This Cursed Light Summary, Characters and Themes

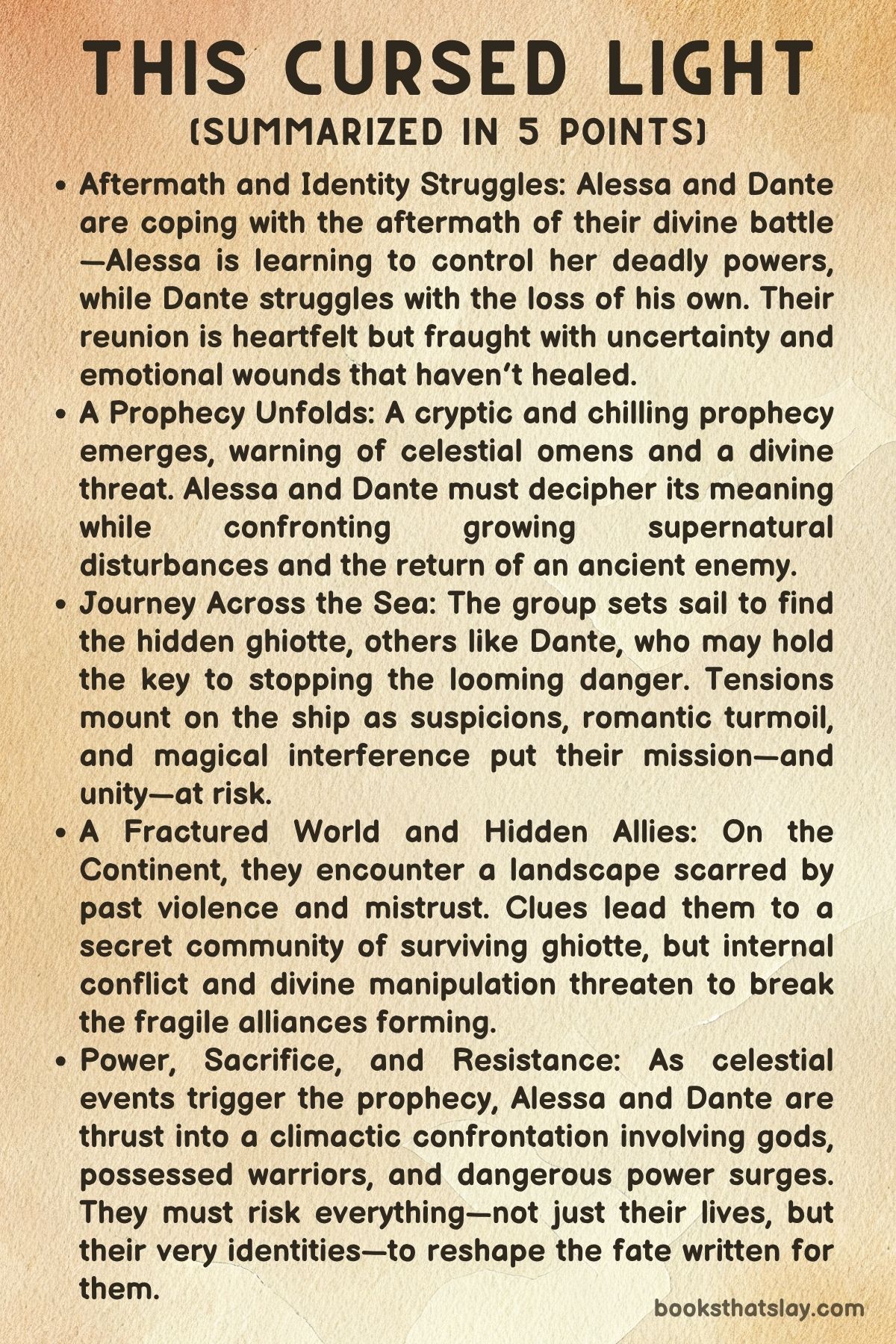

This Cursed Light is the sequel to Emily Thiede’s fantasy debut, This Vicious Grace, and it continues the emotionally charged and high-stakes journey of Alessa and Dante.

Picking up right after the events of the first book, the story follows the pair as they navigate a world still reeling from divine threats, political uncertainties, and fractured alliances. As Alessa embraces her role as Finestra—blessed but burdened—and Dante struggles with the loss of his powers, both are pulled into a new mystery surrounding ancient prophecies, celestial omens, and the scattered remnants of a powerful people known as the ghiotte.

The novel blends romance, prophecy, and rebellion in a richly imagined world where gods meddle and mortals fight to rewrite fate.

Summary

After defeating the divine threat known as the Divorando, Alessa and Dante find themselves in a fragile peace.

Dante, once a healer and protector, now lives without his powers, masking his disorientation through physical labor and isolation.

Alessa, once feared and revered, is now a celebrated Finestra—but her powers remain unstable.

Her fear of harming those she loves continues to haunt her.

Their reunion, though filled with affection, is tinged with guilt, emotional distance, and uncertainty.

During a celebration, a possessed Fonte attacks Dante, and a strange prophecy is uttered, suggesting a new divine disaster.

Despite attempts by leaders to downplay the event, Alessa and Dante suspect a greater danger is on the horizon.

A pattern emerges: whispers, blank-eyed hosts, and celestial omens.

Compelled by the prophecy and the emergence of unnatural forces, the two decide to locate the ghiotte—those with divine gifts like Dante once had.

Joined by companions Kaleb, Adrick, and others, they turn to allies Ciro and Diwata for passage across the sea to the Continent.

The journey is riddled with tension.

Diwata, still recovering from possession, grows increasingly eerie.

The sea voyage triggers memories, dreams, and strange energy surges, heightening the group’s unease.

As they near their destination, the group’s trust begins to unravel.

Arguments break out, and emotional scars resurface.

Alessa’s visions become more vivid and intense, hinting at a larger psychic connection and unseen watchers.

They land on the Continent to find deserted villages and signs of a hasty exodus.

The land feels cursed, and as they venture inland, magical interference and mental manipulation become more frequent.

Clues lead them to a ruined sanctuary once inhabited by the ghiotte.

Alessa experiences a seizure during the blood moon, connecting her with memories of a massacre.

The group is eventually approached by hidden ghiotte survivors who mistrust them—particularly Dante.

A former friend of his, now a zealot, challenges Dante’s motives and authority.

When a solar eclipse darkens the sky, the enemy attacks.

Shadow-beings and divine agents strike hard, reclaiming Diwata and wounding Ciro.

Alessa loses control of her power, and Dante sacrifices himself to stabilize her, momentarily regaining a spark of divinity.

His near-death experience brings him before Dea, the goddess, who offers him a choice.

He returns changed, still himself but now part of something greater.

Together, Alessa and Dante manage to shut the rift that had been opened by Crollo, the antagonist god.

Their combined strength—hers rooted in the power of many, his renewed through sacrifice—halts the divine invasion.

The true meaning of the prophecy reveals itself: not an apocalypse, but a challenge to overcome division and rediscover unity among gods, mortals, and gifted alike.

In the aftermath, the ghiotte survivors begin constructing a new sanctuary.

Alessa proposes an order where Finestras can be trained without the old systems of isolation.

Dante, despite uncertainty, commits to helping lead this new world.

The epilogue finds them months later, living quietly on the edge of the new settlement.

Alessa writes to the next generation, passing down hope and hard-won wisdom.

Though peace has taken root, the final note warns that the gods remain vigilant—watching and waiting.

Characters

Alessa

Alessa begins this sequel as a transformed figure. Once a reclusive Finestra feared for her destructive powers, she is now a publicly admired heroine.

Yet beneath that admiration lies a complex emotional journey. Her powers may be somewhat tamed, but they still act as a barrier to physical intimacy, particularly with Dante, whom she loves deeply.

Alessa’s guilt and longing intertwine, casting a shadow over her desire for normalcy. As the story unfolds, she not only struggles with the physical dangers of her powers but also with prophetic visions and the burden of leadership.

Her arc is one of growing self-assurance. She matures from a reactive survivor into an intentional unifier of people—melding divine gifts, prophecy, and raw human emotion into a force for hope.

By the end, Alessa has not only learned to control her powers but to redefine what it means to be a Finestra. She becomes a bridge between the divine and the mortal, and her legacy begins with her outreach to future Finestras, offering wisdom instead of fear.

Dante

Dante’s evolution in This Cursed Light is grounded in loss, identity, and reinvention. He starts the book deeply shaken—resurrected, but stripped of his healing powers, haunted by who he was and unsure of who he is now.

His emotional and physical restlessness reflects a broader internal void. Renovating a bar and picking street fights are poor substitutes for the divine purpose he once embodied.

His relationship with Alessa is filled with tenderness but underscored by fear. He’s terrified of losing her, of being a burden, of becoming irrelevant.

Throughout the journey, Dante acts as both protector and skeptic. He is deeply suspicious of others yet fiercely loyal.

His transformation reaches its peak when he sacrifices his mortal energy to save Alessa. This leads to a second metamorphosis—this time confronting a divine being and choosing to return changed.

Dante ends the novel as a reluctant leader. Not because he sought power, but because he rediscovered his sense of purpose in service to others and in union with Alessa.

Diwata

Diwata is one of the most tragic and enigmatic secondary characters. First introduced as a visiting Fonte, she becomes a vessel for possession—her free will overtaken, her body used as a warning of future divine conflict.

Though she is later “freed,” her ongoing mutterings and fragmented presence suggest deep psychic scars. Diwata’s possession places her in a liminal space between agency and victimhood.

Her kidnapping in the climax further emphasizes the vulnerability of even powerful figures. Diwata embodies the fragility of autonomy in a world ruled by capricious gods.

Her arc warns of what can happen when divine interference overwhelms mortal strength.

Ciro

Ciro serves as a diplomat and supporter, helping Alessa and Dante embark on their journey to the Continent. Though initially a background figure, his growing involvement highlights the price of loyalty.

He represents the collateral damage of divine conflict—deeply committed, but ultimately a victim of the chaos when he is gravely injured during the final battle.

Ciro’s arc is quieter than others. But he provides essential stability during the group’s turbulent voyage and illustrates how even non-divine characters shape and suffer the outcome of prophecy.

Adrick

Adrick stands out for his emotional intelligence. He often acts as a counterweight to the darker brooding of Dante or the impulsiveness of Kaleb.

Though his trauma is hinted at rather than shown outright, his conversation with Dante about love, guilt, and the need for truth offers one of the emotional keystones of the novel.

Adrick is a voice of reason, compassion, and brutal honesty. His interactions suggest a deep moral compass forged from pain.

His role as a peacekeeper and confidante underlines the importance of emotional support among heroes facing overwhelming odds.

Kaleb

Kaleb is brash, defensive, and combative. These traits often put him at odds with others, particularly Adrick.

His sarcasm masks a fear of failure and powerlessness. While his arc doesn’t receive as much internal exploration as Alessa or Dante, his clashes with Adrick and his struggles with leadership responsibilities show a young man trying to assert control in a situation where none exists.

Kaleb represents the reactive survivor archetype. He is flawed but loyal, and grows in subtle ways through the group’s trials.

Dea

Though Dea’s presence is mostly metaphysical, her influence looms large. The goddess who once chose Alessa offers Dante a second chance during his near-death confrontation.

Her offer—oblivion or transformation—frames the divine not as omnipotent arbiters, but as entities offering flawed choices to mortals.

Dea embodies the theme that gods are not infallible. True power comes from how humans respond to divine tests.

Themes

Power and Identity

One of the central themes in This Cursed Light is the interplay between power and identity, particularly as experienced by Alessa and Dante. The novel interrogates what it means to wield power, lose it, and live in its shadow.

For Dante, the loss of his divine healing powers is not just a physical absence but a deep fracture in his self-conception. His journey is shaped by this vacuum, leading him to question his worth outside of what he once was.

His choice to engage in physical labor—brawling and renovating a bar—is a coping mechanism, a way to assert control in the face of disempowerment. Alessa, on the other hand, undergoes the inverse struggle.

Her powers are intact and even growing, but they are volatile and dangerous, especially to those she loves. Her identity as a Finestra places her on a pedestal, yet it isolates her from intimacy and safety.

Throughout the novel, both characters must redefine themselves beyond their roles as savior or conduit. Their evolution suggests that identity is not fixed by divine favor or magical ability but is formed through vulnerability, moral clarity, and the capacity to adapt.

The final chapters, where Alessa uses her power with controlled confidence and Dante accepts a transformed, semi-divine self, crystallize this theme. The narrative asserts that power, in isolation, does not confer identity; it is the relationship with others and the courage to confront power’s consequences that shapes who we are.

Trauma and Healing

The residue of trauma—personal, relational, and communal—is woven through every major arc in the novel. Dante’s trauma is multilayered: the loss of his abilities, the burden of resurrection, and the emotional weight of past violence and exile.

His inner world is marked by a sense of alienation and inadequacy, even as he appears outwardly composed. Alessa, too, carries trauma—not only from her encounters with divine threats but also from the social rejection and fear that defined her life before she was accepted.

Her dreams, which become increasingly prophetic and disturbing, symbolize a subconscious still grappling with unprocessed fears. The relationship between the two becomes a locus of healing, but not a panacea.

Their intimacy is tested repeatedly by external threats and internal hesitations, especially Alessa’s fear of harming Dante with her uncontrolled energy. What the novel captures astutely is that healing is neither linear nor solitary.

It occurs through confrontation—Dante speaking with his estranged aunt, Alessa reliving the ghiotte massacre through magical seizures—and through communal support, as seen when the ghiotte survivors unite. Importantly, the novel doesn’t treat healing as a return to an unbroken past.

Instead, it frames healing as integration: of memory, identity, and pain. The ending, where both characters are scarred but stable, offers a quiet but powerful resolution.

It shows that survival is not just about escaping trauma but about incorporating it into a new sense of self and community.

Divine Influence and Mortal Defiance

The tension between gods and mortals is a defining thematic current, coloring every major decision the characters make. The gods in This Cursed Light are not omnibenevolent entities but capricious, demanding forces who treat humanity as both tool and pawn.

The divine prophecy that initially looms like an unalterable destiny is later revealed to be more ambiguous—a challenge rather than a command. Alessa and Dante’s evolution is marked by their increasingly critical stance toward divine authority.

Early on, they are reactive, trying to decipher omens and survive the gods’ wrath. But by the final chapters, they begin to question the legitimacy of the gods’ role in human suffering.

Dante’s metaphysical confrontation with Dea is a turning point. He refuses to disappear or submit, even when offered peace, opting instead to return and shape events on his own terms.

Alessa, too, refuses to be merely a divine conduit; she learns to interpret her power not as divine will but as personal agency. The ultimate act of sealing the rift created by Crollo is not a gesture of obedience but one of resistance—of reclaiming cosmic space for mortals.

The novel thus presents a deeply humanistic vision: that divinity does not excuse domination, and that mortals have the right—and perhaps the duty—to question and resist their so-called gods.

The closing epilogue’s line, “The gods are watching. And they are not done,” doesn’t reaffirm divine dominance. Instead, it warns that the struggle for autonomy is ongoing, and vigilance against celestial overreach must continue.

Love, Intimacy, and Trust

The romantic relationship between Alessa and Dante is a core emotional thread, but it is far from a straightforward love story. Their love is under siege—not just by external threats but by the internal fears each harbors.

The novel portrays intimacy as an earned and often painful journey. Physical touch, a common trope of romance, becomes dangerous due to Alessa’s unstable power, adding a literal layer of risk to closeness.

This tension underscores a broader theme: that love, in its most enduring form, is not about passion alone but about mutual trust and emotional transparency. Their moments of vulnerability—Dante confessing his fear of obsolescence, Alessa admitting her nightmares—are more intimate than any physical embrace.

Over time, they learn that protecting each other doesn’t mean withholding truth. It means showing up honestly, even when doing so hurts.

The final kiss that doesn’t burn is not just a romantic payoff; it’s symbolic. It affirms that love must be rooted in balance, not sacrifice, and that control can coexist with surrender.

Their relationship also stands in contrast to the fractured bonds around them—Kaleb and Adrick’s tension, Diwata’s manipulation, the estrangement in Dante’s family—emphasizing that love, to be sustaining, must be continually chosen and re-earned.

In this light, the novel argues that intimacy is not a reward for heroism but a discipline of mutual care and truth.

Prophecy and the Burden of Choice

From the novel’s earliest moments, prophecy exerts an oppressive force over the characters’ lives. The cryptic warning—“What’s white turns red then black”—casts a long shadow, and much of the plot revolves around deciphering its meaning.

But as the story progresses, it becomes evident that the prophecy is not deterministic. Instead, it acts as a mirror, reflecting the characters’ fears and assumptions.

This misreading leads to crucial delays, misunderstandings, and even violence. The journey to interpret the prophecy reveals more about the characters than it does about fate.

Alessa’s visions, which initially feel like uncontrollable omens, eventually become tools of insight once she embraces them not as curses but as part of her expanded consciousness. Dante’s arc similarly shows that prophecy can trap or liberate, depending on how it is understood.

The climax of the novel recontextualizes the prophecy not as a divine mandate for destruction but as an invitation to forge a new path. In choosing to fight, to unite with other ghiotte, and to reinterpret their roles, Alessa and Dante subvert what once seemed inevitable.

The theme ultimately critiques blind faith in destiny and champions agency. Fate exists, but it is mutable—subject to courage, solidarity, and perspective.

By reframing the prophecy as a challenge instead of a sentence, the novel empowers its characters—and its readers—to see choice as the true magic that governs their lives.