Vantage Point Summary, Characters and Themes

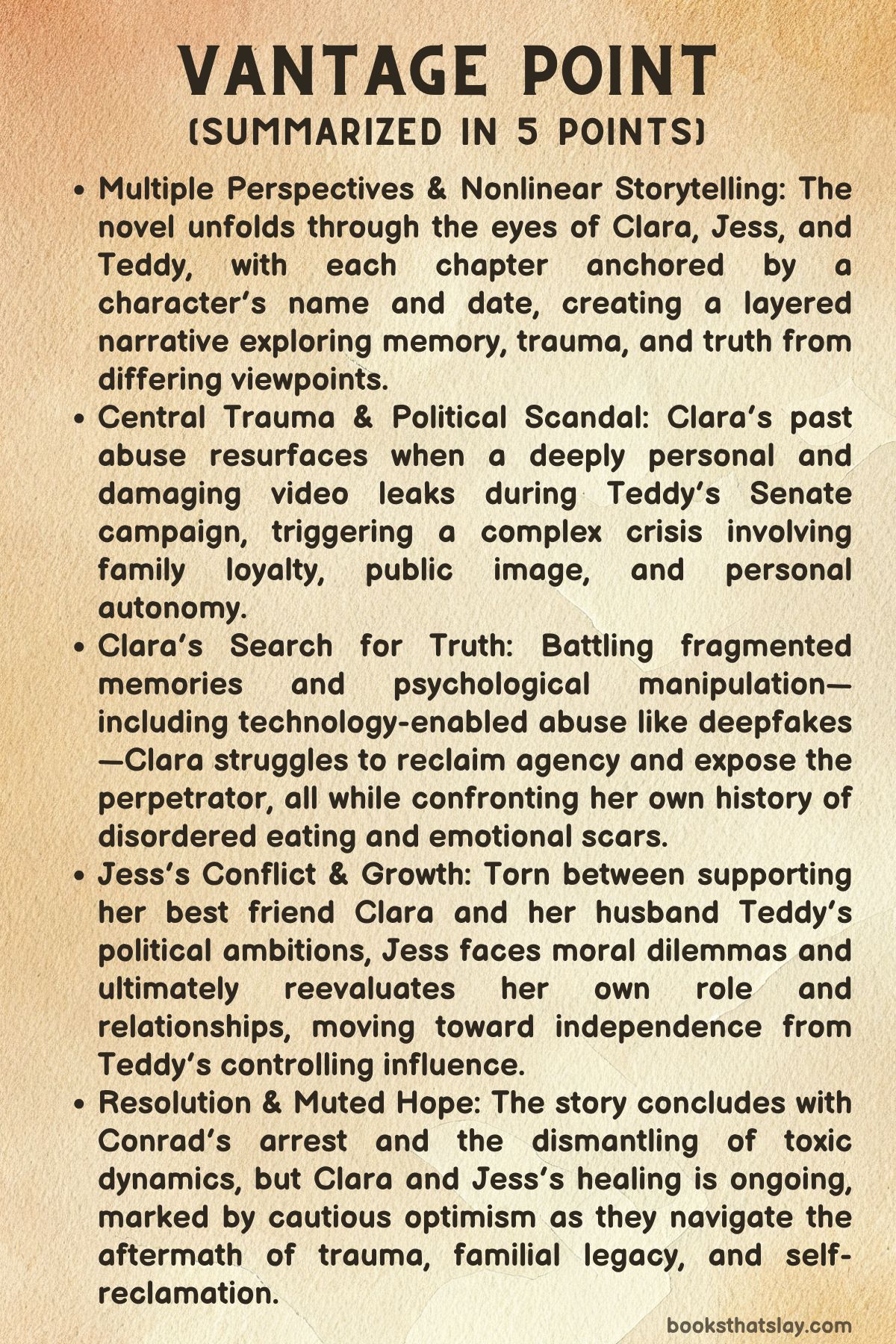

Vantage Point by Sara Sligar is a chilling exploration of identity, power, memory, and technological manipulation within a wealthy American political dynasty. At its core is Clara Wieland, a woman entangled in her family’s public legacy and private dysfunction.

The novel draws the reader into Clara’s increasingly unstable reality following a traumatic public scandal, revealing the long shadows of generational trauma and gendered expectations. Through the dual perspectives of Clara and her sister-in-law Jess—Clara’s childhood best friend now married to her brother—the book examines emotional dependency, gaslighting, and betrayal against a backdrop of deepfake technology and political ambition. Sligar constructs a psychological drama where nothing is as it seems, and the most dangerous threats may be those hiding in plain sight.

Summary

The novel opens through Clara Wieland’s perspective in a prologue that introduces her inner turmoil with a harrowing, poetic meditation on drowning. This moment, rich with metaphor, highlights her lifelong struggle with disorientation, trauma, and the deceptive calm of appearances.

Her voice is brittle, haunted, and steeped in exhaustion, setting the tone for a narrative in which memory, perception, and trust are constantly under question.

In the main timeline, Clara is temporarily running the family’s philanthropic foundation while her brother, Teddy Wieland, campaigns for Senate. Teddy is charismatic and confident, while Clara is anxious, distrustful, and weighed down by unresolved trauma and a strained sibling dynamic.

Jess, Teddy’s wife and Clara’s childhood best friend, serves as an intermediary between them. The opening scenes of daily island life contrast the familial tension simmering just beneath the surface, made worse by Clara’s internal struggles with disordered eating and a deep fear of losing control.

A family myth about a curse that brings tragedy every April looms in Clara’s mind, lending a sense of inevitability to the events that follow.

The turning point comes on April 1, when a sex tape featuring a much younger Clara goes viral online. Clara is stunned, unable to remember the encounter or the man in the video.

Her confusion and shame deepen as she considers the possibility of being raped or manipulated. While Teddy and Jess scramble to contain the political fallout, Clara sinks into a maelstrom of uncertainty, humiliation, and fear.

The public exposure forces her to confront the long-standing erasure of her autonomy by her family and society. No longer able to separate myth from reality or public perception from private truth, Clara begins to break down mentally and emotionally.

Simultaneously, Jess’s perspective reveals the layered nature of her bond with Clara. Their friendship began in childhood, when Jess was an outsider looking in on the golden, wealthy world of the Wielands.

Jess idolized Clara, immersing herself in her life and ultimately marrying her brother, Teddy. However, even from the start, Jess was aware of their differences in class and security.

As teenagers, Clara often undermined Jess’s confidence and choices, sometimes subtly and sometimes openly. When Clara went to boarding school without telling Jess she had applied, the betrayal stung deeply.

Jess had to apply in secret and was rejected due to financial constraints, cementing her position as an outsider within the family.

As the tape spreads and Clara refuses to recall or address it clearly, Jess is caught between empathy and disillusionment. Clara’s self-destruction—including showing up drunk to a political dinner—exposes Jess to public humiliation and personal heartache.

While Jess still sees Clara as wounded and deserving of compassion, she is increasingly aware of Clara’s manipulative behavior. Their relationship, once built on mutual admiration, becomes entangled in resentments, guilt, and secrets.

Jess realizes that being married to Teddy has meant absorbing not just his ambitions but also the emotional weight of Clara’s chaos.

Meanwhile, the narrative introduces Conrad, Teddy’s enigmatic former roommate and a brilliant but morally ambiguous tech developer. Conrad is working on a visual projection tool called NatureEye.

Clara has vague, disturbing memories of seeing things—visions of animals, her parents, ghostly figures—and begins to suspect she’s being manipulated. Her fears are confirmed when she discovers a projection strip hidden in Conrad’s belongings.

She begins to piece together the horrifying truth: the hallucinations may have been staged, not signs of her unraveling mind.

A confrontation between Clara and Jess exposes the deep fracture in their friendship. Jess accuses Clara of exploiting her and treating people like pawns.

Clara insists she’s trying to understand what’s happening to her. The emotional crescendo leaves them both emotionally battered.

Jess has spent years buffering Clara’s damage, and Clara realizes that even her sincerest attempts to reach out were filtered through the distortions of technology and mistrust. When Clara refers to an apology Jess never received, Jess realizes it was a hologram, not a real gesture.

Clara, determined to expose Conrad, sets a trap. She gets him to confess that he created the deepfake sex tape and manipulated her with holograms.

Knowing that tech crimes are hard to prosecute, Clara stages a scene—planting evidence and self-inflicting an injury—to make it appear as if Conrad assaulted her in a robbery gone wrong. The plan succeeds, and Conrad is arrested and convicted.

But the victory is pyrrhic.

In the wake of the arrest, Teddy becomes increasingly unstable. He is consumed by paranoia, convinced that Jess and Clara are conspiring against him.

After seeing another hologram—this one of Jess and Clara appearing intimate—Teddy assaults Jess, leaving her severely injured. He flees by boat, and Clara follows him in a final confrontation that results in his drowning.

In the aftermath, Jess survives physically but is emotionally scarred. Clara transforms the family estate, Vantage Point, into a recovery clinic.

It’s a gesture toward healing, a way to repurpose pain into purpose. Yet Jess, in her private mourning, uses the NatureEye projector to recreate an idealized Teddy—a kind, caring version that never truly existed.

The implication is that Jess, too, has succumbed to the seduction of illusion.

In the closing pages, Jess reflects on how technology, memory, and perception can create new realities indistinguishable from truth. She hints that the entire narrative—perhaps even her voice—could be an illusion, a projection, a manipulation.

It’s a final unsettling reminder that in this world, shaped by privilege, ambition, and technology, nothing is completely trustworthy—not even the story you think you’ve been told.

Characters

Clara Wieland

Clara is the psychological and emotional nucleus of Vantage Point, a character whose inner landscape is as stormy and layered as the ocean imagery that frames much of the novel. From the outset, Clara is introduced as a woman on the edge—both literally, as she stands poised at the precipice of physical danger, and metaphorically, as she grapples with overwhelming trauma and a fractured sense of self.

Her life is marked by a persistent struggle with memory loss, disordered eating, self-doubt, and an inescapable legacy of familial dysfunction. Her role at the Wieland Fund is a reluctant acceptance of familial duty, where she is both indispensable and overshadowed by her brother Teddy.

Clara’s deep insecurity, paired with sharp intelligence and seething resentment, manifests in her need to control the narrative around her—until that control is shattered by the release of a non-consensual sex tape. This moment becomes a turning point, plunging her into a spiral of shame, paranoia, and disassociation.

Yet beneath the chaos lies a resilience that culminates in her calculated takedown of Conrad, the orchestrator of the deepfakes. Clara emerges as a deeply flawed but profoundly human character—capable of tenderness, manipulation, rage, and eventual clarity.

Her transformation of the family estate into a recovery center signals a symbolic and literal reclamation of her identity and her inheritance. Clara’s arc is one of survival—not from a singular trauma, but from a lifetime of being gaslit, underestimated, and haunted by ghosts both familial and technological.

Jess Wieland

Jess is a study in contradiction: loyal yet exhausted, empathetic yet increasingly disillusioned, and ultimately heartbroken by the people she loves most. Introduced initially as a bridge between Clara and Teddy—wife to one, best friend to the other—Jess’s narrative expands to show the burdens of emotional caretaking and the silent toll of being caught between competing loyalties.

Her childhood attachment to Clara is deeply romanticized, shaped by awe and longing, but that dynamic is fraught with class disparity and emotional imbalance. As she matures, Jess grapples with the painful realization that her idealized vision of Clara may never have matched reality.

Her love for Teddy is born in Clara’s shadow, and despite her efforts to maintain harmony, she becomes a casualty of the Wieland family’s dysfunction. Jess’s patience wears thin as Clara spirals and Teddy unravels, culminating in physical violence that shatters their family unit.

After surviving Teddy’s attack, Jess’s final act—recreating a holographic version of her husband—is deeply poignant. It reflects her inability to fully detach from the image of love, even as the man himself proved monstrous.

Jess’s journey is one of disillusionment, as she learns that devotion can both save and destroy, and that memory and technology can blur the line between mourning and delusion. She is a deeply compassionate character whose arc captures the anguish of watching the people you love become strangers.

Teddy Wieland

Teddy is the embodiment of charm, charisma, and control—a political golden boy whose polished exterior masks a volatile core. He thrives in the public eye, maneuvering effortlessly through campaigns and conversations, yet he maintains a patronizing grip on his sister Clara and subtly dominates his wife Jess.

While outwardly affectionate and jovial, Teddy’s underlying traits are deeply manipulative. He dismisses Clara’s concerns with condescension, prioritizes optics over truth, and values reputation above personal well-being.

His unraveling begins with the release of the sex tape and spirals further under the weight of Conrad’s betrayal. The revelation that Teddy has been unknowingly manipulated by holograms destabilizes him completely, leading to delusional accusations against Jess and culminating in a violent outburst that nearly kills her.

His final act—fleeing by boat and drowning in a confrontation with Clara—echoes the family’s mythic curse and completes his descent from adored public figure to tragic cautionary tale. Teddy represents the danger of unchecked male privilege, the fragility of constructed identities, and the devastating consequences of emotional repression.

In the end, he becomes the symbol of a legacy that cannot be rebranded or redeemed—only ended.

Conrad

Conrad is the novel’s phantom puppeteer, a character who operates largely in the background until his technological manipulation is fully revealed. As Teddy’s old college roommate and a brilliant if sociopathic technologist, he weaponizes cutting-edge projection and deepfake technology to exploit vulnerabilities within the Wieland family.

His motivations are murky—part vengeance, part intellectual experiment—but his impact is seismic. Conrad’s use of simulated realities creates an atmosphere of pervasive uncertainty, where hallucination and memory can no longer be trusted.

He effectively gaslights Clara into questioning her sanity and orchestrates events that sabotage Teddy’s campaign and personal life. Yet Conrad’s downfall comes through Clara’s cunning—a reversal of power that reflects her growth and determination.

Despite his high-tech methods, Conrad is ultimately a character of obsession and hubris. He believes in his superiority and underestimates Clara’s resolve.

His arc serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unregulated technology, the ethics of consent in a digitized world, and the terrifying ease with which reality can be distorted. In many ways, Conrad is the ghost in the machine—the embodiment of how power, when divorced from empathy, becomes a tool of ruin.

The Wieland Parents (Posthumous Presence)

Though deceased, Clara and Teddy’s parents loom over the story as both spectral figures and thematic anchors. Their legacy—shrouded in whispers of a familial curse—colors every interaction and decision made by the siblings.

Clara’s hallucinations of them, particularly the eerie scene involving their reappearance on the island, blur the line between memory and manipulation. Their influence is most acutely felt in Clara’s constant struggle with identity and inheritance, particularly through the symbolic “Transformation” boat—a vessel both literal and figurative, built by her father and grandfather.

The parents’ death, like everything else in the Wieland mythology, is wrapped in mystery and misfortune, reinforcing the notion that their children are doomed to repeat a cycle of trauma and downfall. Their presence, even in absence, shapes the psychological and emotional landscapes of the living characters, and the lore surrounding them cements the book’s gothic undertones.

Themes

Memory and the Unreliability of Perception

Throughout Vantage Point, memory serves as both a narrative engine and a site of conflict, destabilized by trauma, manipulation, and technology. Clara’s fragmented recollections—especially concerning the sex tape she cannot remember—illuminate how deeply trauma can distort or erase key events.

This cognitive dissonance becomes even more complicated when she begins to suspect that some of her experiences, including deeply emotional visions of her dead parents, may not be hallucinations but technological fabrications. This uncertainty forces both Clara and the reader to question the reliability of perception itself.

The introduction of Conrad’s holographic technology compounds this instability, weaponizing Clara’s trauma and blurring the boundary between memory and illusion. Even Jess, once confident in her perspective, begins to doubt the authenticity of her experiences.

The final twist—that the narrative itself could be a simulation—underscores the fragility of human perception and the ease with which it can be manipulated. In a world where even memories can be manufactured, memory no longer offers comfort or clarity but instead becomes a battleground of doubt and deception.

This erosion of trust in one’s own mind isolates Clara further, as her sense of reality dissolves under both psychological pressure and technological gaslighting.

Power, Gender, and Political Optics

Clara’s role as the reluctant steward of the Wieland Fund places her within a realm of elite institutions traditionally dominated by men, where expectations are both rigid and gendered. Teddy’s casual dominance over both the family legacy and Clara’s professional life reveals how power is often inherited and enforced through charisma rather than competence.

Jess, too, is trapped in a political performance, expected to present an image of supportive wife and discreet operator while managing private allegiances to Clara. The scandal around Clara’s leaked tape exposes not just personal trauma but the ruthless calculus of political image-making.

While Clara reels from emotional devastation, Teddy and his advisors respond with immediate concern for optics, polls, and reputational damage. The irony is stark: Clara’s bodily autonomy is violated, yet the public concern revolves around Teddy’s campaign.

This imbalance reflects a broader societal dynamic where women’s pain is often sidelined in favor of preserving male ambition. Clara’s own attempts to reclaim control—particularly in her eventual framing of Conrad—subvert this imbalance but also raise troubling questions about the cost of justice and who must bear it.

The theme interrogates the ways gender and power intersect with public scrutiny, showing how women are often treated as collateral in political warfare.

Familial Legacy and Inherited Trauma

The Wieland family’s so-called curse functions as more than superstition; it becomes a deeply rooted belief system that explains and perpetuates cycles of emotional devastation. Clara, more than anyone, feels bound to this inheritance.

Her constant return to the myth of doomed Wielands reflects an internalized sense of fatalism. Teddy, by contrast, externalizes this legacy into ambition, branding the family name as something noble and saleable.

Jess, once an outsider, comes to see the curse as a metaphor for the damage caused by proximity to privilege and unresolved grief. The deaths, scandals, and mental illness plaguing the family take on an inevitability that mirrors real-world patterns of generational trauma—cycles of harm passed through behaviors, silences, and unacknowledged suffering.

Clara’s emotional breakdowns and disordered eating are not simply individual pathology; they are responses to a system of familial pressure and denial. Even Jess’s eventual physical and emotional collapse under Teddy’s violence suggests that inherited trauma is not confined to bloodlines—it radiates outward, affecting anyone caught in the Wieland orbit.

In the end, Clara’s transformation of the family estate into a recovery clinic represents both a symbolic and literal attempt to break the cycle, to turn a space of legacy into one of healing.

Female Friendship and Emotional Imbalance

The relationship between Clara and Jess is marked by intensity, interdependence, and a profound imbalance that shifts over time. Initially, Jess idolizes Clara, seduced by her wealth, beauty, and charm.

Their early bond feels all-encompassing, but it is shaped by unequal access to power and agency. Clara often controls the narrative of their friendship, sometimes casting Jess as a loyal sidekick rather than an equal.

These dynamics grow more fraught as the women age and encounter adult responsibilities, secrets, and betrayals. Jess’s marriage to Teddy complicates her loyalty to Clara, turning their bond into a tightrope act between sisterhood and self-preservation.

Clara, increasingly unstable, oscillates between needing Jess’s unconditional support and manipulating it. Jess, for her part, begins to see Clara not just as wounded but as exhausting, a person whose crisis always overshadows others.

Their final confrontation, in which Jess accuses Clara of emotional selfishness, reveals a friendship deeply eroded by years of caretaking and unmet expectations. Yet there is still love there—a love that cannot undo the imbalance but persists despite it.

The novel does not offer neat resolutions but rather acknowledges how female friendships, especially those formed in youth, can both nourish and deform over time when one person is always reaching and the other always retreating.

Technology, Surveillance, and Emotional Manipulation

The use of projection technology and deepfakes is not merely a plot device in Vantage Point, but a thematic examination of how easily reality can be manufactured and exploited. Conrad’s holograms simulate not just visual trickery but emotional experiences—Clara’s visions of her dead parents are potent precisely because they meet a desperate emotional need.

This makes the manipulation all the more violating. Unlike simple surveillance, which observes, this technology invades and scripts reality, allowing perpetrators to craft entire experiences for their targets.

The horror lies not just in being watched but in being puppeteered. For Clara, whose grasp on reality is already tenuous due to trauma, the projections function as psychological traps, reinforcing her own feelings of instability.

Jess’s later use of the projector to recreate Teddy underscores how seductive these simulations can be. Even when one knows the image is false, the comfort it provides can be irresistible.

In this way, the novel critiques the emotional economy of digital manipulation, asking what it means to seek solace in unreality. By the end, technology becomes not just a tool for deception but a mirror reflecting each character’s desire to reclaim what they’ve lost, even if it means embracing illusion.

Consent, Shame, and Public Exposure

Clara’s confrontation with the leaked sex tape and her lack of memory surrounding it raises urgent questions about consent, trauma, and the digital age’s invasive appetite for scandal. Her inability to recall the encounter, combined with visible signs of distress in the video, places her in a chilling limbo—she cannot definitively say what happened, but she feels the violation deeply.

The legal and emotional frameworks around her experience fail her at every turn. Teddy’s political operatives treat her trauma as a PR nightmare.

Jess wants to help but is constrained by conflicting loyalties. Clara is left to suffer the shame and alienation of being publicly consumed and privately disbelieved.

This is exacerbated by her own history of disordered eating and disassociation, which blur the lines between body and self. The novel portrays consent not as a binary but as a fragile, often retroactive negotiation with memory and power.

It also critiques the public’s complicity in this dynamic—how easily people consume, judge, and discard private suffering when presented in the form of viral content. Clara’s ultimate decision to frame Conrad not only seeks justice but reflects her refusal to remain a passive victim.

The narrative confronts the corrosive effects of shame and the difficulty of healing in a world where the private can never again be truly reclaimed.