Three Bags Full Summary, Characters and Themes

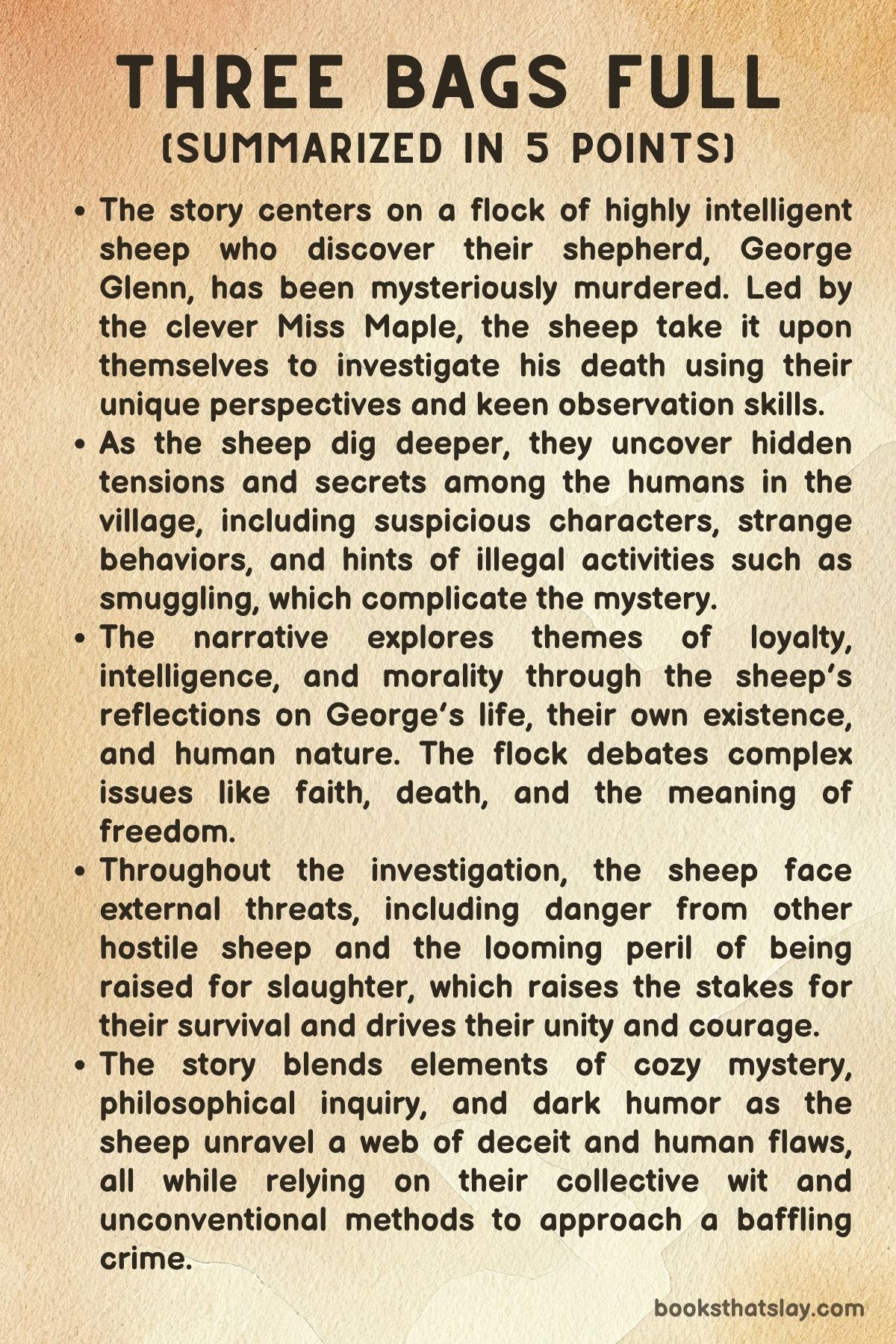

Three Bags Full by Leonie Swann is a quirky and darkly humorous mystery novel set in a small village where a flock of sheep embarks on an investigation into the untimely death of their shepherd, George Glenn. The sheep, led by the sharp and observant Miss Maple, quickly deduce that George’s death was no accident and, unable to directly communicate with humans, they must solve the case themselves.

As the flock uncovers more details surrounding George’s life and his possible enemies, they uncover a complex human drama that blurs the lines between justice, morality, and the limits of animal understanding.

Summary

The story begins with the death of George Glenn, the shepherd of a flock of sheep in the village of Glennkill. George is found impaled by a spade in the meadow, and his body lies in the open for all to see.

His sheep, initially bewildered and frightened by his sudden death, quickly begin to realize that something isn’t right. The cleverest of them, Miss Maple, immediately suspects foul play, believing that a human, not an animal, is responsible for his death.

As the sheep reflect on their experiences with George, they recall his many flaws—his unkindness, his strange behavior, and his moments of cruelty—yet they still feel the need to find out what truly happened to him.

The flock begins their investigation by observing the humans around them. They notice odd reactions from various individuals in the village, particularly George’s wife, Kate, and a man known as the butcher, who seems to have an unsettling presence.

As the sheep continue to gather clues, they uncover inconsistencies in the humans’ stories and actions. They also notice that there’s more to George’s death than a simple murder, with multiple suspects emerging from his complex relationships.

The sheep begin to suspect that George’s death might be connected to deeper issues, including financial matters, personal grievances, and hidden secrets.

One significant clue comes in the form of a single hoofprint found on George’s stomach, leading the sheep to question whether one of them might have had something to do with his death. Despite their initial shock at this possibility, the sheep press on with their investigation, focusing on the most likely suspects in George’s life.

They turn their attention to God, a mysterious and tense character who had a history of conflict with George. Their suspicions grow as they piece together more details, including a strange series of events involving George’s will, a missing object, and a human named Heather who might hold crucial information.

As Miss Maple leads the flock through their investigation, the sheep’s curiosity and determination grow. They begin to realize that their dependence on George, both for survival and for the care he provided, made them complicit in a way.

The flock wrestles with their guilt over their occasional raids on George’s vegetable garden during his absence, but they also remain determined to seek justice for their fallen shepherd. This internal conflict adds layers of complexity to the sheep’s investigation, as they weigh their own feelings of loss and betrayal against their desire to uncover the truth.

The investigation leads the sheep to discover more about the mysterious world of humans and the tensions that exist within it. As they watch humans interact, they begin to see the deeper complexities of their relationships with one another.

The sheep slowly realize that the world beyond their meadow is far more dangerous and complicated than they had ever imagined. At the same time, they are becoming more aware of their own vulnerabilities and the potential threats that humans might pose to their existence.

Despite their efforts, the sheep find it difficult to make sense of the many conflicting emotions surrounding George’s death. They uncover more and more about the humans’ private lives, but they struggle to understand the complex motives that led to George’s death.

The suspicion that one of their own could have been involved in the death weighs heavily on them, but they refuse to give up on their search for justice.

The narrative takes a darker turn when the sheep discover that George’s death might not have been a straightforward murder at all. They begin to consider the possibility that George might have taken his own life, leading to a reevaluation of everything they thought they knew about the situation.

This realization complicates their sense of justice, as they now have to grapple with the idea that the death might not have been an intentional act of violence, but rather the result of George’s own inner turmoil and struggles.

As the mystery unfolds, the sheep face many challenges. Their investigation is frequently hindered by misunderstandings and the limitations of their own perceptions.

The humans around them remain largely unaware of the sheep’s suspicions, making it difficult for the flock to gain any meaningful traction in their quest for answers. Despite these setbacks, Miss Maple’s determination to uncover the truth never wavers, and she continues to lead the flock on their path to justice.

In the end, the mystery of George’s death remains unresolved, leaving the sheep to confront the complexities of their own lives and the world around them. The flock’s search for justice has taken them to unexpected places, forcing them to question their understanding of what is right and wrong, and what it means to be truly free.

As they reflect on the mystery of George’s death, the sheep begin to realize that, while they may never fully understand the intricacies of human emotions and motives, they have gained a deeper appreciation for the world they inhabit and their place within it.

The novel concludes with the sheep returning to their simple lives in Glennkill, although their experiences have forever altered their perceptions of the world. The events surrounding George’s death may never be fully explained, but the sheep are left with the knowledge that, in their search for justice, they have discovered much about themselves and the world they share with the humans around them.

The mystery of George’s death may have eluded them, but their journey toward understanding has only just begun.

Characters

Miss Maple

Miss Maple is the central figure in Three Bags Full and the one who steers the flock through the complex investigation into George Glenn’s death. As the cleverest sheep, she exhibits traits of sharp intelligence, curiosity, and leadership.

Her determination to uncover the truth about George’s death drives much of the narrative. While the flock is initially rattled by George’s sudden demise, Miss Maple quickly takes charge, guiding them to look beyond the obvious and delve deeper into the potential human involvement in his death.

She is not just a leader but also a symbol of the sheep’s capacity for logical thinking and reasoning in a world they do not fully understand. As the story progresses, Miss Maple’s dedication to seeking justice for George becomes a moral anchor for the group.

Her ability to see beyond the surface, think critically, and remain resolute despite the risks sets her apart from the other sheep, who tend to be more concerned with their daily routines and safety.

Othello

Othello, the black sheep, plays a crucial role in the investigation, bringing an additional layer of perspective to the flock’s quest for justice. His role is often one of support to Miss Maple, offering insights into the unfolding mystery, although his more emotional and instinctual reactions sometimes place him at odds with her more logical approach.

Othello’s identity as the “black sheep” of the flock hints at a deeper narrative of isolation and difference. While Miss Maple represents intellect and leadership, Othello’s character is grounded in the more visceral aspects of the sheep’s existence, reflecting the struggles of being marginalized or misunderstood.

His attachment to the investigation is influenced by his desire to understand his place within the flock, as well as to protect the group from the dangers lurking in their human surroundings. Othello’s character arc is less about finding answers than it is about coming to terms with the complexity of life and death within the context of the flock’s existence.

Ritchfield

Ritchfield, Melmoth’s twin brother, is a character that embodies the tension between individuality and the pressures of societal expectations. His contrasting dynamic with Melmoth reflects a deeper philosophical divide.

While Melmoth seeks personal defiance and independence, Ritchfield is more concerned with maintaining order and safety within the flock. This dichotomy speaks to broader themes of conformity and rebellion, and Ritchfield’s struggles with Melmoth’s defiance serve as a constant source of conflict in the narrative.

Ritchfield’s character is defined by his sense of responsibility toward the flock and his more conventional views about life, death, and the rules that govern their world. He is concerned with protecting the group from external threats, such as the butcher, but also grapples with the fear of what might happen if the sheep stray too far from the norms of their community.

Zora

Zora is a more distant and philosophical character who often appears detached from the emotional intensity surrounding George’s death and the subsequent investigation. Her reactions to the events unfolding in Glennkill are less about finding justice for George and more about contemplating the nature of existence and the meaning of their lives.

Zora’s contemplative nature contrasts sharply with Miss Maple’s focused determination and Othello’s emotional reactions. She represents the more existential side of the flock, one that questions the value of action and whether it is worth pursuing answers in a world that might not have any simple explanations.

Zora’s character serves as a reminder that the sheep, like humans, wrestle with questions of purpose and identity, and her role in the story underscores the complexity of their internal lives.

Melmoth

Melmoth is a wandering sheep whose journey represents themes of self-discovery, survival, and existential questioning. Unlike the other sheep, Melmoth is driven by a desire to prove himself and challenge the expectations placed upon him by his flock and family.

His flight from the butcher and subsequent quest to spend five nights alone in the wild is a pivotal moment in his character development. Throughout his journey, Melmoth grapples with his fears, loneliness, and the harsh realities of the world outside the safety of the flock.

His defiance initially appears as a youthful act of rebellion, but it gradually transforms into a deeper reflection on the meaning of freedom, mortality, and the nature of belonging. Melmoth’s encounter with a human leg bone and the discovery of a human body force him to confront the existential tension between individuality and community.

By the end of his journey, Melmoth has shifted from a rebellious figure to one who has gained a more profound understanding of life’s fragility, symbolizing personal growth and introspection.

Maude

Maude is a character that represents the more cautious and survival-oriented mindset within the flock. She is concerned with the safety and well-being of the group, often prioritizing these above the pursuit of justice or answers.

While Miss Maple leads the charge for investigation, Maude’s focus is on the practical aspects of the situation—what needs to be done to ensure the flock’s security. Her character embodies the instinct to preserve the status quo and protect what is familiar, even if it means ignoring or avoiding the unsettling truths that Miss Maple seeks to uncover.

This creates a tension within the flock, as Maude’s desire for stability conflicts with the more adventurous and inquisitive nature of characters like Miss Maple and Melmoth. Maude’s perspective is crucial in understanding the broader theme of fear and how it shapes the behavior of individuals in times of crisis.

Beth

Beth’s role in Three Bags Full is central to the mystery surrounding George’s death, and her character is marked by ambiguity and internal conflict. She is initially suspected by the sheep of being involved in George’s death, and their suspicions are heightened by her strange relationship with him.

Throughout the narrative, Beth grapples with guilt, love, and her role in George’s life, leading to an eventual revelation that complicates the flock’s perception of justice. Her emotional conflict adds depth to the narrative, as it reveals the complexities of human relationships that are beyond the sheep’s full understanding.

Beth’s character arc speaks to the themes of remorse and moral ambiguity, with her actions and motivations being open to interpretation. In the end, Beth’s internal struggle provides a crucial counterpoint to the sheep’s search for justice, suggesting that the truth is not always as clear-cut as they would like it to be.

Themes

Justice and the Search for Truth

The quest for justice is at the heart of the narrative, as the sheep of Three Bags Full strive to understand the circumstances surrounding their shepherd George’s death. The investigation led by Miss Maple is rooted in a profound sense of responsibility, not only to George but to themselves and their place in the world.

Their investigation begins with the assumption that someone must be held accountable for the unnatural death, a murder they suspect may have been committed by one of the humans they depend on for survival. Their search for truth is complicated by their inability to directly communicate with the humans, leading them to devise creative, often theatrical methods to communicate their suspicions.

The dramatic scene at the Mad Boar pub, where they attempt to perform their suspicions through a series of tricks and gestures, illustrates the sheep’s unwavering desire to achieve justice. Despite the misunderstandings that arise from their attempts, the sheep are undeterred in their search for answers.

Their perseverance symbolizes a broader theme of the difficulty in achieving justice in an often indifferent world. The concept of justice here is not just about retribution but also about understanding the complexity of human emotions and actions, as the sheep begin to question whether George’s death was truly a murder or possibly a suicide.

This ambiguity challenges their initial assumption and complicates their pursuit of justice, highlighting the elusive nature of truth and the consequences of their ignorance.

Memory, Identity, and the Complexity of Human Emotions

The theme of memory and identity emerges as the sheep grapple with their understanding of their relationship with George and the larger human world. Their collective memory of George is a mixture of admiration for his eccentricities and disdain for his harshness, creating a complex portrait of the shepherd they once relied on.

This reflects the sheep’s struggle to reconcile their personal experiences with a broader, more complex view of George’s life and death. As they continue their investigation, the sheep begin to confront their own memories of George, as well as the guilt they feel for having benefited from his absence, particularly when they raided his vegetable garden.

The emotional journey the sheep undergo is one of self-reflection, as they come to terms with their own role in the world and their place within the larger human drama. Their evolving understanding of George’s death forces them to question their identities as animals dependent on humans, forcing them to recognize their own vulnerability in a world controlled by human complexities.

The theme extends beyond memory and identity to include the sheep’s struggle to comprehend the full range of human emotions that might have driven George’s actions, from love to betrayal, and to understand how these emotions shape their reality.

Isolation and Self-Discovery

Melmoth’s journey symbolizes the tension between the individual and the collective, reflecting themes of self-discovery and survival. As a sheep who ventures beyond the comfort of the flock, Melmoth is driven by a need to prove his independence and bravery.

His decision to isolate himself for five nights is both an act of defiance and an opportunity for personal growth. This quest for self-discovery becomes more profound as he faces the harsh realities of the world around him, from the unforgiving landscape to the threat of the butcher.

Melmoth’s journey is an exploration of the boundaries between belonging and freedom, as he contemplates the price of independence and whether true freedom lies in isolation or in the protection of the flock. The discovery of the human body and the butcher’s sinister role in the world add an existential layer to Melmoth’s journey, forcing him to confront the realities of death and mortality.

Through this experience, Melmoth evolves from a youthful rebel to a more introspective and self-aware individual, one who recognizes that survival often requires more than just physical endurance—it demands an understanding of the complexities of life and death. His journey exemplifies the internal struggle of balancing personal freedom with the need for connection, making it a poignant exploration of what it means to be an individual in a world fraught with danger and uncertainty.

The Limitations of Animal Understanding

In Three Bags Full, the sheep’s investigation into George’s death constantly highlights the limitations of their understanding, both of the human world and their place within it. Despite their cleverness, they are unable to fully comprehend the intricacies of human motives, desires, and emotions.

The sheep’s actions often stem from basic observations and instincts, filtered through their limited perceptions of the world. This limitation becomes apparent when they misinterpret human behaviors, especially their attempts to expose George’s death as a murder.

Their misunderstanding of human actions serves as a reminder of the vast divide between animal and human intelligence, and how the inability to communicate directly can result in misinterpretation. The sheep’s intelligence, while advanced for their species, is still constrained by their lack of understanding of human complexities.

The theme touches on the broader issue of interspecies communication and the difficulty of bridging the gap between two very different ways of experiencing and interpreting the world. This theme also questions the value of understanding when the truth is out of reach, leaving the sheep to grapple with the complexity of their situation without the ability to completely understand or control it.

Mortality and the Fragility of Life

The theme of mortality is deeply embedded in the story, especially through Melmoth’s journey and the investigation into George’s death. The sheep, while focused on solving the mystery of George’s death, are also forced to confront the fragility of life and the inevitability of death.

Melmoth’s encounter with the butcher and the discovery of the human body underscores the theme of death’s inescapability, even for those who attempt to distance themselves from it. The harshness of Melmoth’s solitary journey, coupled with the presence of death in the form of the butcher and the dead human body, paints a bleak picture of the world they inhabit.

The sheep, who are initially caught up in the excitement of solving a crime, are gradually made aware of their own mortality. This realization becomes particularly evident as they reflect on their dependence on humans and the dangers that come with it.

The inevitability of death is not only explored through Melmoth’s experiences but also through the sheep’s growing awareness of the fragility of their own existence. The sheep’s investigation, in the end, becomes more than a quest for justice—it evolves into a contemplation of the transient nature of life itself, and how death shapes the world, even in ways that are beyond their understanding.