Water by John Boyne Summary, Characters and Themes

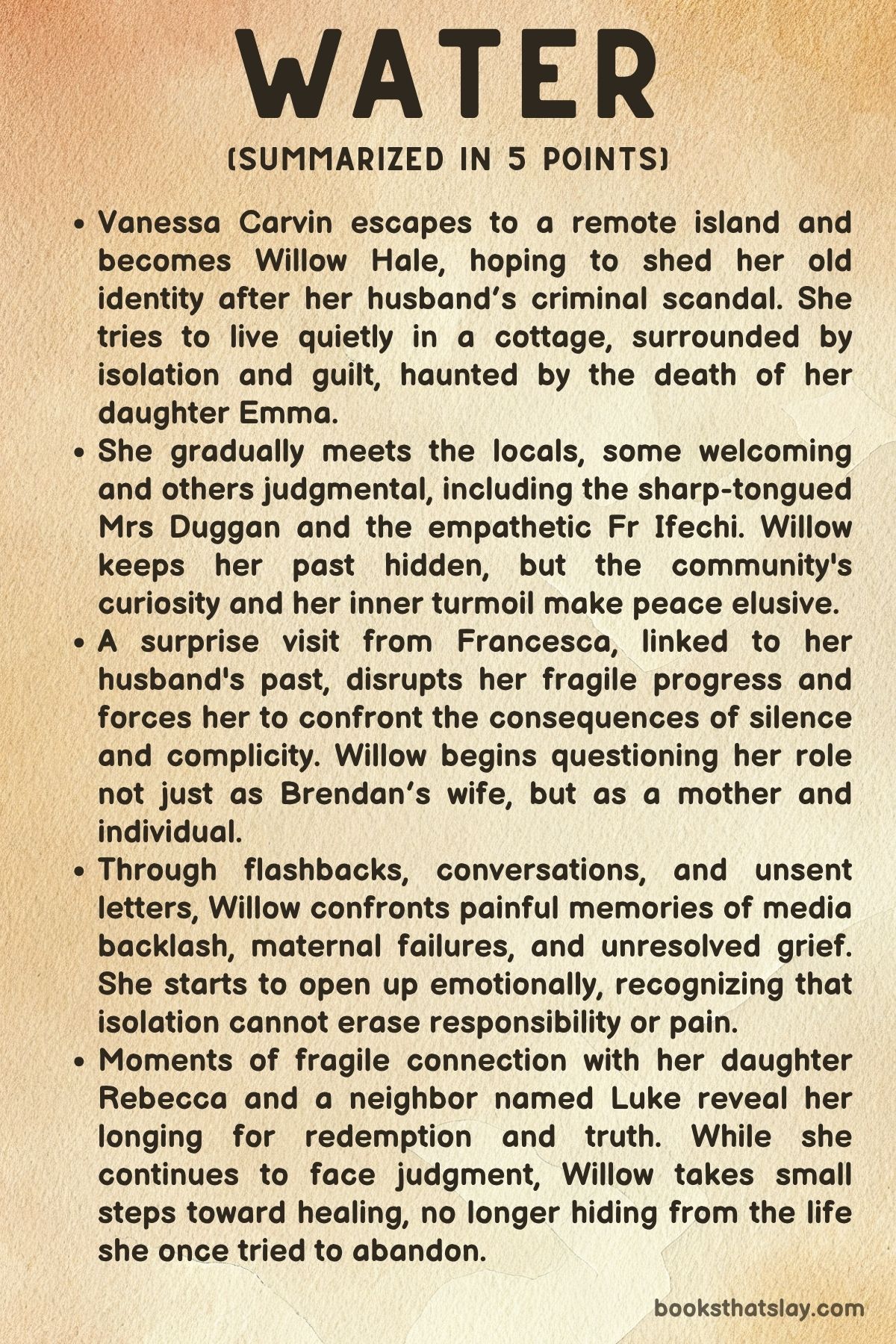

Water by John Boyne is a quietly powerful novella centered on Vanessa Carvin, a woman seeking anonymity and peace on a remote Irish island after her life is shattered by her husband’s crimes and the loss of her daughter. Renaming herself Willow Hale, she escapes into exile, hoping to find a kind of moral and emotional absolution.

The story explores the psychological aftershocks of public disgrace, maternal guilt, and emotional complicity. It also reflects on the subtle but potent forces of community, faith, and memory.

It is a profound, character-driven narrative about confronting truth, silence, and the search for personal integrity.

Summary

Vanessa Carvin arrives on a secluded Irish island under the name Willow Hale, abandoning her former life tainted by scandal and grief. Her husband, Brendan Carvin, a once-respected public figure in Irish swimming, has been disgraced for sexual misconduct.

Though she was never charged with wrongdoing, the public and personal fallout leaves her emotionally ravaged. Compounded by the loss of her elder daughter, Emma, and her fraught relationship with her surviving daughter, Rebecca, she seeks refuge in solitude.

She rents a modest cottage and disconnects from the internet, hoping to disappear into obscurity. Her only real company is a stray cat she names Bananas.

Her interactions with the islanders begin cautiously. The community, while initially wary, is drawn to her mysterious presence.

Some assume she’s a writer, and she doesn’t correct them. She connects, tentatively, with Fr Ifechi Onkin, the island’s Nigerian priest, who becomes one of the few individuals she confides in.

A woman named Mrs Duggan embodies the island’s narrow conservatism, frequently probing into Willow’s life. Her suspicions and prejudice represent the cultural rigidity that Willow must navigate.

Despite the friction, Willow finds some comfort in the simplicity of island routines. Her internal world, however, remains chaotic.

She reflects on her marriage, particularly Brendan’s authoritarian temperament and her struggle to balance motherhood with a growing awareness of his moral failings. Emma’s death—its circumstances unclear at first—looms heavily.

Her relationship with Rebecca remains strained, distant, and unresolved. Willow’s self-imposed exile is as much an escape as it is a confrontation with the silence she maintained during Brendan’s abuse of power.

The arrival of Francesca, one of Brendan’s accusers, shatters Willow’s fragile sense of control. Francesca’s presence is not coincidental; she demands acknowledgment of the past, especially of Willow’s perceived complicity.

Willow is forced to face the possibility that her silence, her need to preserve family appearances, may have contributed to others’ suffering. These interactions destabilize Willow further but also push her toward painful honesty.

Throughout the story, Willow experiences vivid flashbacks to Brendan’s trial and the media storm surrounding it. She remembers the accusatory gaze of society and the cruel interrogation she endured as a woman caught in the wreckage of her husband’s actions.

She finds a box of unsent letters to Emma and Rebecca—an intimate chronicle of her regrets, apologies, and unspoken love. These letters become symbols of her fractured motherhood and unexpressed grief.

As her time on the island continues, Willow attempts to participate in small acts of community—baking bread, visiting church. Each step is shadowed by guilt and ambivalence.

A stormy night brings her into closer connection with Luke Duggan, Mrs Duggan’s son. Their intimacy is brief, not romantic salvation but a moment of emotional recognition between two lonely people.

Contact from Rebecca, though fraught, signals a shift. Their exchange is tentative, filled with blame and unresolved pain, but it represents Willow’s desire to rebuild what little she can.

Eventually, she confronts Francesca directly, choosing to listen rather than defend herself. This is a turning point—her first genuine act of accountability.

In the final chapter, Willow walks along the beach at sunrise. She reflects not with certainty or closure, but with a quiet readiness to begin telling her own story.

She decides to send one of the letters to Rebecca and begins outlining a book. Her isolation is no longer a punishment, but a space for renewal.

While the past cannot be undone, Willow takes a fragile step toward reclaiming agency, identity, and the possibility of a future no longer shaped solely by grief and disgrace.

Characters

Willow Hale / Vanessa Carvin

Willow, once known as Vanessa Carvin, is the emotional nucleus of the novel. She is a woman undone by public disgrace, familial tragedy, and internalized guilt.

Her journey to the remote Irish island is not just an escape but a deliberate act of self-erasure and rebirth. In choosing the name “Willow Hale,” shaving her head, and cutting off contact with most people, she attempts to shed the skin of her former identity.

She seeks distance from the shame of being Brendan Carvin’s wife—a disgraced sports figure involved in a sexual abuse scandal. Willow is steeped in grief, primarily over the death of her elder daughter Emma, and the estrangement from her surviving daughter, Rebecca.

This maternal anguish haunts her solitude and fuels a deep need for atonement. Despite her desire for isolation, Willow’s interactions with islanders gradually compel her to reengage with humanity.

Her relationship with Luke Duggan reveals both her yearning for connection and the burdens she carries—emotional, societal, and sexual. The guilt of not acting decisively against her husband’s crimes and the public scorn she has endured blend into a singular portrait of a woman on the precipice of personal reckoning.

Her eventual turn to writing and sending letters marks the beginning of a subtle but profound transformation. It is not a story of redemption but of self-ownership.

Brendan Carvin

Though absent in the present timeline, Brendan’s shadow looms over the entire novel. A celebrated figure in Irish swimming, Brendan is later exposed as a serial abuser.

His downfall becomes a national spectacle. Through Willow’s reflections and conversations with others, Brendan emerges as a symbol of patriarchal abuse—charming, successful, and protected for far too long.

He is portrayed as a man obsessed with control. His refusal to have more children, his emotional detachment, and his domineering presence in the family highlight how his crimes were facilitated by silence and social deference.

Willow’s ambivalence—lingering love, loathing, disbelief—captures the complexity of being close to someone capable of monstrous acts. Brendan’s legacy is systemic, not merely personal.

He demonstrates how structures of power and fame shield predation and silence victims. His presence is the engine of much of Willow’s internal conflict.

Emma Carvin

Emma, Willow’s deceased daughter, is a spectral presence throughout Water. Though she does not appear directly, Emma is central to Willow’s unraveling.

Calm, sweet, and seemingly well-adjusted, Emma contrasts with her sister Rebecca. She was the emotional anchor in Willow’s memory.

The circumstances of Emma’s death are suggested to be suicide—possibly linked to Brendan’s abuse or the family’s collapse. This unresolved trauma festers in Willow, who tortures herself with questions about what she missed or chose not to see.

Emma’s absence leaves a void that shapes every decision Willow makes. From her retreat to the island to her hesitant attempts at communication with Rebecca, Emma’s death looms large.

Emma’s presence in the letters Willow never sent reveals emotional intimacy that was never properly expressed in life. It underscores themes of silence, distance, and irreversible loss.

Rebecca Carvin

Rebecca, the surviving daughter, is a deeply wounded figure. Her bitterness and anger toward Willow stem from long-standing emotional neglect.

Described as difficult from childhood, Rebecca clashed with her parents more openly than Emma. She now bears the scars of both familial betrayal and personal loss.

Her intermittent online contact with Willow is cold and angry. It reflects her inability to forgive the emotional abandonment and perceived complicity of her mother during Brendan’s scandal.

Rebecca expresses resentment not just for Brendan’s actions, but for Willow’s silence and inaction. She embodies a generation caught in the emotional crossfire of parental failure and public shame.

Her character forces Willow to confront the consequences of denial. Rebecca’s unresolved grief and fury highlight the long tail of trauma across generations.

Fr Ifechi Onkin

Fr Ifechi serves as both confessor and conscience for Willow. A Nigerian priest on the isolated island, he is himself an outsider.

Despite this, he possesses a moral clarity that contrasts with the evasiveness of the islanders. His role is not to absolve Willow but to challenge her to confront painful truths.

He listens without condemnation but does not let her escape accountability. Their emotionally raw conversations help Willow explore her own complicity.

Fr Ifechi also represents a more compassionate, introspective form of faith. He counters Willow’s growing disillusionment with institutional religion.

He offers a vision of spiritual responsibility rooted in empathy. His presence is vital in Willow’s moral awakening.

Mrs Duggan

Mrs Duggan is crusty, opinionated, and often antagonistic. She initially serves as a comic foil and social adversary to Willow.

Her suspicion, rudeness, and casual bigotry reflect the conservatism of the community. She disapproves of Willow’s presence and interrogates her motives.

She embodies the gossip-driven culture that ostracizes outsiders. Yet beneath her bluster, Duggan shows vulnerability and complexity.

Her opposition to the previous gay tenants and her obsession with the cat Bananas form a portrait of a woman trapped in a rigid social order. She indirectly forces Willow to assert herself.

Ironically, she contributes to Willow’s slow reclamation of personal strength. Duggan’s character showcases how social norms can both oppress and provoke resistance.

Francesca

Francesca, one of Brendan’s accusers, returns to Willow’s life with devastating force. Her arrival shatters Willow’s illusion of refuge on the island.

Francesca is articulate and composed. Her confrontation is raw and demands that Willow acknowledge her role—not in the abuse, but in enabling silence.

Willow does not defend herself. She listens, grieves, and absorbs the long-overdue condemnation.

Francesca represents the voice of survivors long denied justice or validation. Her presence drives Willow toward moral and emotional awakening.

She forces Willow to stop hiding behind shame. Through Francesca, the novel demands accountability and truth.

Luke Duggan

Luke, son of Mrs Duggan, offers unexpected tenderness. He represents a rare moment of emotional honesty in Willow’s life.

Younger and emotionally open, Luke provides a fleeting sense of connection. Their sexual encounter is rooted more in vulnerability than desire.

Both seek solace from personal pain. Luke is shaped by loneliness but does not judge Willow.

Their relationship is temporary, but illuminating. Through Luke, Willow glimpses what it means to be seen without shame.

He helps her rediscover her capacity for care and connection. His kindness subtly shifts her sense of worth.

Themes

Identity and Reinvention

The novel’s central exploration of identity is embodied in Vanessa Carvin’s transformation into Willow Hale. Her relocation to a remote island is not just geographical but existential.

She sheds her former name, shaves her head, and attempts to construct a life entirely removed from her history. This reinvention is not aspirational but defensive, an act of desperation to survive the emotional wreckage left behind by her husband Brendan’s public disgrace and her daughter Emma’s tragic death.

Yet, the act of renaming herself and withdrawing into obscurity is not without contradiction. While Willow wants to escape judgment, she still seeks validation, which emerges in her cautious interactions with the islanders, especially with Fr Ifechi and Luke Duggan.

The process of becoming Willow is not complete because Vanessa’s past—both her complicity and her pain—lingers in her psyche, disrupting her efforts to rebuild herself. Reinvention here is not a blank slate but a form of negotiation between what was and what could still be salvaged.

As the chapters progress, Willow is forced to confront the limitations of self-reinvention. Even in the absence of digital connectivity and social media, memory, guilt, and shame persist.

Her encounter with Francesca and her attempts to reconnect with Rebecca reveal that a new name cannot erase old wounds. The act of writing in the final chapters signals a shift—not toward erasing her identity but embracing it on new terms.

Reinvention becomes not escape but reckoning. It is a slow, reluctant acceptance that self-transformation only begins when the past is faced head-on.

Guilt, Silence, and Complicity

Throughout the novel, Willow is consumed by a slow-burning guilt that is both personal and systemic. Her sense of complicity in Brendan’s crimes is not just born from action, but from inaction—from silence, denial, and self-preservation.

This is one of the most emotionally complex aspects of her character. She is not portrayed as an outright villain or hero but as someone caught in the middle, too overwhelmed to act, too conditioned by privilege and dependence to challenge Brendan’s authority.

The guilt she carries is manifold: as a mother, as a wife, and as a woman who may have protected a predator, even inadvertently. Her conversations with Fr Ifechi, who gently but insistently asks her to examine her silence, act as a moral mirror.

They force her to reconsider whether her silence was ignorance or a willful blindness designed to keep the family’s image intact. The narrative does not excuse her but allows space for introspection.

Importantly, the guilt is not only moral but emotional. She feels she failed Emma and Rebecca not just by staying with Brendan but by emotionally withdrawing, prioritizing avoidance over confrontation.

The letters she wrote but never sent amplify this theme. They are confessions buried beneath years of emotional paralysis.

Willow’s eventual confrontation with Francesca is a turning point. By listening without defending herself, Willow accepts that complicity does not always require malicious intent.

It often flourishes through passivity. Her journey shows that silence, even when born from fear, has consequences, and acknowledging that is the first step toward moral accountability.

Motherhood and Emotional Distance

Motherhood in Water is presented as a fraught, painful experience rather than a sentimentalized ideal. Willow’s memories of her daughters—Emma and Rebecca—are steeped in regret, self-doubt, and sorrow.

She admits she was never a natural mother, and this frankness sets the tone for one of the novel’s most human themes: the gap between maternal expectation and emotional capacity. With Emma, she experienced a relative ease, but Rebecca was more challenging.

Her distance from both girls only grew as the dysfunction in her marriage increased. Her parenting was not abusive or neglectful in a traditional sense, but rather emotionally insufficient.

The trauma of Emma’s death—a tragedy implied to be suicide—haunts her. Not only as a loss but as a failure she believes she could have prevented if she had been more present, more assertive, more attuned.

The letters she wrote over the years, never sent, capture a deep maternal longing clashing with a persistent inability to express love effectively. Her relationship with Rebecca is especially revealing of intergenerational trauma.

Rebecca’s bitterness and anger stem not just from Brendan’s crimes but from Willow’s perceived loyalty to him. From her failure to act.

The conversation between them late in the novel is restrained yet charged. It is full of the things said and unsaid between mothers and daughters when pain goes unacknowledged.

Willow’s mothering is shown to be complicated, fallible, and raw. This makes her struggle with guilt and forgiveness all the more poignant.

This theme redefines motherhood not through nurturing perfection but through its emotional failures and the painful attempts to make amends.

Public Shame and Female Scapegoating

One of the novel’s most powerful thematic strands is the public treatment of women connected to powerful men accused of wrongdoing. Willow becomes a vessel for society’s displaced anger.

She is scorned not only as Brendan’s wife but as someone who is expected to have known, stopped, or punished him on behalf of his victims. The media’s treatment of her during Brendan’s trial is described as intrusive and dehumanizing.

She is asked humiliating questions while the real perpetrator stood relatively shielded. This gendered scapegoating is presented not as an anomaly but as a systemic reflex.

The woman’s proximity to male power is seen as complicity regardless of evidence. Willow is not innocent, but the depth of the judgment she faces is disproportionate to her proven involvement.

Moreover, her attempt to disappear only intensifies the scrutiny. On the island, rumors fill the vacuum of her silence.

Mrs Duggan and others make assumptions about her. This reminds readers how female identity, particularly when shrouded in mystery, is often constructed by others.

The novel questions why society needs a female figure to punish in the wake of male abuse. It shows how this serves a cathartic yet unjust function.

Francesca’s confrontation with Willow further illustrates this dynamic. Though Francesca is justified in her anger, the conversation shows how blame gets layered and displaced.

Particularly onto women who failed to challenge patriarchy when they had the chance. Willow’s journey becomes a broader commentary on how public shame is weaponized against women who are both victims and enablers, often simultaneously.

Memory, Trauma, and the Body

Trauma in Water is rendered as something not only psychological but physical. It is lodged in the body and daily habits of its characters.

Willow’s shaving of her head, her solitude, her reluctance to speak—these are all bodily responses to emotional pain. The island becomes a physical space where memory confronts her at every turn.

Her flashbacks are not chronological but fragmented, as memory often is when shaped by trauma. She remembers moments not in order but in intensity.

Emma’s death, Brendan’s trial, her own courtroom degradation. The novel underscores how trauma refuses narrative clarity.

It recurs in images, feelings, and regrets. The discovery of the unsent letters is a physical metaphor.

Grief and guilt stored in boxes, never released. Similarly, the act of swimming nude in the sea and later sleeping with Luke Duggan are not just plot developments but thematic assertions.

Willow’s body becomes a site of conflict between shame and healing. Her interactions with Luke are tender yet filled with uncertainty.

They show how trauma disrupts the ability to trust intimacy. The sexual encounter is not romanticized but observed as a moment where two wounded people seek brief comfort.

By the end of the novel, when she walks to the beach and considers sending a letter, Willow’s body finally begins to reclaim space. Not through bold gestures but through quiet assertion.

Trauma remains, but it no longer controls her entirely. Memory may haunt, but it now coexists with the possibility of movement and choice.