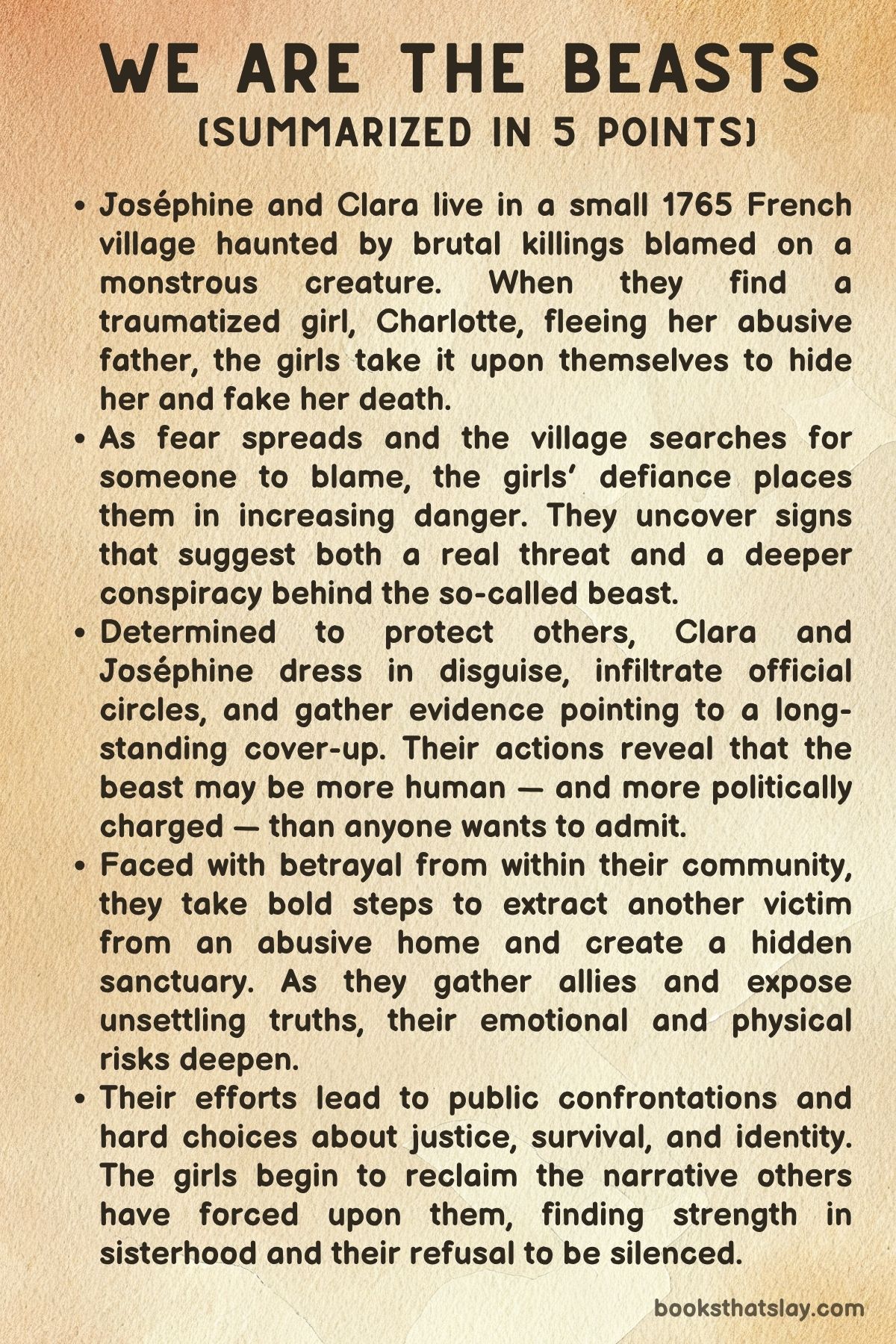

We Are the Beasts Summary, Characters and Themes

We Are the Beasts by Gigi Griffis is a historical novel set in 18th-century Gévaudan, France, blending raw survivalism with an unflinching look at trauma, abuse, and the bonds forged through resistance. The book follows Joséphine, a teenage shepherdess, as she fights to protect the people she loves from the threat of a mysterious beast—and from the far more horrifying violence inflicted by the men around her.

With haunting atmosphere and intimate character exploration, the novel reframes monstrousness as something both literal and human, asking who the real beasts are in a society that punishes the innocent and silences the wounded. It is a story of women and girls refusing to stay broken.

Summary

The story begins with a moment of peril that sets the tone for everything that follows. Joséphine, a young shepherdess, climbs down a rocky cliff to save a stranded lamb, risking her life despite her intense fear of heights.

This single act reflects the depth of her commitment to those she loves—Clara, her tender and brave companion, her grandmother Mémé, and their animals, which are as essential to their livelihood as food or shelter. In rural 18th-century Gévaudan, survival is brutal and love is often an act of sheer defiance.

But danger in this world is not limited to starvation or jagged cliffs. A creature known as the Beast of Gévaudan stalks the region, killing with violence so grotesque it inspires myth.

When Joséphine and Clara discover the mutilated body of a boy, Pascal, they suspect the Beast has struck again. But hidden nearby is Charlotte, a young girl who witnessed the killing—and knows it was no monster, but her own father who committed the crime.

He returned to further disfigure the corpse, hoping to disguise his cruelty as the Beast’s work. This revelation shatters the safety Joséphine and Clara have tried to maintain.

Rather than surrender the child to the same abuses she fled, Joséphine and Clara stage Charlotte’s death, crafting a deception that allows them to hide her. This decision binds them even closer together, linking their survival to Charlotte’s.

Joséphine, still carrying the scars of having been abandoned during a plague, channels her fear into purpose. She will not let another child be left to fend alone in a brutal world.

The village accepts the story of Charlotte’s death. When her older sister Hélène brings her bloodied dress to the square, the villagers erupt in fear and superstition.

A predatory priest riles them into blaming women and girls for the Beast’s wrath. The atmosphere grows more oppressive as collective paranoia targets those least capable of defending themselves.

Yet, in the quiet corners of their world, women resist. Mémé welcomes Hélène into her home, unaware of the lies circling around her.

Joséphine and Clara consider placing Hélène in the only place her father won’t look—the abandoned, half-collapsed home from Joséphine’s own childhood, a site heavy with personal loss and dread.

Meanwhile, the psychological burden of their deception weighs heavily on the girls. Hélène, grieving a sister she believes dead, is brought to their home by Mémé.

Charlotte must be hidden in the rafters. The emotional toll is sharp as she listens to her sister mourn her, unable to speak or reveal the truth.

Even so, Mémé eventually learns what they’ve done and supports them fully. This solidarity among women becomes a lifeline against a society that refuses to protect them.

The arrival of soldiers in the village signals more instability. Led by Lafont, Joséphine’s former foster father, the troops are more interested in theatrics and violence than real justice.

They dress sheep in stolen dresses to lure the Beast—a grotesque mixture of absurdity and cruelty. Claw marks on the barn confirm that a creature does exist, and it’s close.

Fear sharpens as the villagers look for someone to blame. Hélène, still under her father’s control, nearly reveals the truth before retreating in fear.

Another girl, Eugénie, quietly suggests that the real beast walks on two legs. Her own bruises testify to this.

Recognizing the scope of danger, Clara and Joséphine decide that Charlotte and Hélène are not the only ones who need saving. They begin plotting to rescue Eugénie as well.

But their plans are cut short when Hélène’s father finds their hidden refuge. In a scene charged with violence and desperation, Joséphine kills him in self-defense, aided by one of their sheep.

The moment is chaotic and intimate—bloody and necessary. What follows is damage control.

They bury the body, invent stories, and try to salvage safety from the wreckage.

Clara confesses her romantic love for Joséphine, and their relationship deepens beyond shared trauma. But even this is interrupted.

Louis, once Joséphine’s foster brother, arrives seeking answers. His love for Pascal is revealed, and in that grief, another alliance is born.

Joséphine and her circle of survivors now include him too. Their alliance becomes an informal family—bound not by blood, but by mutual loss and a need to protect one another from a hostile world.

Yet the body they buried vanishes. The Beast—real and physical—has claimed it.

The horror is not just symbolic anymore. The creature exists alongside the human monstrosity, doubling the threat.

In the novel’s climax, Joséphine ventures into the forest alone and finds herself face to face with the Beast. It is no mythic demon, but a lioness—likely once kept as an exotic pet and released into the wild.

The lioness is not evil but desperate, protecting her cubs just as Joséphine protects her own. This realization reframes everything.

The Beast is not otherworldly. It is motherhood, grief, survival.

It is also the priest, the fathers, the fear. Monsters are made and unleashed.

When the villagers, inflamed by the priest, come to kill Joséphine, she turns their narrative against them. She embraces the role of the witch, the Beast, the villain, if it means the others can escape.

Her performance terrifies the mob into hesitation. Eugénie appears with the lion cub, luring the lioness to attack.

Chaos explodes. Villagers are mauled.

Charlotte fights. Joséphine is injured.

In the end, the lioness retreats with her cub—wounded, but not slain.

With danger momentarily passed, the girls plan their escape. Belle, once complicit, redeems herself by helping them prepare.

Their departure is both literal and symbolic. They leave not just the village but the oppressive structures that shaped their lives.

The final scenes echo with pain and promise.

In the epilogue, a journalist arrives in Gévaudan searching for the truth. The legend of the Beast has outlived the facts.

The testimonies he gathers contradict one another. Some say the Beast was a lion.

Others say it was a girl, or many girls. The myth has become a mirror.

The real monsters were never just the ones in the woods, but the ones who refused to believe women, the ones who feared disobedient girls. Joséphine and her sisters have disappeared into history—but they have rewritten it in the process.

They are the Beasts now, and they survived.

Characters

Joséphine

Joséphine is the resolute and emotionally complex protagonist of We Are the Beasts, a young shepherdess marked by trauma, loss, and an unyielding drive to protect those she loves. Her character arc is steeped in resilience and sacrifice, beginning with her desperate efforts to rescue a lamb from a cliff—an act that not only signifies her courage but also foreshadows the lengths she will go to safeguard Clara, Mémé, and eventually Charlotte and Hélène.

Joséphine carries deep psychological scars from her childhood, particularly the abandonment she suffered during a plague, and these experiences have etched a permanent sense of dread and responsibility into her identity. Her instinct to act decisively—even recklessly—is not rooted in arrogance but in a deep-seated fear of failing those who depend on her.

As the story unfolds, Joséphine evolves from a traumatized survivor into a fierce guardian and rebel. She becomes the de facto leader of their small, makeshift family, shouldering unbearable burdens while fiercely clinging to her agency.

Her relationship with Clara anchors her emotionally, and it is through this romantic and spiritual bond that Joséphine begins to rediscover parts of herself lost to grief and fear. The climax of her development occurs when she confronts both literal and metaphorical beasts—facing down the lioness in the woods and the village mob with equal determination.

Her eventual self-identification with the “beast” becomes an act of reclamation; she turns the villagers’ fear into her strength, subverting their power through performance and myth. Ultimately, Joséphine’s journey is a testament to the brutal, redemptive power of love, sacrifice, and survival.

Clara

Clara is Joséphine’s companion, confidante, and eventually, her romantic partner—a source of gentle strength and steadfast loyalty throughout We Are the Beasts. She is portrayed as deeply empathetic, emotionally mature, and fiercely supportive, embodying a quieter but no less potent form of resistance.

Clara’s role within their small family is that of nurturer and rational thinker, often counterbalancing Joséphine’s more impulsive instincts with careful thought and emotional depth. Her affection for Joséphine is evident from the earliest scenes, and her ability to recognize Joséphine’s internal battles with trauma and guilt underscores her emotional intelligence.

Clara also bears the emotional fatigue of constant caregiving. Her confession of exhaustion reveals the hidden costs of compassion and responsibility, making her character deeply relatable.

She does not seek the spotlight nor the role of hero, yet her courage surfaces when it matters most—from sheltering Charlotte to plotting dangerous rescues. Her love for Joséphine grows into something transformative, culminating in a declaration that affirms not only her romantic devotion but also her place in this found family’s core.

Clara’s presence is a grounding force, reminding Joséphine—and the reader—that survival is not just about fighting monsters but about finding sanctuary in love and connection.

Mémé

Mémé is the moral compass and maternal figure in We Are the Beasts, a steadfast elder who represents both wisdom and quiet rebellion. She is the backbone of the household and the glue that holds the fragile ecosystem of care and protection together.

Unlike many adults in the village who are governed by fear, superstition, or malice, Mémé is guided by a sense of deep, unwavering justice. Her embrace of Charlotte and later Hélène—without judgment or hesitation—demonstrates her instinctual commitment to compassion, even at great personal risk.

Her character illustrates the intergenerational legacy of survival. Mémé has weathered life’s cruelties and emerges not embittered but more resolved to nurture those whom the world discards.

Her quiet strength and open-mindedness provide an emotional sanctuary for the girls, and her support is pivotal when the others begin to falter. When she learns the truth about Charlotte and Hélène’s father, her response is fierce and unambiguous, reinforcing the novel’s central theme of collective female resistance.

Mémé may not wield weapons or confront the beast directly, but her presence legitimizes and emboldens the younger generation’s fight for freedom and dignity.

Charlotte

Charlotte is both the symbol and spark of the narrative in We Are the Beasts, a traumatized child whose rescue catalyzes Joséphine and Clara’s transformation from survivors to protectors. Silent and fearful when first discovered, Charlotte’s presence quickly shifts the dynamic of the story.

She is no longer a passive victim but an embodiment of what must be preserved at all costs—innocence, safety, and the possibility of a future unmarred by violence. Her bond with Joséphine becomes central to the novel’s emotional tenor, with Joséphine projecting onto Charlotte her own lost childhood and vowing to do what no one did for her: protect without expecting gratitude or reciprocation.

Charlotte’s development is subtle but profound. Initially withdrawn, she begins to assert herself—most notably when she takes part in the final confrontation with the lioness.

Her act of stabbing the beast in the mouth is not just an act of survival but a symbolic gesture of reclaiming agency. Through Charlotte, the novel interrogates cycles of violence and questions whether innocence can survive in a world where monsters wear human faces.

Her bravery in the final moments reframes her not as someone who needed saving, but as someone who, in turn, saves.

Hélène

Hélène, Charlotte’s older sister, is one of the most complex and conflicted figures in We Are the Beasts. At first, she appears as an obstacle—devoted to the abusive father who tormented her, unable or unwilling to see the truth.

But her character arc is defined by gradual awakening and painful reckoning. Hélène’s internal conflict is shaped by denial, fear, and indoctrination; she has been both manipulated and brutalized, and her belief in her father’s goodness is not naive but protective—a psychological survival mechanism.

When she learns the truth and joins the other girls, Hélène begins a journey toward healing and self-assertion. Her love for Charlotte remains unwavering, and it is that bond that ultimately forces her to confront reality.

Hélène’s scream during her staged “abduction” marks a turning point—it is an exorcism of silence, a declaration of both pain and resistance. Though her transformation is not as fully realized as Joséphine’s or Clara’s, her willingness to break away from her father’s control and join the others underscores the novel’s central theme of collective liberation.

She represents the slow, difficult process of unlearning abuse and learning to trust again.

Eugénie

Eugénie is introduced later in the novel but quickly becomes a powerful figure in We Are the Beasts—a girl scarred physically and emotionally, yet undeterred by fear. Her injuries and veiled references to abuse hint at a backstory marked by violence, but she channels her pain into courageous, even reckless, action.

It is Eugénie who reappears at a critical moment with the lion cub, a calculated risk that brings the true beast into the fray and exposes the absurdity of the villagers’ myths. Her boldness is both shocking and inspiring, cementing her as a figure of disruption and transformation.

Eugénie’s role also deepens the story’s central metaphor: that monstrousness is often projected onto those who rebel against the norm. She is viewed with suspicion by the villagers but becomes a hero among the girls.

Her fate—being thrown by the lioness—underscores the high cost of resistance, yet her courage remains unshaken. Eugénie represents the fiery, untamed aspect of femininity that refuses to be cowed, a living testament to survival’s many faces.

Louis

Louis begins as comic relief in We Are the Beasts, a seemingly ineffectual man whose significance grows steadily as the story unfolds. His character arc is one of quiet, redemptive transformation.

Initially underestimated, Louis becomes a crucial ally, particularly when he reveals his relationship with Pascal and his own grief and vulnerability. Like the girls, Louis has been marked by pain and loss, and his decision to support them in hiding the body and crafting an alibi shows his willingness to defy societal expectations in favor of moral truth.

Louis is the only adult man in the novel who emerges as trustworthy and compassionate. His empathy, especially toward Eugénie and the girls, contrasts sharply with the violence and cowardice of other male figures.

In a world where men are often either predators or bystanders, Louis’s humanity offers a glimmer of possibility. His arc illustrates that healing is not exclusive to the young or the female; he is, in his own way, a survivor reclaiming purpose through solidarity.

The Lioness (The Beast)

The lioness, while non-human, is one of the most symbolically potent characters in We Are the Beasts. Initially cloaked in myth as the fearsome Beast of Gévaudan, the revelation that the monster is a real lioness reframes the entire narrative.

She is not a demon or curse but a displaced mother—hungry, cornered, and driven by primal instincts to protect her cub. This parallel with Joséphine is deliberate and poignant: both are “beasts” made dangerous by the need to defend their own.

The lioness represents the misunderstood feminine—ferocious, protective, and feared because she defies containment. Her ultimate retreat with her cub, rather than death at the hands of the villagers, subverts the traditional beast-slaying trope.

She survives, as do the girls, and her continued presence in the wilderness becomes a symbol of wildness and maternal strength that refuses to be tamed. In this way, the lioness is not merely a creature of terror, but a mirror held up to the human characters, particularly the women, who are also fighting for survival in a hostile world.

Themes

Survival and Protection as Moral Imperatives

In We Are the Beasts, survival is not merely an instinct but a moral imperative that shapes every decision Joséphine and her chosen family make. The environment is unforgiving, characterized by famine, feral animals, and constant threat of violence, both human and otherwise.

For Joséphine, each act of survival becomes entangled with the need to protect those she loves—Clara, Mémé, Charlotte, and later Hélène and Eugénie. Her fear of heights does not stop her from rescuing a lamb from a cliffside because the animals are part of their sustenance, and more deeply, because they are part of the circle of life she feels responsible for.

The same drive pushes her to lie, to fight, and eventually to kill. Yet, these actions never read as instinctual—they are always portrayed as conscious, agonizing decisions where physical preservation is inseparable from emotional and moral responsibility.

When she shelters Charlotte and later orchestrates Hélène’s escape, Joséphine is not simply acting as a protector but reclaiming agency for herself. Each rescue is a reckoning with her own abandonment, transforming trauma into purpose.

The refusal to accept that girls must fend for themselves is a moral stance as much as it is a survival tactic. Even Clara, who confesses to exhaustion from always being the caregiver, chooses to continue because she recognizes that their survival is interwoven with mutual protection.

The novel’s most powerful moments of heroism arise not from the defeat of external threats, but from the relentless pursuit of each other’s safety, even when it demands profound personal sacrifice.

Gendered Violence and the Myth of the Beast

The Beast of Gévaudan is a literal and symbolic force in the novel, functioning as a spectral presence that enables the village to project its anxieties, superstitions, and deep-seated misogyny. The murders of girls and children are immediately attributed to the Beast, but as Joséphine and Clara uncover, many of these atrocities are human-made.

The real beasts are fathers, priests, and soldiers—men who abuse their power under the cloak of piety, law, or legend. The story of Pascal’s death, initially believed to be the work of the Beast, is revealed to be a cover-up for domestic violence and paternal rage.

The priest’s sermons that blame women and girls for provoking the Beast reflect a society eager to scapegoat the vulnerable rather than confront the men who perpetrate harm. This gendered lens of violence is not just systemic but ritualized, using the myth to control and silence women.

When Joséphine later embodies the role of the Beast, she reclaims the narrative. Her performance of monstrosity is a form of subversion—turning society’s superstitions into a weapon to protect those it would otherwise destroy.

The lioness, a real animal who is also a mother and survivor, emerges as a mirror to Joséphine and the other girls. She is feared, not for her cruelty, but for her independence and strength.

By the end, the line between monster and martyr is blurred entirely. The myth of the Beast endures not as a tale of terror, but as a legend rewritten by the girls who refused to be its victims.

Chosen Family and Queer Kinship

Throughout We Are the Beasts, the concept of chosen family becomes the emotional core of the narrative. Joséphine and Clara’s bond is forged not only through shared hardship but through an unspoken, gradually affirmed love.

Their care for each other is not conditional on duty or obligation—it is a deeply felt recognition of each other’s pain, resilience, and worth. Clara’s confession of romantic love toward the end is not treated as revelation but as the natural culmination of years of quiet, fierce intimacy.

Similarly, Mémé functions as more than a grandmotherly figure—she becomes a moral anchor, guiding the girls through decisions that would otherwise overwhelm them. Her unwavering support, even when confronted with violence and deception, signifies the strength of bonds formed not by blood, but by mutual belief in each other.

The inclusion of Louis, Eugénie, Charlotte, and eventually Belle into their circle reinforces this theme. Each has been failed by traditional structures—patriarchy, religion, family—and finds solace in a group that operates according to a different ethic: one of solidarity, care, and trust.

This alternative kinship model is not without its tensions, as shown in the conflicts between Clara and Joséphine, but those disagreements are allowed space without jeopardizing the unity of the group. In their final departure, as they head south with their sheep, supplies, and love for each other, the girls create a living testament to survival not through isolation or individualism, but through the strength of community and chosen kin.

The Weaponization of Superstition and Religious Authority

Religion in We Are the Beasts is depicted not as a source of solace but as a tool of repression. The priest, as the village’s spiritual authority, exploits fear and superstition to maintain power and instill guilt, particularly in women and girls.

His sermons do not offer hope but assign blame, suggesting that the Beast’s attacks are divine punishment for feminine transgressions. The townspeople are conditioned to accept these claims, internalizing the idea that their suffering is a result of their own impurity.

This environment allows violence to proliferate unchecked, as men like Charlotte’s and Hélène’s father are shielded by patriarchal structures that refuse to scrutinize their actions. The absurdity of the soldiers dressing sheep in stolen clothes to lure the Beast reflects how superstition overrides logic, often at the expense of the powerless.

Joséphine’s decision to perform the role of the Beast—a witch-like figure who invokes thunder and commands fear—is a brilliant inversion of this mechanism. She understands that the only way to undermine the priest’s influence is to adopt the very imagery he wields against them.

Her performance dismantles his authority by reframing the symbols he uses to terrify into instruments of resistance. Eugénie’s appearance with the lion cub provides the ultimate disruption—replacing myth with reality, faith with fact, and fear with action.

In this world, religious authority is not merely ineffective; it is dangerous. The novel critiques how easily it can be harnessed to uphold violence and how power can be reclaimed by reclaiming the narrative itself.

The Transformative Power of Rage and Love

Joséphine’s emotional journey in We Are the Beasts is defined by a volatile mix of rage and love, both of which become tools for transformation rather than destruction. Her initial choices are fueled by anger—at the world that abandoned her, at the men who abuse with impunity, and at the apathy of those who look away.

But this rage is never directionless. It sharpens her purpose, galvanizes her resolve, and ultimately enables her to protect others where she was once left unprotected.

Her love for Clara, Mémé, and the girls she rescues is equally fierce. It is not soft or passive, but active, requiring hard choices, confrontation, and immense personal risk.

When Joséphine kills Charlotte’s father, it is an act of love no less than an act of rage. The story’s emotional resonance comes from this balance—rage does not consume her, and love does not weaken her.

Instead, each fuels the other, creating a dynamic form of resistance that is deeply personal and politically powerful. Charlotte’s hand in hers at the end is emblematic of this synthesis.

It is not a moment of peace, but of clarity: the battle is not over, but Joséphine now understands that her strength lies in how deeply she feels, how fiercely she cares. This duality allows the novel to present emotion as a force capable of reshaping lives, communities, and myths.

Rage and love are not opposites here—they are survival strategies, sources of empowerment, and, ultimately, catalysts for change.