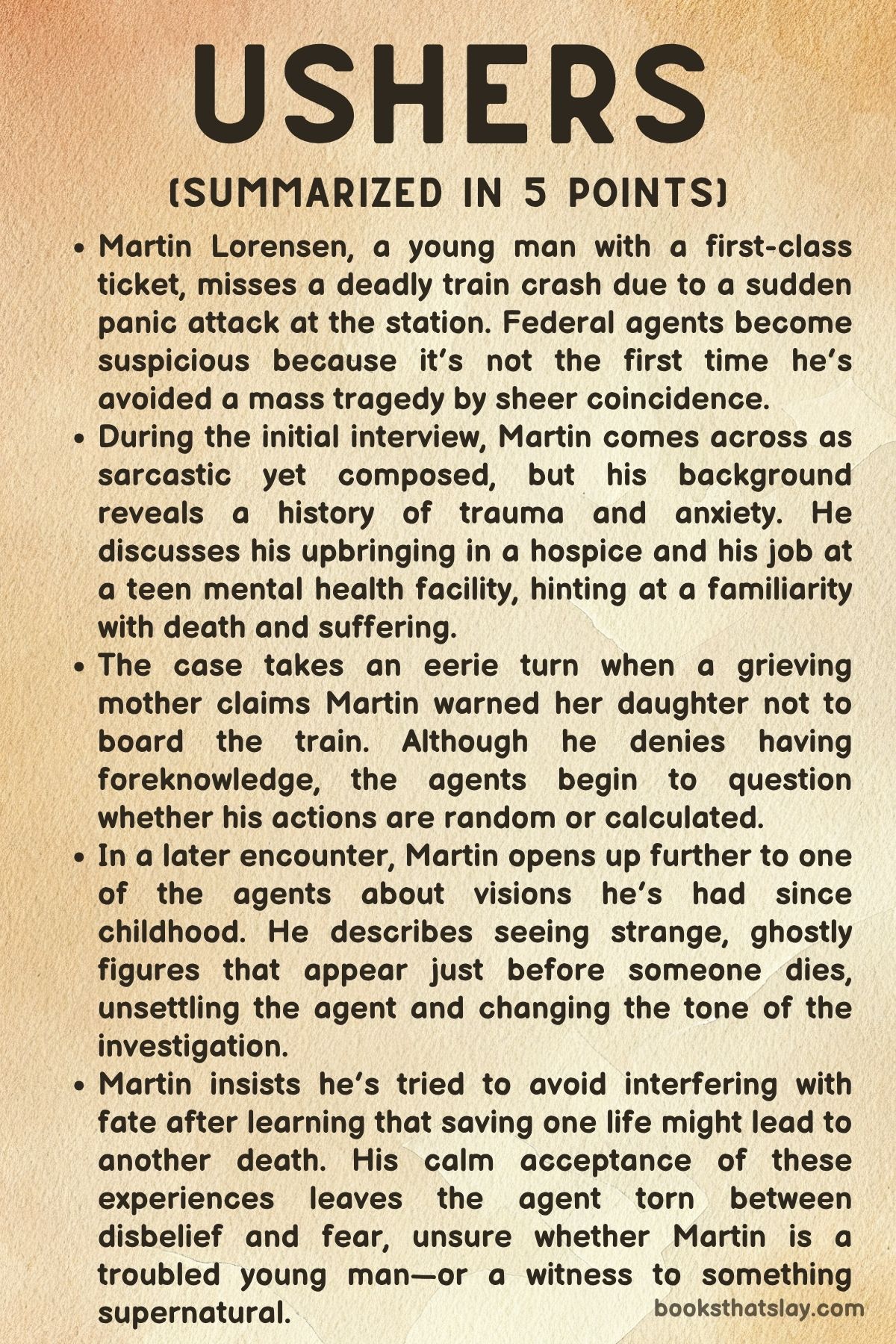

Ushers by Joe Hill Summary, Characters and Themes

Ushers by Joe Hill is a compact yet haunting short story that straddles the line between psychological mystery and supernatural horror. The story revolves around a series of interrogations with a young man named Martin Lorensen, who appears to have narrowly escaped multiple tragedies—most recently, a deadly train crash.

What begins as a standard federal inquiry soon spirals into unsettling territory as Martin reveals a secret that reshapes the agents’ understanding of reality and death. Through sparse settings and intense dialogue, Hill explores themes of fate, trauma, and the invisible threads connecting life and death, all within a tightly packed narrative that lingers well after its conclusion.

Summary

The story begins with Special Agents Anthony Duvall and John Oates conducting a formal interview with a twenty-three-year-old man named Martin Lorensen. Martin has caught their attention due to his unusual survival of the Mohawk 118 train crash—a disaster that killed twenty-eight people.

He was supposed to be on that train, and his last-minute decision not to board raises suspicion. Martin claims he had a panic attack just before boarding and chose not to go.

His explanation is rational on the surface, but Duvall senses something deeper at play. This isn’t the first time Martin has had a close brush with tragedy.

Years earlier, he avoided a school shooting in his hometown, another instance where he seemingly escaped death at the last moment.

Martin’s demeanor is complicated. He is intelligent and quick-witted, casually referencing philosophy and literature, which throws off the agents at first.

His tone is often laced with irony, bordering on dismissive, but there’s a consistent undercurrent of unease. As the interview progresses, the agents begin probing into Martin’s recent interactions—especially with a teenage girl named Audrey Giovanni and her mother, who were also supposed to be on the Mohawk 118 but disembarked shortly before the crash.

This coincidence seems too convenient. Martin initially denies warning them, but Duvall suspects otherwise.

After the formal interview ends, the agents meet Martin again for an informal, off-the-record conversation. This second meeting is more relaxed, taking place in a more social setting and stripped of official protocols.

Here, Martin becomes more candid. He admits to warning Audrey but insists he did so not because of foreknowledge in the traditional sense, but because of a gut feeling—a powerful, undeniable certainty that something terrible was going to happen.

That’s when he shares something even stranger: since childhood, he has seen mysterious figures he calls “ushers.

Martin describes the ushers as humanoid but not entirely human. They have pigeon wings and wear ash-covered cassocks, giving them the appearance of grim, angelic figures.

They appear to him whenever someone is about to die, not speaking, but always present at the moment of passing. The first time he saw one was during a volunteer stint at a hospice center with an elderly patient named Mrs.

Keats. She died shortly after Martin saw the usher standing beside her.

The apparitions are terrifying, but over time Martin has come to accept their presence as a constant—a grim confirmation of fate’s finality.

Things took a darker turn when Martin once tried to intervene. During college, he saw an usher next to a young woman who had epilepsy.

He warned her, and she survived the imminent seizure that might have killed her. However, the usher then appeared again, this time before a young girl who was run over and killed right in front of Martin.

This event changed his understanding of the ushers. He became convinced that their purpose is not to punish or reward but simply to ensure death arrives where it is supposed to.

If he interferes, death does not retreat; it simply shifts.

The story begins to question whether Martin is a clairvoyant, a traumatized young man suffering from psychosis, or a reluctant prophet burdened with knowledge that no one else can comprehend. Duvall, though trained to approach everything with logic and reason, starts to feel deeply unsettled.

Martin’s descriptions are vivid and convincing—not the typical ramblings of someone imagining things. And Martin’s calm acceptance of this morbid truth only makes it harder to dismiss him.

When the second meeting ends, Martin declines a ride and walks off into a thunderstorm, preferring solitude. Duvall and Oates drive off in silence.

Duvall is deep in thought, replaying Martin’s final comments—particularly his warning that someone must die to balance the lives that were spared. Audrey and her mother survived the crash because Martin intervened.

Someone else, he said, would have to take their place.

Then comes the chilling climax. As the agents drive into the storm, Duvall begins to feel uneasy.

He glances into the back seat and sees two ushers sitting quietly behind them. One has copper-colored eyes and gently places a hand on Oates’ shoulder.

The other leans in toward Duvall and whispers in his ear, “Hold on, Tony, something wonderful is coming. ” The implication is immediate and clear—death is imminent.

The story ends on this unresolved but harrowing note, suggesting that the agents’ fates are now sealed. Whether Martin’s visions are supernatural truths or delusions shaped by trauma, their effects are all too real.

The appearance of the ushers confirms that Martin wasn’t merely imagining things. Duvall, who once viewed Martin as possibly disturbed, now becomes the next witness to the phenomena Martin has described for years.

Ushers plays with ambiguity throughout its brief but intense narrative. It never fully confirms whether the ushers are real, but the story strongly implies that Martin’s experiences reflect a horrifying reality that cannot be explained through conventional logic.

It focuses less on action and more on dialogue, mood, and the eerie psychological space between knowing and fearing. In doing so, it captures the terror not of death itself, but of its inevitable claim—and the burden of being able to see it coming.

Characters

Martin Lorensen

Martin Lorensen is the enigmatic heart of Ushers. At twenty-three, he embodies a contradiction—a boyish, fresh-faced man whose whimsical charm conceals an abyss of trauma and dread.

From the outset, Martin’s personality is marked by sardonic wit and literary flair, evoking both sympathy and suspicion. He casually drops references to Viktor Frankl and existentialism, revealing a sharp, introspective mind that has been shaped by a lifetime of unusual experiences.

Beneath this intellectual bravado, however, lies deep psychological turmoil. His self-professed panic attacks and social awkwardness suggest a man grappling with chronic anxiety, made more complicated by his bizarre visions.

Martin’s past is a tragic tapestry of brushes with death. He missed a deadly train crash due to a panic-induced decision, much like a previous close call during a high school shooting.

These patterns of survival are more than coincidence; they are the portals through which the supernatural enters the story. He reveals in the second, more candid interview that he sees ethereal beings he calls “ushers”—figures in soot-streaked cassocks with pigeon wings—whenever death is imminent.

For Martin, these beings are not hallucinations but spiritual certainties. His attempt to intervene in their rituals, once saving a woman only for a little girl to die in her place, leaves him with a grim understanding: death cannot be stopped, only redirected.

This resignation shapes his moral ambiguity. Is Martin a hero trying to warn others, or a danger himself, tempting fate by meddling in its design?

His final moments in the story—declining a ride, walking into the rain, and disappearing from view—underscore his ghost-like quality. Martin exists on the margins of both life and death, sanity and prophecy.

Whether he is a prophet cursed with apocalyptic foresight or a delusional man haunted by trauma, the story never resolves. Instead, Martin remains a chilling symbol of the thin line between the knowable and the unknowable, between witnessing death and causing it.

Anthony Duvall

Special Agent Anthony Duvall is the analytical and deeply introspective counterpart to the chaos Martin brings into his world. He is introduced as a skeptical investigator, trained to detect deceit and disarm misdirection, yet his journey through Ushers peels back layers of guarded professionalism to expose something more vulnerable and human.

Duvall’s initial approach to Martin is one of suspicion; he senses that Martin is withholding something profound and potentially dangerous. His interview technique is precise and strategic, pressing Martin to reveal what lies beneath his glib exterior.

Yet, as the story progresses, Duvall becomes less certain of his own judgments. His skepticism is gradually worn down by Martin’s eerie accuracy, unsettling confessions, and the disquieting plausibility of the supernatural explanation.

In the second interview, Duvall loosens the restraints of official protocol, choosing a bar over a briefing room, signaling a shift from interrogator to confidant. His psychological armor begins to crack under the weight of Martin’s conviction.

By the end, Duvall is not just an agent seeking truth—he is a man confronted by the limits of rationality.

His final experience, when he sees the ushers in the back seat just before a near-fatal crash, blurs the boundary between belief and madness. The whisper in his ear, “Hold on, Tony, something wonderful is coming,” marks a profound transformation.

Duvall, once the symbol of empirical clarity, becomes a vessel of supernatural suggestion. His arc reflects a descent—or elevation—into a realm beyond reason, where logic gives way to eerie acceptance.

His character is ultimately a meditation on what happens when the empiricist confronts the inexplicable and cannot turn away.

John Oates

John Oates serves as a foil to both Martin Lorensen and Anthony Duvall in Ushers. A fellow agent, Oates embodies grounded practicality, often acting as a stabilizing presence during the interviews.

While less introspective than Duvall, Oates is crucial in anchoring the story in realism. His reactions to Martin’s bizarre claims are marked by a blend of procedural detachment and subtle unease, suggesting that while he may not overtly believe in the supernatural, he is not entirely immune to its implications.

Oates’ most significant narrative function occurs in the story’s climax. In the back seat of the car, just before the near-collision, one of the ushers gently touches his shoulder—a gesture that feels both intimate and ominous.

The physicality of this moment sets Oates apart; while Duvall receives a whisper, Oates is marked by contact. It implies that he, too, has been chosen or acknowledged by these death-foretellers.

Though the story does not fully explore Oates’ internal state, his presence highlights the ripple effects of Martin’s revelations. Oates may not voice his beliefs, but the usher’s touch suggests a transformation—quiet, irrevocable, and deeply personal.

Ultimately, Oates is the everyman figure in the narrative. He reflects how the unimaginable can touch even those who resist it.

His silent presence and final encounter with the ushers serve as a chilling reminder that belief is not always required for the supernatural to act. His character anchors the story’s eerie ambiguity, making the final turn all the more haunting.

The Ushers

The titular ushers in Ushers are not conventional characters in the human sense, but their presence looms over every scene like a metaphysical shadow. Described as angelic figures with pigeon wings and cassocks stained with soot, they are both grotesque and holy—paradoxes that mirror the story’s exploration of life and death.

They function not as harbingers of doom but as facilitators of it, appearing when someone is about to die. Their calmness and quiet gestures—touching shoulders, whispering reassurances—make them even more terrifying.

They do not scream or wield weapons; they simply arrive, and that is enough.

For Martin, the ushers are constants in his life. From his youth at a hospice to a crowded train platform, their arrival signifies the inescapability of fate.

They are immune to human appeal and operate by laws unknown to the living. When Martin once dared to save someone fated to die, the usher retaliated by killing another, reinforcing a cold cosmic order: death must have its due.

This transactional, even bureaucratic, view of mortality imbues the ushers with terrifying neutrality. They are not evil, but they are not merciful either.

Their final appearance, during the story’s climax, confirms their power over all the characters, including the skeptical Duvall. Their cryptic whisper and chilling calmness transform the story from a psychological thriller into something far more metaphysical.

The ushers are not just characters—they are the embodiment of inevitability, entities beyond comprehension, reminding readers that death, however delayed, is never denied.

Themes

Inevitability of Death

In Ushers, death is presented not as a random occurrence but as a predetermined event that cannot be escaped or erased. Through Martin Lorensen’s experiences, death is revealed to operate like a system—mechanical, deliberate, and unyielding.

Martin’s encounters with supernatural entities known as “ushers,” who appear before someone dies, remove the possibility of death being entirely unpredictable. These ushers do not just witness death; they ensure it happens.

The story challenges the assumption that human intervention can always avert tragedy. When Martin once tried to save a girl from death, another died in her place.

This unbalanced exchange turns death into a transactional inevitability rather than a preventable accident. Even well-meaning interference becomes ethically ambiguous: saving one life simply reallocates death’s target, not its presence.

Martin’s resignation to this system emphasizes the helplessness individuals face in the shadow of fate. Despite his intelligence and heightened awareness, he remains powerless to change outcomes.

The agents’ growing unease in the face of Martin’s calm fatalism underscores the oppressive certainty that death cannot be bargained with. Even for those who don’t see the ushers, like Duvall and Oates, the consequences unfold inescapably.

The final car crash and Duvall’s eerie interaction with the ushers suggest that once chosen, one cannot hide from death’s approach. The story’s view of mortality offers no comfort—it is not an end earned or deserved, but an unavoidable constant, one that haunts both the living and the dying with equal cruelty.

Burden of Foreknowledge

The psychic toll of knowing what is to come—especially when it involves suffering and loss—is a central preoccupation of the narrative. Martin’s ability to see the ushers, and thus know who is about to die, isolates him from others.

He is forced to carry information that most people are never meant to have. This burden creates a chasm between him and the rest of the world, making even casual social interaction laced with hidden trauma.

His refusal to board the Mohawk 118, the warning he gives Audrey, and the confession to the agents all highlight a man trapped between revealing too much and protecting others from a truth that offers no relief.

Foreknowledge in Ushers is not empowering—it is a curse. Martin’s visions do not allow him to prevent death, only to witness it before it occurs.

He is condemned to live with the guilt of choosing whether or not to intervene, fully aware that any attempt to reroute fate comes with collateral damage. This knowledge doesn’t just set him apart psychologically; it renders him morally paralyzed.

Every action—or inaction—has a cost, and the story suggests there is no correct way to handle such a gift. Even when he chooses to speak out, as with Audrey and her mother, he cannot stop the ushers from demanding a soul.

His visions, rather than being divine or prophetic, trap him in a purgatory of responsibility without power. The toll this takes on his psyche is profound, contributing to his sardonic, anxious demeanor, and deep sense of alienation.

The burden of foresight becomes indistinguishable from psychological trauma, haunting him as much as the deaths he foresees.

Ambiguity of Sanity and Belief

Martin’s credibility is a persistent question throughout the narrative, and Ushers maintains a deliberate ambiguity over whether he is experiencing hallucinations or a supernatural reality. His articulation, literary references, and flashes of philosophical insight position him as highly intelligent, but his history of anxiety and trauma introduce doubt into the agents’—and the reader’s—perception of his mental state.

His visions could be symptoms of a disordered mind attempting to impose structure on chaos, or they could be genuine glimpses into a spiritual realm that defies explanation.

The story leaves this tension unresolved, inviting readers to occupy the uncomfortable space between rational skepticism and mystical acceptance. Duvall’s shift in perspective, from professional detachment to deeply unsettled belief, mirrors the reader’s progression.

What begins as a procedural interview morphs into an existential confrontation with the unknown. The ushers’ final appearance in the agents’ car suggests that Martin’s experiences may not be delusional after all.

However, because the story never definitively affirms the supernatural, it keeps the door open for interpretation: are the ushers real, or has Duvall been psychologically primed to see what Martin believes?

This ambiguity deepens the psychological resonance of the narrative. It captures the fear that comes not only from death but from the inability to discern what is real.

Martin may be a prophet, a victim of untreated mental illness, or both. The story challenges conventional binaries of sanity and delusion, truth and fiction, urging a more fluid understanding of reality—especially in the face of grief, trauma, and mortality.

The lack of clarity itself becomes a source of horror, reinforcing the idea that certainty is a luxury few can afford.

Ethical Complexity of Intervention

The moral questions surrounding intervention and responsibility permeate the choices Martin makes throughout the story. While at first he claims his panic attack caused him to avoid the doomed train, the full picture later emerges: he warned Audrey, knowing that doing so might change who would die.

His confession to the agents that death must be satisfied introduces a horrifying dilemma—whether one has the right, or even the duty, to intervene if the cost is another innocent life.

Ushers doesn’t propose a clear ethical framework. Instead, it highlights the impossible moral arithmetic Martin faces.

If saving one person leads to another’s death, is doing nothing the only ethically neutral choice? Or does choosing inaction make him complicit in death?

The story refrains from guiding the reader toward a definitive answer. Instead, it frames intervention as a morally ambiguous act: well-intentioned, emotionally driven, but laden with unintended consequences.

When Martin saved a college girl, only to witness a child die moments later, the devastating emotional fallout convinced him that his interference was not noble, but selfishly hopeful.

This complexity extends to the agents, especially Duvall, who must confront the implications of Martin’s worldview by the end. Duvall’s own impulse to dismiss Martin’s warnings is challenged when he sees the ushers for himself.

In that moment, he too becomes a reluctant participant in this ethical labyrinth. The story implies that once someone is made aware of death’s approach, they carry a burden of choice—and no matter the decision, innocence is lost.

Through Martin’s struggle, the story asks whether moral responsibility has any meaning in a world where death always balances the scale.