Too Soon by Betty Shamieh Summary, Characters and Themes

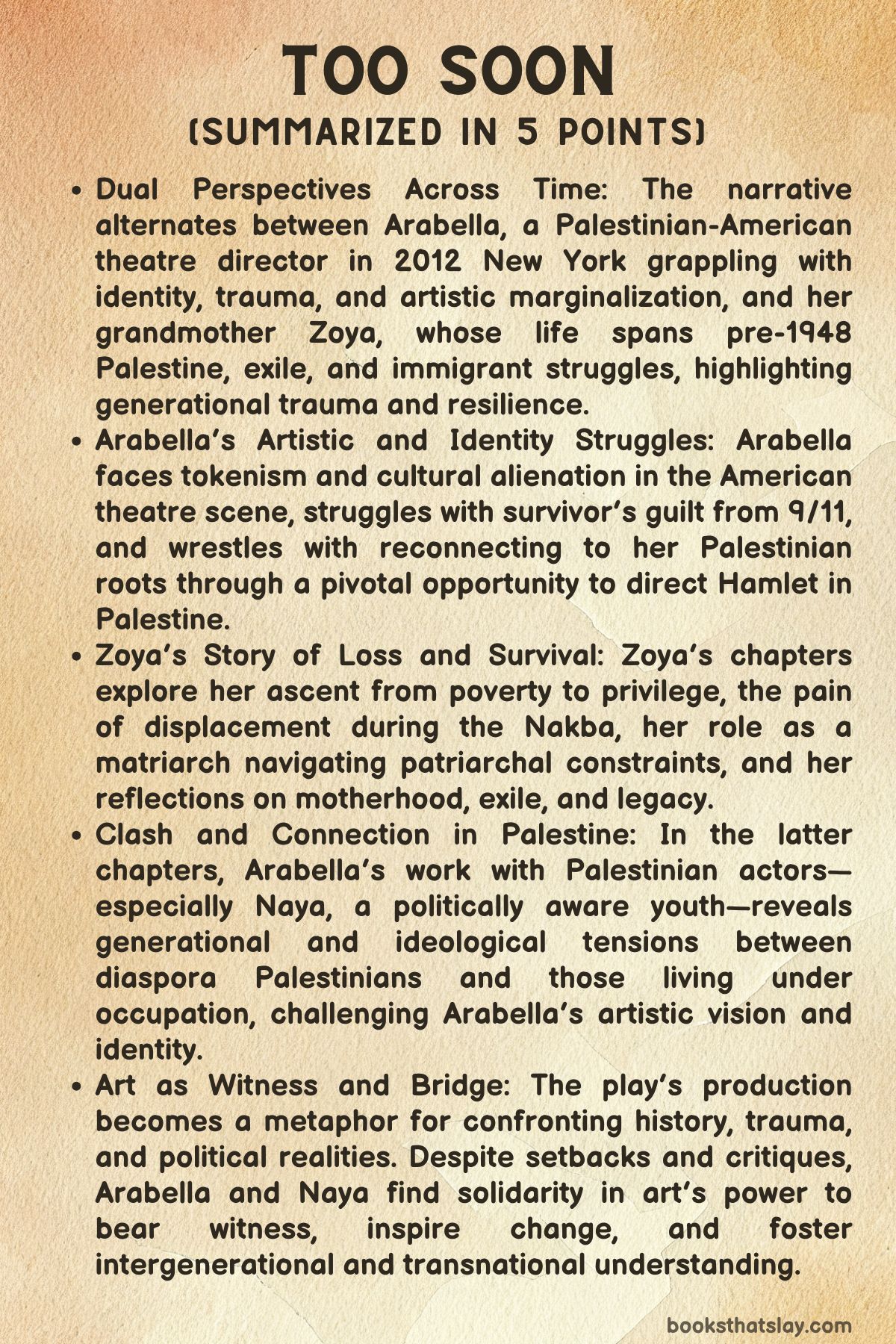

Too Soon by Betty Shamieh is a richly textured novel exploring three generations of Palestinian women across shifting geographies, wars, and diasporas. At its core, the book centers on Arabella Hajjar, a Palestinian-American theatre director whose life and art are shaped by personal grief, cultural inheritance, and political displacement.

Spanning from 1948 Palestine to post-9/11 New York and the modern West Bank, the narrative offers a layered meditation on identity, resistance, family, and the power of storytelling. Through a combination of intimate drama and broader historical context, Too Soon captures the unresolved burdens passed down through matriarchs and the personal reinventions that arise from inherited pain.

Summary

Arabella Hajjar is a Palestinian-American woman living in New York City in 2001. When the Twin Towers fall, she survives the tragedy physically unharmed, but emotionally detached.

Her disconnection from the collective trauma reveals a deeper alienation, one that stems from being both insider and outsider—a U. S.

citizen whose Arab identity places her under suspicion. As she grapples with guilt over her emotional numbness, she also confronts the shallow expressions of solidarity from the liberal arts community that surrounds her.

Though these peers claim to care about justice, Arabella senses the performative limits of their engagement, especially when it involves uncomfortable truths about race and power.

Arabella’s artistic work in experimental theatre often engages with classical texts reimagined through contemporary and cultural lenses. Despite some acclaim, she finds herself courted more for her ethnic identity than her talent.

When a white British playwright offers her the assistant director role on a Palestinian-themed play, she realizes her value is being instrumentalized. The opportunity, while seemingly progressive, reveals the racist and colonial undercurrents of the American and European theatre establishment.

Arabella’s refusal to be tokenized results in professional backlash, but she retains her dignity by later agreeing to direct a Shakespearean play in Ramallah, this time on her terms.

Her internal struggles are mirrored in her relationship with her grandmother, Zoya, a woman with a complicated past. Zoya’s life in Jaffa in 1948 was marked by love, artistic promise, and tragedy.

Her encounter with Aziz, a man she loved and lost, rekindles memories of a life interrupted by war. Zoya’s creative spark—once nourished by writing revolutionary plays—was stifled by her role as a wife and mother, and her flight from Palestine during the Nakba severed her from her creative self.

When war breaks out and the family flees Jaffa, Zoya leaves behind her notebook of plays, a symbolic abandonment of her dreams. Years later, that loss haunts her, especially when she encounters Aziz again on the boat to America.

Zoya and her husband Kamal rebuild their lives in Detroit. Assimilation is difficult, especially when being Palestinian comes with racial and political burdens.

Zoya masks her origins in public but clings to tradition at home. Her relationship with her daughter, Naya, becomes a battleground between these values.

Naya, in love with a Black man and seeking independence, defies her mother’s expectations. In response, Zoya arranges for her to marry and severs her ties to the man she loves.

This decision—meant to protect Naya from dishonor—devastates their bond. Naya’s resentment festers even as she becomes a mother herself.

Years later, Naya has become a successful woman living in Silicon Valley with her husband Daoud, only to learn that he has been unfaithful. This betrayal, compounded by a terminal illness diagnosis, forces her to reexamine her past and her priorities.

In her final months, she reconnects with Esther, a former friend whose closeness once bred jealousy. Their reunion is filled with raw honesty, as Naya confronts her own complicity in years of emotional repression and cultural rigidity.

In reconciling with Esther, she finds a sliver of peace and prepares herself to face death with grace and resolve.

Back in Ramallah, Arabella’s production of Hamlet is complicated by local politics and gender expectations. Her lead actress, Cherifa, drops out after her fiancé—encouraged by conservative pressures and the manipulative director Ramez—demands it.

Arabella is left with a choice: cancel the play or take the lead role herself. Choosing the latter, she transforms the production into Hamleta, casting herself as the lead and reconfiguring the classic tragedy into a revolutionary feminist act.

Her performance is more than theatrical—it is personal and political, a declaration of agency in a place where female autonomy is fragile.

Even as Arabella finds empowerment through art, her personal life remains fraught. Her romantic relationships, particularly with Aziz and Yoav, are shaped by questions of loyalty, betrayal, and historical enmity.

Yoav is a Jewish friend and sometime lover whose family history ties him to Arabella’s own cultural dislocation. Their connection is intimate but ultimately unsustainable, weighted by inherited trauma and conflicting narratives.

Arabella’s visit to Yoav’s mother, Indji, adds another layer to the web of generational pain. Indji, once a glamorous Egyptian Jewish woman now exiled in New York, sees in Arabella a mirror of her own contradictions.

Arabella learns of her mother’s death shortly after the success of Hamleta. Though the production garners critical acclaim and repositions her career, it is overshadowed by grief.

Arabella returns to the U. S.

to mourn and settle her mother’s affairs. Naya’s final act before dying had been to safeguard her daughter’s financial future, ensuring she would not be dependent on her estranged father.

In this gesture, Naya breaks the generational cycle of maternal coercion and silence, offering Arabella a freedom she herself never had.

Choosing to become a mother alone, Arabella pursues single parenthood through a sperm donor. Her decision is both a rejection of traditional narratives and an assertion of independence.

Though disconnected from romantic fantasy, her path to motherhood is grounded in love, intention, and resilience. With her daughter—whom she names Naya—Arabella begins a new chapter.

When she is offered the opportunity to direct Antony and Cleopatra at Shakespeare’s Globe in London, she accepts, boarding a plane with her child. The flight symbolizes transition, not only geographically but spiritually—from inherited sorrow to self-made hope.

In naming her daughter after her mother, Arabella honors the complicated lineage she comes from. Her story, shaped by trauma, rebellion, and creativity, is now interwoven with a new beginning.

As she embarks on this journey, Arabella does not seek to erase the past but to reinterpret it. Through her art, motherhood, and unyielding commitment to personal truth, she reclaims space in a world that has long tried to confine her.

Too Soon closes not with resolution, but with movement—toward autonomy, artistic fulfillment, and a legacy redefined on Arabella’s terms.

Characters

Arabella Hajjar

Arabella Hajjar is the emotional and ideological center of Too Soon. As a Palestinian-American theatre director, she stands at the intersection of multiple identities—artist, survivor, exile, daughter, and woman—struggling to define herself amid the wreckage of personal and political trauma.

Her journey is marked by internal conflict, particularly in how she processes the events of 9/11. Her muted emotional reaction to the attacks reflects a profound alienation: from mainstream American sentiment, from the expectations of trauma, and from a city that treats her both as a victim and as suspect due to her heritage.

Arabella’s career in theatre symbolizes both empowerment and erasure. Though her innovative reinterpretations of canonical texts like Hamlet showcase her brilliance, she is often reduced to a tokenized identity by predominantly white artistic institutions.

Her reluctant acceptance to direct a production in Palestine marks a turning point—from strategic self-promotion to meaningful reclamation of her heritage. When she eventually decides to cast herself in the lead role of a gender-reversed “Hamleta,” Arabella not only challenges patriarchal power structures within Palestinian society but also claims authorship over her own narrative.

Her evolution from a daughter resisting familial pressure to a single mother raising a child on her own terms in London is both an assertion of autonomy and a continuity of inherited strength. Arabella becomes the embodiment of diaspora’s pain and possibility, an artist who refuses invisibility and carves a space where her voice and history coexist with defiance and compassion.

Zoya

Zoya, Arabella’s grandmother, is a matriarch defined by exile, sacrifice, and an unfulfilled longing that spans decades. Introduced as a young woman in Jaffa in 1948, Zoya experiences the disintegration of her homeland through both public catastrophe and private heartbreak.

Her early love for Aziz, a passionate and educated man, is never consummated but remains a haunting thread throughout her life. The moment she leaves her revolutionary plays behind while fleeing Jaffa symbolizes not only the physical loss of territory but also the erasure of intellectual and artistic ambition—a trauma she never fully recovers from.

In exile, she becomes a wife, a mother of eight, and a reluctant immigrant, anchoring her family in Detroit with pragmatic endurance. Her life is shaped by the paradox of control and powerlessness: she enforces rigid cultural norms, especially on her daughter Naya, yet is unable to shield her family from racism, poverty, or generational rifts.

In her old age, she becomes a vessel of contradictions—simultaneously strong-willed and regretful, manipulative and self-sacrificing. Her final acts, including attempting to prevent an arranged marriage for Arabella and reconciling with Naya, are rooted in a belated understanding of the damage she inflicted while trying to protect.

Zoya dies haunted by what was lost—her homeland, her plays, her daughter’s trust—but leaves behind a legacy that fuels Arabella’s drive for both justice and self-definition.

Naya

Naya, the daughter of Zoya and mother of Arabella, occupies a middle generational space that embodies both rebellion and compromise. Her character is shaped by the burden of growing up under Zoya’s authoritarian parenting and the larger cultural expectations placed upon Palestinian daughters in diaspora.

Naya’s youthful defiance—falling in love with a Black American man, seeking autonomy, and refusing a traditional arranged marriage—triggers a deep familial crisis. Forced into a marriage as a means of social correction, her academic ambitions and emotional wellbeing are sacrificed in the name of cultural preservation.

This moment becomes a generational wound that defines her later relationship with Arabella. As an adult, Naya carves out a life of surface stability in Silicon Valley, managing her marriage and finances with a steely competence that belies a history of suppressed dreams and ongoing pain.

When faced with terminal illness and the discovery of her husband’s betrayal, she exercises quiet but ruthless agency—securing her daughter’s future, confronting her past, and seeking solace in long-lost friendships. Her reunion with Esther, an old friend, offers a glimpse of the woman Naya might have been: empathetic, playful, intellectually curious.

Even in death, Naya shapes Arabella’s world, both through inherited trauma and as a cautionary figure who chose survival over self-expression. Her daughter’s choice to name her own child after her speaks to a reconciliation—a recognition that Naya, despite her flaws, was a foundational part of the strength Arabella draws upon.

Aziz

Aziz serves as both a romantic ideal and a symbol of missed potential in Too Soon. His presence spans generations—first as a young medical student in Jaffa, romantically entangled with Zoya, and later as a refugee spotted aboard a ship decades later.

Aziz’s intellectual fervor and charisma contrast sharply with the domestic expectations placed on Zoya, representing the road not taken, the self that could have been nurtured under different political and personal circumstances. His gesture of returning Zoya’s lost plays—transcribed by their mentor—shows a tender recognition of her creative spirit, but it is also a futile offering, a relic of a life disrupted by war and patriarchy.

In Arabella’s timeline, he becomes an ambiguous figure of ancestral memory, cultural origin, and emotional curiosity. Whether he is fully real or partially mythologized by Arabella, Aziz represents the yearning for connection to a pre-exilic identity—romantic, intellectual, and authentic.

His inability to bridge the past with the present mirrors the broader themes of generational loss and fragmentation in Palestinian diaspora.

Yoav

Yoav, Arabella’s Jewish friend and former artistic collaborator, serves as a site of ideological and emotional tension. As a New Yorker with Israeli roots, Yoav embodies the liberal, intellectual enclave Arabella both belongs to and distrusts.

Their shared artistic past and flirtatious undercurrents complicate their relationship, especially as Arabella begins to navigate her Palestinian identity more openly. Yoav’s estranged mother, Indji, adds another layer to their dynamic, revealing the intersecting histories of exile and trauma shared by Arab and Jewish diasporas.

Arabella’s lie to Indji—claiming to be Jewish and in love with a Palestinian—reflects her ambivalence toward Yoav and her own fractured identity. Yoav’s failure to support Arabella’s choice of single motherhood and his ultimate absence from her life symbolize the limitations of even well-intentioned allyship.

He becomes a reminder that emotional intimacy, however genuine, is not always strong enough to withstand the weight of political history, cultural divergence, and the demands of self-determination.

Ramez

Ramez is the embodiment of the patriarchal and political gatekeeping that Arabella must navigate within the Palestinian artistic world. As a local theatre director, Ramez resents Arabella’s foreign funding, gendered vision, and leadership.

His attempts to seize the lead role in her production, his coercion of Cherifa’s fiancé, and his general obstructionist behavior all expose the internalized misogyny and hierarchy that exists even within resistance movements. Ramez is not merely a personal antagonist—he represents the broader societal constraints that suffocate female agency, particularly in contexts burdened by occupation and survival.

His resistance to Arabella’s reinterpretation of Hamlet is less about artistic integrity and more about preserving male dominance in both cultural and political spaces.

Cherifa

Cherifa, the talented young Palestinian actress originally cast as Hamleta, represents the intersection of personal ambition and societal pressure. Her decision to leave the production under the threat of losing her engagement reveals the limited choices available to women in patriarchal societies, even when those women are artists and visionaries.

Cherifa’s story is heartbreaking precisely because it is so common: her agency is curtailed by love, tradition, and male manipulation. Her departure forces Arabella to step into the lead role herself, turning a loss into a powerful act of reclamation.

Though Cherifa’s role in the plot is brief, her absence is felt throughout the performance—she becomes a symbol of silenced potential and the sacrifices women are forced to make.

Indji

Indji, Yoav’s mother and a former Egyptian Jewish aristocrat, is a mirror and foil for Arabella. Exiled from her homeland and living in New York, Indji shares the experience of cultural dislocation and political loss.

Her refined demeanor, cutting wit, and guarded emotional presence create a complex character who is both alluring and tragic. When Arabella visits her, pretending to be Jewish, Indji senses the deception but chooses not to confront it—perhaps out of compassion, perhaps out of fatigue.

The interaction is intimate and uneasy, a brief but resonant encounter that highlights the shared, though divergent, traumas of Jewish and Palestinian exiles. Indji’s presence challenges Arabella to reckon with the complexity of identity, love, and history, forcing her to ask whether belonging is ever truly possible in a fractured world.

Esther

Esther, Naya’s long-lost friend, is a quiet but profound presence in the novel’s final act. Her reunion with Naya is charged with emotion, not because of grand revelations, but because of the simple grace she offers.

Their renewed friendship allows Naya to reclaim a piece of her past—one that wasn’t marked by control, resentment, or duty. Esther represents the possibility of healing, of reconnecting with a self long buried under years of conformity and sacrifice.

In contrast to the betrayals Naya suffers from her husband and mother, Esther offers honesty, care, and dignity. Their time together is short but transformative, allowing Naya to face death not as a victim but as a woman who has reclaimed her agency, however late.

Through Esther, the novel insists that redemption, while never erasing the past, can still soften its edges.

Themes

Displacement and Exile

Displacement courses through the lives of multiple generations in Too Soon, beginning with Zoya’s forced exodus from Jaffa and extending to Arabella’s disoriented sense of belonging in post-9/11 New York. For Zoya, exile is sudden and violent, catalyzed by the news of the Deir Yassin massacre and the resulting panic that compels her family to flee their home.

The dislocation is both physical and symbolic—her creative identity is quite literally left behind in the form of a forgotten notebook filled with revolutionary plays. Her emotional connection to Jaffa becomes a haunting absence, one she never fully resolves even after emigrating to America.

In Arabella’s world, exile is subtler but equally damaging. She has never lived in Palestine, yet her body and identity are marked by the weight of a homeland that has been lost.

In New York, she is both insider and outsider—embraced for her talent, yet exoticized for her heritage. Whether facing surveillance in an airport interrogation room or performing self-censorship in a theatre boardroom, Arabella’s experience is shaped by a continuous negotiation with forces that question her belonging.

Displacement becomes an inherited condition, emotionally coded and carried in language, silence, and art. Even when Zoya settles into suburban Detroit or when Arabella takes a prestigious directing job abroad, home remains an unstable concept—either physically erased, politically inaccessible, or emotionally elusive.

Intergenerational Trauma and Memory

The psychological legacy of trauma unfolds across the experiences of Zoya, Naya, and Arabella, not as isolated events but as emotional patterns, silences, and inherited fears. Zoya’s memories of forced migration, personal sacrifice, and cultural shame are not buried with her—they shape how she raises her children, particularly in her punitive efforts to control Naya’s independence.

Her fear of dishonor and her internalized conservatism, born from war and exile, lead to irreversible decisions that leave Naya emotionally fractured. These maternal choices are not only personal misjudgments but historical reenactments, repetitions of the violence and silencing Zoya herself once endured.

For Naya, the trauma manifests in estrangement, resentment, and ultimately a resolve to protect her daughter from the same fate. Arabella, in turn, becomes both the recipient and breaker of this chain.

Her artistic ambitions and defiant choices—rejecting romantic compromise, choosing single motherhood, and reimagining canonical texts—signal a desire to transform inherited pain into agency. Still, she is haunted by what she carries: her grandmother’s regrets, her mother’s concealed illness, and the accumulated weight of unresolved grief.

Memory, for all three women, is not a passive recollection but an active, shaping force—something that dictates who they can become and what they must overcome. It is kept alive in gestures, unsent letters, and retold stories, binding them in complex loops of duty, sorrow, and resilience.

Female Autonomy and Resistance

Women’s choices—or their denial—anchor the emotional and political stakes of Too Soon. Zoya’s life is framed by roles imposed upon her: mother of many, dutiful wife, exiled refugee, and silent artist.

Her love for Aziz and the creative spirit she once had are quietly sacrificed at the altar of survival and social conformity. Yet even within these constraints, her resistance flickers—through withheld apologies, subversive memories, and moments of tenderness with unlikely companions.

Naya’s defiance is more visible but equally costly. Her rejection of arranged marriage and her pursuit of education and personal autonomy set her at odds with her mother’s values.

She suffers, not just from cultural repression, but from the betrayal of being handed over to it by someone who once claimed to protect her. Arabella carries this legacy of resistance forward, but her autonomy is shaped by newer battlegrounds: tokenism in the arts, gender politics in global theatre, and the subtle tyranny of professional gatekeeping.

Her decision to stage Hamlet as Hamleta is not just an artistic experiment—it is a political act. It asserts the right to reinterpret culture, to center female experience, and to occupy space historically denied to women.

Arabella’s eventual choice to raise a child alone, untethered from male validation, echoes her lineage of struggle while rewriting its conclusion. Across generations, resistance is not loud or always successful—it is quiet, persistent, and rooted in the refusal to be erased.

Art, Performance, and Identity

In Too Soon, art is not only a medium of expression but a battleground where identity, power, and truth collide. Arabella’s life as a theatre director is filled with contradictions: she is celebrated for her innovative interpretations yet marginalized when her identity challenges institutional comfort.

Her creative vision is constantly undercut by racialized and gendered assumptions. Whether being offered tokenistic roles or sidelined in favor of white male peers, Arabella must fight to be seen on her own terms.

Her production of Hamleta becomes a site of reclamation—not just of artistic integrity, but of self-definition. The act of performance—whether on stage or in daily life—emerges as both a shield and a weapon.

Arabella learns to perform grief, to rehearse belonging, to craft versions of herself palatable to others. Her internal monologues often contrast sharply with the roles she plays in public, underscoring the emotional cost of such performances.

Similarly, Zoya’s early attempts at writing plays are stifled by circumstance, yet the rediscovery of her notebook years later reveals how vital and suppressed that creative impulse once was. The story proposes that storytelling—whether through dramatic monologue or family lore—is a radical form of survival.

In staging and restaging their truths, these women resist the narratives imposed upon them. Art becomes a place where they can control the spotlight, reframe the ending, and assert a legacy that is not defined by loss but by the audacity to speak.

Love, Loss, and Ambiguity

The emotional lives of the characters are marked not by romantic closure, but by persistent ambiguity. Zoya’s love for Aziz is never consummated in a traditional sense, but it lingers across decades as a what-if that colors her perception of self and sacrifice.

Their reunion aboard the ship is both tender and confrontational, filled with longing, bitterness, and a shared recognition of roads not taken. Similarly, Arabella’s relationships with Yoav and Aziz are framed more by uncertainty than fulfillment.

Her dynamic with Yoav is complicated by unspoken attraction, political difference, and unresolved histories. With Aziz, she faces the impossible pull of heritage and romance, unsure whether she is drawn to him as a man or a symbol.

Even Naya, in her final days, reflects on a life punctuated by betrayals, missed chances, and the quiet companionship she finds at the end with Esther. Love in this story is never pure or redemptive; it is entangled with exile, power, and compromise.

These characters do not find solace in happily-ever-afters but in fleeting connections, hard-won clarity, and the messy, often painful, endurance of emotional truth. The novel refuses sentimental resolutions, offering instead a vision of love as something unstable yet deeply human—an experience that shapes identity without defining destiny.

Loss, too, is never singular. Each death, each departure, reverberates through time, reminding the characters that even in separation, emotional ties remain intact, unresolved, and enduring.