Things Left Unsaid Summary, Characters and Themes

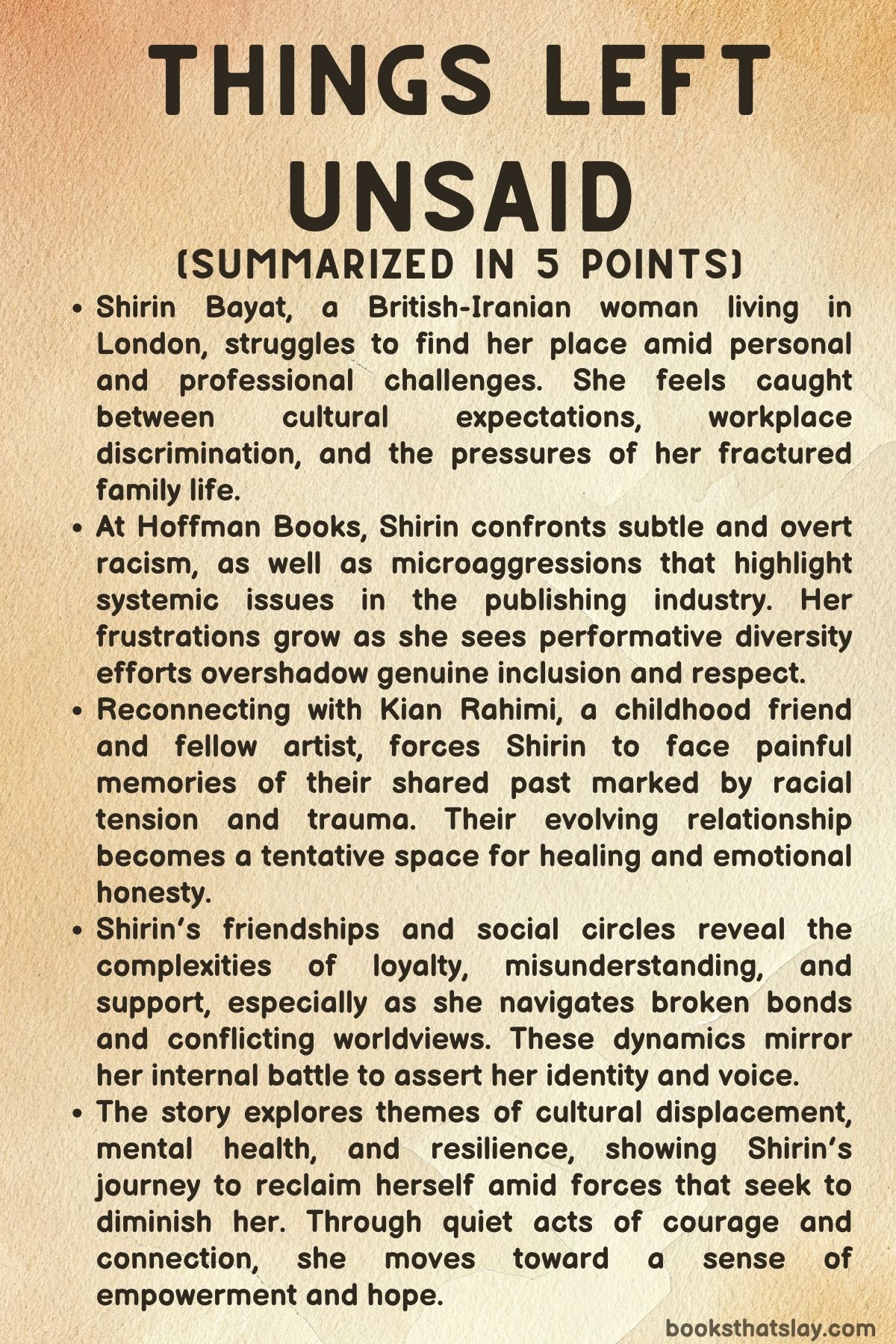

Things Left Unsaid by Sara Jafari is a deeply intimate story about a young British-Iranian woman named Shirin Bayat as she maneuvers through the challenges of adulthood, identity, and the shadows of her past. Set primarily in London, the narrative explores Shirin’s complex relationships—with family, friends, and herself—while confronting issues of racial identity, mental health, and systemic injustice.

The novel paints a candid picture of a woman caught between cultures, careers, and unresolved histories, as she tries to find her voice in a world that often dismisses or misunderstands her. Through moments of reflection, conflict, and tentative hope, the story charts her journey toward self-acceptance and reconciliation.

Summary

The story centers on Shirin Bayat, a 26-year-old assistant editor living in London, grappling with the tensions of personal history and the difficulties of contemporary life. The novel begins at a housewarming party held in a stylishly refurbished Edwardian home in Brixton, a neighborhood Shirin views with ambivalence due to its gentrification and the loss of its original character.

She attends reluctantly with her friend Millie but soon finds herself uncomfortable amid Millie’s social circle, especially because of Millie’s boyfriend Henry, whose controlling and sexist behavior unsettles her. At the party, Shirin unexpectedly reunites with Kian Rahimi, a figure from her youth who unsettles her by stirring up memories of a troubled past they share.

Kian, now an artist pursuing a master’s degree at Goldsmiths, embodies a different path from their school days in Hull, but the tension between them is thick with unspoken history. Kian’s family background adds further layers to his story: his older brother Mehdi, once admired, is now imprisoned, and the family’s experience reflects the cultural displacement and racial challenges of growing up as minorities in a predominantly white environment.

These flashbacks highlight the weight of trauma and societal pressures that continue to shape both Kian and Shirin.

Shirin’s professional life offers no respite. At Hoffman Books, a London publishing house where she works as an assistant editor, she confronts subtle and overt racism, workplace politics, and the superficiality of diversity initiatives.

A notable incident involves an author making a racist remark, which management dismisses, offering Shirin only a symbolic role on a diversity committee without real power or recognition. Shirin’s frustration deepens as the company announces it will publish the memoir of Rob Grayson, a comedian from her hometown whose past bullying and racist behavior deeply wounded her and others.

This decision ignites a sense of betrayal and fuels Shirin’s growing disillusionment with the industry.

The narrative paints a vivid picture of Shirin’s isolation and internal struggle. She shares a cramped London flat with roommates and feels distanced from her childhood friends.

Her relationship with Phoebe, who now has a family, illustrates how differently their lives have unfolded and how difficult it is for Shirin to find genuine support. Battling anxiety and depression, she navigates complex family dynamics, particularly with her father, whose new engagement to a woman Shirin distrusts adds emotional strain.

Her mother is distant, and Shirin often feels caught in the role of caretaker for her emotionally unstable parents despite her own challenges.

Throughout the story, Shirin’s connection with Kian provides moments of comfort and tentative hope. Their conversations reveal mutual struggles with mental health and cultural expectations.

Although their romantic feelings remain tentative and complicated by past trauma, the possibility of renewed friendship and perhaps something more emerges. Their shared history includes painful events—like Kian’s brother’s imprisonment after a racially charged incident—that continue to cast shadows over their lives.

At work, Shirin’s ambitions are repeatedly undercut. A promising project she develops with a bestselling author is appropriated by a colleague, Florence, who receives the credit Shirin deserves.

This betrayal sharpens her awareness of systemic barriers she faces as a woman of color in a competitive, hierarchical environment.

The situation escalates when the company’s CEO announces the publication of Rob Grayson’s memoir, framed as a defense against cancel culture despite his harmful past. In response, Shirin organizes with a group of like-minded colleagues a walkout protest against the decision, risking their jobs to stand for principles of justice and respect.

The protest garners public attention and empowers Shirin to leave Hoffman, cutting ties with a workplace that failed to support her values.

Parallel to this is the depiction of Kian’s life in New York, where he processes his family’s struggles and the emotional burden of his brother’s incarceration. His reconnection with Shirin becomes a source of healing as they share regrets and support each other through their past pain.

Back in London, Shirin’s relationship with other friends remains strained, notably with Phoebe, who fails to acknowledge the seriousness of Shirin’s experiences with racism, leading to a painful falling out.

After resigning, Shirin moves into a new community with supportive friends who help her rediscover aspects of her faith and identity. She also rebuilds her friendship with Hana, recognizing the importance of honesty and setting boundaries in relationships.

The story culminates in a gathering where Shirin and Kian meet again and openly discuss their past fears and future hopes. Though cautious, they express a willingness to explore their relationship anew, signaling a potential path forward.

Throughout the novel, themes of identity, cultural displacement, mental health, systemic injustice, and the search for belonging are explored without sentimentality. Shirin’s journey reflects a quiet but determined resilience as she confronts the realities of racism and marginalization, struggles with family dysfunction, and seeks connection in a fragmented world.

Her evolving relationship with Kian symbolizes both the pain and possibility that come with revisiting the past and moving toward healing.

Ultimately, Things Left Unsaid is a story about navigating the spaces between cultures, histories, and selves, and about the courage required to speak truths that have long been silenced. It offers an honest, nuanced portrayal of a young woman’s attempt to reclaim her narrative and find peace amid the complexities of life.

Characters

Shirin Bayat

Shirin is a complex young British-Iranian woman navigating the challenges of adulthood in London. She works as an assistant editor at Hoffman Books, where she faces workplace discrimination, microaggressions, and systemic racism, which fuel her growing disillusionment with the publishing industry.

Shirin’s internal life is marked by anxiety, depression, and a deep sense of invisibility, complicated further by her strained family relationships—especially with her emotionally unavailable parents and her distrust of her father’s new partner. Raised partly by her grandparents in Tehran, she carries a cultural duality that both grounds and alienates her, contributing to her identity struggles.

Socially, Shirin often feels on the margins, caught between old friendships that no longer serve her and tentative new connections. Her relationship with Kian is central to her story, representing both unresolved past trauma and a fragile hope for healing and intimacy.

Over time, Shirin evolves from a conflicted and silenced figure into someone who finds strength in asserting her truth, challenging injustice, and embracing vulnerability and self-worth.

Kian Rahimi

Kian is a childhood acquaintance and later a close friend and potential romantic interest for Shirin. He is an artist pursuing an MFA in London, whose ethereal impressionist style reflects his emotional depth and personal growth.

Kian’s past is deeply marked by family trauma, including the imprisonment of his older brother Mehdi, which casts a long shadow over his life. This experience, coupled with the racism and social alienation he faced growing up in a predominantly white Northern English town, shapes much of his worldview and art.

Unlike Shirin, Kian appears to have found a channel for healing through his creativity, though he carries guilt and unresolved emotions tied to his family’s struggles. His interactions with Shirin are tender but cautious, filled with unspoken history and shared vulnerabilities.

As they reconnect, Kian offers Shirin both a mirror to her own pain and a possibility of renewed companionship grounded in mutual understanding and empathy.

Hana

Hana is Shirin’s best friend since university, representing a blend of charisma and complexity in Shirin’s social circle. She is engaging and dynamic but sometimes difficult, prone to projecting her insecurities onto those closest to her.

Hana’s presence in the story highlights the intricacies and tensions inherent in adult friendships, where loyalty is tested by emotional needs and misunderstandings. While not a central figure throughout, her interactions with Shirin underscore the themes of connection, boundaries, and the struggles to maintain meaningful relationships amid personal growth and change.

Mehdi Rahimi

Mehdi, Kian’s older brother, is a pivotal figure in Kian’s backstory and the narrative’s exploration of family and trauma. Once charismatic and admired by Kian, Mehdi’s trajectory takes a tragic turn when he is imprisoned following racialized conflicts in their town.

His incarceration symbolizes the harsh realities of systemic racism and social pressures faced by minority families in Britain. Mehdi’s fate deeply impacts Kian’s emotional landscape, influencing his sense of responsibility, guilt, and identity.

Though not present in the current timeline, Mehdi’s shadow looms large over the characters’ lives, illustrating the intergenerational effects of trauma and the challenges of navigating belonging in a hostile environment.

Florence Ainsworth

Florence is Shirin’s privileged colleague at Hoffman Books and serves as a representation of the casual racism and entitlement pervasive in the workplace. Her behavior and attitudes—marked by ignorance and microaggressions—exemplify the barriers Shirin confronts professionally.

Florence’s taking credit for Shirin’s work is a critical moment that exposes the systemic lack of recognition faced by marginalized employees. Through Florence, the story critiques the superficial performativity of diversity efforts and the toxic culture embedded in institutions that claim progress but perpetuate exclusion and inequality.

Phoebe

Phoebe is Shirin’s longtime friend whose life trajectory contrasts sharply with Shirin’s. Stable and socially secure, Phoebe is starting a family with her husband George, embodying a conventional path of adulthood that highlights Shirin’s feelings of isolation and struggle.

Their friendship deteriorates after Phoebe dismisses Shirin’s experiences of racism and trauma, even inviting a known racist into a conversation, which leads to a painful confrontation and eventual estrangement. Phoebe’s role illustrates the painful reality of being misunderstood or invalidated by those closest to us, especially in contexts involving racial and emotional trauma.

Maman Bozorg

Maman Bozorg, Shirin’s grandmother in Tehran, is a crucial emotional anchor throughout the narrative. She represents cultural heritage, unconditional love, and intergenerational wisdom.

Their interactions are moments of warmth, nurturing, and honesty, contrasting sharply with Shirin’s fraught relationships in London. Maman Bozorg encourages Shirin to embrace joy, reject shame, and speak her truth, providing a spiritual and emotional grounding that sustains Shirin through her struggles.

She embodies the themes of family, cultural roots, and the healing power of connection across time and distance.

Rob Grayson

Rob Grayson is a controversial figure in the publishing world and Shirin’s painful past. A comedian from her hometown with a history of bullying and racism, his memoir is controversially championed by Hoffman Books, igniting Shirin’s anger and moral outrage.

Rob’s presence in the story symbolizes systemic injustice and the industry’s complicity in elevating problematic voices while silencing those who suffer. His memoir’s promotion becomes a catalyst for Shirin’s activism and eventual resignation, marking a turning point in her journey toward reclaiming agency and demanding accountability.

Mariam

Mariam is a colleague of Shirin’s who shares her disillusionment with the publishing industry’s failings. She is pragmatic and supportive, encouraging Shirin to reclaim her power and reminding her that they are not bound to toxic environments.

Mariam’s decision to leave Hoffman for a more inclusive workplace underscores themes of resistance and self-preservation. She becomes part of Shirin’s new community, aiding her in reconnecting with her faith and rebuilding her sense of self, embodying solidarity and hope amid adversity.

Dylan

Dylan is Kian’s friend whose family owns the house where the initial party takes place. Though a more peripheral character, Dylan’s family’s support enables Kian’s artistic pursuits and social reentry.

Dylan’s role subtly emphasizes the importance of community and external support in overcoming personal and cultural challenges, as well as the contrasts between privilege and marginalization that weave through the narrative.

Themes

Identity and Cultural Displacement

The narrative explores identity as a multifaceted and often conflicted experience, especially within the context of cultural displacement. Shirin’s British-Iranian background situates her between two worlds, neither of which she fully inhabits without struggle.

Her early childhood in Tehran, raised by her grandparents, provides a foundation steeped in tradition and familial warmth. Yet, growing up in predominantly white Northern England introduces layers of alienation, racism, and the pressure to assimilate.

This cultural liminality manifests in Shirin’s ambivalence about places like Brixton, which is undergoing gentrification—a process she views as erasing the authentic identities of communities, much like how she feels her own cultural identity is compromised or overlooked. This tension shapes her internal conflict as she negotiates belonging both in her heritage and her present life.

The story extends this theme through Kian’s experience, highlighting how racial and social marginalization affect young minorities growing up in environments where they are visibly different and often unwelcome. Their shared experiences underscore how cultural displacement is not merely geographical but deeply psychological, impacting self-worth and relationships.

This theme is underscored by the nuances of Shirin’s relationship with her grandmother, who provides a grounding counterpoint to the disorienting experiences of identity conflict, offering wisdom that encourages acceptance of complexity and imperfection.

Trauma and Mental Health

The persistent shadow of trauma deeply informs Shirin’s emotional world and interactions. Childhood and adolescent experiences of racism, family dysfunction, and social exclusion contribute to ongoing struggles with anxiety, depression, and feelings of invisibility.

The narrative does not treat mental health as a side note but rather integrates it into Shirin’s daily reality—how she manages medication, how workplace microaggressions exacerbate her stress, and how family pressures compound her sense of isolation. Her relationship with Kian also reflects shared trauma, notably in his guilt and grief surrounding his brother’s imprisonment after a racially charged incident.

Both characters carry scars from their past that shape their present selves, informing their hesitancy to fully embrace intimacy or trust. The portrayal of trauma is complex and nuanced, avoiding simplifications; it illustrates how the past continually informs the present, and healing requires confronting unresolved pain rather than ignoring it.

Moreover, Shirin’s mental health challenges are compounded by external invalidation, such as the dismissal she faces at work when raising concerns about racism, which deepens her sense of marginalization. The emotional vulnerability shared between Shirin and Kian in their conversations and art reflects an important aspect of healing: recognition and mutual empathy as a pathway toward reclaiming agency over their lives.

Systemic Racism and Workplace Discrimination

The environment at Hoffman Books embodies the entrenched systemic racism and subtle, often unacknowledged discrimination that pervade ostensibly progressive spaces. Shirin’s experiences with microaggressions, tokenism, and outright dismissiveness from management reveal how diversity initiatives can become performative rather than transformative.

The token role she is given in the Diversity and Inclusion team, alongside blatant racist comments from colleagues and authors, exemplifies the gap between rhetoric and reality within institutional settings. The tension culminates in the controversial decision to publish Rob Grayson’s memoir—a man with a history of bullying and racist behavior—highlighting how profit and reputation often trump ethical considerations in corporate decisions.

The resulting staff walkout organized by Shirin and her colleagues is a significant act of resistance, illustrating how collective action emerges in response to systemic injustice, even when it entails personal and professional risk. This theme expands beyond the publishing house to reflect broader societal patterns where marginalized voices are silenced or sidelined.

The narrative captures the emotional toll this takes on individuals like Shirin, who face the dual burden of navigating workplace hierarchies while carrying the weight of cultural and racial identity.

Friendship, Connection, and Alienation

Interpersonal relationships throughout the story are marked by complexity, reflecting both the human need for connection and the barriers that trauma and difference impose. Shirin’s friendships vary from deeply supportive—such as with Hana and, later, Mariam and Fatma—to strained or fractured, as seen in her deteriorated relationship with Phoebe.

The latter underscores the painful realities of being misunderstood or minimized within friendships, particularly when experiences of racism and trauma are dismissed or trivialized. Shirin’s initial discomfort at social gatherings and her marginal position within various friend groups symbolize her broader feelings of alienation.

Yet, these relationships also offer moments of tenderness and hope. The gradual reawakening of her bond with Kian moves from unresolved tension to cautious intimacy, suggesting that connection can be both healing and fraught with vulnerability.

Their shared history and mutual understanding create a space for empathy, even as both navigate fears rooted in their pasts. This theme shows that human relationships are essential but complicated terrains where identity, trauma, and power dynamics interact, shaping how individuals relate and grow.

Resilience and Self-Reclamation

Despite the pervasive difficulties Shirin faces—cultural dislocation, personal trauma, systemic injustice, and professional betrayal—the narrative is ultimately a testament to resilience and the pursuit of self-reclamation. Shirin’s journey is marked by moments of quiet defiance: standing up to workplace racism, organizing a protest walkout, and choosing to leave toxic environments to seek healthier spaces.

These acts are not grandiose but grounded in a determination to assert her dignity and agency amid structures designed to diminish her. The narrative’s focus on everyday resistance—navigating microaggressions, asserting boundaries in friendships, and confronting painful memories—illuminates the often invisible work marginalized individuals undertake to survive and thrive.

The motif of art, particularly Kian’s painting of Shirin, symbolizes this reclaiming of identity and visibility. By becoming a subject in art, Shirin is both literally and figuratively seen, acknowledged as complex and valuable beyond the constraints imposed by external forces.

The story concludes on a note of hopeful ambiguity, reflecting that resilience is not about erasing pain but learning to live with it, embracing moments of joy and connection while continuing the work of healing and self-discovery.