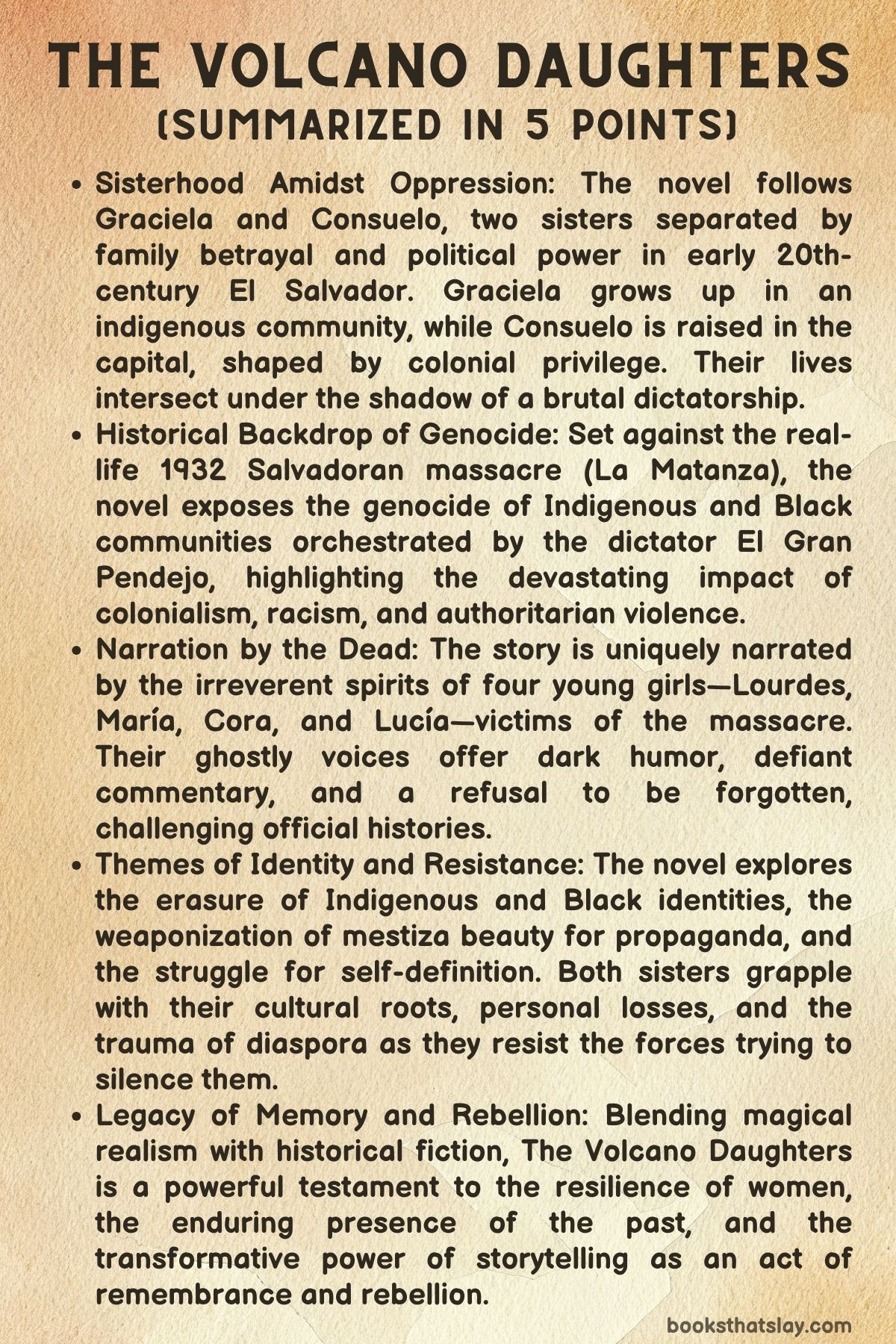

Narrated by the irreverent spirits of four girls killed during the 1932 massacre, the novel traces the lives of two sisters, Graciela and Consuelo, torn apart and reshaped by colonialism, dictatorship, and diaspora. As they navigate a brutal regime, personal loss, and exile, their stories are woven with the voices of the dead—ghosts who refuse to be forgotten. It’s a tale of resilience, memory, and the enduring power of women’s voices against the tides of history.

Summary

The Volcano Daughters unfolds against the tumultuous backdrop of early 20th-century El Salvador, spanning from 1914 to 1942. The novel is uniquely narrated by the spirits of four young girls—Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía—victims of the 1932 massacre known as La Matanza.

These spectral voices, filled with dark humor, grief, and defiance, refuse to be silenced, offering an unflinching commentary on the lives of the living and the histories often erased.

The story centers on Socorrito and her daughters, Consuelo and Graciela. Consuelo is taken from Socorrito as a young child by her wealthy, estranged father, Germán, who leaves Socorrito behind in the volcanic region of Izalco to start a new life in the capital.

Germán, an advisor to El Gran Pendejo—the dictator whose brutal regime casts a long shadow over the nation—raises Consuelo within the privileged circles of the elite.

Meanwhile, Graciela grows up with her mother in the rural, indigenous community, surrounded by close friends Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía.

Their childhood, though marked by poverty and systemic oppression, is rich with small rebellions, laughter, and the protective presence of the volcano looming over them.

When Germán dies unexpectedly, Socorrito receives a telegram summoning her and Graciela to the capital. Seeing this as an opportunity to reunite her fractured family, Socorrito embarks on the journey with hope.

However, their arrival exposes the deep chasm between Consuelo’s new life and her origins.

Consuelo, now a refined young woman, is a stranger to her own mother and sister, having been molded by the colonial ideals of beauty, art, and manners imposed by her stepmother, Perlita, a figure emblematic of the ruling class’s manipulation and cultural erasure.

Tragedy soon strikes as Socorrito mysteriously disappears—implied to be a victim of the regime’s violent suppression.

Graciela, now orphaned, is left vulnerable in the capital, where her striking mestiza beauty catches the attention of El Gran Pendejo’s inner circle.

Against her will, she becomes a symbol in the dictator’s propaganda, representing the regime’s twisted ideal of the “cosmic race”—a concept glorifying a sanitized mix of European and Indigenous heritage while erasing the identities of real Indigenous and Black communities.

While Graciela struggles under the regime’s oppressive gaze, Consuelo faces her own identity crisis. Raised with privilege yet haunted by the truths of her origins, she turns to art as both refuge and rebellion.

Their paths diverge as Consuelo navigates the contradictions of her life in the capital, while Graciela becomes quietly radicalized through her love affair with Héctor, a passionate revolutionary. Héctor’s eventual capture and execution deepen Graciela’s defiance, fueling her desire to escape the suffocating grip of the dictatorship.

The novel’s second act is marked by the horrors of La Matanza, during which over 30,000 Indigenous and Black people are slaughtered in a genocidal purge orchestrated by El Gran Pendejo.

Among the dead are Graciela’s childhood friends—Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía—whose spirits become the novel’s omnipresent narrators. Their voices are irreverent and unapologetic, mocking the official histories that attempt to erase them while fiercely preserving the memories of the lost.

Believing each other to be dead, Graciela and Consuelo flee El Salvador separately, their journeys mirroring the broader experience of diaspora.

Graciela’s path leads her through revolutionary circles and eventually to Europe during the rise of fascism, where she grapples with the echoes of colonial violence on a global scale. Consuelo, haunted by her past, becomes an acclaimed artist in exile, her work a canvas for both personal grief and cultural remembrance.

Their eventual reunion is fraught with the weight of their shared and separate traumas.

Consuelo’s tumultuous marriage to a bohemian aviator reflects her struggle to find stability, while Graciela’s mysterious death—possibly an assassination, possibly suicide—cements her as both a martyr and a myth, her true self lost amidst political propaganda and historical distortion.

Throughout the novel, the narrating spirits of Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía refuse to let the dead be forgotten.

Their commentary bridges the past and present, challenging the erasure imposed by colonialism, colorism, and authoritarian regimes. They remind us that history is not only written by the victors but also whispered by the ghosts, etched into the land, and carried in the stories passed down through generations.

The Volcano Daughters is ultimately a story of resistance—against the erasure of identity, the silencing of women, and the violence of oppressive regimes. It’s a tribute to the power of memory, the resilience of sisterhood, and the voices that rise from the ashes, refusing to be silenced.

Characters

Graciela

Graciela is a central figure in The Volcano Daughters, and her journey is defined by a struggle with identity, power, and survival under a brutal dictatorship. Raised in the volcanic region of Izalco, El Salvador, Graciela’s early life is marked by the close-knit bond she shares with her mother, Socorrito, and her friends Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía.

These friendships offer a semblance of normalcy in the face of oppressive forces, yet Graciela’s destiny is shaped by forces beyond her control. Chosen by the regime as an oracle to serve the dictator El Gran Pendejo, Graciela becomes a symbol of the “cosmic race” ideology, which romanticizes mestiza heritage.

However, this role only exacerbates her sense of alienation, as her true identity is eclipsed by the regime’s propaganda. As she becomes increasingly disillusioned with her status, she falls in love with Héctor, a revolutionary, which further exposes her to the regime’s cruelty.

The loss of her lover radicalizes her, but she is unable to escape the entangled web of politics and violence. Graciela’s life and death embody the tragic consequences of colonialism, identity erasure, and the commodification of her image.

Her eventual death, possibly a suicide or assassination, marks the loss of a voice that had long been stifled by history, but her legacy as both martyr and myth endures.

Consuelo

Consuelo’s life contrasts with Graciela’s, shaped by the privileges and isolation afforded by her father’s wealth and status in the capital. Taken from her mother at a young age, Consuelo grows up far removed from her indigenous roots and is raised in a world of luxury, disconnected from the struggles faced by her people.

Her relationship with her sister Graciela is distant and strained, as she has little memory of the life she left behind. As a product of the colonial elite, Consuelo finds herself torn between two worlds—her indigenous heritage and the privileged life in the capital.

Throughout the novel, she struggles with her identity and the role she plays in perpetuating the divide between the privileged and the oppressed. Although she becomes an artist, using her work as a means to process her trauma, Consuelo remains complicit in her privileged position.

The turbulence in her marriage, along with her eventual reconciliation with Graciela, reflects her ongoing struggle to come to terms with her past and the identity she has tried to suppress. In contrast to Graciela’s tragic fate, Consuelo’s life is marked by survival and adaptation, but she, too, is haunted by the ghosts of her homeland and her family.

Socorrito

Socorrito, the mother of Graciela and Consuelo, embodies the role of the matriarch whose strength and love anchor her family in the face of systemic violence. Her life is defined by a profound resilience against the forces that seek to tear her family apart.

A woman of the land, Socorrito’s deep connection to her indigenous heritage informs her worldview and her role as protector of her daughters. Her journey to the capital, in hopes of reclaiming her lost daughter Consuelo, marks the beginning of a harrowing battle against the oppressive elite, led by her estranged ex-husband Germán and the cruel Perlita.

Although Socorrito’s ultimate fate remains shrouded in mystery—suggesting she may have been murdered or imprisoned—her influence on her daughters, particularly Graciela, is undeniable. Socorrito represents the strength of indigenous women, whose sacrifices and perseverance in the face of exploitation and oppression often go unacknowledged by history.

El Gran Pendejo

El Gran Pendejo, the brutal dictator who rules El Salvador during the period of the novel, stands as the personification of colonial and patriarchal violence. His regime is responsible for the 1932 massacre that decimated entire communities of Indigenous and Black people, and his policies are rooted in occult beliefs, superstition, and the exploitation of the native population.

As the leader of a genocidal regime, El Gran Pendejo embodies both the power and cruelty of colonial systems, using propaganda and violence to maintain control over the country. He selects Graciela as an oracle, manipulating her into serving his political agenda, which further underscores the dehumanizing aspects of his rule.

Though he is a distant figure in terms of direct engagement with the story’s protagonists, his presence looms large over the narrative, representing the broader structures of oppression that shape the fates of the characters.

Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía

Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía, the four girls whose spirits narrate the novel, play a crucial role in framing the story within the larger context of historical trauma and memory. Although they are killed during the 1932 massacre, their voices persist beyond death, offering a lens through which the reader can witness the lives of the living characters.

The spirits’ irreverent and darkly humorous narration challenges the official histories and myths surrounding the massacre, refusing to allow the erasure of their stories. Their personalities shine through in the way they observe and critique the world, maintaining an eternal presence that ensures the voices of the oppressed are not forgotten.

They are symbolic of the resilience of memory, and their narration provides both a critique of the political system and a tribute to the forgotten victims of genocide.

Germán and Perlita

Germán and Perlita represent the oppressive colonial elite whose actions shape much of the tragic course of the story. Germán, Consuelo’s father, plays a pivotal role in separating Socorrito from her daughter, and his role as a political advisor to El Gran Pendejo makes him complicit in the regime’s cruelty.

His distant and manipulative nature reveals the moral bankruptcy of the ruling class, as he is more concerned with preserving his status and wealth than with the well-being of his family. Perlita, his wife, is a wealthy and self-serving figure who represents the entrenchment of colonial privilege.

Her manipulation of Consuelo and her indifference to Socorrito’s attempts to reclaim her daughter further highlights the elitist structures that perpetuate oppression. Together, Germán and Perlita serve as foils to the more grounded and empathetic figures of Socorrito and Graciela, embodying the forces of separation and erasure that drive much of the story’s conflict.

These characters, with their intricate relationships and struggles, serve as both personal and symbolic representations of the broader historical and social forces at play in El Salvador during the early 20th century. Each character’s story is marked by the tensions between identity, memory, and survival within a violently oppressive regime.

Themes

The Legacy of Colonialism and the Continued Erasure of Indigenous and Black Identities in Postcolonial El Salvador

One of the most powerful themes explored in The Volcano Daughters is the ongoing impact of colonialism and its corrosive effects on indigenous and Black identities. The novel delves into how colonial history shapes the present-day social and political structures in El Salvador, where wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a small elite, while the majority of the population, especially the Indigenous and Black communities, continue to suffer under systemic oppression.

This theme is poignantly symbolized in Graciela’s struggle as a mestiza woman caught between two worlds: the Indigenous roots she can’t escape and the European ideals that seek to define her. The regime’s obsession with the idea of the “cosmic race” further exemplifies the erasure of native identities, reducing a rich cultural history to a weaponized symbol that both romanticizes and marginalizes the Indigenous people of El Salvador.

The character of Graciela, as both a symbol of the regime’s idealized beauty and as an actual person with her own desires and struggles, represents the tension between colonial power structures and the people they subjugate. This theme demonstrates how history’s erasure of these identities continues to haunt the present, leaving indigenous people and their cultures invisible, even as they persist beneath the surface of society.

The Undying Struggles of Women Within the Web of Patriarchy, Political Repression, and Systemic Violence

The Volcano Daughters offers a compelling exploration of how women navigate oppressive systems of patriarchy, political repression, and violence. At the heart of this struggle are the central characters, Graciela and Consuelo, who both face different, yet equally suffocating challenges.

Graciela’s beauty and heritage make her an unwilling symbol of the dictator’s regime, trapped within the exploitation of her image, while Consuelo, raised in the capital by her wealthy father, becomes increasingly distanced from her indigenous roots. Both sisters experience the weight of being women in a patriarchal society, where their identities and destinies are constantly manipulated by men in power.

The female characters of the novel—mothers, daughters, spirits—reclaim narrative agency, serving as the bearers of memory, resistance, and survival. Their defiance comes not only in the form of overt acts of rebellion, like Graciela’s eventual support of the revolutionary cause, but also in the subtle, everyday choices that define their resilience.

The power of women to carry forward the stories of their ancestors, as well as their ability to transcend the limits imposed upon them, is a central motif that highlights how women’s experiences in such systems are always shaped by survival, perseverance, and the ever-present threat of violence.

The Power of Storytelling in Reshaping a Nation’s Identity

The blending of magical realism with historical fiction is another thematic force in The Volcano Daughters that serves to blur the boundaries between myth and reality, thus challenging conventional ways of knowing and remembering history. The narrators—Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía—are spirits who died in the 1932 massacre, yet they remain vital witnesses to the past, disrupting the official historical narrative of El Salvador.

Their voices provide both a critique and an alternative to the written history dictated by the state, emphasizing the importance of oral traditions, myth, and collective memory in reshaping a nation’s identity. By incorporating the supernatural, Balibrera doesn’t merely embellish her story with fantastical elements; instead, she uses the magical realism genre to underline the inescapability of history and the persistence of memory.

The presence of the spirits, their commentary, and their connection to the living characters affirm the belief that those silenced by violence and oppression never truly leave. Their spirits haunt the land, urging the living to remember and to act.

This theme positions storytelling and memory as acts of resistance, where the line between the factual and the mythical dissolves, and the voices of the oppressed cannot be erased from history.

The Journey of Exile and Reconciliation Across Borders

The theme of exile, diaspora, and the fragmented nature of home plays a crucial role in The Volcano Daughters. As the political climate in El Salvador grows increasingly brutal, the characters are forced into exile, navigating not only physical displacement but also an emotional journey that involves reconciling their past and present identities.

Graciela and Consuelo’s flight from their homeland represents more than just an escape from the violence of the regime; it symbolizes the larger experience of displacement faced by millions of people whose homes have been ravaged by war, genocide, or political persecution. The journey across borders—first through Central America and later to Europe—marks a continual search for a new sense of belonging.

Yet, the deeper the characters venture away from their homeland, the more they encounter a sense of alienation, as they struggle to come to terms with their past while adjusting to new environments. The theme of diaspora is tied to a longing for home, but also to the difficulty of reconciling the person they were with the person they must become.

Through their artistic endeavors and relationships, the characters reflect on the elusive nature of identity and how the process of exile is always a process of fragmentation and reinvention, where one’s sense of self is reshaped in ways that are both painful and liberating.

The Role of Memory, Death, and the Indomitable Presence of the Past in Shaping the Future of the Living

At the heart of The Volcano Daughters lies the theme of memory—how the past, particularly the experiences of those who have died, continue to exert a force on the present. Through the spirits of Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía, the novel contends that death is not an end, but rather a continuation of the fight for recognition and justice.

These spirits refuse to remain silent, and their voices reverberate through the lives of the living, reminding them that the stories of the past must never be forgotten. The juxtaposition of life and death throughout the narrative underscores the cyclical nature of violence and resistance.

As much as the political regime seeks to erase the lives of those it has murdered, the memories of the dead persist, influencing the decisions of those who survive. In this way, memory becomes a political act, an assertion of agency by those who have been silenced.

The spirits’ irreverent and playful commentary disrupts the somber nature of their existence, reminding the reader that while death can be violent and oppressive, the stories of the dead continue to illuminate and guide the future. The theme of memory thus becomes intertwined with the notion of survival—not just of the body, but of the story itself, the history that survives through generations despite efforts to erase it.

How Individual Lives Are Shaped by Larger Historical Forces

Finally, the relationship between the personal and the political is a significant theme in The Volcano Daughters. The lives of the central characters—Graciela and Consuelo—are not just shaped by their personal desires, struggles, and relationships but also by the larger political forces of their time.

From the rise of El Gran Pendejo’s brutal dictatorship to the catastrophic genocide that follows, the personal lives of the sisters are inextricably tied to the violent currents of history. Graciela’s personal journey—from an innocent, carefree girl in the volcanic hills of El Salvador to an unwilling symbol of the regime’s propaganda—is shaped by her entanglement with the political system.

Similarly, Consuelo’s struggle with her identity, as she vacillates between the privileges of her wealthy upbringing and the painful truths of her origins, is deeply affected by the political landscape. Throughout the novel, the characters’ personal stories are never separate from the political violence and oppression that surrounds them, making it impossible to view their individual experiences as isolated.

This theme underscores how deeply history and politics shape the lives of individuals, and how personal survival and resistance are tied to larger social and historical struggles.