We Are All Good People Here Summary, Characters and Themes

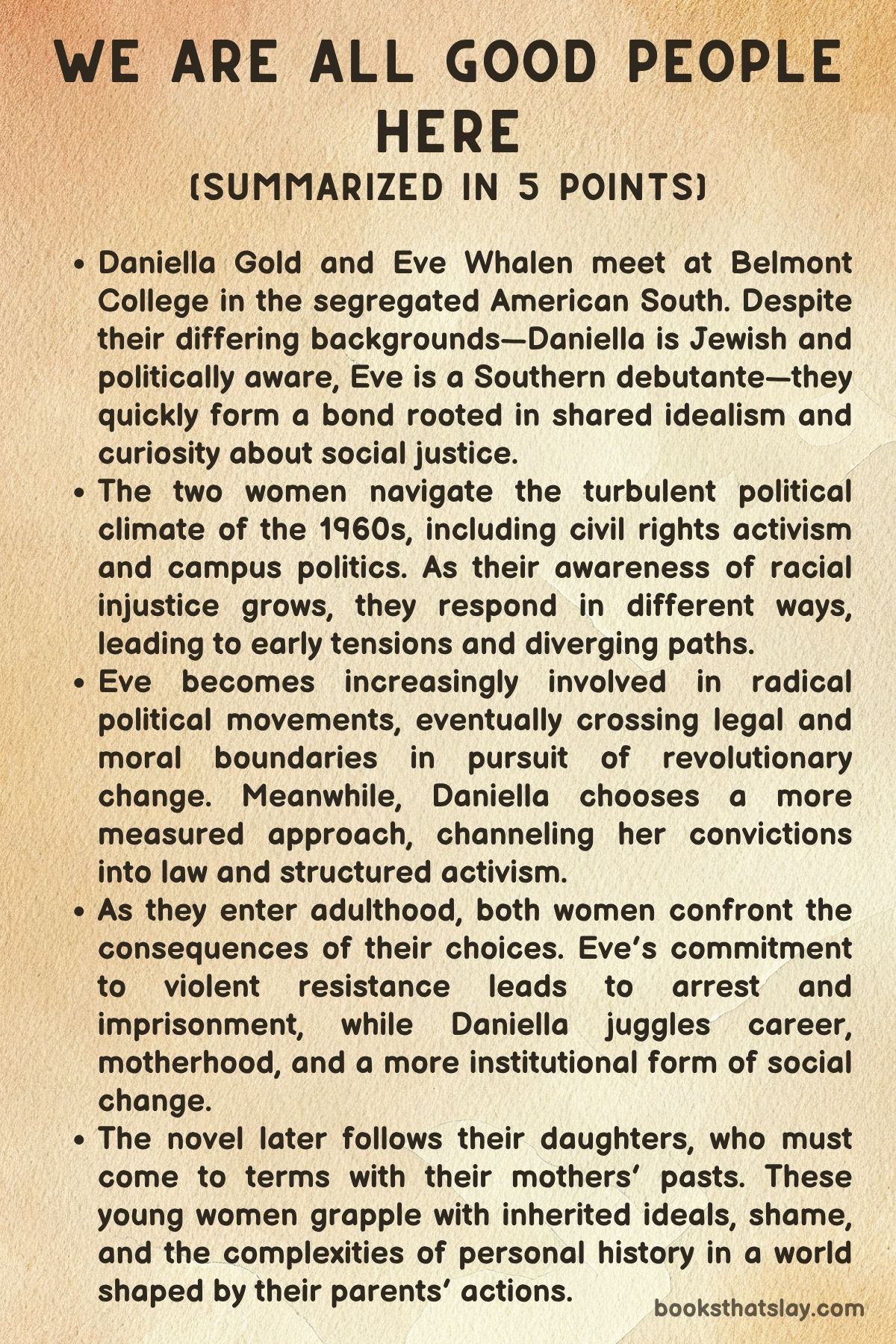

We Are All Good People Here by Susan Rebecca White is a moving and reflective novel that explores the personal conviction and social change across three tumultuous decades in American history.

Set against the backdrop of the 1960s civil rights movement and the cultural revolutions that followed, the story centers on two women, Daniella Gold and Eve Whalen, whose friendship begins in college and evolves through ideological rifts, political activism, and motherhood.

With nuance and emotional depth, White examines how youthful idealism can fracture under the weight of complex realities, and how past choices echo into the lives of the next generation.

This is a novel about privilege, protest, and the enduring tension between reform and revolution.

Summary

Daniella Gold and Eve Whalen meet as first-year students at Belmont College, a conservative Southern women’s school in the early 1960s. Daniella is a sharp and independent half-Jewish girl from Washington, D.C., while Eve is a wealthy and charismatic Southern Christian debutante from Atlanta.

Despite their cultural differences, the two quickly bond over their shared disillusionment with the complacency and prejudice around them. They begin to question the institution’s racial policies, especially after the mistreatment and eventual dismissal of Miss Eugenia, their Black maid, following Eve’s protest.

This early experience shakes their understanding of justice and privilege. As social life at Belmont intensifies, Eve receives a bid from the elite Fleur sorority, while Daniella is cut without explanation.

Eve suspects anti-Semitism and resigns in protest, despite pressure from her family. Both girls transfer to Barnard College in New York to find a more progressive environment.

Daniella adapts well and starts a relationship with Pete, a moderate Republican. Eve, feeling alienated, finds herself drawn to Warren, a radical activist.

The assassination of President Kennedy casts a somber tone over their transition into adulthood. In 1964, Daniella and Eve attend a CORE meeting and learn about the Freedom Summer project aimed at registering Black voters in Mississippi.

Eve is eager to join but is not accepted. Daniella, despite her fears, is chosen and travels South, where she experiences the brutal realities of racism.

Through letters, she communicates the danger and emotional toll of her activism. Her relationship with Pete deteriorates, and her friendship with Eve is strained as she accuses Eve of treating activism as a stage for her own identity struggles.

The murder of civil rights workers Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner deepens Daniella’s political awareness and resolve. By the late 1960s, Eve becomes involved in radical politics, aligning herself with the Weather Underground.

Fueled by frustration and a desire for more direct action, she and Warren rob a bank to fund their cause, resulting in the death of a security guard. Eve goes underground and cuts ties with her former life.

Meanwhile, Daniella is in law school, married to Pete, and raising a daughter, Sarah. She’s shocked when she learns of Eve’s arrest for the robbery.

The news forces her to reflect on how their paths have diverged and where the boundary lies between justice and extremism. Eve is convicted and sent to prison.

She refuses to mount a traditional legal defense and instead embraces her punishment as a political statement. Incarcerated, she begins to reevaluate her past, including her relationship with Warren and the life she abandoned.

Daniella, now a successful civil rights attorney, continues her work within the system she once criticized. Years later, the two women meet again.

Their reunion is strained but necessary. They confront their choices and the consequences of their ideals.

Daniella challenges Eve’s past violence, while Eve questions Daniella’s compromises. Despite tension, their connection remains, altered but not broken.

In the final chapter, the focus shifts to their daughters. Sarah, Daniella’s child, learns about Eve’s radical history and is disturbed by what she finds.

Harmony, Eve’s daughter, struggles with the legacy of her mother’s past and the emotional distance in their relationship. Both young women are left to make sense of the moral and political complexities their mothers wrestled with.

The novel ends with an acknowledgment of how the idealism of one generation shapes—and burdens—the next. The story suggests that the pursuit of justice is never simple or finished.

Characters

Eve Whalen

Eve begins the novel as a privileged Southern debutante who seeks to distance herself from the conservative values she was raised with. Her character arc is one of radical transformation, driven by a need to rebel against the hypocrisy and injustice she witnesses.

Initially well-intentioned, Eve’s actions often reflect a youthful arrogance and impulsiveness. She is idealistic, passionate, and reckless.

Her transition from a college student protesting social injustices to a member of a violent revolutionary group underscores the novel’s examination of how ideological fervor can tip into extremism. Eve’s radicalization is partly born from frustration at being sidelined in formal activism and from guilt over her early failures, such as Miss Eugenia’s firing.

Her later involvement in a deadly bank robbery demonstrates the tragic culmination of her unchecked ideology. However, prison forces introspection, and in middle age, Eve appears chastened and subdued.

She remains haunted by her past but chooses not to vocalize remorse publicly, which speaks to her stubbornness and continued resistance to conventional narratives of guilt and redemption. Her relationship with her daughter Harmony is distant and strained, marked by secrecy and the burden of inherited trauma.

Daniella Gold

Daniella serves as the novel’s moral compass. As a half-Jewish, Northern transplant at a Southern college, she brings a critical outsider’s perspective.

From the start, she is more measured and introspective than Eve, with a deeply rooted sense of justice that doesn’t veer into zealotry. Her activism is deliberate and grounded, as shown in her decision to join Freedom Summer despite the risks.

While Eve seeks attention and validation, Daniella is more concerned with actual impact. Her experiences in Mississippi mature her political awareness.

Though she initially breaks off her relationship with Pete due to ideological differences, she eventually marries him, suggesting a nuanced compromise between her idealism and the demands of adult life. As a civil rights lawyer and mother, Daniella becomes someone who channels her convictions into systemic change.

Her reunion with Eve in middle age is telling. Daniella challenges Eve on her past, insisting on accountability, yet she does not reject her entirely.

Her approach to activism is characterized by moral consistency and emotional intelligence. She raises her daughter, Sarah, to value truth and justice, though she too must confront the complexities of legacy when Sarah uncovers Eve’s past.

Warren

Warren is a charismatic and intense figure who represents the seductive pull of radicalism. Introduced as a magnetic activist in New York, he becomes Eve’s partner in both ideology and romance.

His radical politics and embrace of militant tactics play a key role in Eve’s transformation. While passionate about dismantling systemic oppression, Warren lacks the moral restraint that defines Daniella.

He is more interested in symbolic gestures of revolution than in practical or sustainable change. His character does not evolve significantly.

Instead, he serves as a catalyst for Eve’s descent into extremism. After their criminal act and Eve’s imprisonment, Warren’s presence fades, symbolizing the transience and destructiveness of such radical ideologies when detached from responsibility and ethical reflection.

Pete

Pete, initially presented as Daniella’s moderate Republican boyfriend, functions as a foil to both Daniella and Eve. His character undergoes a quiet evolution.

Although his early political views seem incompatible with Daniella’s activism, he grows to support her ambitions and becomes her husband. His presence in the narrative highlights the potential for ideological flexibility and compromise within personal relationships.

Pete is not deeply involved in the political movements of the time, but he represents a form of stability and personal loyalty. His arc reflects the novel’s theme of how individuals navigate complex moral and political terrain without necessarily becoming revolutionaries themselves.

Miss Eugenia

Although a minor character in terms of page time, Miss Eugenia’s role is pivotal. Her unjust firing at the beginning of the novel is a catalyst for both Eve and Daniella’s political awakening.

She symbolizes the systemic racism and everyday injustices that the young women are initially blind to. Her presence in the story serves as a moral benchmark.

Her silent endurance contrasts with Eve’s performative outrage and Daniella’s quieter resolve. She is never given a large voice, emphasizing the marginalization of Black women even within supposedly progressive narratives, which is one of the novel’s subtle critiques.

Sarah and Harmony

Sarah, Daniella’s daughter, and Harmony, Eve’s daughter, appear primarily in the final chapter. They represent the next generation grappling with their mothers’ legacies.

Sarah is principled and idealistic, shaped by Daniella’s moral clarity. Harmony is more conflicted, burdened by the shadow of Eve’s criminal past.

Their reactions to their mothers’ choices illuminate the novel’s central questions. How do we pass on values, how do we reconcile past mistakes, and what does justice look like across generations?

Sarah seeks transparency and accountability. Harmony struggles with inherited guilt and the distance in her relationship with Eve.

Their characters suggest that the future may hold the possibility for healing, but only if the truth is fully confronted.

Themes

Identity and Privilege

The novel presents identity and privilege as complex, layered, and often invisible forces that shape each character’s experience and worldview. Eve and Daniella begin as college roommates from vastly different backgrounds—Eve, a wealthy Southern Christian debutante, and Daniella, a middle-class, half-Jewish girl from Washington, D.C.

Their budding friendship serves as a microcosm of larger societal divisions, and their awareness of privilege begins with small awakenings, like the firing of Miss Eugenia due to Eve’s naive protest. Throughout the novel, Eve wrestles with her own privilege, often attempting to reject or compensate for it through increasingly radical activism, culminating in her involvement in a violent bank robbery.

Her trajectory demonstrates how unchecked guilt and anger, when coupled with privilege and a desire to “fix” things, can lead to moral distortion. Daniella, on the other hand, navigates her identity with more caution and introspection.

Her Jewish heritage and outsider status at Belmont make her attuned to exclusion and discrimination, and this awareness later manifests in a more grounded, systemic approach to justice through law and civil rights work. The contrast between the two women illustrates how privilege is not only a matter of wealth or race but also of how individuals choose to respond to their social positioning.

The novel never offers simple conclusions but instead invites readers to consider how identity and privilege influence decisions, relationships, and the capacity for moral clarity.

Activism and Moral Complexity

Activism is a central theme that evolves in layered and morally ambiguous ways throughout the story. Initially, both Eve and Daniella are drawn to social justice through their exposure to racism and inequality at Belmont.

Their early efforts—writing protest letters, joining CORE—are rooted in idealism and youthful passion. However, their paths diverge sharply as Eve becomes increasingly disillusioned with institutional change and turns to revolutionary methods.

Her decision to join the Weather Underground and participate in a violent bank robbery is portrayed not as a triumph of conviction but as a descent into extremism. The novel presents her radicalism as both a response to real injustice and a form of escapism or emotional compensation for her Southern guilt.

Daniella, by contrast, chooses to engage with activism through the legal system. Her decision to become a civil rights lawyer reflects a belief in the possibility of gradual, principled change, despite the frustrations of bureaucracy and compromise.

The novel challenges the romanticization of protest, especially when it borders on violence, and explores the emotional toll of long-term activism. It questions whether ends justify means and suggests that moral certainty can be dangerous when divorced from empathy and reflection.

Through its two protagonists, the novel maps a spectrum of activist responses and emphasizes the internal conflicts that often accompany the pursuit of justice. Activism, here, is not a monolithic force but a deeply personal, often painful journey shaped by time, experience, and evolving values.

Friendship and Estrangement

At the heart of the novel is the complex, often fraught friendship between Eve and Daniella. Their bond begins with mutual fascination and support, forged in the intimate setting of a Southern women’s college.

Initially, they share dreams, secrets, and a desire to challenge the norms they see around them. However, as the story progresses, their friendship becomes strained under the weight of ideological differences, life choices, and unspoken resentments.

Daniella’s cautious, reflective nature contrasts with Eve’s impulsiveness and desire for dramatic change, leading to moments of misunderstanding and betrayal. Particularly when Eve is rejected from the Freedom Summer project and feels sidelined by Daniella’s involvement.

Their eventual estrangement underscores how political and personal paths can diverge even among those who start with shared values. When they reunite decades later, their conversation is marked by both warmth and wariness.

They revisit old wounds, question each other’s decisions, and struggle to reconcile the idealistic girls they once were with the women they have become. Yet, despite the distance, their bond endures in a muted but meaningful way.

Their story is a poignant reflection on how friendships can survive disappointment. How people grow apart through choices rather than malice, and how reconciliation does not always mean resolution.

The novel presents friendship not as an unbreakable constant but as a living relationship that evolves with each person’s journey. Sometimes sustaining, sometimes straining under the weight of time, ideology, and experience.

Generational Legacy and Inheritance

One of the most powerful arcs in the novel is the exploration of how one generation’s choices shape the consciousness and lives of the next. In the final chapter, the narrative shifts to focus on the daughters of Eve and Daniella—Harmony and Sarah—who must grapple with the legacies left to them.

These legacies are not material, but moral and emotional. Harmony struggles with her mother’s past involvement in a violent crime, feeling the shame and confusion of having a parent whose actions were once radical and now appear incomprehensible.

Eve’s silence and guilt create a wall between her and Harmony. One that reflects the difficulty of passing down values without confronting hard truths.

Sarah, raised by Daniella in a more stable and morally consistent environment, also experiences discomfort as she learns more about the complexities of her mother’s youth. The novel suggests that children do not inherit ideology, but they inherit the emotional fallout and moral residues of their parents’ choices.

This theme is especially resonant in the context of the late 20th century. As America begins to look back on the civil rights and counterculture movements with a mixture of pride, regret, and confusion.

The daughters’ responses—conflicted, questioning, at times resentful—highlight how difficult it is to reconcile youthful idealism with adult responsibilities. Through them, the novel explores the long shadows cast by activism.

The burden of unspoken histories, and the enduring question of how to honor the past while forging a future.