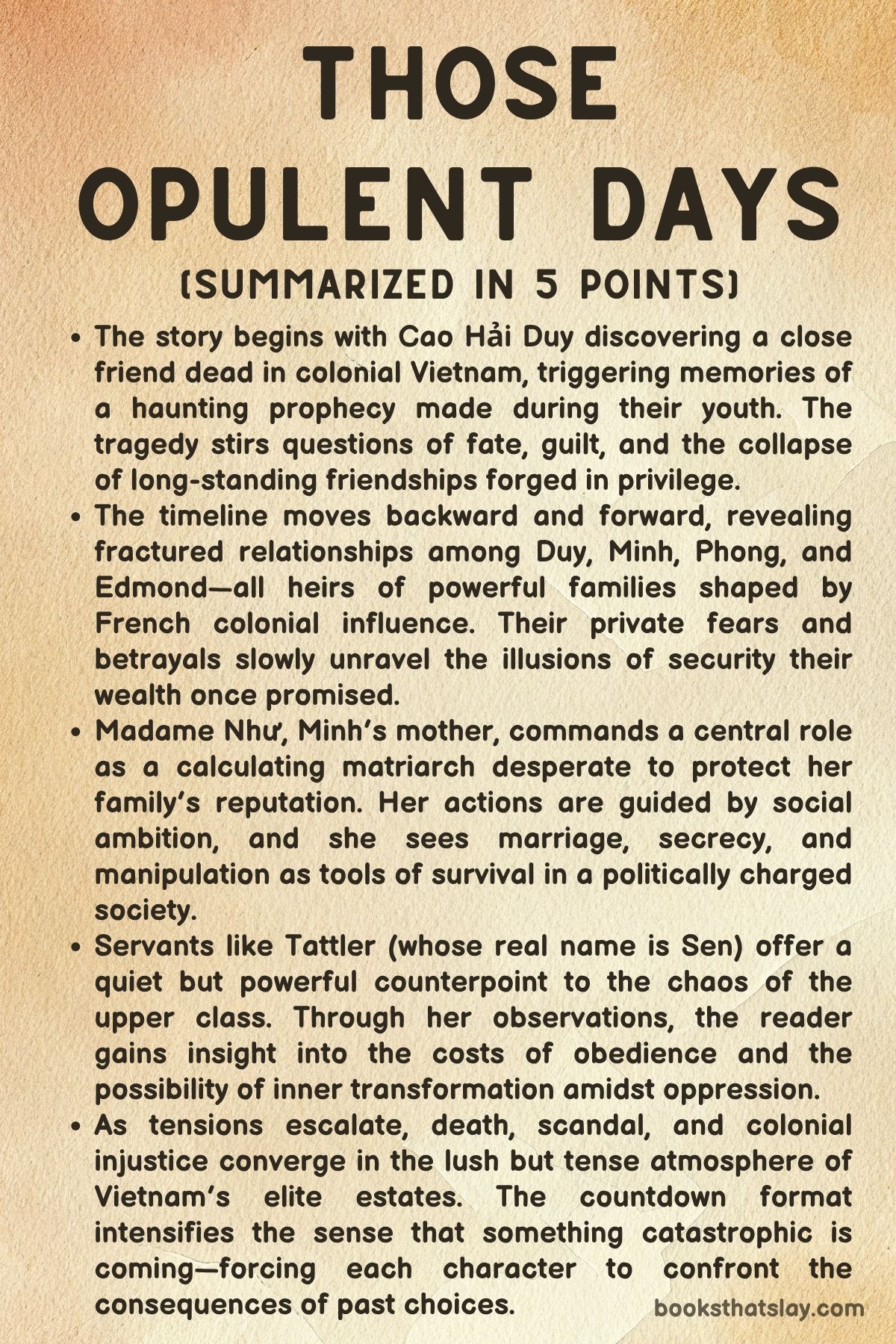

Those Opulent Days Summary, Characters and Themes

Those Opulent Days by Jacquie Pham is a sweeping, emotionally layered historical fiction set in French-occupied Vietnam during the early 20th century. The novel explores the intersections of colonial dominance, class division, and forbidden love through the eyes of a generation marked by inherited privilege and inescapable fate.

With an intricate cast of characters whose lives are scarred by politics, prophecy, and betrayal, the book renders a haunting portrait of identity unraveling under the weight of history. It’s a story about the illusions of friendship, the cruelty of power, and the tragic cost of loyalty to a crumbling world order.

Summary

The story begins in the shadow of death. Duy, one of four childhood friends, reflects on the demise of Phong, a sensitive and withdrawn intellectual who has just died from poisoning.

Thirteen years earlier, the boys had visited a mysterious fortune teller, Master Cần, who prophesied that among them, one would go mad, one would pay, one would agonize, and one would die. That memory returns to Duy with force, triggering deep guilt and sorrow as he tries to make sense of the past.

Phong’s death is not just personal—it feels like the fulfillment of a fate tied to their shared youth and the colonial structure that shaped them.

As the narrative unfolds, each of the four friends is introduced through their own emotional and social struggles. Phong, the first to fall, is marked by profound loneliness and unresolved grief over his mother’s death.

His alienation deepens as he sacrifices a scholarship to remain in Vietnam, only to be slowly consumed by opium and emotional longing. His unspoken love for Edmond, the charismatic half-French member of the group, becomes another source of quiet torment.

Minh, the volatile heir to a rubber empire, grows increasingly paranoid and jealous of Edmond, whose charm threatens Minh’s sense of superiority. Minh yearns for attention and control, but his violent outbursts alienate those closest to him.

His relationship with Hai, a servant girl, offers moments of tenderness but is poisoned by possessiveness and status imbalance. Minh’s love is not liberation for Hai—it’s a form of domination she tolerates but never truly embraces.

Hai’s life is shaped by exploitation. Sold by her mother into service under Madame Như, Minh’s mother, Hai is renamed “Tattler” and robbed of her identity.

She becomes both a pawn and a witness in a household structured by cruelty and hierarchy. Her secret relationship with Minh complicates her dreams of freedom, especially as Madame Như’s schemes entangle her further in a web of betrayal.

Madame Như ultimately orchestrates Hai’s abduction, delivering her into the hands of Monsieur Leon Moutet, a brutal colonial patriarch. Hai’s final act, exposing Edmond’s queerness to protect herself, leads to her death but also detonates a chain of political and emotional consequences.

The narrative then explores the psychological descent of Edmond, who is deeply scarred by childhood trauma and shame. Raised by Adeline, a French woman whose racism is veiled by politeness, and shadowed by Marianne, a caretaker torn between duty and compassion, Edmond becomes cruel and self-destructive.

His assault on Hai mirrors his internal turmoil and his inability to reconcile with his sexuality. A hallucinated confrontation with Phong brings him to the edge of breakdown, leading to a suicide that appears voluntary but is later revealed to be a carefully orchestrated act of revenge.

Sen—formerly Hai’s fellow maid—emerges as the silent agent of retribution. Her years of subjugation and observation culminate in a single act of defiance: poisoning Edmond.

In doing so, she tears down the illusion that power and class protect from consequence. Her revenge is not only personal but symbolic, a challenge to the system that has enabled so much suffering.

As Edmond’s death shocks the colonial elite, his father Leon lashes out. He leverages his influence to accuse Phong of disgracing the family name, using his suspected relationship with Edmond as justification.

Minh, now a man lost to rage and madness, supports the accusation. Duy remains paralyzed by fear, and Phong is left defenseless.

The once-inseparable friends are now fractured by betrayal and cowardice. Phong is arrested, beaten, and executed.

His death becomes a harrowing symbol of sacrifice and love, a final assertion of dignity in a world that denied him both.

The story shifts again to trace a failed rebellion on Minh’s rubber plantation. When workers rise up against exploitation, Minh responds with ruthless violence.

He interrogates the captured rebels, among them Tư, the disowned stepbrother of Phong. Tư’s demands for basic rights are met with scorn and bullets.

The executions mark a decisive break between the friends and any lingering conscience Minh possessed. His transformation into a tyrant is now complete, his actions mirroring the very colonial forces he once sought to emulate.

As the dust settles, the survivors carry their own burdens of grief and complicity. Marianne attempts redemption by offering Sen a chance to escape, but Sen chooses anonymity over rescue, her defiance intact.

Minh descends into madness, haunted by hallucinations and loss. Duy retreats from the world entirely, entering a monastery to live in silence and remembrance.

He buries Edmond’s locket beneath a frangipani tree, a small gesture of mourning for friends who died by betrayal, violence, and unfulfilled love.

Madame Như, who began the story praying at her family altar, ends as a diminished figure, her schemes having cost her everything. Her desire to preserve family honor at all costs not only destroyed her son’s chance at happiness but triggered a chain of events that shattered the lives of everyone in her orbit.

Those Opulent Days closes not with redemption but with elegy. The legacy of colonialism, familial cruelty, and social hierarchy leaves no one untouched.

Friendship crumbles under pressure, love becomes a casualty of control, and identity is lost amid the constant performance demanded by power. The novel offers no heroes—only survivors shaped by silence, fear, and memory.

What remains is the question of what it means to endure when history, destiny, and betrayal have already made their mark.

Characters

Duy

Duy is the emotional and psychological nucleus of Those Opulent Days, a man suspended between memory, guilt, and a prophetic curse that continually warps his understanding of the past and present. He is introduced in the wake of Phong’s death, reeling from a deep sense of powerlessness that stems from his inability to prevent the fates foretold by Master Cần.

Duy’s intelligence is matched by a cold rationality, often hidden beneath a façade of politeness and strategic maneuvering. He is a symbol of the upper-class Vietnamese elite, navigating colonial privilege while internally eroding from moral contradictions.

His descent into grief and reflection is not just for his fallen friend but for a version of himself he abandoned long ago, when he chose loyalty to the colonial order over emotional truth. Over time, Duy becomes increasingly detached from the political and social theatre of his class, culminating in his transformation into a monk.

His life of penance, marked by quiet rituals and symbolic burial of the past, shows a man irrevocably changed—no longer capable of reconciling the horror of his complicity with the privileges he once wielded.

Phong

Phong is perhaps the most tragic figure in Those Opulent Days, a gentle soul crippled by unfulfilled desires and emotional repression. His pain is twofold: the alienation from his emotionally vacant father and the silent ache of his forbidden love for Edmond.

Phong’s identity as an educated, cultured man is never fully recognized in a society divided by race, class, and colonial hierarchy. His abandonment of a scholarship abroad to remain in a homeland that rejects him mirrors his refusal to let go of Edmond, even when it becomes clear their relationship is doomed.

Phong’s dependency on opium is less a personal vice than a means of emotional escape, a numbing balm for his grief and unspoken love. His death, orchestrated through colonial power and sanctioned betrayal, becomes a symbolic act of martyrdom.

In his final moments, Phong embodies the cost of gentleness in a brutal world, a man destroyed not by weakness but by a society unwilling to grant him the space to exist fully.

Minh

Minh is a study in self-destruction, a man raised in the lap of colonial excess but consumed by feelings of inadequacy and jealousy. The heir to a vast rubber empire, Minh’s psychological landscape is dominated by his inferiority complex—particularly in relation to Edmond, whose charm and biracial heritage ignite Minh’s deep insecurities.

Minh’s longing to be central to his circle of friends devolves into possessiveness, especially in his relationship with Hai. What begins as fragile affection turns into violent control as Minh seeks to assert dominance over the only person who seems to love him unconditionally.

His failure to understand the difference between love and ownership is further compounded by his descent into madness, especially after Hai’s disappearance. His brutal crackdown on the plantation rebellion, and the execution of Tư, mark his complete moral breakdown.

In the end, Minh is a man who loses everything—not only his friends and sanity but his capacity for redemption.

Hai

Hai represents the clearest victim of the novel’s entrenched classism and patriarchy. Born into poverty and later renamed “Tattler” upon her entry into servitude, Hai’s life is marked by the systematic stripping of her identity and agency.

Her relationship with Minh provides fleeting warmth, but is ultimately defined by imbalance and fear. Despite her emotional depth and quiet resilience, Hai is consistently betrayed by those in power, culminating in her drugged abduction and brutal rape at the hands of Leon Moutet.

Her final act—revealing Edmond’s secret in an attempt to destabilize her captors—exemplifies her refusal to remain voiceless. Though it costs her life, this moment of resistance shatters the illusion of class harmony and underscores the narrative’s insistence that even the most oppressed can strike a fatal blow against the system that imprisons them.

Edmond

Edmond is a deeply tormented figure in Those Opulent Days, embodying the contradictions of colonial legacy and repressed identity. Born of a French aristocrat and raised under the watch of women both cruel and well-meaning, Edmond exists in a liminal space between privilege and suffering.

His queerness, hidden beneath layers of social expectation and internalized shame, fuels his descent into alcoholism and cruelty. The trauma of childhood abuse, combined with his inability to forge authentic emotional connections, makes Edmond both a victim and a perpetrator.

His brutality, particularly toward Tattler, is an attempt to reassert control in a world where he feels perpetually disempowered. His hallucinations, especially of Phong’s voice, reveal a fractured psyche teetering on the edge of collapse.

Edmond’s eventual death by poisoning—engineered by Sen—acts as both a tragic end and a necessary reckoning, laying bare the toxic consequences of silence, repression, and unchecked privilege.

Madame Như

Madame Như is a character of chilling control, the matriarch of a fading dynasty who sacrifices morality for the preservation of social status. Her outward devotion to tradition and ritual masks a ruthless will to dominate, especially over those she deems beneath her.

By orchestrating Hai’s abduction and covering it up through lies and gaslighting, Madame Như emerges as a figure willing to destroy lives to maintain appearances. She views love as a dangerous deviation and treats her son Minh’s vulnerabilities as weaknesses to be corrected, not healed.

Her complicity in colonial violence, particularly in aligning with Monsieur Moutet, exposes how native elites internalized and perpetuated the very systems that oppressed them. By the end of the narrative, she is a woman hollowed out by her own betrayals, worshipping at an altar that reflects not grace, but decay.

Sen (Tattler)

Sen, formerly known only by her nickname Tattler, evolves from a passive observer to the story’s quiet revolutionary. Forced into servitude and silence, she spends much of the novel absorbing the injustices around her, storing secrets like currency.

Her cynicism and sharp awareness distinguish her from other domestic workers—Sen understands power and how it flows, when to avoid it and when to weaponize it. Her decision to poison Edmond is not only an act of vengeance for Hai but a calculated strike against a system that believed her incapable of resistance.

Her escape into anonymity after the murder is emblematic of her survivalist instinct, but also of the erasure that defines lower-class lives. Sen’s arc challenges the idea that the powerless are voiceless, proving that the most potent acts of defiance often go unnoticed.

Marianne

Marianne is a tragic bystander in Those Opulent Days, a woman who recognizes cruelty but lacks the courage or clarity to stop it. As Edmond’s caretaker, she sees his deterioration and tries, with limited means, to intervene.

Her sympathy for Hai and later for Tattler speaks to her latent moral awareness, but she is ultimately paralyzed by fear and societal pressure. Marianne’s failure to act becomes a powerful indictment of passive complicity—the harm done not through malevolence, but through silence and retreat.

Her return at the novel’s end to witness Duy’s quiet rituals reflects a final attempt at reckoning. In mourning Edmond and Hai, she also mourns her own failures, seeking some semblance of peace in a world that never offered easy absolution.

Pierre

Though a peripheral figure, Pierre is crucial in establishing the story’s colonial power dynamics. A once-proud French soldier, Pierre finds himself reduced to a pawn in the decadent world of native elites.

His arrival at the mansion of Cao Hải Hà, and his humiliating encounter with Duy, symbolizes the inversion of colonial authority—an uncomfortable reminder that control can be circumstantial and fleeting. Pierre’s internalized superiority is eroded by the realization that his supposed dominance means little in the face of wealth and native power.

His disillusionment mirrors the slow unraveling of the colonial myth, positioning him as a relic of a crumbling empire, defeated not by violence but by irrelevance.

Leon Moutet

Leon is the monstrous embodiment of colonial patriarchy in Those Opulent Days. Arrogant, calculating, and sadistic, he sees Vietnam as his playground and its people as disposable.

His control over figures like Madame Như and his brutal abuse of Hai illustrate his unchecked power. Yet, Leon’s authority is also fragile—deeply invested in maintaining a façade of purity and lineage.

Hai’s revelation of Edmond’s queerness strikes at the heart of his ego, revealing the fragility beneath his tyranny. His reaction—to orchestrate Phong’s execution—shows the extent to which colonialism weaponizes shame and masculinity.

Leon is not merely a villain; he is the architect of destruction, proof of how colonial systems breed monsters under the guise of order.

Themes

Colonial Power and Class Oppression

In Those Opulent Days, colonial power is not merely an abstract historical context but a living, breathing force that defines every relationship, every gesture, and every tragedy. The French colonial structure, particularly as it manifests in Saigon and Đà Lạt, establishes a hierarchy in which native Vietnamese characters are continuously subjected to humiliation, violence, and moral compromise.

This hierarchy is not only external—enforced through physical power and economic structures—but internalized by its victims, many of whom adopt the very logics that oppress them. Characters like Pierre believe themselves to be superior to the Vietnamese, yet quickly find themselves subjugated when faced with native wealth and sophistication, as seen in Duy’s effortless authority within the mansion.

The power dynamic is flipped, suggesting that class and money—not just race—govern influence in this fractured society. Minh’s rubber empire and Madame Như’s status grant them dominion not only over their Vietnamese peers but also over French soldiers, showcasing how wealth in a colonial system can blur conventional racial hierarchies while reinforcing oppression.

Servants like Hai and Tattler are born into this cruel system, robbed of their names and choices, their value determined solely by how well they serve. Their fates highlight how deeply classism and colonialism intersect to dehumanize and control, leaving behind scars that are emotional, physical, and generational.

Gender, Violence, and Sexual Control

Gender in Those Opulent Days is inseparable from violence and control. Women in this world exist under constant surveillance and exploitation, their bodies commodified and their choices either stolen or shaped by the expectations of men.

Hai’s tragic trajectory—sold as a child, renamed Tattler, raped and killed—exemplifies how femininity is rendered powerless in a male-dominated and colonially structured world. Her death is not only an individual act of brutality but a symbolic silencing of female autonomy.

Madame Như, on the other hand, manipulates the system to maintain her position but ultimately perpetuates the same violence she once sought to avoid. She gaslights Minh and delivers Hai to a colonial predator, using her maternal status to mask her cruelty.

Even Marianne, though more sympathetic, remains complicit through her silence and failed attempts at redemption. The narrative shows how women, regardless of their status, must navigate systems that commodify their identities.

For male characters like Minh and Edmond, gender becomes another axis of domination—Minh’s possessiveness turns into violent outbursts, while Edmond’s internalized shame around his queerness metastasizes into sadistic behavior. The story reveals that gender-based violence is not limited to physical acts but also manifests in silencing, emotional manipulation, and denial of identity.

Friendship and Betrayal

The friendship between Duy, Minh, Phong, and Edmond is portrayed not as a sanctuary but as a crucible of latent rivalries, unspoken desires, and looming betrayal. What begins as a childhood bond rooted in shared privilege disintegrates under the pressures of class difference, suppressed love, and the burdens of prophecy.

The ominous forecast from Master Cần—that one will die, one will pay, one will agonize, and one will lose his mind—becomes the defining structure of their collective fate. Each friend embodies a specific facet of downfall, their closeness only amplifying the eventual betrayals.

Minh’s envy and romantic jealousy drive him to violent extremes, including his massacre of rebels and mistreatment of Hai. Phong’s hidden love for Edmond isolates him, and his loyalty ends in martyrdom.

Edmond’s detachment and arrogance mask deep emotional fractures, which in turn provoke resentment and invite retaliation. Duy, desperate for control and moral clarity, fails to intervene in time, making him complicit by omission.

The prophecy’s fulfillment is not mystical but psychological—it reflects how betrayal often stems from our deepest fears and insecurities. The narrative transforms friendship into a battlefield, where affection is inseparable from power and every act of love risks becoming a prelude to treachery.

Fate, Prophecy, and Inescapable Destiny

In Those Opulent Days, fate is not just suggested through prophecy but confirmed through the painful unfolding of lives shaped by both personal choices and historical inevitability. The prediction by Master Cần, far from being a narrative gimmick, becomes a lens through which every character’s action is scrutinized and haunted.

It imposes a structure of fatalism on the narrative, where every moment seems to be marching toward a predetermined collapse. Duy’s descent into spiritual penance, Minh’s mental unraveling, Phong’s tragic execution, and Edmond’s death all align with the chilling vision delivered in childhood.

Yet the novel suggests that fate is not imposed by supernatural forces alone—it is also constructed by systemic violence, colonial history, and entrenched social roles. These elements limit free will, making the prophecy feel more like a sociopolitical blueprint than a mystical forecast.

The power of prophecy lies in its capacity to shape belief. Once internalized, it dictates behavior, fosters paranoia, and justifies inaction.

Duy, for instance, becomes obsessed with identifying which of them will fulfill each part of the prophecy, ultimately missing the opportunity to prevent it. The narrative critiques not fate itself, but the human inclination to surrender to it, using it as an excuse for moral paralysis.

Repression, Identity, and Psychological Collapse

Throughout the narrative, the characters struggle with personal identity in a society where appearances are mandated and inner desires are dangerous. Edmond’s crisis is the most visible manifestation—his queerness, suppressed and shamed by his colonial French upbringing, becomes the source of both self-harm and cruelty to others.

He lashes out as a way to distance himself from the vulnerability he is too ashamed to embrace. Similarly, Minh’s fragile masculinity and inability to process loss lead him to violence and madness.

The story shows that when identity must be hidden or denied, it metastasizes into emotional and psychological disintegration. Phong’s silence about his feelings for Edmond, coupled with his father’s rejection and his failure to claim a life beyond colonial expectations, leads to addiction and despair.

Even characters like Sen, who remain in the background, suffer from the long-term erosion of self—her revenge is a final grasp at reclaiming identity stolen by servitude and abuse. Repression in this novel is not only about sexuality or gender, but also about class, race, and grief.

The internalization of shame, fear, and societal expectation eventually corrodes the minds of even the most resilient characters, making madness and death seem like the only logical outcomes.

Resistance, Revenge, and the Illusion of Justice

Amid the bleakness, Those Opulent Days contains pockets of resistance—some loud, some quiet, but all costly. Tư’s defiance during his execution, Sen’s poisoning of Edmond, and Hai’s final act of truth-telling all serve as symbolic assertions of agency.

These acts do not dismantle the system, but they pierce its veneer of invincibility. They represent moments where the oppressed briefly reclaim narrative control, even if the consequences are fatal.

The story complicates the notion of justice by showing how revenge can be both righteous and tragic. Sen’s revenge is meticulously planned and executed, but it does not restore her freedom or bring closure.

Tư’s protest highlights the moral bankruptcy of the elite but is quickly buried—literally and metaphorically—by those in power. Justice in this world is not determined by right or wrong but by hierarchy, loyalty, and silence.

Even Phong’s death, noble in sacrifice, is a strategic move by Leon to reassert colonial dominance. The survivors—Duy in solitude, Marianne in guilt, Sen in obscurity—are not victors but remnants, carrying the weight of vengeance that changed nothing and yet meant everything.

These actions are not triumphant resolutions but mournful testaments to the human need to strike back, even when justice is unattainable.