The Weekend Guests Summary, Characters and Themes

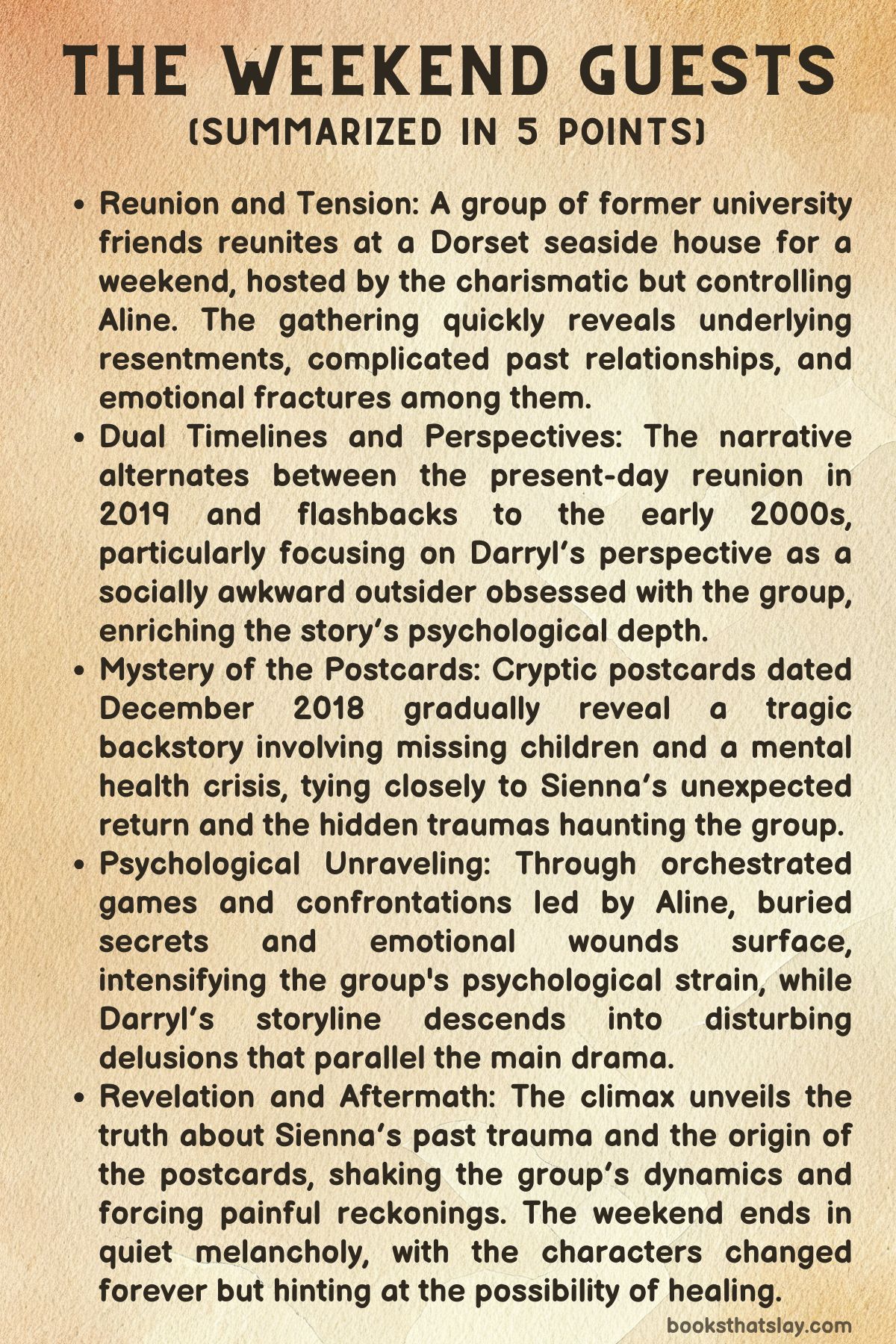

The Weekend Guests by Liza North is a contemporary psychological novel that explores the tension between memory, guilt, and the illusion of friendship. Set across two timelines—Edinburgh in the early 2000s and Dorset in 2019—it follows a group of university friends reuniting after years apart.

What begins as a glossy weekend celebration at a seaside mansion gradually becomes a crucible for past secrets and emotional reckonings. Through multiple perspectives, the novel examines the long-term consequences of youthful transgressions, fractured relationships, and buried trauma. With precise character work and layered storytelling, the book slowly unravels the lives of people who have carefully curated their adult selves while failing to escape the shadow of who they once were.

Summary

In 2019, Brandon and Aline host a weekend reunion at their luxurious home perched above the cliffs in Dorset. The occasion is meant to gather their old university circle—Michael, Rob, and their partners—for a few days of coastal leisure and nostalgic connection.

Aline, a controlling yet charismatic presence, has planned the weekend meticulously, her polished demeanor concealing the anxieties and ambitions that still define her. Among her orchestrated surprises is the arrival of Sienna, a woman who had once been part of their university life but disappeared abruptly years ago.

Her return is unexpected, and for some, unwelcome.

Michael arrives with his wife Nikki and their children, eager but cautious. The dynamics within the group begin to show strain as memories resurface.

Michael is reminded of Aline’s manipulative tendencies, but also her lingering charm. When he reconnects with Sienna, it’s not just old affection that arises but the unresolved tension of her sudden disappearance years ago.

Their private conversations reveal undercurrents of guilt and confusion that neither has fully confronted.

Rob’s world is jolted by Sienna’s reappearance. Once her lover, he is now in a relationship with Cass, a younger woman who struggles to find her place among these long-bonded friends.

Rob’s reaction to Sienna is volatile—emotional distance one moment, raw vulnerability the next. He tries to drink away his discomfort, but the chemistry between them persists.

Cass observes the subtle exchanges and emotional fissures, increasingly isolated and frustrated by Rob’s refusal to address the obvious tension.

Sienna, having left her husband and brought her daughters from San Francisco under vague pretenses, is a bundle of conflicted emotions. Her outreach to Aline had been impulsive, a grasp at reconnecting with a version of herself she had abandoned.

She is both relieved and unnerved by the invitation, unsure whether she seeks forgiveness, reconnection, or clarity. Her presence disrupts the carefully maintained façade of the reunion, particularly for Rob, whose emotional turmoil begins to leak into his relationship with Cass.

Flashbacks to 2001–2002 in Edinburgh offer critical context through the perspective of Darryl, a socially awkward and emotionally fragile PhD student who was tenuously part of the group. Living alongside Aline, Rob, and Michael, he experiences a combination of exclusion and desperate need to belong.

He develops an obsessive attachment to Aline and becomes increasingly fixated on the intimate bonds among the others. When Sienna moves into the flat, Darryl’s sense of displacement deepens.

His deteriorating mental health, underscored by his imagined relationship with a doll named Phyllis, reveals the profound alienation and trauma he’s endured, including childhood abuse and the death of his family. His only anchor is Dr.

Gemma Harris, a kind and perceptive academic supervisor who tries to set boundaries, but her empathy is ultimately not enough. In a breakdown of terrifying inevitability, Darryl strangles Gemma in a deluded fit of possessive rage.

Back in 2019, Aline and Michael each receive cryptic postcards bearing the image of Botticelli’s Madonna of the Magnificat and allusions to a long-hidden secret. The cards trigger intense anxiety, hinting at an event the group has tried to bury for nearly two decades.

That secret is gradually revealed: in 2002, during a night drive, several members of the group were involved in a hit-and-run that killed a woman named Beth Taylor. Rather than report the accident, they left the scene and buried the memory under layers of silence and rationalization.

Unknown to them, Beth had a daughter—Milly—who witnessed the accident as a child and was raised in a cold, unsympathetic environment. Years later, Milly receives a package from a dying Darryl, who had followed the group the night of the accident and kept evidence of what occurred.

Armed with this knowledge, Milly infiltrates Aline’s family under the guise of a nanny, using her position to investigate and unsettle the household from within. When her efforts to gather information fail to produce answers, she escalates her tactics: sending anonymous postcards and engaging in psychological games meant to provoke confessions.

Eventually, Milly’s need for justice erupts into open confrontation. Armed with a gun, she holds the family hostage, demanding the truth.

Aline, under pressure, admits to driving the car that killed Beth Taylor, but immediately shifts blame, framing Darryl as a disturbed and vengeful man. She manipulates the moment with chilling precision, suggesting that if Milly were to involve the police, she herself could be painted as an unstable young woman acting out of grief and delusion.

Milly is silenced but not destroyed.

Nature delivers its own form of judgment. A landslide along the cliffside consumes parts of the estate and takes with it Rob, Brandon, and Aline.

Their fate—death or survival—is left uncertain, but symbolically the land itself has reclaimed them, collapsing under the weight of long-buried truths. In contrast, the children—particularly Jimmy and Lexie—rise to the occasion.

In a tense escape sequence, they lead their siblings to safety, acting with bravery and decisiveness that their parents lack. Their courage offers a glimmer of hope, a chance that the future need not be tainted by the past.

In the final scenes, Milly is released from custody. She meets with Nikki, who extends compassion and understanding, recognizing Milly’s pain and isolation.

A final package arrives: a doll crafted by Darryl to resemble Milly. She chooses to reject it, refusing to be a symbol of trauma or revenge any longer.

Her act of disposal is quiet but powerful—an affirmation of her desire to move forward on her own terms. She no longer seeks resolution from those who wronged her, but instead begins forging a new identity, untethered from the legacy of violence and silence that defined her childhood.

Characters

Aline

Aline is the commanding and stylish host whose pristine home in Dorset becomes the gathering place for a weekend that threatens to unravel years of buried secrets. From the outset, she radiates control—curating not only the decor and social activities of the reunion but also the emotional tone of the gathering.

Her polished exterior masks an innate need to dominate her environment and the people within it. Aline sees herself as a figure of social cohesion, orchestrating moments of connection and nostalgia, but beneath her poised charisma lies manipulation, jealousy, and territoriality—particularly when it comes to her role in the group’s shared past and her unresolved feelings about Sienna.

Her attempts at intimacy are tactical rather than authentic, as seen in her awkward outreach to Nikki and her overcompensation in the form of surprises and performances. As the narrative darkens, Aline is revealed to be the driver in the fatal accident that killed Beth Taylor, a secret she attempts to bury again with icy precision.

Even when faced with confrontation, she reverts to deflection and control, displaying the emotional ruthlessness that defines her character.

Sienna

Sienna enters the narrative like a ghost from the past—her return after two decades evokes both longing and disturbance. Once a vibrant and enigmatic member of the university circle, she is now a woman weighed down by the erosion of her marriage and the burdens of motherhood.

Her reunion with the group is not merely a nostalgic impulse but a desperate attempt to reclaim a piece of her identity lost in time. Her presence destabilizes the carefully constructed facades of the others, especially Rob, with whom she had a profound and unresolved romantic entanglement.

Sienna is deeply intuitive and emotionally intelligent, yet often overwhelmed by her own guilt and the ache of the past. Her near-tragic moment with her daughter on the beach becomes a symbol of her fragile emotional state.

Haunted by the death of Beth Taylor and her own complicity in the group’s silence, she oscillates between craving forgiveness and fearing she has no right to it. Ultimately, Sienna’s journey is one of spiritual reckoning—a raw confrontation with both the literal ghosts of her past and the internal torment they left behind.

Rob

Rob is a man fractured by nostalgia, regret, and the hollowing effects of unacknowledged guilt. Charismatic in youth and sardonic in middle age, he arrives with his younger girlfriend Cass, whose presence he uses as both a shield and a distraction.

His relationship with Sienna, rekindled over the weekend, exposes the raw nerve of his unresolved emotions. Rob oscillates between deflection and longing, engaging in passive-aggressive quips while secretly drowning in remorse.

His role in the fatal accident—his silence and compliance—becomes another layer of self-betrayal. Rob’s emotional volatility is compounded by his inability to be truthful with Cass, creating a dynamic of distance and resentment.

His behavior is erratic, swinging between performative indifference and explosive confession. The landslide that physically consumes him at the climax is a fitting metaphor for the emotional landslide he has resisted for years: an internal collapse triggered by years of shame and suppression.

Michael

Michael is the embodiment of quiet guilt—unassuming on the surface but internally consumed by the long shadows of his youth. A devoted husband and father, Michael’s life has a veneer of balance, yet his eyes are constantly drawn to the cracks.

He shares a secret with Aline, underscored by the anonymous postcards that haunt him throughout the weekend. Though not as outwardly volatile as Rob or as controlling as Aline, Michael bears the psychological weight of their shared crime with quiet endurance.

His emotional depth is evident in his reaction to Sienna’s return; he processes the reunion not as a rekindling of romance but as an invitation to reflect on all that has been lost or buried. Michael’s moral compass is still intact, but it is warped by years of silence.

He does not seek redemption as much as understanding, and in his quiet confession and growing bond with Nikki, he represents the possibility of moral awareness—if not absolution.

Brandon

Brandon is Aline’s husband and an outsider to the group’s dark past, yet his role is pivotal. He is affluent, gregarious, and deeply invested in the spectacle of success—showcasing the renovated home and performing the role of genial host.

Yet his connection to Aline is laced with tension, particularly when he discovers her secret ownership of a gun, which becomes a symbol of the violence and manipulation simmering beneath their relationship. Brandon’s outburst at the shooting demonstration marks a rupture—not just in the event but in his perception of Aline and the weekend’s true purpose.

Though he does not carry the same guilt as the original group, he becomes collateral damage in their web of lies. His fate in the landslide is tragic, underscoring the devastating reach of consequences even for those who arrived at the gathering with no knowledge of what had transpired years before.

Cass

Cass is the youngest and most emotionally isolated of the group, a perceptive outsider who quickly senses the deep, unspoken history binding the others. Her relationship with Rob is strained from the beginning—she plays the part of the cheerful, tolerant girlfriend, but her observations are razor-sharp.

Cass feels the exclusion from the group’s shared language and history, and her mounting suspicion about Rob and Sienna’s affair forces her into a crisis of self-respect. Her confrontation with Rob during the shooting demonstration is not only a moment of personal betrayal but a symbolic assertion of dignity.

Cass is the only character who actively chooses to leave the gathering rather than remain trapped in its toxic nostalgia. In doing so, she claims a measure of agency and moral clarity that the others cannot.

Darryl

Darryl is the most psychologically complex and haunting figure in the narrative. A socially awkward and emotionally damaged PhD student in 2002, he enters the group’s orbit on the fringes, never fully embraced but persistently present.

His diary entries from the past reveal a mind unraveling under the weight of rejection, trauma, and delusion. He projects his longing and rage onto others, particularly Aline and Gemma, constructing elaborate inner worlds where he is either victim or savior.

His obsession with surveillance—peep-holes, dolls, and eventual violence—builds a chilling portrait of a man who felt invisible until he made himself monstrous. His murder of Gemma Harris is a tragic crescendo of untreated mental illness and emotional neglect.

In the present timeline, even from beyond the grave, Darryl remains a force of reckoning—his postcard to Milly igniting the final confrontation. He is both victim and villain, the ultimate symbol of what festers when pain is silenced.

Milly

Milly is the heart of the novel’s moral and emotional reckoning. The daughter of Beth Taylor, the woman killed in the hit-and-run, she represents the living cost of the group’s cowardice.

Raised in cold circumstances and carrying the trauma of witnessing her mother’s death, Milly embodies a quiet fury and focused resolve. Her infiltration of Aline’s household is calculated and brave, driven by a desire not just for revenge but for truth.

Milly’s psychological torment is palpable—her acts of haunting are not just theatrical but expressions of suppressed grief and unacknowledged pain. Her final confrontation with the group is devastating, made more tragic by Aline’s manipulative deflection.

Yet Milly ultimately chooses a path of healing. Her bond with Nikki and her rejection of Darryl’s symbolic doll mark the beginning of self-liberation.

Milly’s arc moves from vengeance to agency, making her not just a victim of the past but a survivor who refuses to let it define her future.

Nikki

Nikki may appear peripheral at first, but her emotional intelligence and strength make her a moral anchor in the chaotic weekend. As Michael’s wife, she is wary of Aline’s social dominance and senses the undercurrents of unease from the beginning.

Her discomfort never erupts into confrontation but is expressed through quiet observation and emotional detachment. However, Nikki’s most profound contribution comes in her interaction with Milly at the novel’s end.

In offering understanding and forgiveness, she models a compassion that stands in stark contrast to the evasiveness of the others. Nikki represents the possibility of grace—not as absolution but as a humane response to trauma.

Her presence is understated but vital, offering a glimpse of empathy in a world built on silence and evasion.

Themes

Guilt and the Persistence of the Past

In The Weekend Guests, guilt is not just a private emotion but a structural force that shapes the lives and decisions of every character. The fatal hit-and-run accident involving Beth Taylor in 2002 becomes the gravitational center around which the entire narrative orbits.

The group’s complicity in the crime and their collective decision to conceal it represent more than youthful recklessness—they are symptoms of moral evasion that reverberate well into their adult lives. Each character processes the event differently.

Aline channels her energy into control and appearances, hiding behind domestic elegance and social dominance. Michael attempts to compartmentalize, clinging to family life while quietly breaking under the weight of memory.

Rob, fractured by unresolved love and loyalty, oscillates between aggression and denial. Even those on the periphery, like Nikki and Cass, sense an absence of truth that disturbs the emotional fabric of the group.

What makes the theme of guilt so potent is how it leaks into the present, catalyzed by anonymous postcards and Sienna’s return. The Dorset setting, with its cliffs and crashing waves, mirrors the instability of lives built on lies.

The past is not a distant chapter but an active, parasitic presence, manifesting in paranoia, relational strain, and ultimately, violent reckoning. The reintroduction of Milly, Beth Taylor’s daughter, gives voice to the silenced and forgotten.

Her quest for truth is as much about reclaiming her life as it is about forcing accountability from those who tried to bury their crime. The novel portrays guilt not as a momentary feeling but as a living, corrosive legacy that cannot be fully suppressed without devastating consequences.

Control and the Performance of Power

Throughout The Weekend Guests, characters engage in subtle and overt displays of control, often under the guise of hospitality, charm, or emotional caretaking. Aline epitomizes this dynamic.

Her weekend curation—complete with strategic surprises, lavish settings, and emotional recalibrations—signals more than a desire to please. It reflects her need to dictate the narrative, to retain emotional centrality in the lives of her guests, and to orchestrate outcomes that favor her psychological comfort.

Yet this control is brittle. Her inability to fully anticipate reactions—like Sienna’s emotional volatility or Cass’s confrontational clarity—exposes the limits of manipulation.

Rob’s relationship with Cass similarly reveals control exerted through emotional withdrawal and performative indifference. He clings to irony and sarcasm as tools of deflection, even as he privately navigates a volatile mix of nostalgia and desire triggered by Sienna’s presence.

His failure to be honest with Cass or himself renders him a passive participant in the emotional warfare unfolding. Meanwhile, Sienna’s attempts at reclaiming agency—by returning, confessing, and reigniting old relationships—are met with resistance and misinterpretation.

Her vulnerability becomes a site of conflict, not resolution.

Control is also reflected in the generational divide. While the adults enact power through secrets and manipulation, the children, especially Jimmy and Lexie, exhibit a different kind of leadership: based on courage, trust, and mutual reliance.

Their escape from the collapsing house symbolizes the breaking of that generational cycle. Ultimately, the novel suggests that power built on evasion and performance is unsustainable; true strength lies in the ability to confront, accept, and rebuild.

The Fragmentation of Friendship and Memory

Friendship in The Weekend Guests is depicted not as a stable foundation but as a shifting terrain shaped by time, silence, and divergent life paths. The reunion in Dorset begins with a nostalgic longing for reconnection, but quickly fractures under the weight of unspoken grievances and distorted recollections.

University friendships, once defined by shared space and youthful exuberance, have calcified into performative roles. Brandon plays the genial host, masking his discomfort with wealth and superficiality.

Michael seeks comfort in old patterns while barely concealing his emotional exhaustion. Rob uses humor to mask resentment.

Aline treats her friendships as theatrical scripts, pre-written and stage-managed. What was once effortless camaraderie now feels like a ritualized exchange of guilt, denial, and awkward affection.

The return of Sienna acts as a disruptive force. She reminds the group of what they have chosen to forget.

Her memories don’t align neatly with the others’, and this divergence creates both intimacy and tension. The fragility of their bond is exposed when they are forced to confront the truths that memory had softened or erased.

Meanwhile, Darryl’s 2001–2002 perspective underscores this theme from the margins. Always an outsider, his longing for inclusion morphs into obsession and bitterness when denied real intimacy.

His fractured perception of friendship—as something transactional and conditional—serves as a chilling counterpoint to the group’s selective amnesia.

The novel suggests that memory, like friendship, is vulnerable to manipulation and decay. Without truth as a foundation, relationships cannot withstand the passage of time.

The emotional unraveling of the weekend proves that what binds people together may not be shared affection, but shared silence—and that silence eventually breaks.

Trauma and Mental Disintegration

Darryl’s storyline is the most harrowing depiction of trauma and its cumulative effects. His early life—marked by the death of his parents and subsequent abuse—leaves him emotionally hollow, socially anxious, and desperate for connection.

His entry into the Edinburgh flatshare represents a chance at redemption, but instead becomes another site of alienation. Unable to navigate social cues and burdened by untreated mental illness, Darryl retreats into a world of projection and fixation.

His dolls, especially Phyllis, are both comfort and curse: stand-ins for love and targets for resentment. His relationship with Dr.

Gemma Harris initially provides a sliver of hope, but when he misreads her professional kindness as romantic interest, it triggers a psychological spiral that ends in violence.

What distinguishes Darryl’s narrative is its realism. He is not a villain crafted for suspense, but a tragic figure shaped by cumulative neglect and emotional deprivation.

His final act of murder is shocking but deeply foreshadowed—a desperate assertion of control by someone who has never felt seen. The physical space he inhabits—marked by surveillance, hidden peepholes, and cluttered rooms—mirrors his mental disarray.

Even in death, Darryl’s presence lingers, particularly through his posthumous letter to Milly and the doll he leaves behind.

This theme extends into the lives of the other characters. Sienna’s emotional volatility, Michael’s guilt-ridden exhaustion, and Rob’s emotional detachment all speak to the ways trauma can take root and manifest in unexpected behaviors.

The novel presents trauma not as a single event but as a pattern—an emotional erosion that shapes how people love, hurt, and survive.

Justice, Vengeance, and Moral Ambiguity

Milly’s arc introduces a powerful meditation on justice and vengeance. As the daughter of Beth Taylor, she carries the weight of a mother lost and a childhood derailed by violence and secrecy.

Her search for the truth is motivated by more than revenge—it is a quest for identity, belonging, and moral clarity. Initially employing subtle means like nannying and anonymous postcards, Milly escalates to physical confrontation when faced with continued lies and manipulation.

Her decision to take Aline’s family hostage is portrayed not as madness, but as a desperate act by someone who has been denied justice at every turn.

The ethical complexity of her actions forces the reader to question the nature of justice. The legal system has failed her.

The adults around her offer only partial truths or self-preserving revisions. Even Aline’s confession is swiftly retracted and recontextualized to serve her narrative.

Milly’s demands for accountability are met with gaslighting and emotional manipulation. And yet, she does not emerge as a villain.

Her emotional intelligence, strategic patience, and ultimate decision not to seek further vengeance underscore her moral evolution.

The landslide that kills Aline, Rob, and Brandon functions as a symbolic intervention, a force of nature responding to the moral decay of the characters. In contrast, the children’s escape and survival offer a vision of future justice—one not bound by retribution, but by renewal.

The novel resists easy conclusions. Justice in The Weekend Guests is neither legalistic nor punitive, but messy, emotional, and deeply human.

It demands acknowledgment, even if resolution remains elusive.