The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez Summary, Characters and Themes

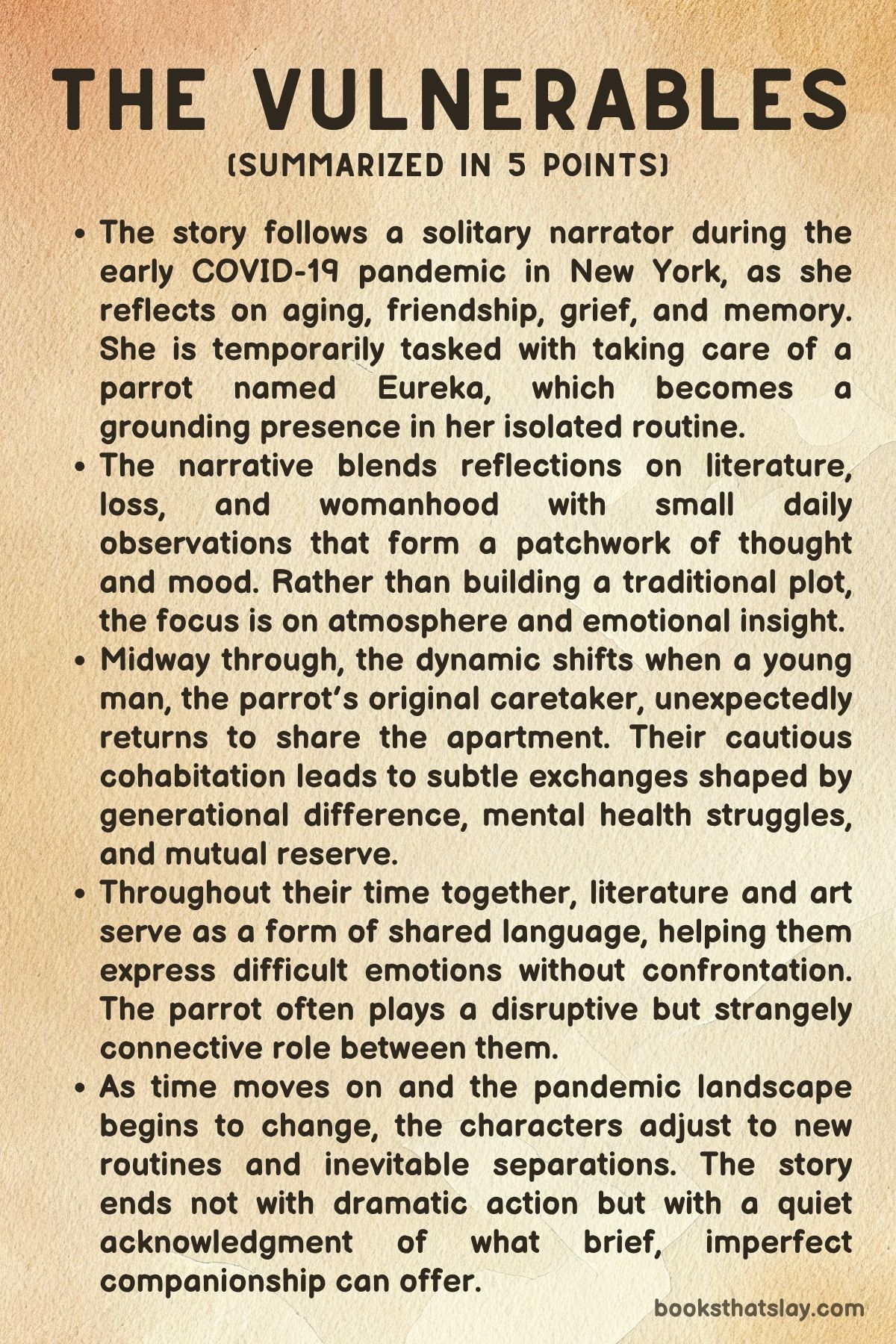

The Vulnerables is a quiet, reflective novel set during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Written in a first-person, essayistic style, it offers a deeply personal and layered narrative that blends memory, social commentary, and fleeting connection.

The unnamed narrator, an aging writer, examines the psychological weight of solitude and aging, the ache of memory, and the fragile threads of companionship—both human and animal. As she cares for a vibrant parrot named Eureka and later shares space with a younger, emotionally unstable housemate, the story captures a poignant cross-section of pandemic-era alienation and unexpected intimacy.

Nunez’s prose invites the reader into a mind that is keenly observant, subtly humorous, and searching for meaning in moments often overlooked.

Summary

The novel opens in the surreal quiet of a pandemic-stricken New York City. The narrator, an older writer who remains unnamed throughout, finds herself disoriented by the abrupt halt in daily life.

As lockdown begins, she reflects on her inability to write or read in the face of global crisis, struggling instead with grief, memory, and a sense of emotional weight that precedes even the pandemic itself. She’s invited to housesit—and more importantly, bird-sit—for a mutual acquaintance’s parrot, a green macaw named Eureka.

The bird offers a peculiar form of companionship, one that introduces rhythm and emotional texture to her otherwise muted days. Eureka is temperamental but captivating, and the narrator forms a deep attachment, finding in him a kind of surrogate presence that is both grounding and strange.

Her solitude gives way to memories of friendships, particularly with Lily, a close friend who has died. Their relationship, once filled with literary banter and personal confessions, had been shaped by shared disillusionment and independence.

Lily’s absence becomes another emotional ache the narrator carries, one among many she recounts in a stream of recollections that includes fraught childhood experiences, complicated mother-daughter dynamics, moments of romantic and sexual ambiguity, and musings on aging and beauty. These reflections are filtered through a literary consciousness—references to writers like Joan Didion, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Charles Dickens pepper her thoughts, shaping how she views both the world and herself.

As she walks through a deserted Manhattan, the natural world becomes unusually vivid. Flowers, birds, light, and scent appear more intensely, inviting meditations on transience and perception.

Her temporary refuge in a luxurious apartment, with its abundance of space and books, becomes not just a physical shelter but a space for inward travel. The narrator’s internal life becomes porous with memory, grief, and brief joy.

The apartment’s silence is then interrupted when the original bird-sitter—a young graduate student—returns unexpectedly, needing a place to stay. The narrator’s life is once again reshaped, this time by the unexpected presence of the young man.

Reserved and fragile, he is also nameless, adding to the novel’s sense of anonymity and abstraction. Their cohabitation is tentative and defined by unspoken rules, quiet gestures, and occasional conversation.

Though they never become friends in any traditional sense, a subtle relationship forms. He is haunted by past traumas, sensitive to sound and emotion, and speaks in riddled fragments about his time in psychiatric care and his deep sensitivity to the world.

His vulnerability stands in contrast to the narrator’s longer, more subdued experience of melancholy and loss. Eureka continues to play an important role in this shared life—sometimes disruptive, sometimes strangely consoling.

The parrot’s mimicry, vivid colors, and bursts of activity animate the apartment and act as a strange kind of mirror for the characters’ moods and silences. Literature and art occasionally bridge their differences, and the two housemates find brief alignment in their shared appreciation of poetry, dreams, and memory.

Yet their bond remains tentative, formed more by proximity than understanding. As the pandemic restrictions begin to lift, the small household starts to dissolve.

The young man prepares to leave, and Eureka is eventually returned to his owner. The narrator, once again alone, reflects not with sadness but with quiet acknowledgment.

Her solitude, now less raw, is tinged with gratitude for the temporary community that emerged from crisis. The book closes with a meditation on the fleeting nature of all connections—between people, animals, and moments in time.

The Vulnerables ultimately offers a tender, deeply personal portrayal of shared fragility in extraordinary times.

Characters

The Narrator

The unnamed narrator of The Vulnerables is an aging writer whose voice carries the entire novel with a reflective, essayistic sensibility. Her experience of the COVID-19 pandemic is deeply internal, marked by a profound sense of mourning and a lifelong awareness of loss.

She is a woman of intelligence and cultural depth, prone to quoting authors, referencing historical events, and layering her narrative with personal and literary allusions. Emotionally, she is somewhat detached yet quietly yearning for connection.

This yearning surfaces subtly through her attachment to the parrot Eureka and her complex feelings about aging and solitude. Her role as a caregiver—first to a bird and then in a domestic arrangement with a stranger—becomes an allegorical act of emotional endurance and minor transformation.

Her narration reveals someone accustomed to loneliness yet deeply affected by the small and ephemeral forms of companionship that emerge unexpectedly. Her psychological texture is woven from past grief, feminist consciousness, and intellectual inquiry.

Readers dwell in her layered inner life as much as her external circumstances. She is at once reserved and radically honest in her portrayal of vulnerability.

The Young Man (The Student)

The young man who enters the narrator’s life midway through The Vulnerables is a former caretaker of Eureka and becomes a temporary roommate. He is never named but is characterized through his fragility, sensitivity, and troubled emotional landscape.

A graduate student with a history of psychiatric hospitalization and PTSD, he carries with him a disquieting past. This past surfaces indirectly through anecdotes, behavior, and brief confessions.

Despite his youth, he does not embody vitality in the traditional sense. Instead, he is ghostlike, introverted, and burdened by his trauma.

His artistic inclinations and philosophical conversations with the narrator hint at a poetic, even metaphysical worldview. Yet he remains elusive and unpredictable, walking the tightrope between emotional openness and guarded withdrawal.

Their relationship is one of wary coexistence—never romantic but shaded with subtle intimacy. His presence forces the narrator to confront the unfamiliar terrain of intergenerational empathy.

This leads to moments of shared understanding, misalignment, and temporary refuge. He embodies the rawness of contemporary vulnerability, especially in younger generations navigating mental illness, cultural anxiety, and emotional displacement during crisis.

Eureka the Macaw

Though not human, Eureka the macaw occupies a central symbolic and narrative role in The Vulnerables. He is first introduced as an exotic responsibility—an inconvenience the narrator agrees to during lockdown.

Gradually, he becomes a crucial emotional tether. As a creature of beauty, mimicry, and confinement, Eureka embodies the paradoxes of companionship.

He is both burden and comfort, echo and silence, animal and emotional mirror. His daily routines give the narrator structure, his mimicry lends a surreal humor to the narrative.

His presence opens a window into the complex territory of human-animal empathy. He also becomes a mediator between the narrator and the young man, drawing them into moments of unexpected connection or conflict.

Beyond his individual personality, Eureka represents the vulnerable other—someone dependent yet vibrant, alien yet familiar. His final return to his owner marks a poignant moment of parting.

This return reinforces the novel’s meditation on temporary bonds and the fragility of affection. Eureka remains a living metaphor for beauty, limitation, and the strange companionship of crisis.

Lily

Though deceased and appearing only through memory, Lily—one of the narrator’s closest friends—is an essential character in The Vulnerables. Her presence haunts much of Part One.

She is recalled with affection, melancholy, and an aching intimacy that reveals the depth of their bond. Lily’s death is not merely a personal loss but a thematic anchor.

She allows the narrator to explore friendship, aging, sexual freedom, and the deep scars left by grief. Through Lily, the narrator examines the complexities of female friendship—its laughter, its debates, its silent contracts.

Mortality punctuates these relationships with unresolvable absence. Lily is not idealized; rather, she is remembered with raw honesty.

Her vibrancy and imperfections remain intact. Her absence leaves behind an echo that undergirds the narrator’s own sense of being emotionally untethered.

The Narrator’s Mother

The narrator’s mother appears sporadically in memory, yet she is a pivotal figure in The Vulnerables. She shapes the emotional undercurrent of the narrator’s identity.

Their relationship, as recalled, is marked by tension, disappointment, and emotional distance. The narrator’s recollections hint at a woman who was difficult to please and emotionally withholding.

She is often a source of shame or anxiety in the narrator’s formative years. These maternal memories are not just isolated flashbacks.

They are thematic reflections on inheritance, femininity, and the ways unresolved familial wounds continue to color adult consciousness. The mother’s presence in the narrative is more psychological than biographical.

She is the specter of emotional misattunement. She is the critical voice internalized and carried into later life.

Themes

Isolation and Solitude

At the heart of The Vulnerables lies the theme of isolation, examined through both external circumstance and internal experience. The novel is set during the COVID-19 pandemic, a global moment defined by enforced solitude, and it uses this backdrop to explore how people navigate the psychological terrain of being alone.

The narrator, a single, aging writer, initially enters this solitude with a sense of quiet surrender. The empty cityscape of New York becomes a metaphor for her internal world, where relationships are ghosts and the demands of daily life dissolve.

But her solitude is not monolithic; it fluctuates between comfort and desolation, between relief from social obligations and an aching awareness of absence. The arrival of Eureka the parrot subtly shifts this balance.

Though an animal, the bird brings with it the routines and responses of companionship. In Part Two, this tension is heightened with the arrival of the young man, whose presence disrupts her quiet but also opens a doorway to intimacy and shared vulnerability.

What the novel ultimately suggests is that isolation is never purely physical or emotional. It exists on a continuum shaped by memory, space, and the desire for connection.

The narrator’s solitude becomes both a mirror and a buffer. It allows her to reckon with the past while being confronted by the needs of the present.

In this way, the novel challenges readers to consider not just the experience of being alone. It asks us to reflect on the psychological architecture we build around that state to endure and understand it.

Grief and Emotional Mourning

Grief pervades The Vulnerables as an ambient force rather than a singular event. While the death of a friend named Lily is explicitly mentioned, the narrator carries with her a broader, less tangible sense of loss.

This mourning is not performative or centered around dramatic outbursts. It is instead quiet, pervasive, and deeply interior.

The narrator frequently recalls moments from her past that were not necessarily traumatic but are tinged with regret, lost opportunities, and the passage of time. These moments surface through her musings on literature, old relationships, and even the simple act of walking through an empty park.

The grief she feels is more than personal—it becomes existential. The pandemic, with its ambient threat and prolonged uncertainty, intensifies this emotional mourning, making it feel both communal and uniquely individual.

The presence of Eureka becomes a kind of balm, a living thing that offers a sense of continuity and attentiveness. These are qualities often absent in human grief rituals.

In Part Two, this emotional mourning becomes mirrored in the young man’s trauma. It suggests that different generations experience loss in dissimilar but equally valid ways.

The novel does not offer catharsis or resolution. Instead, it paints grief as a persistent companion—sometimes quiet, sometimes loud, but always present.

Nunez reflects on how mourning is not just about who or what we lose. It is about the version of ourselves that existed before the loss occurred.

Intergenerational Vulnerability

One of the novel’s most poignant themes is the exploration of vulnerability across different generations. The narrator and the young man, both forced into cohabitation due to the pandemic, represent contrasting embodiments of fragility.

The narrator’s vulnerability is shaped by years of accumulated experience—physical aging, emotional reflection, and existential fatigue. In contrast, the young man’s vulnerability is raw, immediate, and psychological.

He is a person in crisis, bearing the weight of mental health struggles and past trauma. What is compelling is how these two figures navigate their shared space without fully understanding each other, yet still manage to acknowledge each other’s humanity.

Their conversations, often stilted and elliptical, reflect this tension. There is a mutual recognition of damage and resilience, even if it is never explicitly stated.

Nunez uses this dynamic to question traditional notions of strength and weakness. The older character, though often isolated and melancholic, carries a kind of seasoned endurance, while the younger character, though physically vital, teeters on emotional collapse.

In this way, the novel dismantles age-based stereotypes. It suggests that vulnerability is not owned by any one demographic but is a universal condition expressed differently depending on life stage.

The pandemic setting amplifies this theme by forcing characters into unnatural intimacy. It requires them to confront not only each other’s needs but also their own limitations.

The resulting emotional exchanges are subtle but resonant. They reveal how even fleeting connections can momentarily bridge generational divides and make visible the fragile threads of empathy.

The Role of Animals and Nonhuman Companionship

Eureka the macaw is not just a narrative device but a profound thematic presence in The Vulnerables. The bird represents more than just an exotic pet; it becomes a symbol of routine, attachment, and a unique form of companionship that transcends human interaction.

In the early stages of the pandemic, when the narrator is unable to write, read, or even process the rapidly shifting external world, Eureka’s presence offers a kind of emotional anchor. The bird’s behavior—repeating phrases, reacting to sounds, engaging in playful or disruptive antics—brings a sense of structure and spontaneity that mimics the presence of another human without the complications that come with actual interpersonal dynamics.

This is significant because it allows the narrator to rediscover emotional connection in a non-threatening context. The parrot is never sentimentalized but is treated with respect and curiosity.

This highlights the deep and often underappreciated bond that can form between humans and animals. In Part Two, Eureka also becomes a mediator between the narrator and the young man.

The bird’s actions—especially when mimicking or interrupting—bring humor and sometimes discomfort. These moments force interaction or reflection.

Through Eureka, the novel explores how animals can mirror our emotions, disrupt our routines, and provide solace during crisis. This theme also engages with broader questions about empathy, communication, and what it means to care for another being.

Ultimately, Eureka represents a form of love that is wordless but deeply felt. It offers a different, perhaps purer, model of emotional interdependence.

Artistic and Literary Reflection

A persistent theme in The Vulnerables is the act of reflection through art and literature. This becomes a mode of survival for the narrator.

References to writers like Dickens, Joan Didion, Rilke, and Baldwin are not mere name-drops. They serve as emotional and intellectual touchstones.

In a time of uncertainty and crisis, the narrator turns to literature not to escape but to understand. Her reflections on books and writing reveal a worldview that is shaped not by ideology but by a lifelong engagement with narrative, metaphor, and memory.

She often questions the utility of literature in a time of crisis. Yet she returns to it compulsively, finding in it both solace and provocation.

This theme also connects to the narrator’s struggle with her own writing. Unable to produce work in the face of the pandemic’s paralysis, she begins to reflect on what writing means when the world outside feels so precarious.

The young man, too, shares this tendency. Though unstable, he is deeply sensitive to poetry and artistic expression.

Their exchanges about literature become a rare point of connection. They suggest that even fractured minds can find communion in shared aesthetic appreciation.

Through these reflections, the novel argues that art does not have to provide answers or resolutions. Instead, it offers a space where complex emotions—grief, uncertainty, beauty, absurdity—can coexist.

The artistic lens becomes not a retreat from reality but a way to frame and endure it. In this sense, literature becomes both the subject and the medium through which vulnerability is articulated.