The Wildest Sun Summary, Characters and Themes

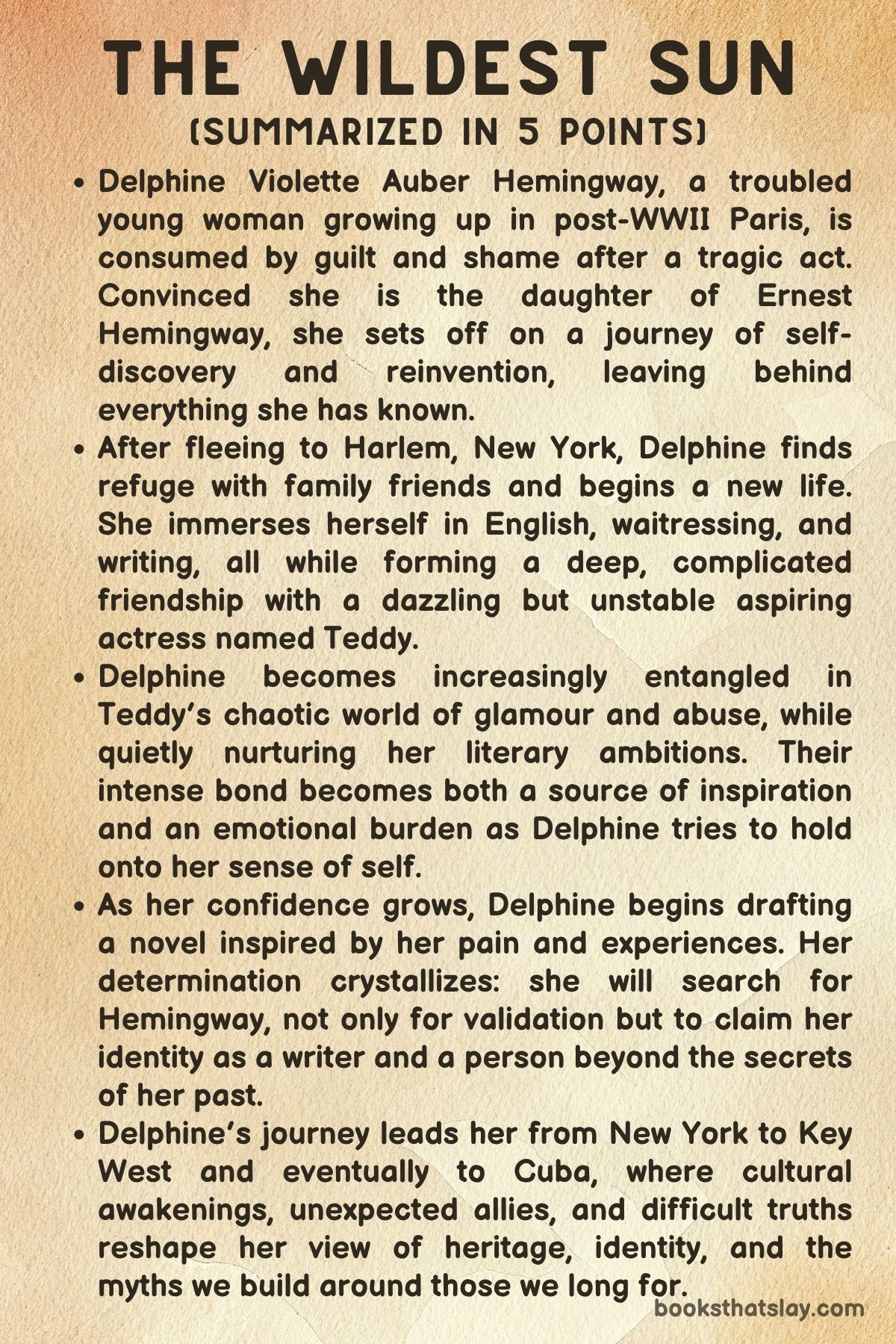

The Wildest Sun is a coming-of-age novel that follows Delphine Auber, a bold and restless young woman burdened by secrets and longing. Set in the aftermath of World War II, the story moves from postwar Paris to 1950s Harlem and on to the sun-soaked streets of Key West and Havana.

Delphine believes herself to be the illegitimate daughter of famed author Ernest Hemingway. Driven by this belief and haunted by a violent past, she sets out on a journey to find him—hoping it will also help her discover who she really is. Along the way, she forms intense relationships, wrestles with identity and ambition, and learns the cost of chasing truth.

Summary

The novel begins in 1945 Paris with Delphine Violette Auber Hemingway, a teenage girl seeking forgiveness in a chapel. She confesses to killing a woman in an emotionally charged act.

Tormented by her past and unclear parentage, she decides to leave France. She believes Ernest Hemingway is her father, based on stories her troubled mother once told.

Determined to find him and escape the shame tethered to her identity, Delphine steals money and leaves a convent behind to begin her new life.

She arrives in Harlem, New York, where she stays with Blue and Delia LaBere, friends of her late mother. While adjusting to life in America, she begins working as a waitress and taking English lessons.

Though surrounded by warmth and guidance, she feels disconnected and restless. Her only comfort is writing—something Delia encourages by gifting her a typewriter.

Through flashbacks, Delphine remembers her mother’s struggles with addiction and romantic disappointment, shaping her view of love, abandonment, and legacy.

She soon meets Teddy Dolan, an ambitious young woman dreaming of fame but trapped in a toxic relationship with an older, controlling man. Teddy introduces Delphine to New York’s nightlife and social scene, drawing her into a glittering but dangerous world.

Their friendship becomes deeply emotional, even romantic at times, but also fraught with jealousy and dependency. Delphine sees parts of her mother in Teddy—both charming and self-destructive.

As they grow closer, Delphine shares her belief that Hemingway is her father. Teddy pledges to help her find him.

Through her days spent working and writing, and her nights out with Teddy, Delphine struggles to define who she is. Her novel, The House of Pristine Sorrows, becomes an outlet for her pain and desire for meaning.

But the chaos of her relationship with Teddy begins to take a toll. They fight, reconnect, and drift again.

Delphine grows more assertive, realizing she must pursue her goal before she’s swallowed by someone else’s life.

Eventually, she sets out for Key West, Hemingway’s known home. She works in a bookstore to support herself while discreetly gathering information.

She visits Hemingway’s house but doesn’t reveal her identity. Instead, she watches, waits, and writes—torn between fantasy and fear.

When she learns Hemingway has gone to Havana, she makes a last-ditch decision to follow him, using up her savings to reach Cuba.

In Havana, Delphine meets an aging American journalist who once knew her mother. Their conversations offer painful but clarifying truths about her mother’s past and Hemingway’s possible role in it.

The journalist urges her to rethink what she’s chasing. Identity, she realizes, may not come from someone else’s acknowledgment.

Finally, Delphine meets Hemingway. The moment is anticlimactic—he is courteous but distant.

She gives him her manuscript, but there’s no grand recognition, no emotional breakthrough. Walking away, she feels let down but strangely empowered.

The man she believed would define her turns out to be just that—a man. The myth is broken, and in that breaking, Delphine sees herself more clearly.

She returns to New York ready to claim her future as a writer, no longer living in someone else’s shadow.

Her journey didn’t give her the answers she expected, but it helped her understand that the story she truly needed to tell was her own.

Characters

Delphine Violette Auber Hemingway

Delphine is the deeply introspective and tormented protagonist of the novel, whose life is shaped by trauma, secrecy, and a relentless quest for identity. From her early days in post-war Paris to her time in Harlem and eventually Cuba, she is driven by a burning belief that she is the illegitimate daughter of Ernest Hemingway.

This conviction fuels her every decision, offering both purpose and illusion. Delphine is portrayed as both fragile and fiercely determined.

She is haunted by a murder she committed and the emotional wreckage of her mother’s life. Yet she is unable to stop chasing the hope that she belongs to someone extraordinary.

Her emotional complexity is laid bare through her writing, particularly in the novel she pens within the novel, which mirrors her inner grief and fractured identity. Her relationships—with Teddy, Louise, and Hemingway—reveal her need for validation.

Ultimately, Delphine evolves. By the end, she recognizes that identity is not inherited, but constructed through self-acceptance and resilience.

Her journey is one of disillusionment and liberation. It culminates in her stepping out from Hemingway’s shadow and embracing her voice as an author.

Teddy Dolan

Teddy is a magnetic and volatile presence in Delphine’s life. She is a young American woman chasing fame while entangled in a toxic relationship.

She embodies both the glamour and decay of mid-century New York. Teddy is fueled by ambition, yet undone by emotional instability and dependency.

She quickly becomes Delphine’s closest friend and emotional counterpart. The bond they form is intense, almost symbiotic, marked by shared secrets and unspoken desires.

Teddy’s life is a performance, masking deep insecurities with charm, beauty, and recklessness. As Delphine is drawn further into Teddy’s world, she begins to see the cost of living through others’ attention.

Teddy, in turn, leans on Delphine for stability even as she self-destructs. Their relationship is one of deep affection but also unhealthy entanglement.

Ultimately, it is unsustainable. Teddy’s presence in the novel is crucial as she acts as a mirror to Delphine’s own fractured sense of self.

Blue and Delia LaBere

Blue and Delia serve as surrogate parental figures to Delphine during her time in Harlem. They are grounded, compassionate, and wise.

They represent stability and kindness in contrast to the chaos of Delphine’s past. Blue is pragmatic and reserved, while Delia is nurturing and quietly insightful.

Delia encourages Delphine to pursue her writing and gives her space to heal. Their restaurant becomes both a physical and emotional sanctuary.

It is a place where Delphine can regroup and begin her transformation. Though not central to the plot, their presence offers critical emotional grounding.

Through their unwavering support, Delphine experiences a form of care she had rarely known. This steadiness helps her begin to believe in her own potential outside of her identity as someone’s daughter.

Louise

Louise is a complex figure from Delphine’s past in Paris. She operates as both a maternal stand-in and a symbol of betrayal.

She was her mother’s close friend and later became a controlling guardian to Delphine. Louise’s relationship with Delphine is defined by power imbalance, secrecy, and emotional manipulation.

She withholds information about Delphine’s parentage and maintains an unsettling dominance over her. This dynamic shapes much of the fear and resentment Delphine harbors.

Even after Delphine escapes to New York, the memory of Louise lingers. It underscores how deeply Delphine internalized shame and uncertainty.

Louise is not portrayed as purely malicious. Instead, she represents a legacy of pain passed between women, and the tangled web of love, control, and unresolved trauma.

Delphine’s Mother

Though deceased at the start of the novel, Delphine’s mother casts a long shadow over the story. She is a once-beautiful and enigmatic woman whose life spiraled into alcoholism and regret.

She remains a mythic figure in Delphine’s mind—simultaneously admired and blamed. Her stories about Hemingway and her emotional absence contribute to Delphine’s need for clarity and connection.

She is the root of many of Delphine’s contradictions. Delphine romanticizes the past while feeling imprisoned by it, seeks fame while fearing exposure, and craves love while distrusting it.

Ultimately, the mother is portrayed not as a villain but as a broken woman. Her unfulfilled desires become a burden for her daughter to carry and transcend.

Harlan

Harlan is Teddy’s older and abusive boyfriend. He represents the dark side of ambition and codependency.

He is wealthy, controlling, and emblematic of patriarchal power. Harlan uses his resources and influence to dominate Teddy.

While he is not given a complex interior life, his presence is crucial to understanding Teddy’s entrapment. He also reveals her self-worth issues.

For Delphine, Harlan is both a threat and a cautionary symbol. He reinforces her decision to pursue independence, even at the cost of painful separation.

Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway looms large over the narrative as both a mythical figure and an absent father. To Delphine, he represents possibility, validation, and belonging.

She builds a narrative around him that sustains her through grief and uncertainty. However, the actual encounter with him is restrained and anticlimactic.

He is polite but distant. When she gives him her manuscript, he promises to read it but offers no emotional confirmation.

This moment is crucial—it forces Delphine to relinquish the fantasy. She learns to accept the ambiguity of truth.

Hemingway’s character, though minimally present, is powerful as a symbol. He embodies the illusions we build around fame, family, and legacy.

In the end, his refusal to define her allows Delphine to define herself.

Themes

The Search for Identity

At its core, The Wildest Sun is a story about a young woman’s relentless search for identity—not only in the literal sense of trying to discover whether she is the daughter of Ernest Hemingway, but also in the deeper, existential sense of understanding who she is apart from anyone else’s shadow.

Delphine begins her journey from a place of shame and alienation in post-war Paris, defined by her mother’s secrets, her undefined parentage, and a haunting crime.

She views her life as something tainted, believing that discovering her father and being acknowledged by him might offer her a clean slate or a validation of her existence. However, the trajectory of her story—from Paris to Harlem to Key West to Havana—shows how external definitions of identity are ultimately insufficient.

Delphine’s belief that her father’s legacy can redeem her becomes increasingly complicated as she starts to build a life of her own, making decisions, forming relationships, and creating art. Her writing becomes a mirror to her internal state, evolving from a means of escape to an assertion of selfhood.

This theme culminates in her meeting with Hemingway, which subverts the classic narrative of reunion. Rather than receiving confirmation or closure from him, Delphine experiences emotional ambiguity.

Yet it is in this anticlimax that her transformation is most profound. She walks away from the myth she chased, no longer dependent on her lineage to define her.

Her identity, once in fragments, begins to consolidate—not through heritage, but through her own choices, resilience, and voice.

The Burden and Liberation of Secrets

Secrets shape nearly every facet of Delphine’s life. From the earliest pages of the book, she carries the weight of having killed a woman in Paris, a crime shrouded in complex motives that include jealousy, abandonment, and self-loathing.

Her exile to New York is not only a physical escape but a psychological flight from guilt. Yet secrecy doesn’t end with this event; it continues in how she conceals her past from the people who try to help her, particularly the LaBeres and Teddy.

Even her pursuit of Hemingway is cloaked in half-truths and unspoken intentions. These hidden parts of herself erode her ability to connect fully, reinforcing her sense of isolation.

Delphine becomes skilled at performance, watching others—especially Teddy—play roles in their lives, and mimicking the same survival strategy. But secrets are corrosive, and the more she hides, the more fragmented she becomes.

Her writing, ironically, becomes the only space where she tells the truth, albeit through fiction. As her novel progresses, she begins to use it not just to express herself but to organize her inner chaos.

The journey to Key West and then Havana marks a shift: the deeper she immerses herself in environments where no one knows her past, the more she confronts the impossibility of true erasure.

The final revelation that even Hemingway cannot offer the absolution she hoped for forces her to shed the illusions she’s built. In choosing to return to New York, to publish her book and live on her own terms, Delphine replaces secrets with authorship—not just of a novel, but of her own narrative.

The Role of Art as Healing and Self-Definition

Throughout the novel, Delphine’s connection to writing is portrayed not as a career aspiration, but as a lifeline. Her earliest memories involve stories told by her mother, and over time, her belief in narrative becomes a coping mechanism.

When she receives the typewriter from the LaBeres, it marks one of the first genuine acts of recognition and support she’s experienced. Writing allows her to give form to the formless grief, confusion, and shame she carries.

The novel she writes, The House of Pristine Sorrows, is more than a piece of fiction; it becomes a container for her emotional truths. Each chapter she drafts brings her closer to articulating the parts of herself she cannot say aloud—to Teddy, to Delia, or to Hemingway.

This process also mirrors her maturation. Initially, her writing is tentative and plagued by doubt. But as her character develops, and especially during her time in Havana, the process of creating her book becomes inseparable from the process of becoming herself.

The political and social intensity of Havana, alongside her encounter with someone who knew her mother, adds depth to her understanding of human struggle and legacy—elements that enrich her manuscript.

When she finally hands her book to Hemingway, it is not as a daughter seeking approval but as an artist asserting her creation. His lukewarm response, while initially disheartening, reinforces the truth she comes to embrace.

Art is not validated by another’s recognition but by its capacity to tell the truth and to survive its creator. Writing, in the end, does not merely reflect her healing—it is the healing.

Female Friendship and the Limits of Emotional Dependence

Delphine and Teddy’s relationship is one of the most emotionally intricate aspects of the novel. What begins as an exhilarating friendship rooted in mutual fascination quickly evolves into something far more complex.

Both women are marked by abandonment, unmet emotional needs, and a hunger for meaning, and in each other they initially see not only companionship but a lifeline. Teddy, bold and performative, embodies everything Delphine thinks she wants to become: unapologetic, glamorous, and free.

But as their friendship deepens, the cracks begin to show. Teddy’s emotional volatility, exacerbated by her abusive relationship with Harlan and her struggle with addiction and ambition, reveals the instability beneath her charm.

Delphine, in trying to protect her, starts to lose herself in Teddy’s chaos. Their bond is tested repeatedly by jealousy, codependency, and unspoken expectations.

Delphine wants Teddy to save her from her loneliness, just as Teddy wants Delphine to be her anchor. This emotional entanglement becomes both a comfort and a prison.

The final parting between them is steeped in sadness but also in necessary separation. It’s only when Delphine steps away from the intensity of their friendship that she begins to regain clarity and agency.

Their relationship underscores the human need for connection but also the dangers of mistaking intimacy for identity. In the end, the friendship is meaningful, even transformative, but it is not redemptive in the way either woman hoped.

Their separation is not a failure of love but a recognition that survival sometimes requires solitude.