Three Wild Dogs and the Truth Summary, Characters and Themes

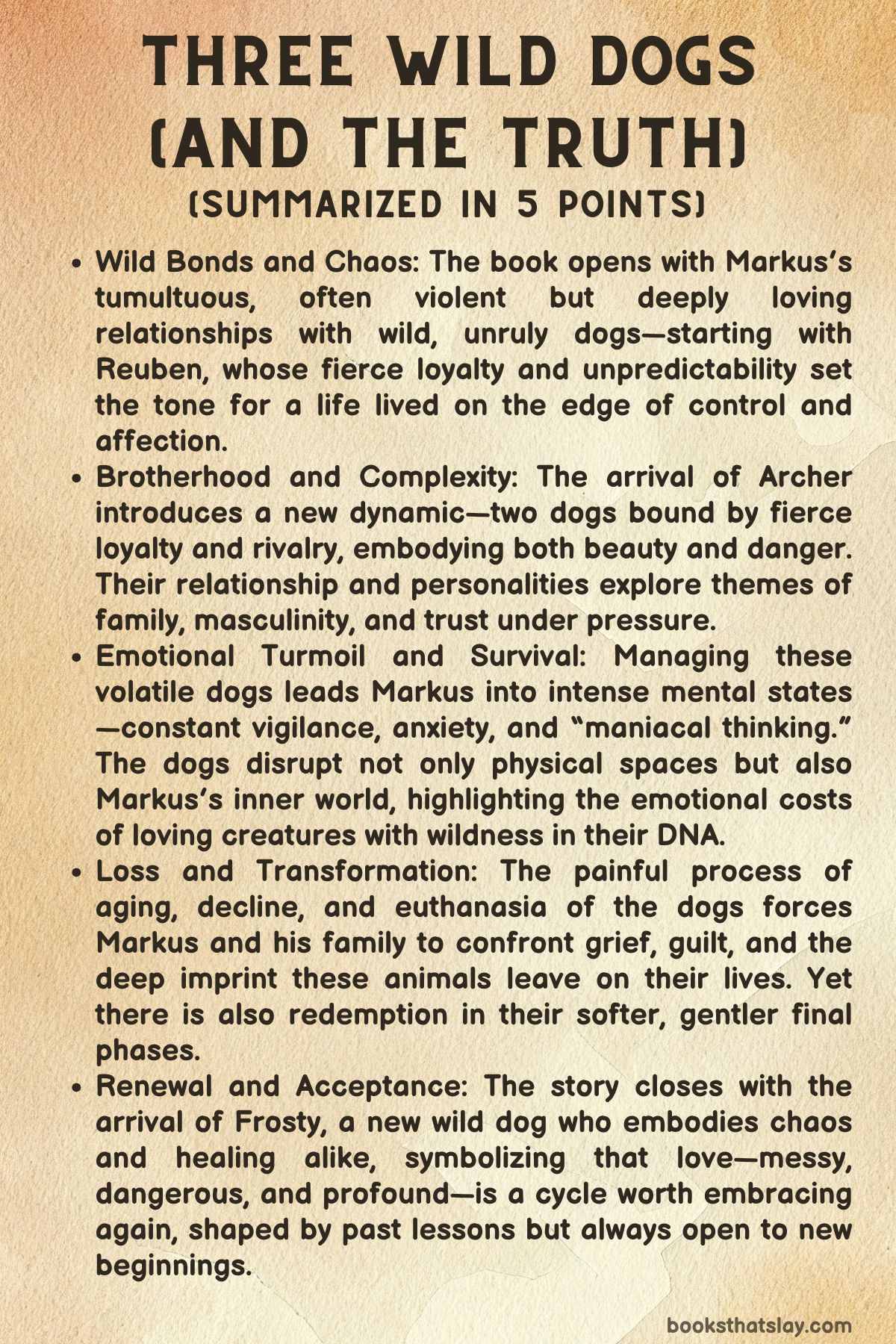

Three Wild Dogs and the Truth by Markus Zusak is a chaotic, intimate, and reflective memoir that explores the depths of love, loss, and responsibility through the author’s real-life experiences with three unforgettable dogs. Set in suburban Sydney, this story is not just about pet ownership, but about the raw complexities of life and the human condition mirrored through the unruly, loving, and sometimes dangerous behavior of animals.

Through a blend of humor, regret, and reflection, Zusak crafts a deeply personal journey that reveals how these dogs—Reuben, Archer, and Frosty—help him face his own flaws and learn what it means to fiercely love, even when it hurts.

Summary

The story opens in Three Wild Dogs and the Truth with a vivid scene of physical and emotional struggle: the author wrestling his unruly dog, Frosty, on the streets of Sydney. This confrontation, witnessed by judgmental passersby, immediately sets the tone.

Frosty is not a docile companion but a force of nature. His chaotic energy represents more than just misbehavior—it’s a reflection of something untamed inside the author himself.

This sets the stage for a narrative where dogs aren’t accessories to life, but essential players in its messiness and meaning.

Before Frosty, there were two others: Reuben and Archer. The author doesn’t sugarcoat their histories.

He critiques the language around pet adoption, rejecting the sanitized idea of being a “rescuer” and instead embracing the chaos that these animals bring. Reuben was a large, wild-eyed mutt chosen at the urging of the author’s daughter, Kitty.

He quickly became both protector and source of anxiety, loved fiercely but often unpredictable. His relationship with Kitty, who treated him like a sibling, became a touchstone.

But love didn’t erase challenges. Reuben’s behavior escalated from playful to threatening, including a terrifying moment when he lunged at the narrator’s baby son.

Despite fear and guilt, the family kept him, believing in redemption.

Part of Reuben’s complexity is revealed through a string of misadventures. From triggering dog fights in the park to knocking the author unconscious while he was wearing a baby carrier, Reuben’s presence is both a comedy and a test of endurance.

It’s not long before another dog, Archer, enters the picture. A streetwise golden dog with soulful eyes, Archer’s adoption seems serendipitous.

The family, still grieving another loss, finds hope in him. But Archer is no gentle savior.

His arrival reignites conflict, especially with Reuben, and their volatile dynamic leads to fights, vet visits, and growing anxiety.

Yet amid the violence, there is also loyalty. Reuben and Archer are destructive and unpredictable, but they are also deeply loved.

The family accepts their flaws as part of the package. This loyalty is tested again and again—when Reuben scales a tree and kills a possum, when the dogs trample the neighborhood Papillon, and, most harrowingly, when they bite the beloved family piano teacher, Lindi.

That incident nearly results in the dogs being put down, but Lindi’s compassion spares them. The narrator’s guilt is palpable.

He knows he could be judged for keeping dangerous dogs, but he chooses love over simplicity, repeatedly.

Tragedy strikes when the family’s indomitable cat, Bijoux, is accidentally killed by Reuben and Archer. The cat had been part of the family’s story from the beginning, a small, fierce presence that once ruled over both dogs and humans.

His death feels like a deep rupture—a mistake too big to ignore. The children are devastated, and the narrator reflects on the fragile lines between love and destruction that are so often blurred by the animals we let into our lives.

Eventually, the wild years calm. Reuben and Archer begin to mellow.

For a time, life is good. Morning walks, trips to the beach, quiet moments in the sun.

These years are remembered with reverence, especially Reuben’s tactile warmth and grounded presence. But by 2019, Reuben collapses unexpectedly.

A rushed emergency vet visit leads to surgery and a grim diagnosis: cancer. The family is told he has months to live.

He rallies briefly, giving them one last stretch of borrowed time, before his condition worsens. He dies at home, surrounded by his people.

The grief is immense.

With Reuben gone, Archer becomes the center of the home. Surprisingly, he thrives.

He transforms into a gentle, steady presence. He greets guests calmly, basks in the sun, and plays Monopoly with the kids.

His growth into a “gentleman” feels redemptive. Even Brutus, the elderly cat, mellows in this quieter household.

But the peace is short-lived. In 2021, Archer shows signs of decline.

When he collapses, the end comes quickly. The family surrounds him with affection and farewell.

His death, too, is a breaking point.

Left without dogs, the house feels hollow. A dogless home, once unimaginable, becomes reality.

That absence is soon filled by Frosty, a wired, explosive creature from the pound. He arrives with chaos and attitude, launching himself into the street in a fit of barking rage.

Still, the family welcomes him. They recognize something familiar in his wildness, something that links him to those they’ve lost.

Frosty brings back the noise, the destruction, the embarrassment—but also the joy. His antics, including escaping and running solo into the vet’s office, echo the madness of Reuben and Archer.

Through him, the past is both remembered and transformed.

As Frosty settles in, the narrator begins to understand the depth of what these dogs have given him. They weren’t perfect.

They caused damage. They bit, barked, destroyed, and embarrassed.

But they also loved fiercely, asked for nothing but presence, and revealed the complicated, stubborn, enduring nature of true affection. The dogs were not just part of the family—they were its pulse.

Their deaths left holes, but their legacies shaped the way the family lives and loves.

In the end, Three Wild Dogs and the Truth isn’t just about dogs. It’s about committing to imperfection, about choosing to love when it’s hard, and about the unexpected beauty that can arise from chaos.

With Frosty at his feet, the narrator looks back with gratitude. The story is not neat, but it is full.

And in that fullness—of bruises, joy, guilt, laughter, and fur—there is truth.

Key People

Reuben

Reuben stands as the towering emotional and narrative core of Three Wild Dogs and the Truth. From the moment of his introduction, he is described as part Great Dane, Mastiff, and Greyhound, but it’s the undefined wildness in him—possibly even “werewolf”—that best captures his untamed essence.

Reuben is a paradox, a creature of immense love and terrifying unpredictability. His physical strength is matched only by the depth of his bond with the narrator and the family, especially with Kitty, the narrator’s daughter.

Their connection is innocent and mythic, rooted in bedtime stories and shared chaos. Yet as Reuben grows, so too does the complexity of his behavior.

He becomes increasingly volatile, capable of threatening strangers and, most disturbingly, even turning his teeth toward the narrator’s infant son. Despite the risk, the family’s commitment to Reuben remains steadfast, fueled by loyalty and love that defy logic or fear.

His life is a study in contradiction—beautiful and brutal, hilarious and horrifying—and ultimately, his decline and death devastate the household. Reuben’s passing marks not only the end of a dog’s life but the closing of a feral, unforgettable chapter of their familial identity.

Archer

Archer’s entrance into the family brings with it both charm and chaos. He is a golden, lanky street dog with a disarming look of innocence that belies his inner savagery.

Named after a fictional street from the narrator’s then-unfinished novel, Archer embodies a kind of literary superstition—a hope that his arrival might usher in good fortune. Instead, he delivers bedlam.

He is Reuben’s volatile counterpart, his energy combustible, and their shared dynamic unpredictable. They fight, injure each other, and ignite countless disasters.

Yet Archer is never reduced to caricature. Beneath the madness is a dog of fierce devotion and sudden tenderness.

After Reuben’s death, Archer transforms in unexpected ways. He becomes a gentler presence, welcoming visitors, basking in the sun, and playing quiet games with the children.

This transformation speaks volumes about his emotional capacity and sensitivity. His own decline—quiet, creeping, and eventually fatal—is experienced with the ache of déjà vu.

Archer’s death seals another fissure in the family’s heart. He is the second great love lost, and his absence plunges the household into a dogless grief.

Archer’s character arc is rich and full, evolving from wild troublemaker to solemn guardian.

Frosty

Frosty’s arrival in the aftermath of Reuben and Archer’s deaths signals a new era of chaos and renewal. Found at a pound, he is a wiry, grey wolfhound with a feral heart and an unrelenting need to move, to moan, to disrupt.

His street fight on his first walk with the narrator becomes emblematic of his personality—loud, unpredictable, impossible to ignore. Frosty is not a replacement but a reincarnation of energy, a spiritual echo of Reuben and Archer without mimicking them.

He doesn’t fill their shoes so much as kick over the shoe rack. Through him, the narrator rediscovers the absurdity and tenderness of starting over with a new dog.

Frosty becomes a catalyst for healing, a physical embodiment of grief transmuted into momentum. While his antics—escaping to the vet solo or lunging at strangers—mirror those of his predecessors, there’s something uniquely hopeful about his presence.

He is not burdened by the memory of past dogs, but carries them with wild grace. Frosty’s uncontainable vitality becomes a gift: not peace, but forward motion, and through it, the family finds their footing once more.

Kitty

Kitty, the narrator’s daughter, is not merely a bystander to the dogs’ drama but an emotional anchor in the narrative. Her fierce love for Reuben defines his place in the family and intensifies the stakes during his “turning.

” She is imaginative and loyal, weaving bedtime stories and rituals that elevate Reuben from pet to mythic guardian. Her grief is palpable when Reuben turns aggressive or falls ill, and her resilience is tested through each traumatic incident—from the near-attack on her brother to the violent death of their cat, Bijoux.

Kitty’s interactions with the dogs offer a tender, sometimes painful glimpse into childhood innocence meeting the mess of adult decisions. Her unwavering devotion becomes one of the book’s most affecting emotional through-lines, underscoring how the dogs shaped not just the adults, but the very formation of the children’s identities.

Bijoux

Though a cat, Bijoux wields as much narrative weight and personality as any of the dogs. He is a miniature tyrant, fearless and imperious, ruling the household with dominance despite his diminutive size.

Bijoux’s lifelong defiance—against neighbor cats, invading dogs, and the odds—cements his legendary status. His eventual, accidental death at the paws of Reuben and Archer is both devastating and symbolic.

It represents the culmination of unchecked chaos and the deeply personal cost of living with wildness. Bijoux’s death is rendered with brutal honesty and emotional devastation, particularly because he had once held his own so effortlessly.

The incident leaves the family shaken, and the narrator especially grapples with the unbearable irony of having lost the one creature who refused to be cowed by the dogs. In death, Bijoux becomes a martyr of innocence and boundary.

The Narrator (Markus Zusak)

At the center of Three Wild Dogs and the Truth is the narrator himself—flawed, funny, self-deprecating, and fiercely loving. His voice threads every anecdote with raw emotion, philosophical insight, and comic absurdity.

He is not a traditional hero or even a flawless caretaker. He fails, he loses his temper, he gets concussed, and he makes choices out of fear, pride, or exhaustion.

Yet what makes him deeply compelling is his relentless honesty. His love for his dogs is never sugar-coated; it is turbulent, bruising, and absurd.

He carries guilt like a second leash—over Reuben’s aggression, Bijoux’s death, and the bite that nearly destroyed a friendship. His story is a tribute to the chaotic process of learning how to love something that bites, breaks, and ultimately dies.

Through his dogs, he comes to accept the wilderness not only within them—but also within himself.

Themes

Chaotic Devotion and the Nature of Unconditional Love

The emotional terrain of Three Wild Dogs and the Truth is shaped most strongly by the kind of love that refuses to let go, even in the face of unrelenting chaos, humiliation, and violence. The dogs in the book—Reuben, Archer, and Frosty—are not lovable in the easy, commercialized sense.

They are not Instagrammable, well-behaved pets but beings of destruction, instinct, and impulse. And yet, they are loved.

This contradiction is the heart of the story: love that is boundless but not blind, love that flinches but does not flee. When Reuben lunges at the narrator’s baby or sends him sprawling into unconsciousness in a park, the response is not abandonment but commitment.

The family chooses watchfulness over surrender, continuing to live in discomfort and risk because they believe Reuben deserves that effort. This isn’t idealistic love; it is real, exhausted, and persistent.

The dogs test boundaries constantly, and the narrator confesses his own failures—his mistakes, his shame, and his fear—without ever considering that giving them up could be a solution. Through this, love is not framed as an emotion but a series of decisions: to forgive, to protect, to endure.

The devotion extends beyond sentiment, growing teeth and claws as it adapts to wild, uncontainable lives. In this way, the story becomes a portrait of the kind of love that doesn’t demand perfection from its object, and instead survives through its willingness to stay even when staying feels almost impossible.

The Burden and Beauty of Responsibility

Throughout the narrative, the weight of being responsible for another living being—especially one with unpredictable behavior and violent tendencies—plays a defining role in the narrator’s identity. Initially taken on as a gesture of love or childhood promise, the dogs soon become full-fledged entities demanding round-the-clock vigilance, discipline, and understanding.

Reuben’s transformation from an unruly puppy into a dangerous adult forces the narrator and his family into difficult decisions: whether to keep him, how to control him, how to keep others safe. Archer’s battles for dominance and Frosty’s ungovernable energy add further complexity.

But the sense of responsibility doesn’t stop at feeding or walking—it seeps into ethical dilemmas, like lying to a park ranger after Reuben kills a possum, or navigating the guilt and horror when the dogs injure a beloved family friend. Each event forces a recalibration of moral position: what does it mean to be accountable for a creature’s actions when that creature does not comprehend consequence?

The book doesn’t offer clean answers, only the emotional residue of carrying that burden. Even when tragedy unfolds—as with Bijoux’s death—there is no shrugging of blame.

The narrator claims responsibility not with a self-righteous air but with a haunted awareness that this is part of the deal. Responsibility is not glorified here; it is painful, grinding, and often thankless.

But it is also the thing that grounds love in action, that turns chaos into loyalty, and that allows flawed beings—human and canine—to coexist within the same family.

Grief as a Living Force

Grief in Three Wild Dogs and the Truth is not limited to death—it begins with the first realization that something loved may no longer be safe. It starts when Reuben growls at Noah and when Archer begins to slow down from illness.

It simmers under the surface during every moment of dread that this walk, this fight, this injury could be the last. When Reuben finally collapses, the narrative does not dwell on his death as a singular event, but as a culmination of a thousand moments already lived with loss in the margins.

His death is profound, but what follows is equally telling: the shift in household energy, the “dogless drought,” and the aching silence that remains. When Archer, too, dies, the grief is laced with exhaustion.

There is no dramatic unraveling, just a slow, resigned heartbreak. Grief here isn’t depicted as cathartic; it’s repetitive, heavy, and absurd.

The family’s way of coping—dragging Reuben on a mattress, finding gallows humor in the worst moments, eventually adopting Frosty—is a form of survival. Even Frosty becomes a vehicle for grieving, a chaotic reincarnation of past dogs that allows memory to live on in unexpected, undisciplined ways.

The book understands that grief never leaves—it shapeshifts. It howls, knocks over furniture, moans in sleep.

It becomes part of daily life, no longer a thing to “get over” but something to carry, like dog hair in carpet or scars on a knee.

Human Identity Through Animal Companionship

At its most reflective, Three Wild Dogs and the Truth uses its stories of canine misadventure to examine human identity, particularly the narrator’s own masculinity, parenting, aging, and moral contradictions. His self-image is bound to these animals—not just in their behavior but in how he responds to them.

His inability to control the dogs in public becomes a public trial of his manhood, his self-worth, and his social standing. He is judged, mocked, and sometimes endangered, all while grappling with internal questions about what kind of man he is when faced with chaos.

Parenthood, too, is filtered through this lens. His children love these dogs without judgment, but he must mediate that love with safety, boundaries, and sometimes deception.

The narrator’s relationship with animals reveals the messy, reactive parts of himself—the failure to always protect, the temptation to lie, the sorrow of not being enough. The dogs are not metaphors, but they function as reflections of his inner wilderness.

They are his flaws made fur and bone, and through them, he examines himself with a brutal honesty that avoids sentimentality. Every ruined park bench, every lie to a ranger, every act of forgiveness becomes a microcosm of what it means to be human in a world where control is an illusion and identity is shaped less by intention than by reaction.

The book becomes a memoir not just of dogs, but of a man coming to terms with the wild contradictions of his own nature.