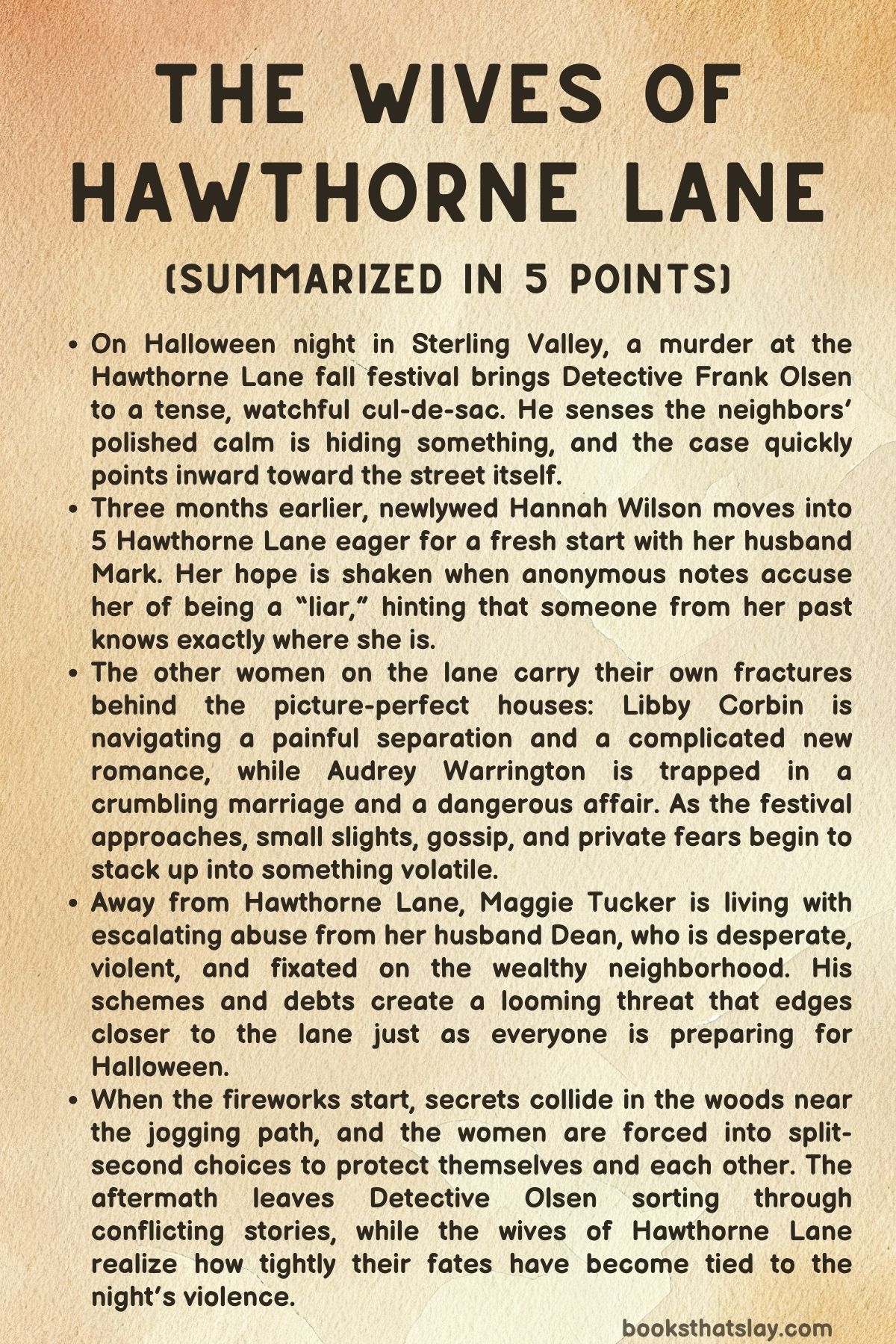

The Wives of Hawthorne Lane Summary, Characters and Themes

The Wives of Hawthorne Lane by Stephanie DeCarolis is a suburban suspense novel set in the polished, watchful cul-de-sac of Hawthorne Lane in Sterling Valley. Behind the perfect lawns and colonial facades, four women carry private fears, compromises, and secrets.

When a Halloween festival ends in a violent death on the jogging path near their homes, the neighborhood’s curated calm cracks open. The story follows these women as their marriages, pasts, and loyalties collide with the investigation, forcing them to choose between truth, survival, and each other in a place where everyone is always looking.

Summary

On Halloween night, the Sterling Valley fall festival on Hawthorne Lane erupts into chaos when sixteen-year-old Shelby Holt stumbles onto a body in the woods just beyond the street. Detective Frank Olsen arrives to find the cul-de-sac eerily still: spilled drinks, abandoned treats, and neighbors peering from windows.

He knows someone saw or heard something. The dead man is found on the jogging path in darkness near a streetlight that has been broken for weeks, and Olsen begins questioning residents who were there during the fireworks.

Three months earlier, the lane looks like a postcard. Georgina Pembrook Hawthorne, the social center of the street, announces the annual festival on the community board and starts organizing permits, vendors, and entertainment.

Around the same time, Hannah Wilson moves into 5 Hawthorne Lane with her husband Mark, an older accountant commuting to Manhattan. Hannah is young, hopeful, and eager for a fresh start after a hard childhood in foster care.

The neighbors welcome her online, and Georgina offers friendly wine and warmth when Hannah drops by with misdelivered mail. Yet Hannah’s excitement is unsettled by anonymous letters arriving from her past, each with “LIAR” printed in red.

She hides them from Mark while secretly checking a private email account, waiting for a threat she can’t name.

Libby Corbin, who lives nearby, is dealing with her own fracture. She runs a flower shop she built after years of giving up a finance career to raise her son Lucas.

Her marriage to Bill collapsed under resentment and distance, and Bill has moved on with a woman named Heather. Libby tries to hold steady for Lucas, but gossip from PTA mothers and evidence of Bill’s new relationship reopen her wounds.

She becomes obsessed with Heather, even imagining harming her when she sees Heather in public, a thought that alarms her. Wanting to reclaim her life, Libby starts talking to a man named Peter on a dating site.

Their messaging grows into a tentative new romance that feels like a lifeline.

Audrey Warrington, another Hawthorne Lane wife, lives in a different kind of loneliness. Her husband Seth is a crime novelist who spends much of his time away on tours, and when he is home he is distant and drinks heavily.

Audrey begins an affair with a charming, powerful man who makes her feel noticed — but the affair is risky and complicated. A silver tie clip left behind nearly exposes her, and Seth’s suspicion begins to grow.

When Seth’s new book is “canceled” after bad reviews and online backlash, his career collapses, and Audrey ends the affair to support him. But the man refuses to let go.

He sends obsessive texts, shows up uninvited, and eventually corners Audrey outside her office, forcing her to submit to threats. Audrey realizes she may have traded emotional neglect for real danger.

Meanwhile, beneath Georgina’s public perfection is a marriage ruled by fear. Her husband Colin Hawthorne is handsome, wealthy, and admired, but at home he is controlling and violent.

Georgina lives in constant calculation, trying to protect her children Sebastian and Christina from his moods. Colin humiliates her at a neighborhood barbecue, jokes about her spending his money, and later turns his rage on her privately.

Sebastian grows rebellious, Christina grows cautious, and Georgina’s attempts to keep peace only tighten Colin’s grip.

Away from the lane, another household circles disaster. Maggie Tucker lives on Benton Avenue with her husband Dean, who is drowning in drugs, debt, and fury at rich clients.

A dealer named Mike storms into their kitchen demanding payment for missing drugs. Maggie knows the drugs vanished because she hid them during a delivery, then discovered they were stolen.

Dean, panicked and high, decides to rob wealthy homes on Halloween, using trick-or-treating as cover. Maggie refuses, terrified, and Dean beats her badly, then reveals he has taken the cash she saved to escape.

She runs into the woods, desperate and cornered.

As Halloween approaches on Hawthorne Lane, tensions mount. Libby’s first date with Peter goes wonderfully — he is kind, attentive, and makes her feel like herself again.

She drives home choosing her own road rather than turning toward Bill’s townhouse, a small but important step forward. Audrey is trapped in fear of her former lover.

Georgina is bruised from Colin’s assaults. Hannah is rattled by more red-ink threats and by the sense that the past has found her.

On Halloween night, during the festival, Christina Hawthorne slips into the woods to meet Lucas Corbin after Colin publicly insults Lucas. Christina’s flashlight dies, she loses the path, and a man grabs her, calling her “Maggie.

” He says he has been hunting her and threatens to kill her. Christina, terrified, fights back with her Maglite, striking him in the head.

He falls. Hannah appears from the woods, shockingly calm, checks him, and urges Christina to run.

She brings Christina home, where Georgina sees blood on the flashlight and understands something terrible has happened.

Outside, Hannah finally tells Georgina the truth: she is not Hannah at all, but Melody — formerly Maggie — who escaped Dean Tucker years ago after a violent relationship. She admits that on a past Halloween she caused a car crash to stop Dean from hurting others, then watched him die in a ditch and fled.

A friend helped her get a new identity, and she rebuilt her life as Hannah Wilson. Now Dean has returned, tracked her down, and mistook Christina for her.

Hannah wants to call the police even though it could expose her false identity. Georgina insists they go back to the woods first.

Libby sees Hannah and Georgina rushing out and follows, joined by Audrey. Along the way, Hannah drops another bomb: Libby’s sweet new “Peter” is Dean Tucker, using a fake name to get close to her while hunting Hannah.

The women reach the jogging path and find Dean dead, his skull split after the blow and a fall onto rocks. Hannah is ready to tell the truth.

Georgina refuses to risk Christina being dragged through a case or blamed for killing him. Audrey reveals Colin abused her during their affair and is still dangerous.

In a rush of survival and solidarity, the women agree to frame Colin, whose violence makes him a believable suspect. They construct matching stories that erase Hannah from the night, protect Christina, and redirect blame.

Detective Olsen interviews them one by one. Libby describes rejecting a stranger who turned aggressive.

Christina says she was attacked by an unknown man and escaped. Georgina claims Colin went into the woods, returned bloodied, and refused to explain.

Audrey says she saw Colin coming from the woods with blood on him and a flashlight. The police search the Hawthorne home, find Colin asleep with swollen, bloody knuckles, and discover a bloodied jacket and flashlight in his garage.

Olsen senses gaps but arrests Colin. The neighborhood erupts into debate about whether he intended to kill Dean.

A year later, Colin is convicted of first-degree manslaughter and sentenced to ten years, bolstered by evidence that he mixed alcohol with sleeping pills and may not recall the night. Georgina sells the house and moves to California with her children; Christina thrives at UCLA, and the family begins therapy.

Audrey writes a major article about the case and domestic abuse, turning pain into public truth. Libby prepares to move with Lucas for his college future, leaving her shop to a trusted partner.

And Hannah finally tells Mark who she really is; he accepts her, choosing the life they built over the name she wore. On the next Halloween, Hawthorne Lane is quieter.

The women’s pact holds, and Hannah, pregnant and safe for now, steps into a future she once thought she’d never reach.

Characters

Hannah Wilson / Maggie Tucker / Melody

Hannah is the apparent newcomer to Hawthorne Lane, but she is built on layers of survival and reinvention. Raised in foster care and accustomed to instability, she arrives in Sterling Valley hungry for safety, belonging, and the clean-slate fantasy that the lane represents.

Yet her past is not dormant; the red-ink “LIAR” notes show how trauma keeps leaking into her present, and her reflex to hide evidence from Mark reveals how deeply secrecy has become a coping mechanism. Her real arc is about reclaiming authorship over her identity: once Melody, then Maggie trapped in abuse, now Hannah trying to live honestly.

When Dean resurfaces, Hannah’s instinct shifts from flight to confrontation, even at the cost of exposing herself, which marks her growth from a person defined by fear to one defined by choice. By the end of The Wives of Hawthorne Lane, she embodies hard-won hope: not naïve optimism, but a future she can finally stand in without running.

Mark Wilson

Mark is positioned as Hannah’s safe harbor, and his steadiness is crucial to the story’s contrast between healthy and unhealthy marriages. Older, professionally stable, and outwardly affectionate, he offers the life Hannah longs for, and he genuinely believes in their shared future.

At the same time, Mark functions as a mirror to Hannah’s internal conflict: the more trustworthy he is, the more her hidden past gnaws at her, because intimacy demands truth. He is not a dramatic force in the plot, but a moral and emotional one; his acceptance of Hannah’s confession at the end underscores the book’s argument that love rooted in respect can hold even the ugliest history.

Georgina Pembrook Hawthorne

Georgina is the social orchestrator of Hawthorne Lane, and her perfectionism is both armor and prison. She curates festivals, barbecues, and a spotless home because control is how she survives Colin’s volatile dominance.

Her outward polish hides years of escalating abuse, and the tension between her “ideal neighborhood wife” role and her private terror is one of the novel’s engines. Georgina’s maternal instincts are fierce but constrained by fear of losing her children, which Colin has weaponized against her.

Her pivotal transformation happens when she chooses collective protection over individual honesty, masterminding the cover-up to save Christina and keep Hannah safe. That decision is morally complicated, but emotionally consistent with a woman who has lived in a world where official systems never protected her.

In the aftermath, Georgina finally converts her skill at managing appearances into genuine autonomy, leaving the lane and reclaiming a life for herself and her children.

Colin Hawthorne

Colin represents the rot beneath Hawthorne Lane’s wealth: charismatic, successful, and publicly charming, but privately brutal and possessive. He uses humiliation as a control tactic, as seen at the barbecue when he belittles Georgina in front of others, and he escalates to physical violence whenever he senses disobedience.

Colin’s paranoia about being lied to is less insecurity than entitlement; he believes his family belongs to him. Even when framed for Dean’s death, the narrative makes clear that Colin’s downfall is not a random injustice but the consequence of a long pattern of harm that the neighborhood has quietly absorbed.

His conviction becomes a grim kind of poetic justice, though the book never lets that erase the ethical weight of the lie that put him there.

Christina Hawthorne

Christina begins as a typical privileged teenager chafing under parental rules, but she is quietly shaped by years of witnessing abuse. Beneath her rebellious surface is a girl trained to read danger in small shifts of tone, to keep secrets to survive, and to protect her mother emotionally even when she can’t stop the violence.

Her desire to go to UCLA is more than teenage ambition; it’s a vision of escape. On Halloween night, Christina’s confrontation with Dean becomes the moment her inherited fear flips into action.

She strikes to save herself, and that act fractures the family’s old power dynamic. Afterward, her trajectory in California signals the possibility of breaking cycles—she is not defined by what she endured, but by what she builds beyond it.

Sebastian Hawthorne

Sebastian is a volatile teenager whose anger is both personal and learned. He resents control, lashes out at Georgina, and seems reckless, but his behavior reads as the turbulence of a child raised in violence.

His protectiveness toward Christina and readiness to confront Lucas suggest a moral compass under the swagger, even if it’s expressed destructively. Sebastian’s role highlights how abuse radiates outward in families, producing not just victims but reactive, wounded adolescents struggling to find identity in chaos.

Libby Corbin

Libby is the novel’s portrait of a woman rediscovering herself after being left behind. Once oriented toward achievement, she redirected her life into motherhood and then into her flower shop, which becomes her quiet reclamation of purpose.

Bill’s departure wounds her pride and her stability, and her spiral into obsession with Heather shows how betrayal can warp even decent impulses. Yet Libby’s emotional core is resilient and ultimately generous; she wants unity for Lucas, even while aching herself.

Her near-violent fantasy toward Heather is important not because she acts on it, but because it reveals how close pain can push ordinary people to moral edges. Her relationship with Peter/Dean is a cruel twist that forces her to confront vulnerability head-on, and her choice to move forward—first emotionally with Peter before the reveal, then literally by planning a new life with Lucas—marks her as a character defined by recovery rather than collapse.

Bill Corbin

Bill is not a villain so much as a man who exited a marriage instead of repairing it. He appears polished and newly energized after separation, which is partly why Libby feels so destabilized.

His decision to buy Lucas a Mustang without consulting Libby shows his tendency to seek quick fixes and emotional shortcuts, even when they fracture trust. Yet Bill is also capable of calm honesty later, acknowledging the marriage’s decay and stepping into a more cooperative co-parenting role.

He embodies the messy middle ground of divorce: not monstrous, not heroic, just human in ways that still cause damage.

Lucas Corbin

Lucas is a teenager steeped in entitlement and angst, but he is also a kid ricocheting between two parents in emotional freefall. His demands for a car, moodiness, and casual disrespect toward Libby show typical adolescent self-centeredness amplified by family fracture.

At the same time, Lucas is not cruel by nature; his relationship with Christina and his later trajectory toward college suggest he is capable of growth once the adults around him stabilize. He functions as a reminder that children absorb marital fallout even when they pretend not to.

Audrey Warrington

Audrey is the most openly conflicted of the Hawthorne Lane wives, torn between craving desire and fearing consequence. Her affair begins in loneliness—a marriage stretched thin by Seth’s absences and self-absorption—but it veers into danger because her lover is Colin, who treats intimacy as ownership.

Audrey’s arc moves from self-indulgent escape to survival and moral urgency. When Colin’s harassment turns predatory, she becomes the story’s clearest lens on how power and violence can masquerade as romance.

Her willingness to join Georgina’s plan is partly self-protection but also solidarity, and her later publication about abuse reframes her not as a passive victim but as a woman turning private terror into public testimony.

Seth Warrington

Seth is a study in fragility disguised as talent. As a successful crime novelist, he thrives on reputation, so being “canceled” and dropped by his publisher sends him into a spiral of alcohol and paranoia.

His distance from Audrey is not purely neglect but also self-absorption; he occupies the center of his own crisis and leaves emotional debris for others to manage. Still, Seth’s breakdown humanizes him, showing a man terrified of irrelevance and failure.

His suspicion about Audrey’s infidelity is justified but also revealing: he notices her when threatened, not when she’s quietly lonely.

Dean Tucker / “Peter”

Dean is the novel’s embodiment of relentless, corrosive violence. To Hannah he is not just an abuser but a destroyer of identity, the force that once made Maggie feel she had no self beyond survival.

His criminality—drugs, debt, and plans to rob rich homes—shows a worldview built on exploitation, and his manipulation of Libby under the “Peter” persona proves how easily he weaponizes charm. Dean’s obsession with hunting Hannah is about possession, not love; he cannot tolerate her autonomy.

His death is abrupt and messy, fitting a character who lived by chaos, and it becomes the catalyst for the wives’ decisive, morally tangled alliance.

Maggie Tucker (as a former life)

Maggie is Hannah before reinvention, and she represents what prolonged abuse can do to a person’s sense of reality. She stayed with Dean through escalating harm because of isolation, fear, and the lack of a safety net after foster care.

Maggie’s Halloween-night act of leaving Dean to die is the book’s darkest moral knot: it is both a crime and a desperate rupture from captivity. This past self is not separate from Hannah but foundational to her; Hannah’s later courage makes sense only when you see what Maggie endured.

Sam

Sam is the quiet lifeline in Hannah’s backstory. He offers shelter when Maggie flees, believes her, and tries to bring in law enforcement—actions that contrast sharply with the systemic abandonment Maggie expects.

By helping her obtain a new identity, Sam becomes both savior and enabler, illustrating how survival sometimes requires morally gray help. His presence lingers as a symbol of the one friendship that was purely protective, and his folder of information represents the fragile possibility of closure that Hannah initially rejects.

Mike (the dealer)

Mike functions as the external threat from Benton Avenue, the world of debt and coercion that Dean drags into the story. He is menacing not because of complex characterization but because he represents a hierarchy of violence beyond Dean, reminding Maggie/Hannah that escape is never simple.

His predatory approach to Maggie underscores how vulnerable women become bargaining chips in criminal ecosystems.

Maggie’s husband Dean’s world (Benton Avenue context)

The Benton Avenue subplot, anchored by Maggie and Dean, widens the novel’s social scope. It shows the underside of Sterling Valley’s wealth: people consumed by resentment, addiction, and the belief that the rich are targets rather than neighbors.

This contrast reinforces the book’s theme that danger on Hawthorne Lane is not an anomaly but a convergence of hidden violences from multiple worlds.

Detective Frank Olsen

Olsen is the narrative’s procedural anchor and moral observer. He arrives to a tableau of suburban normalcy shattered by blood, and his instinct that “someone always sees something” frames the novel’s emphasis on watching, knowing, and choosing silence.

Olsen is thorough and skeptical, sensing that the wives’ synchronized testimonies don’t quite fit, but he operates within evidence, not intuition. His role highlights the limits of law in cases shaped by fear and private histories; he can catch what surfaces, but not what people bury.

Shelby Holt

Shelby is the accidental witness whose teenage recklessness collides with real horror. Her discovery of the body punctures the festival’s illusion of safety and forces the adult world into crisis mode.

She is less a developed character than a pivot point, but her presence matters because she reflects how violence on the lane spills into the lives of the young without warning.

Doreen Woodrow

Doreen is the classic peripheral observer who gives the eerie clue the system can’t ignore. Elderly, nosy in a harmless way, and attentive to neighborhood rhythms, she hears the shouting that others miss and notes the broken streetlight, which becomes symbolically important: the lane’s darkness is not sudden, it has been there “for weeks,” just unnoticed or unaddressed.

Tony Russo

Tony, the gardener, appears briefly but usefully as a figure who unsettles Audrey. His watchful, quiet presence plays into Audrey’s simmering paranoia and guilt, showing how a woman in a secret life can turn ordinary eyes into threats.

He contributes to the atmosphere of surveillance and unease that the novel sustains.

Beth (PTA mom)

Beth embodies the social predation of affluent suburbs: friendly on the surface, invasive underneath. Her gossip about Bill leaving Libby illustrates how quickly private pain becomes communal entertainment on Hawthorne Lane, and her role underscores the theme that respectability often masks cruelty.

Erica

Erica, Libby’s employee, is a small but warm counterweight to the novel’s cynicism. Her teasing and praise remind Libby that she is valued beyond her failed marriage, reinforcing Libby’s path toward self-respect.

Erica represents the everyday kindness that helps people climb out of emotional pits.

Heather Brooks

Heather is mostly seen through Libby’s obsession, which is the point: she is a real person flattened into a symbol of betrayal. Her email to Bill about his phone, and her casual presence in public, become triggers for Libby’s humiliation and rage.

Heather’s limited direct characterization keeps the focus on Libby’s internal battle—Heather is not the story’s villain, but the mirror reflecting Libby’s grief.

Sebastian and Christina’s peer circle (including Lucas)

The teens collectively represent the next generation living inside these adult fractures. Their romances, rivalries, and rebellion are not just teen drama; they are shaped by the marriages around them, showing how cycles of control, secrecy, and fear threaten to reproduce unless actively broken.

Themes

The brittle perfection of suburban respectability

Sterling Valley and Hawthorne Lane are built to look flawless: colonial houses, planned festivals, spotless kitchens, and community boards meant to signal warmth and order. Yet the story keeps showing how that surface operates like a performance that requires constant maintenance and silence about what doesn’t fit.

The fall festival itself is a staged celebration of community, but it collapses the moment violence appears, revealing how fragile the neighborhood’s idea of safety really is. Georgina embodies this tension most sharply.

Her home is praised as “perfect,” and she takes pride in being the capable organizer, cook, and hostess. But the same perfection becomes a trap, because it relies on hiding Colin’s cruelty and controlling her children’s behavior so the family looks enviable from the outside.

Audrey also lives inside that performance; she is the wife of a famous author in a beautiful house, yet she is isolated, bored, and desperate for feeling alive. Libby’s PTA circles and grocery store gossip show another side of the same system: the neighborhood polices itself through rumor, moral judgment, and a readiness to turn private pain into public spectacle.

Even Hannah’s arrival is filtered through this lens. She wants the lane to be a fresh start, and the warm welcome briefly lets her believe in that dream.

But her past cannot be erased by a nice address, and the anonymous “LIAR” notes highlight how the community’s promise of renewal is conditional. In The wives of Hawthorne lane, respectability is not harmless scenery; it is an active force that rewards conformity, punishes messiness, and encourages people to bury the truth until it erupts as catastrophe.

The murder is shocking, but the larger shock is how much violence was already present, normalized behind curated facades.

Abuse, coercion, and the hidden economies of power

Violence in the book is not only physical; it is structural and psychological, sustained by fear, dependency, and social complicity. Colin’s abuse of Georgina is the clearest example, but the theme expands beyond their marriage.

Colin humiliates Georgina in public, controls her decisions, interrogates her movements, and uses threats about the children to keep her trapped. The pattern shows how abuse is often less about isolated incidents and more about an entire system of domination.

Georgina’s memories of attempted escape, followed by Colin’s retaliation and apologies, underline the cycle that makes leaving feel impossible. Audrey’s affair with Colin introduces another dimension: coercion can grow out of desire and then turn predatory.

What begins as flirtation becomes surveillance, intimidation, and bodily threat in the alley, showing how quickly power can shift when one person believes they own another. Maggie’s past with Dean brings the theme into a different class setting, where poverty, addiction, and crime intensify the danger.

Dean’s beatings, his theft of her escape money, and his plan to rob rich homes demonstrate how abuse feeds on control of resources as much as on fists. Hannah/Maggie’s flight and reinvention reveal the long shadow of trauma: even in a new identity and a seemingly gentle marriage, she lives with hypervigilance and dread.

The women’s final pact to frame Colin is morally messy, but it grows from a shared understanding of how official systems often fail abused people. Calling the police risks exposing Hannah’s identity, blaming Christina, and returning Georgina to Colin’s reach.

Their lie becomes a survival strategy shaped by years of being disbelieved, cornered, or endangered. The wives of Hawthorne lane treats abuse as a contagious environment: it spreads through families, relationships, and institutions, and it forces victims into choices that outsiders may judge without seeing the cost of truth.

Identity, reinvention, and the price of survival

Hannah’s storyline centers on the possibility of becoming someone new, and the story refuses to make that transformation simple or clean. Her new life on Hawthorne Lane is not a fantasy of self-improvement; it is a hard-won shelter built on secrecy.

Underneath her polite neighbor role is the former Melody, then Maggie, who survived foster care, an abusive partner, and a night of fatal violence. Her reinvention is both empowerment and burden.

She is safer as “Hannah,” yet she must constantly guard that name, tear up letters, hide emails, and lie even to the husband who loves her. The “LIAR” notes are cruel not because they reveal something she doesn’t know, but because they touch the deepest fear that her survival required moral compromise.

The book keeps asking what counts as truth when truth can get you killed, imprisoned, or dragged back into harm. Libby’s identity arc mirrors this in a quieter key.

She once anchored her sense of self in motherhood and marriage, then felt hollow as Lucas grew and Bill left. Building her flower shop is a reinvention that gives her agency, but she still struggles with guilt for wanting more than the role that once defined her.

Audrey, too, is split between who she appears to be and who she feels herself becoming: a loyal wife in public, a restless woman searching for desire and recognition in private. Georgina’s eventual move to California and therapy is another form of rebirth, but it comes only after she helps engineer a false story to free herself.

In The wives of Hawthorne lane, reinvention is never presented as a neat reset. It demands secrecy, risks exposure, and often depends on other people’s silence.

Yet it is also shown as necessary for survival in a world where the past clings to you through memory, trauma, and those who refuse to let you go.

Female solidarity versus isolation under patriarchy

The four central women begin the story largely alone inside their respective houses and marriages. The neighborhood’s architecture even reinforces that loneliness: big homes set apart, windows that allow watching but not necessarily knowing.

Each woman initially tries to manage her problems privately. Libby combs through her ex-husband’s emails in isolation; Audrey hides her affair and later her fear; Georgina tidies her kitchen while bracing for Colin; Hannah buries threatening letters and tells herself she can handle it.

Their separations are not only personal but culturally trained, shaped by expectations that wives should keep families stable, keep appearances smooth, and absorb pain quietly. The turning point arrives when their private crises intersect on Halloween night, forcing them into shared space and shared risk.

What forms is not a sentimental sisterhood but a practical alliance rooted in mutual recognition. They see each other’s bruises, fear, and histories, and decide that protecting one another matters more than obeying a system that has failed them.

The plan to frame Colin is a radical act of collective agency in a landscape where male power has set the rules. It also exposes the tension inside solidarity: Georgina insists on the lie to protect Christina and herself; Hannah fears losing her new life; Audrey’s agreement is fueled by terror and anger; Libby is dragged into it by betrayal and shock.

Their unity is fragile, tested by ethical doubt and the possibility of discovery, yet it holds because it offers something none of them had alone: a path forward. The epilogue emphasizes what solidarity makes possible.

Georgina and Christina heal in therapy, Audrey speaks publicly about abuse, Libby moves on without obsession, and Hannah finally tells Mark her truth. The wives of Hawthorne lane suggests that female connection is not simply comforting; it is politically and personally life-saving in environments that thrive on keeping women separated.

Moral ambiguity and justice outside the system

The resolution hinges on a deliberate lie, and the book uses that lie to explore how justice can be both necessary and compromised. Colin is guilty of long-term terror, but not of the specific killing the women pin on him.

By standard legal measures, their act is obstruction and false testimony. Yet the narrative makes clear why the legal system feels unsafe to them.

Hannah would be exposed and possibly prosecuted for her past; Christina could be treated as a suspect rather than a victim; Georgina could face retaliation or lose her children; Audrey fears Colin’s reach and her husband’s suspicion; Libby knows how easily women’s stories are reshaped by gossip and disbelief. The women are not choosing between truth and comfort; they are choosing between truth and danger.

Detective Olsen’s unease shows that the official process senses gaps but cannot access the lived reality that produced the lie. The public debate afterward, focused on whether Colin “meant to kill,” highlights another layer: society is willing to discuss male violence only in narrow, event-based terms, not as a sustained pattern that destroys lives.

Convicting Colin becomes a form of restorative justice for harms that would otherwise remain invisible. At the same time, the book does not let the women off with simple righteousness.

Libby’s fleeting fantasy of pushing Heather into traffic, Hannah’s confession that she waited while Dean died, and the group’s careful scripting of testimony all show how trauma can push people into ethically gray terrain. The ending, where each woman gains a future, makes the reader sit with the uncomfortable idea that sometimes safety and justice arrive through imperfect means.

In The wives of Hawthorne lane, morality is not a clean scale. It is a set of choices made under pressure, shaped by unequal power, and judged differently depending on who is allowed to tell the story.