Warrior Girl Unearthed Summary, Characters and Themes

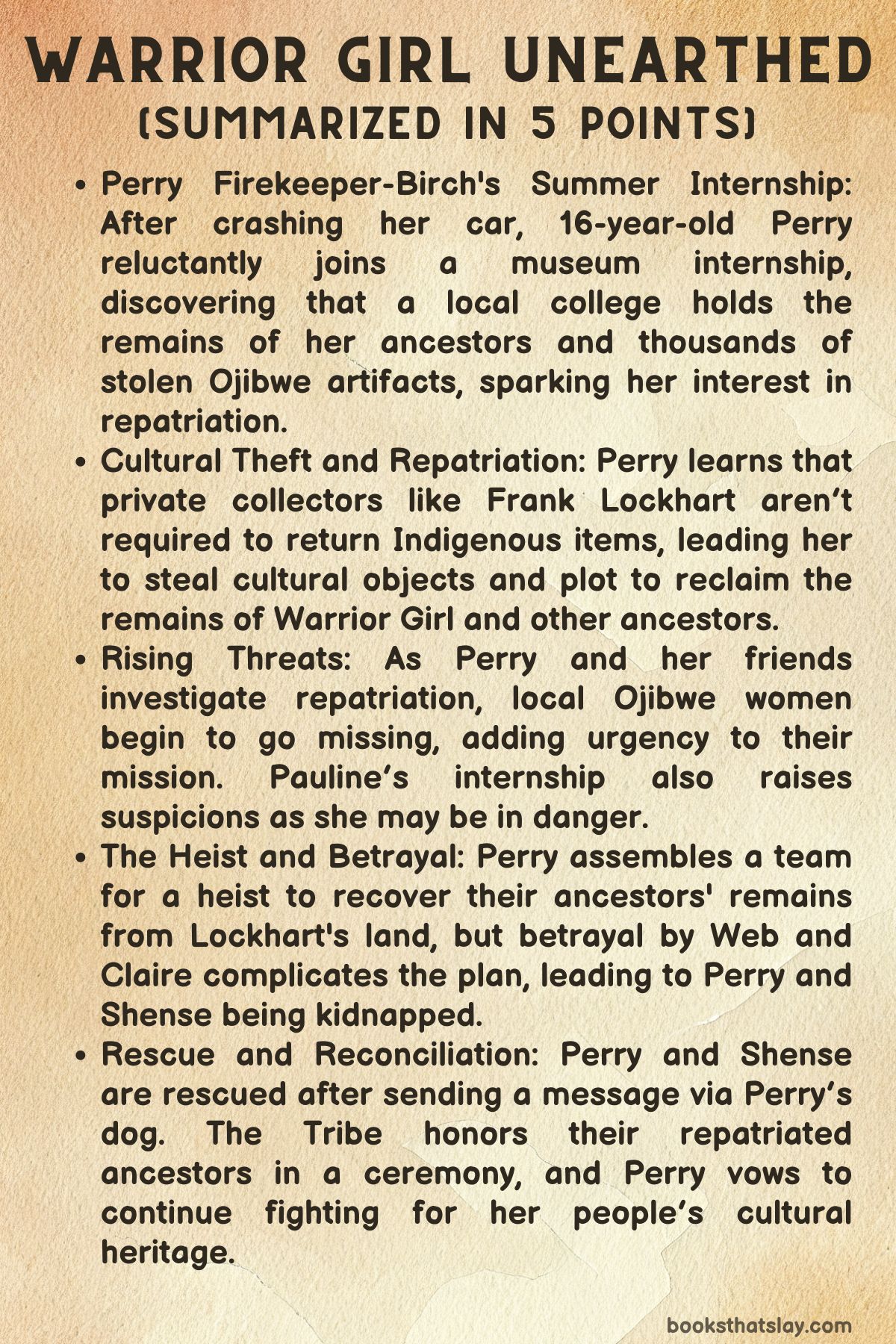

“Warrior Girl Unearthed” by Angeline Boulley is a 2023 young adult mystery-thriller set in Michigan’s Sugar Island, home to the Ojibwe Tribe. The story centers on Perry Firekeeper-Birch, a 16-year-old who uncovers a dark web of cultural theft, repatriation struggles, and the rising danger surrounding missing Indigenous women.

Through a summer internship that connects her to her ancestors’ stolen remains, Perry, along with her twin sister Pauline and friends, takes on a dangerous mission to reclaim their heritage while uncovering secrets that threaten the present safety of their community. This gripping narrative highlights activism, identity, and survival.

Summary

Perry Firekeeper-Birch, a Black and Anishinaabe 16-year-old, finds herself in a summer internship after crashing her car and needing to repay her Aunt Daunis for the damage.

While her twin sister, Pauline, secures a high-profile internship with Chief Manitou and the Tribal Council, Perry joins the museum program, led by the eccentric “Kooky Cooper” Turtle.

Her fellow interns, dubbed “Team Misfit Toys,” include childhood friend Lucas, new arrival Erik, and schoolmate Shense.

Initially uninterested in her position, Perry’s perspective shifts after a trip to Mackinac State College, where she discovers the anthropology department has kept 13 ancestors’ remains and thousands of cultural artifacts from her Tribe.

Moved by the remains of Warrior Girl, Perry feels a strong desire to take back what belongs to her people, but for now, she settles on stealing heirloom pumpkin seeds from an anthropologist’s office, planting them in her father’s garden.

Perry learns that private collectors, like local shop owner Frank Lockhart, aren’t bound by the same laws as federally funded institutions. While browsing Lockhart’s shop, Perry and Erik find Ojibwe cultural items improperly displayed, including a basket made by Perry’s great-grandmother.

This theft leads to tension between Perry and Erik, who is shocked by her actions.

Meanwhile, the community is shaken as local Ojibwe women go missing, adding a chilling layer of urgency.

Pauline’s internship with the Tribal Council takes a dark turn when Daunis suspects Chief Manitou of having inappropriate intentions toward Pauline. As Perry continues her work, she’s reassigned to Subchief Tom Webster, or “Web,” who informs her that Lockhart plans to donate his artifacts back to the Tribe.

Perry and her team interview local Elders about black ash basket making and uncover how cultural practices were lost due to forced assimilation policies. In a daring move, Perry breaks into the college office to steal black ash baskets to return to the rightful families.

A twist occurs when Lockhart betrays the Tribe by donating his collection to Mackinac instead. Chaos ensues when Perry finds Edwards, a board member and Daunis’s rapist, murdered.

Though Daunis is initially accused, another suspect is arrested. Erik and Perry reconcile, but Perry’s investigations deepen when she uncovers that Lockhart’s land may be hiding even darker secrets.

She discovers the remains of 42 ancestors displayed grotesquely in shadow boxes on his property. Determined to return them to their rightful resting places, Perry enlists her friends for a high-stakes heist.

The heist takes a dangerous turn when Shense goes missing, becoming one of the many abducted Indigenous women.

Perry and Erik confront betrayal, as Web and Claire were manipulating them from the start, using them for their own gain. After Perry is kidnapped and held in a dark pit alongside Shense, they manage to send a message tied to her dog, leading to their eventual rescue.

As the story closes, the Tribe holds a ceremony to honor the repatriated ancestors, and Perry looks toward a future dedicated to fighting for her people’s heritage.

Characters

Perry Firekeeper-Birch

Perry, the protagonist of Warrior Girl Unearthed, is a 16-year-old Black and Anishinaabe girl, struggling to find her place in her community and family. Initially portrayed as somewhat apathetic and less driven than her twin sister Pauline, Perry’s growth throughout the novel is deeply tied to her increasing awareness of the historical and ongoing oppression of her people.

After a car accident forces her into a summer internship, she becomes involved with “Team Misfit Toys,” a group of other teens working for the Tribe. At first disinterested in her work at the local museum, Perry’s discovery of her ancestors’ remains and cultural artifacts in the hands of a nearby college awakens her sense of responsibility and purpose.

This becomes a turning point for her character as she transitions from passive observer to someone actively engaged in repatriation efforts. Perry’s journey is marked by her passion and emotional investment, especially when she becomes fixated on the remains of “Warrior Girl,” a figure she identifies with deeply.

Her rebellious spirit, seen when she steals heirloom seeds and a cultural basket, demonstrates her willingness to challenge authority for what she believes is right. Despite her flaws, such as occasional impulsivity and naivety, Perry emerges as a strong-willed young woman who learns to channel her anger and grief into a constructive effort to reclaim her people’s heritage.

Her close relationship with her twin Pauline, though strained at times, also reflects her deep love for her family and community. By the end of the novel, Perry finds herself more aligned with her cultural roots, planning to pursue a career in museum studies to continue the work of repatriation.

Pauline Firekeeper-Birch

Pauline, Perry’s ambitious twin sister, is a clear contrast to Perry in terms of personality and life goals. While Perry is more laid-back and impulsive, Pauline is serious, driven, and focused on her future, interning with the Chief of Tribal Council, Chief Manitou.

Her ambition often puts her at odds with her twin, though their bond remains a significant emotional anchor for both. Pauline’s internship with the Tribal Police introduces her to the darker aspects of their community, including the exploitation of Indigenous women and the corruption in leadership.

She becomes suspicious of Chief Manitou’s intentions, especially after Daunis warns that he may be grooming Pauline, reflecting her awareness of the complexities of power and authority in their world. Pauline’s role in the story becomes even more critical during the heist to recover their ancestors’ remains.

She is an essential part of “Team Heist Misfits,” but also ends up caught in a web of manipulation by Web and others. Her admission of participation, recorded without her knowledge, becomes leverage used against her, reflecting her vulnerability despite her apparent strength.

While Pauline’s ambition sometimes blinds her to the emotional undercurrents affecting her family and friends, by the novel’s end, she remains a key figure in their fight for justice and repatriation. She stands beside her sister in the tribe’s cultural recovery.

Erik Miller

Erik is a newcomer to Sugar Island and Perry’s love interest. His character adds complexity to Perry’s personal and emotional growth.

Initially, he comes across as charming and curious about Perry’s world, but his background, particularly his probation for hacking his high school’s website, hints at a rebellious streak that aligns with Perry’s own defiance of authority. Erik’s relationship with Perry is strained after she steals a cultural item from Lockhart’s shop, revealing their differing views on law, property, and cultural ownership.

Erik is placed in a precarious position when Web coerces him into driving the moving van for the heist, despite his probation. This moment highlights Erik’s vulnerability and his desire to support Perry, though it also creates tension in their relationship.

His head injury during the heist leaves him incapacitated, but his loyalty to Perry and willingness to risk himself for her cause solidify his role as a supportive, if conflicted, character in her journey. His presence in the story adds a layer of interpersonal conflict and demonstrates the broader implications of getting involved in Indigenous issues as an outsider.

Daunis Firekeeper

Daunis is Perry’s aunt and a central figure of wisdom and guidance in her life. Having experienced deep personal trauma—she was raped at 19 by Grant Edwards, one of the novel’s antagonists—Daunis embodies resilience.

Her own story intertwines with Perry’s journey as she pushes Perry toward responsibility and involvement in the Tribe’s issues. Daunis’s knowledge and suspicion of the ongoing corruption within the community, especially regarding Chief Manitou, reflect her deep-rooted understanding of the complexities surrounding power and justice.

Her advice to Pauline about being wary of Manitou’s grooming shows her protective instincts and the hard-earned wisdom she has acquired through her struggles. Daunis also plays a pivotal role in the novel’s resolution when she is arrested for Grant Edwards’ murder, though later released.

Her final revelation of her pregnancy represents hope and continuity for her family and the Tribe. This emphasizes the theme of generational healing and renewal in the face of historical trauma.

Lucas Chippeway

Lucas is a childhood friend of the twins and a member of Team Misfit Toys. As a Native teen, Lucas shares a strong connection with the community’s cultural heritage and history, though he often expresses this connection in a quieter and less confrontational way than Perry.

His role in the heist is significant, as he joins the effort to reclaim the remains of their ancestors. Lucas’s participation reflects his deep commitment to his community and his willingness to risk his safety for the cause.

His close relationship with his great-grandmother, Granny June, underscores the importance of intergenerational knowledge and the transmission of cultural values within the Tribe. Though Lucas doesn’t take center stage in the novel’s emotional conflicts, his steady presence and loyalty to his friends and family mark him as an essential figure in Perry’s support system.

Shense Jackson

Shense is another intern and part of Perry’s group. Her role takes a dramatic turn when she becomes one of the novel’s missing Indigenous women, a central issue in the plot.

Shense’s disappearance and captivity highlight the novel’s focus on the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women. Her resourcefulness, as seen when she records messages for her daughter while imprisoned, reflects her strength and determination to survive.

Shense’s experience is a stark reminder of the very real dangers faced by Indigenous women. Her eventual rescue, alongside Perry, symbolizes the broader fight for justice and protection of their community’s most vulnerable members.

Web (Subchief Tom Webster)

Web is initially seen as an ally to Perry, working with her on the repatriation of artifacts. However, his character becomes more complex and morally ambiguous as the story progresses.

Web’s manipulation of both Perry and Erik, using recordings to coerce them into continuing the heist, reveals his self-serving motives. Though he appears to be helping with the repatriation efforts, his true intentions align more with personal gain than with the preservation of the Tribe’s cultural heritage.

Web represents the corrupt elements within their community, exploiting the goodwill of others for his own ends. His actions force Perry into difficult moral and ethical decisions, marking him as a critical antagonist in the novel’s broader examination of power and exploitation.

Chief Manitou

Chief Manitou is a political figure in the Tribe, and his interactions with Pauline suggest a hidden darkness in his character. Daunis warns Pauline that Manitou may be grooming her, hinting at a history of manipulation and abuse of power.

Though not a major character in terms of screen time, Manitou represents the corrupt and toxic leadership that pervades some aspects of the Tribal Council. His character is a reminder that not all threats to Indigenous communities come from outside forces; internal power struggles and abuses are just as dangerous.

Drs. Fenton and Leer-wah

These two characters represent the institutional forces that Perry fights against in her quest to repatriate her ancestors’ remains. Dr. Fenton, who stalls the repatriation process, and Leer-wah, who is ultimately revealed to be the captor of Perry and Shense, are embodiments of academic and colonial exploitation.

Their refusal to return Indigenous remains and artifacts, as well as Leer-wah’s violent aspirations to kidnap the descendants of the Thirteen Grandmothers, show the continued colonial violence that Perry and her community face. They serve as primary antagonists in the novel’s critique of the exploitation of Indigenous peoples and cultures by both individuals and institutions.

Frank Lockhart

Frank Lockhart is the owner of Teepees-n-Trinkets, a shop that traffics in cultural artifacts. His personal grudge against Grant Edwards, Daunis’s rapist, fuels much of the novel’s conflict.

Lockhart’s decision to donate his collection to Mackinac College instead of the Tribe further cements his role as an antagonist. His shop, which improperly displays and sells cultural items, is a symbol of the commodification and exploitation of Indigenous heritage.

While his actions propel the heist plot, they also underscore the broader issue of who controls and profits from Indigenous culture and history.

Granny June and Minnie Manitou

These two Elders play vital roles in the heist, recruited to handle the remains of the babies, as people of childbearing age cannot. Their inclusion in the heist reflects the deep respect for Elders within Indigenous communities, as they are keepers of cultural knowledge and traditions.

Granny June’s and Minnie’s involvement also underscores the intergenerational fight for justice, as they physically and symbolically aid in reclaiming their ancestors’ remains. They represent the continuity of tradition and the importance of ancestral memory in the fight for cultural survival.

Themes

The Interconnectedness of Historical Trauma and Contemporary Injustice

In Warrior Girl Unearthed, Angeline Boulley intricately weaves together the enduring trauma of colonization with the ongoing marginalization of Indigenous communities. The novel emphasizes that the struggles of the Ojibwe people—whether through the theft of ancestral remains, the desecration of cultural artifacts, or the rise in missing and murdered Indigenous women—are part of a larger, systemic injustice that stretches back centuries.

Perry’s realization that her ancestors’ bones and sacred objects are still being held by institutions highlights the deep connection between the past and present. This suggests that the legacies of colonization are not mere historical footnotes but persistent, living realities.

This theme deepens as Perry, her sister Pauline, and their friends uncover secret plots that endanger both their present-day community and the memory of their ancestors. The novel critiques institutions like museums and private collectors who continue to profit from Indigenous suffering, drawing a clear line between historical exploitation and modern-day systemic racism and marginalization.

The Complex Nature of Resistance and Cultural Reclamation

The theme of cultural reclamation is at the heart of Perry’s journey, but Boulley complicates the notion of resistance. She shows how acts of reclamation are fraught with ethical dilemmas and emotional costs.

Perry’s desire to “steal” Warrior Girl’s remains and return them to her community symbolizes a deep yearning for justice and cultural restoration. However, it raises the question of what lengths one must go to in order to right historical wrongs.

The heist to recover the ancestors from Lockhart’s property serves as a metaphor for the complexities of reclaiming lost heritage. Perry’s struggle between the right to reclaim her ancestors and the legal ramifications of doing so questions whether traditional channels for justice, such as NAGPRA, are sufficient.

The novel explores the moral gray areas of resistance—particularly when personal ethics, community loyalty, and legal frameworks are at odds. Through Perry’s actions, Boulley challenges the reader to consider what constitutes justice for communities whose heritage has been commodified and stolen, and what ethical compromises might be necessary to reclaim what was taken.

The Fragile Intersection of Trust, Power, and Exploitation within Communities

One of the more nuanced themes in Warrior Girl Unearthed is the exploration of trust and power dynamics within Indigenous communities. The novel reveals how figures of authority, like Chief Manitou and Subchief Web, can exploit their positions for personal gain, manipulating the younger generation in ways that echo broader patterns of colonial exploitation.

Daunis’s concern that Chief Manitou is “grooming” Pauline, as well as Web’s coercion of both Perry and Erik, illustrates how power can be abused even within close-knit communities. These internal tensions reflect a larger vulnerability, where those who should protect cultural values and people can be swayed by greed or personal vendettas, as seen in the Lockhart-Edwards subplot.

The theme interrogates how historical power imbalances continue to ripple through Indigenous communities. The betrayal Perry and Pauline experience from figures like Web underscores the fragility of trust, emphasizing how easily power can be corrupted even in spaces that should offer safety and solidarity.

The Intersection of Gender, Violence, and Silence in Indigenous Communities

Boulley’s novel brings attention to the brutal and often silenced realities of violence against Indigenous women. As local Ojibwe women go missing and Shense is revealed as one of the latest victims, the novel confronts the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW) head-on.

The novel doesn’t treat this violence as an isolated issue but situates it within a broader context of gendered violence that has been historically ignored or minimized by authorities. The silence surrounding these crimes—both within the community and in the larger justice system—speaks to the systemic neglect Indigenous women face.

Perry’s discovery of the bodies of missing women alongside her ancestors in the dark hole symbolizes how Indigenous women’s lives are often devalued in both life and death. The novel critiques the way Indigenous women are rendered invisible by both the state and sometimes even by their communities, calling for a collective reckoning with these ongoing acts of violence.

The Intergenerational Transmission of Knowledge and Trauma

Boulley intricately examines how trauma and knowledge are passed down through generations in Indigenous families. This is particularly explored through Perry’s relationship with her ancestors and the Elders in her community.

The loss of cultural knowledge, especially regarding black ash baskets, due to the legacy of forced assimilation and boarding schools underscores how colonization fractured cultural continuity. This theme plays out as Perry and her friends interview Elders about their connection to these cultural traditions.

The novel is also about the resilience of intergenerational transmission. Perry’s journey to recover her ancestors is a form of reclaiming both the tangible and intangible aspects of her heritage, suggesting that even in the face of immense historical trauma, there are ways to reconnect with and preserve Indigenous knowledge.

The novel ends on a note of hope, as Daunis’s pregnancy introduces a new “warrior girl” to the family. This symbolizes the endurance of culture, strength, and memory across generations.