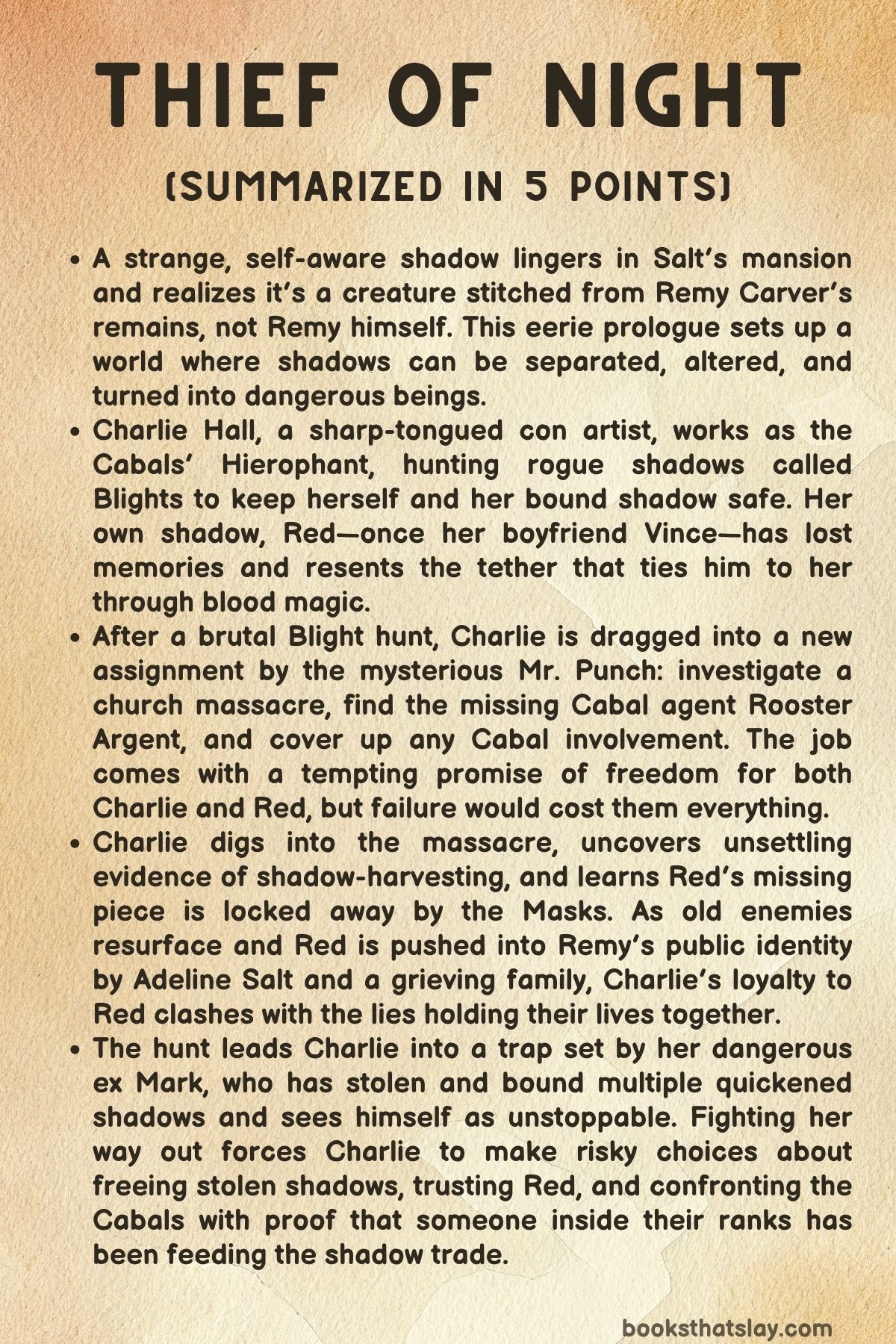

Thief of Night Summary, Characters and Themes

Thief of Night by Holly Black is a dark contemporary fantasy set in a world where shadows can be awakened, stolen, and bound to humans through painful magic. The story follows Charlie Hall, a streetwise con artist who survives by lying fast, loving hard, and staying one step ahead of people far more powerful than her.

She works for the secretive Cabals hunting vicious rogue shadows while trying to protect her sister and the shadow tethered to her—Red, once her boyfriend Vince, now something stranger and half-broken. Crime-noir grit meets eerie occult politics as Charlie uncovers who is harvesting shadows and why, while wrestling with guilt, desire, and the cost of freedom.

Summary

A strange, thinking shadow wanders the halls of Salt’s mansion at night. It clings to scraps of memory and to the name “Red,” realizing it is not truly human and not quite the person it once belonged to.

In the mansion, a girl lies sick in the library while screams rise from the basement. The shadow warns her not to look, even as it aches to be seen.

This uneasy prologue sets the tone for a world where shadows can remember, suffer, and become monsters.

Charlie Hall makes her living through scams, quick talk, and hard choices. She has recently become the Hierophant for the Cabals—shadow-magic power brokers who rule from behind polite faces.

The job forces her to hunt Blights, rogue shadows that kill and drink blood. Charlie is sent to an abandoned mill in Easthampton after reports of a Blight.

She enters alone with only a knife, flashlight, and onyx charms that can pin shadows in place. The mill is a death trap of rat bones and fresh blood.

She finds a squatter murdered minutes before. Then the Blight attacks, trying to pour itself into her body.

Charlie fights desperately, pins it with an onyx dagger, and finally destroys it with fire. Another shadow drops from above, but it is Red—her tethered shadow.

Red once was Vince, Charlie’s boyfriend, quickened into a shadow and bound to her through blood magic. The Cabals chained him and carved away part of him, creating a leash that keeps him tied to Charlie and makes her responsible for controlling him.

Red helps only on his terms, and their relationship is a mess of desire, mistrust, and old hurt.

Charlie returns to her van bleeding from the fight. Red urges stitches, but she refuses a hospital.

Instead she lets him drink her blood to strengthen their tether. The act leaves her woozy and shaken, and reminds her how thin the line is between control and craving.

In a convenience store, news of the Hatfield Cult Massacre fills the TVs: twelve people slaughtered in a church basement, drained of blood. The report triggers Charlie’s own memories of past violence and men who ruined her life.

Charlie recalls how Cabal leaders Bellamy, Malik, and Vicereine made her Hierophant for five years. They offered money and safety, but the real hook was Red.

If Charlie hunts Blights, Red stays with her; if she fails or the tether breaks, they will take him away for experiments. Charlie secretly hopes that if she can recover the missing piece of Red’s shadow, Vince might return with his memories whole.

Red, meanwhile, believes Charlie tethered him for selfish reasons, convinced she is still running a con even when she claims love.

At home, Charlie’s sister Posey is packing for yet another move, their housing unstable because of Cabal-adjacent trouble. Posey worries the Cabals are using Charlie and pushes her to develop her dormant gloamist abilities—rare magic that can command shadows.

Charlie resists, afraid of what happens when she leans into power. Their argument flares, especially when Posey talks about Red as if he’s just a dangerous tool.

Red listens, silent and insulted.

Charlie works nights at the Rapture Bar & Lounge to keep money coming in. During a chaotic dealership holiday party, a drunk customer grabs her wrist.

Red snaps into view and slams the man down, threatening him. The scene spirals into panic and filming phones, and Charlie takes an accidental punch to the face when the man swings at Red and hits her instead.

In the back room, Charlie learns a reporter wants to interview “Remy Carver”—the public identity Red must now wear. Remy was Salt’s missing heir, long presumed dead, and Red’s existence is about to be forced into that role.

Adeline Salt, Remy’s mother, demands Charlie bring Red to brunch to plan his return. Red overhears and says bluntly that he is not Remy and would rather stay dead than be made into a mask for the family’s fantasies.

Before dawn, Cabal enforcers break into Charlie’s house and drag her to meet the new puppeteer leader, Mr. Punch.

Mr. Punch speaks through stolen bodies and proves he can seize control of anyone in the room.

He gives Charlie a brutal assignment tied to the Hatfield massacre. A Cabal alterationist named Rooster Argent spoke at the church that night and vanished.

Mr. Punch wants Charlie to find out what happened, kill the Blight responsible, and erase Cabal involvement.

If she succeeds, he promises to free both her and Red from the Hierophant deal. If she fails, Red goes to Bellamy and Charlie becomes a puppet.

With no choice, she accepts.

Back at Rapture, Charlie goes to Balthazar, a shadow dealer, and asks him to teach her gloamistry. He agrees if she brings him a powerful Blight, and in return gives her a map to a hidden vault beneath the Masks’ stronghold.

Red’s missing piece is there in an onyx vial labeled “335. ” The same night, Charlie is shaken by the return of Mark Lord, an ex who once shot her and killed another man.

His conviction has been overturned. Charlie throws him out and senses old danger growing teeth again.

Charlie and Red investigate the church and the murders. Crime-scene photos show blood loss that makes no sense, victims who did not flee, and a bite mark that looks human.

Rooster appears to be a popular gloamist on TikTok, but his online life hides blackmail and Cabal orders. Breaking into his penthouse, Charlie finds recordings: Mr. Punch ordering Rooster to replace a missing “harvester” and to steal shadows for sale. A later clip ends with Rooster terrified as an unseen voice laughs.

The apartment shows signs of abandonment, suggesting Rooster is dead.

As Charlie and Posey move to a surprisingly lavish new apartment, Red asks her to cut their tether so he can meet a Blight named Rose Allaband. Charlie refuses.

Unknown to her, Rose has already contacted Red and demanded he kill someone for her. Red, trapped between old loyalties and his bond to Charlie, drugs Charlie with lorazepam, breaks the tether himself, and leaves.

Charlie wakes, tracks him, and finds a couple drained of blood. Red is fading, nearly burned out without her blood.

She stabilizes him and drives to the stronghold. Using Adeline Salt as leverage, Charlie bluffs past guards, steals vial “335,” and reunites the missing piece with Red.

His shadow steadies, and Felix stitches his torn edges. Adeline needles Charlie with claims about Salt’s victims, including Charlie’s friend Rand, deepening Charlie’s grief.

Charlie identifies the harvester as the one behind the church massacre and traces the scheme to Solaluna, a luxury retreat promising the rich a chance to awaken shadows. She tries to book a spot as “Remy Carver” but is denied.

She calls again with a fake assistant persona, determined to get inside.

Before she can act, Charlie is kidnapped and wakes bound in a filthy apartment surrounded by quickened shadows stolen and tethered to Mark Lord. Mark reveals he became a harvester under Rooster’s control, learned to hold multiple shadows, and now needs blood constantly to feed them.

He believes power is turning him into a god. He cuts Charlie with heated razors so the shadows can drink, and she struggles to stay lucid.

She offers Mark a deal: she will deliver Mr. Punch to him if Mark lets her call.

Mark agrees, greedy for revenge.

In the bathroom Charlie secretly releases a trapped shadow, sending it to Solaluna to find Red. When Mark brings her to his car for the ambush, it won’t start.

While he checks the engine, Charlie grabs a screwdriver, burns through the tether tying Mark to one shadow, and frees it. The other shadows surge at her.

Mark grabs her throat, but Red arrives with a ring of Blights he gathered after her message reached him. Charlie and Red burn through the remaining tethers, freeing Mark’s shadows into Blights.

Mark is left screaming as his stolen power turns on him, and Charlie and Red drive away.

At Solaluna, the Cabals try to punish Charlie for the released Blights.

Mr. Punch forces a new bargain: Charlie remains Hierophant and supplies him quickened shadows; Red stays free. Charlie counters by openly accusing Mr. Punch of the harvesting plan, blackmailing him into compliance. The Cabals accept.

Driving away in Red’s Porsche, Charlie is arrested for murders tied to the drifted corpse and Solaluna’s deaths. She spends a night in jail.

On TV she sees Red restored publicly as “Remy Carver,” inheriting half of Salt’s fortune beside Adeline. Red arrives at the station in that guise, signs papers to clear Charlie, and gets her released.

He returns to the mansion, leaving Charlie to wonder if freedom will always cost distance.

Charlie works through Christmas. Then Red invites her to a black-tie New Year’s Eve gala at Salt’s estate.

Adeline expects Red to leave with her after midnight, as if he were still her obedient Remy. Charlie confronts Adeline with a recording proving she watched people die to feed shadows and demands she release Red.

Adeline refuses. After midnight, Red publicly refuses Adeline’s command, claims his inheritance, and declares his autonomy.

Adeline and Fiona leave humiliated, and Red stays.

Once the guests are gone, Red takes Charlie outside, hands her a silver lighter, and asks if she wants to erase the mansion that made monsters of them all. Charlie says yes.

Together they set Salt’s house on fire and watch it burn, holding on to each other as the past collapses into ash and the possibility of a different life opens in the heat.

Characters

Charlie Hall

Charlie is the novel’s sharp-edged center: a liar, hustler, and survivor who has learned to treat truth as a tool rather than a virtue. As Hierophant for the Cabals, she lives in a constant bind between coercion and agency, hunting Blights to buy safety for herself and Posey while never forgetting that her “job” is really a leash.

What makes her compelling is the tension between her performative bravado and her buried tenderness. She insists she doesn’t want power, doesn’t want to be a gloamist, doesn’t want to command Red, yet her actions prove she wants something harder to name: control over her own life and redemption for past choices.

Her refusal to force Red is both moral rebellion and self-protective fear of what she might become if she embraces that authority. Across Thief of Night, Charlie grows less willing to bargain away pieces of herself, shifting from someone who survives by conning the system to someone who starts burning it down when it threatens the people she loves.

Red

Red is the emotional storm of the book: a quickened shadow who used to be Vince, Charlie’s boyfriend, and now exists as a patchwork Blight with missing memories and an identity crisis sharp enough to cut everyone around him. He is simultaneously intimate and alien, tethered to Charlie by blood and magic yet refusing to be owned by her or defined by Remy’s public resurrection.

Red’s inner life is dominated by contradiction. He’s protective but resentful, yearning but furious, capable of tenderness in small gestures yet quick to snarl when he senses manipulation.

His contempt for being treated as Remy is not mere stubbornness; it’s the terror of erasure, of being forced to live as someone else’s ghost. At the same time, his attraction to Charlie and his dependence on her blood tie him to the very person he most wants to distrust.

The prologue’s glimpse of his earlier consciousness shows a creature trying to stitch together selfhood from scraps, and that struggle continues through every scene: Red is a being built from violence who keeps testing whether love can be real without becoming another kind of captivity.

Posey Hall

Posey functions as Charlie’s anchor to ordinary human life, but she is no passive bystander. She is practical, alert, and willing to confront the ugliness Charlie normalizes, especially around the Cabals and Red.

Posey’s protectiveness is fierce and sometimes blunt, which makes her the moral counterweight to Charlie’s slippery pragmatism. She pushes Charlie to embrace her gloamist potential not because she craves power but because she sees how powerless Charlie is within Cabal politics.

Her sudden ability to secure a suspiciously luxurious apartment hints at hidden compromises or desperate strategies, underscoring that Posey, too, is navigating a world where survival often means deals you don’t want to admit you made. She loves Charlie enough to argue, to fear Red, and to keep moving forward anyway, embodying the theme that family can be both refuge and pressure.

Adeline Salt

Adeline is grief sharpened into control. She presents herself as Remy Carver’s protector and rightful manager, but her affection is inseparable from possession.

The years of Salt’s cruelty taught her to survive by aligning with power, and she now tries to reproduce that structure with Red, insisting on his identity as Remy because it preserves the world she understands. Her manipulation of the media and her push for legal authority over Red show her instinct to turn trauma into leverage.

Yet Adeline isn’t written as a cartoon villain; her shaken compliance when Red calls for help, her desperation at brunch, and her brittle pride reveal someone who has built her life on one relationship and cannot tolerate the idea that it might be gone. She represents the corrosive way love can curdle into entitlement when mixed with fear and privilege.

Mr. Punch

Mr. Punch is the book’s most chilling kind of power: not flamboyant evil but institutional cruelty with a polite voice.

As the new head of the puppeteers, he literally inhabits other bodies, making his dominance visible and unavoidable. He views people as objects to be piloted, corrected, or discarded, which aligns with his broader role in shadow trafficking and cover-ups.

His bargain with Charlie is classic Cabal governance: reward dangled like mercy, punishment promised like certainty. What makes him dangerous is his flexible morality and his interest in ambition.

He is willing to shift alliances, sell stolen shadows, or threaten puppethood depending on what benefits him, and he masks that opportunism under the language of order. In the end, Charlie’s ability to blackmail him doesn’t defeat him so much as prove she has learned to fight on his terrain.

Vicereine

Vicereine is a strategist who treats shadows, people, and promises as chess pieces. She is the architect of Charlie’s Hierophant situation and the one who ensures Red’s leash stays tight through the missing shadow piece.

Her power lies in calm, surgical threat: she rarely needs to raise her voice because she controls the options. Unlike Mr. Punch’s overt domination, Vicereine represents the Cabals’ long memory and procedural cruelty. Even when she seems less invested in Remy-Carver wealth drama, her warning to Charlie about the tether and her refusal to lie for Red show a woman who believes survival comes from never giving away leverage.

She embodies the idea that systems don’t need hatred to destroy people; they only need a steady hand on the rules.

Bellamy

Bellamy functions as the Cabals’ scientific predator, the one who sees a quickened shadow not as a person but as raw material. The threat of handing Red over to Bellamy is so horrifying because it implies prolonged experimentation, disassembly, and transformation into an object.

Bellamy’s presence sharpens the stakes of Charlie’s mission and proves how thin the line is between Cabal “management” and torture. When Charlie steals Red’s missing piece from Bellamy’s vault, it’s not just a plot turn; it is a rejection of Bellamy’s worldview, a small act of rescue from a future of being studied rather than lived.

Malik

Malik is less visible on-page, but his influence is central to the Hierophant bargain. He is the voice of procedural menace who tells Charlie exactly how to keep Red controlled and what will happen if she fails.

Even ousted, his earlier role shows the Cabals’ style of rule: false gentleness, clear instructions, and brutal certainty behind them. Malik represents the old guard’s belief that shadows and gloamists must be contained, and that containment is best achieved through fear disguised as advice.

Balthazar

Balthazar is a survivalist magician with the charisma of someone who has made peace with the darkness he sells. Running a shadow parlor beneath Rapture, he’s a merchant of illicit knowledge who understands that everyone wants something they can’t safely ask for.

His bargain with Charlie is pragmatic and revealing: he will teach her gloamistry only if she provides him a powerful Blight, meaning even mentorship in this world is transactional. Yet he is not purely exploitative.

He gives Charlie a map and a real lead on Red’s missing piece, suggesting a grudging respect or a sense of shared captivity under the Cabals. Balthazar stands for the gray economy of magic, where help is real but never free.

Odette

Odette is a quieter form of care in Charlie’s life, offering shelter in the back room and whiskey that is less about intoxication than steadiness. She doesn’t lecture or demand; she simply makes space for Charlie to breathe.

Her role highlights how rare uncomplicated kindness is in Charlie’s orbit. Odette is also a link to legal and social support through her lawyer contact, reminding us that not all power in the book is occult.

She functions like a small lighthouse: not enough to change the storm, but enough to keep Charlie from disappearing into it.

Malhar Iyer

Malhar is the closest the story has to an ethical scholar of shadow magic. His interview transcript with Red shows patience, curiosity, and fear that he doesn’t try to hide behind cruelty.

He treats Red as a person worth understanding, not a specimen. His skepticism about controlling multiple shadows provides a reasoned counterpoint to the Cabals’ reckless experimentation, and his lab becomes one of the few places where knowledge feels aimed at truth rather than profit.

Malhar’s presence also exposes Red’s self-awareness: Red senses Malhar’s fear and uses it, yet also seems startled by being approached without chains.

Mark Lord

Mark is the book’s human monster, not because he is uniquely evil but because he is what happens when the Cabals’ appetites spill into a desperate man’s body. Once a thief in Salt’s orbit, he becomes a harvester who steals and binds quickened shadows, feeding on blood to sustain the swarm inside him.

His godlike delusions are tragic and terrifying, rooted in the real high he feels from splitting consciousness among shadows and surviving systems that once discarded him. His cruelty toward Charlie is personal revenge and opportunistic sadism, but it is also the tantrum of someone who thinks power finally makes him untouchable.

The way his own shadows turn on him after being freed completes his arc: Mark is devoured by the very theft he built his identity around.

Rose Allaband (Rose the Blight)

Rose is a haunting mirror to Red, another quickened shadow refusing to be simplified by the narrative humans built around her. Once the alleged victim of Remy’s violence, she returns as a Blight who can bargain, threaten, and plan.

Her request that Red kill a man in two days suggests unfinished business and a shadow society with its own loyalties and contracts. Rose’s offer to murder Charlie as payment is both a genuine threat and a test of Red’s attachments.

She embodies the theme that shadowhood is not automatically innocence; freed shadows can be as morally complex and vengeful as any human.

Rosalva

Rosalva is Rose’s kin and a surprisingly principled figure among Mark’s stolen shadows. She speaks, reasons, and resists Mark’s control within the limits of her tether.

Her decision to accept responsibility for the freed shadows after Charlie burns the tethers shows an emergent ethics among Blights: they can choose care over chaos. Rosalva represents the possibility of shadow community, a hint that Blights are not only predators but also people capable of solidarity once unshackled.

The NeverMan

The NeverMan functions like a living boundary between worlds, a shadow who is watchful, eerie, and aligned with Rose’s agenda. Its presence at the window and its role in guarding Charlie emphasize how shadows can create their own hierarchies and enforcement, mirroring the Cabals in form if not in motive.

The NeverMan is less developed individually, but as a figure it deepens the sense that shadow society is organized, not random, and that Charlie is stepping into a conflict larger than a single harvester.

Archer, JonJon, Maw, and the other stolen shadows

These quickened shadows orbit Mark like hungry satellites, showing what theft does to a being’s mind. They are described through appetite and agitation, less as full personalities and more as the psychic cost of being forced into someone else’s body.

Still, their capacity to follow orders, to wait, and finally to attack Mark once freed suggests latent identity beneath their hunger. They illustrate the book’s moral logic: binding and starving shadows turns them monstrous, but freedom reopens the question of who they might be without that violence.

Rooster Argent (Dave Pugliese)

Rooster is a polished face for a rotten enterprise. As a viral gloamist influencer, he sells glamour while secretly serving Cabal shadow trafficking, lecturing cultists about quickening even as he harvests shadows for profit.

His leaked recordings reveal cowardice under pressure and complicity under authority. Rooster’s disappearance and presumed death underline the Cabals’ disposable view of their own agents.

He is not a mastermind but a middleman who believed proximity to power made him safe, and Thief of Night treats that belief as fatal.

Fiona Carver

Fiona is grief in a different key than Adeline’s: less controlling, more yearning, but still shaped by loss. She approaches Red as a resurrected grandson she wants to love loudly, perhaps to repair what she couldn’t protect before.

Her willingness to talk about Salt’s occult obsession and her regret about sending Red into that house show a woman trying to atone through affection. Red’s rejection devastates her because it collapses the story she needs to survive.

Fiona stands for the human need to hold onto a version of the dead, even when that version is not what returns.

Rand

Rand appears mostly through memory and dream, but he is one of Charlie’s deepest wounds. As her mentor in fitting in anywhere, he symbolizes the life Charlie might have had without Cabal entanglement.

Adeline’s claim that Salt fed Red on victims including Rand sharpens Charlie’s trauma into fury and clarifies why she refuses to let Red be treated as a tool again. Rand is a moral ghost haunting Charlie’s choices, pushing her toward reckoning rather than compromise.

Felix

Felix is a minor figure in page time but important in function: he stitches Red’s damaged shadow back together, representing a craft that treats shadows as bodies that can be healed instead of commodities to be sold. His work contrasts with Bellamy’s experimentation and Mark’s theft, showing that knowledge of shadows can be caretaking as well as exploitation.

Lionel Salt

Lionel Salt appears as a quickened shadow that Mark receives, a dark inheritance of the Salt family’s appetite for domination. Even without many direct scenes, Lionel’s presence inside Mark’s origin story shows how Salt’s corruption survives beyond his fall, infecting new hosts and extending the legacy of shadow abuse.

Remy Carver

Remy is both absent and everywhere, a human life that Red is forced to inhabit publicly. The Remy of memory is a boy shaped by violence, privilege, and shadow magic, tangled with Rose’s fate and Salt’s obsession.

In the present, Remy functions more as a role than a person, illustrating how identity in Thief of Night can be weaponized by families, media, and Cabals. His “return” through Red becomes a critique of how society prefers a neat resurrection story to the messy truth of what was actually lost and remade.

Themes

Identity as a contested, living thing

From the opening image of a conscious shadow paging through comics and repeating facts to keep itself from coming apart, Thief of Night treats identity as something fought over rather than discovered once and for all. Red’s existence is a constant argument between what others insist he is and what he feels himself becoming.

Adeline, Fiona, the media, and the Cabals keep trying to press him back into the mold of “Remy Carver,” because that role is useful: it stabilizes their grief, their wealth, their reputation, and their control. Red’s resistance is not polite or gradual; it’s a panicked recoil from being overwritten.

His missing memories amplify this struggle. If you can’t remember your own past, other people’s stories about you become louder, and the temptation to accept them becomes dangerous.

The prologue’s patchwork monster realizing it is not Remy but made from Remy’s remains sets the emotional rules for the whole book: a person cannot be reduced to parts, names, or other people’s nostalgia.

Charlie’s identity is also unstable, but in a different way. She calls herself a liar and has learned to survive by shifting masks—bartender, con artist, Hierophant, sister, lover, threat.

Her refusal to develop her gloamist abilities isn’t laziness; it’s fear that a new self will come with new obligations and new ways to be owned. Even her scar and her family history keep trying to define her as unlucky, disposable, or destined for disaster.

Yet she keeps choosing her own version of herself moment by moment, whether that means refusing a hospital, bargaining with Cabals, or betting everything on a risky theft for Red’s sake. The book keeps showing that identity emerges through pressure: when a character is cornered, who they are becomes visible not as a fixed label but as an action they take and repeat.

By the end, Red stepping into public power while refusing Adeline’s claims, and Charlie standing beside him as an equal rather than a handler, makes identity feel earned through conflict. It’s not about finding a “true self” hidden safely underneath; it’s about surviving long enough to insist on the right to be real.

Power, ownership, and the violence of being used

Nearly every relationship in Thief of Night is shaped by someone trying to possess someone else. Shadow magic literalizes this: a tether can bind a shadow to a body, an onyx floor can trap a person, quickening can turn a shadow into a tool, and puppeteering can hollow out a human being and make them speak for another will.

These aren’t just cool magical mechanics. They are extensions of the social world the characters live in, a world where power is hoarded through threats, secrets, and contracts that only count when the strong enforce them.

Charlie becomes Hierophant because the Cabals make the deal impossible to refuse. The offer to free her and Red is not mercy; it’s a leash with a ribbon on it, backed by the promise of torture and loss if she fails.

Mr. Punch embodies a modern, intimate authoritarianism.

He doesn’t rule through distance; he rules by crawling inside other people’s bodies.

That choice makes power feel invasive, almost domestic.

The church massacre expands this theme from personal coercion into systemic exploitation. The victims are drained, harvested, and left as evidence of how far a black-market economy of shadows can go when rich people treat magic as a luxury wellness product.

Solaluna’s retreat packages danger as self-improvement for elites, while the harvester work is done by disposable criminals like Mark, who is himself exploited and then becomes an exploiter in turn.

Red’s body and status are also a commodity. Bellamy wants him for experimentation, Adeline wants him for emotional and legal control, the Cabals want him as a bargaining chip, and the public wants him as a reassuring headline.

Even Charlie’s bond with him risks sliding into ownership, which is why their fights sting so much. Red’s repeated accusation—“you could force me”—isn’t paranoia; it’s a reminder that affection is haunted by coercive possibility in this world.

The book’s strongest moral pressure comes from asking what it means to love someone when the structure of your relationship contains a weapon. Freedom, then, isn’t a vague ideal here; it’s material.

It’s whether a tether is cut, whether a shadow is returned, whether a name is chosen rather than imposed. The mansion burning at the end is the final rejection of ownership: a house built on control and consumption is turned into ash so that no one can live inside its power again.

Trauma, memory, and survival without tidy healing

Pain in Thief of Night doesn’t sit politely in the past. It keeps flaring in the present through bodies, habits, and missing pieces.

Charlie lives with the scar from Mark’s violence, the death of Rand, the memory of Cabal deals that cost her autonomy, and the relentless fear of losing Posey. Her reflexes—lying quickly, refusing help, pushing through injury, treating danger as normal—are not quirks but survival systems shaped by repeated harm.

When she hears the news about the Hatfield massacre and gets yanked back into old terror, the scene shows how trauma is triggered by reminders that don’t ask permission.

Red’s trauma is stranger but no less real. He is the afterlife of Vince and the remains of Remy’s shadow magic, carrying holes where life should be.

The draft transcript with Malhar makes clear that being fragmented is its own kind of suffering. He doesn’t just forget; he feels himself as “discarded fragments,” and that sense of defectiveness warps how he interprets love and trust.

His volatility isn’t evidence of innate monstrosity. It’s what happens when your self is built from loss and you’re surrounded by people who prefer a version of you that’s convenient for them.

The prologue’s shadow-monster beside screaming basements suggests a lineage of abuse stretching through Salt’s house, and Red is both product and witness of that lineage.

The book is careful not to turn survival into a motivational arc. Charlie doesn’t “get over” her past in a clean way.

She keeps making messy choices—inviting Red into bed and then recoiling, keeping secrets, storming into danger she should rationally avoid—because healed people don’t always exist in stories like this, only people still living. Similarly, Red doesn’t recover into the old Vince or Remy; he becomes someone new who still carries damage.

The return of his missing shadow piece stabilizes him, but it doesn’t erase what happened while he was broken.

What makes the portrayal sharp is the way trauma shapes ethics. Charlie’s disgust and grief after Adeline’s taunts about feeding practices isn’t abstract outrage; it’s personal mourning and a refusal to normalize cruelty.

Trauma also creates solidarity. Charlie and Red’s bond intensifies not because pain is romantic, but because they recognize each other’s injuries without demanding a performance of recovery.

Survival here means continuing to choose, continue to protect, continue to resist being defined by what was done to you. The ending doesn’t offer total peace, but it offers a truer form of relief: the chance to stop living under the roof where the original harm was allowed to thrive.

Desire, trust, and the fear of intimacy

The relationship between Charlie and Red keeps moving through hunger, recoil, tenderness, and anger, not in a cute will-they-won’t-they rhythm but in the logic of two people who can’t stop needing each other and also can’t stop fearing what need might cost. Desire in Thief of Night is physical—blood drinking makes Charlie dizzy and aroused, and Red admits he wants her—but it is never simple pleasure.

It’s tied to the tether, to control, to the possibility of exploitation. The scenes where Red feeds from Charlie’s wound are both intimate and unsettling because they dramatize how care can resemble consumption.

She offers him blood to keep him stable, but doing so risks turning her into a resource he depends on. Meanwhile, his refusal to be commanded is also a refusal to let desire be recast as obligation.

Trust is equally unstable. Charlie’s entire skill set is built on deception.

Red knows this and reads her affection as a potential con. His skepticism is not just bitterness; it’s a rational response to a world where tethering, quickening, and puppeteering are common.

At the same time, Charlie genuinely doesn’t want to force him, which means she is trying to invent a kind of trust that her environment doesn’t support. Their arguments—about whether she tethered him out of love, whether she will someday use him, whether he should leave to answer Rose—are really arguments about the risk of being close.

If you trust someone, you hand them the power to ruin you. Both of them have had enough ruin already.

Posey functions as a mirror for this theme too. Her concern that Charlie may need to stop Red someday is loving but also another reminder that intimacy in their world carries safety calculations.

Even Mark’s obsession with Charlie is a distorted version of desire that exposes its worst possibilities: longing that turns into possession, apology that hides violence, fantasy that treats another person as a prize. Against that, Charlie and Red’s fragile closeness becomes more meaningful because it stays uncertain.

Their bond grows when they act in ways that don’t benefit them directly. Red defending Charlie at the bar even when he can’t explain why, Charlie risking Bellamy’s vault to restore Red’s missing piece, Red showing up to save her from Mark, and later using his public power to free her from jail: each moment adds a brick to trust that neither of them can talk into existence.

By the final pages, intimacy doesn’t look like a solved problem. It looks like two people choosing each other despite still being afraid.

The mansion-burning scene is the clearest expression of that choice: they stand together not because everything is safe, but because safety finally feels possible only with the other person beside them.

Moral ambiguity and the struggle for agency

Charlie’s world doesn’t allow clean heroism. She lies, steals, blackmails, bargains with criminals, and sometimes courts violence in ways that would be unforgivable in a simpler story.

But Thief of Night keeps asking what morality means when the structures around you are already corrupt. Charlie’s con-artist instincts are not framed as cute flaws; they are the tools she uses to survive a system that would otherwise chew her up.

Her refusal to go to the hospital, her hiding of pain, her tactical manipulation of guards and Cabals all live in the gray area between self-preservation and harm. The book refuses to punish her for being realistic about power.

Red carries another kind of moral ambiguity. He is capable of brutality and threats, sometimes with a coldness that scares even Charlie.

Yet the narrative keeps showing that his violence is also a response to being hunted, owned, and mislabeled. When he joins Charlie against Mark’s stolen shadows, the decision to free those shadows rather than leave them bound reveals a moral core shaped by empathy for the unfree.

It’s a choice that creates danger—released Blights are not harmless—but it is also a refusal to replicate the same ownership that made Red suffer.

Agency is the heartbeat of this theme. Almost every major plot move is a character fighting to make a choice that isn’t dictated by someone else.

Charlie accepts Mr. Punch’s deal because she wants a narrow path to freedom, but she doesn’t accept his authority over her conscience; she later turns the threat of blackmail back on him.

Red refuses Adeline’s power of attorney not because he understands every legal detail but because he senses what signing would mean: a public return to being somebody’s property. Posey, often sidelined in the action, still asserts agency by securing housing and trying to protect Charlie in the ways she can.

Even minor figures like Rosalva and the quickened shadows show agency when they decide to be freed, to protect Charlie, to stop being extensions of Mark’s ego.

The climax in Solaluna makes the moral landscape explicit. Charlie is blamed for deaths she didn’t cause, threatened for Blights she released to save others, and forced into a new Cabal bargain that still isn’t fair.

Yet she keeps carving out slivers of control in an unfair deal. Red’s public refusal of Adeline after midnight is the same kind of agency on a larger stage: he uses the role forced on him to protect the person who helped him become himself.

Ending with arson isn’t just theatrical rebellion. It’s a moral statement that some systems cannot be reformed from inside, only ended.

The fire is a choice made together, in full knowledge of its consequences. In a story full of coercion, that mutual choice reads as the clearest moral act available.