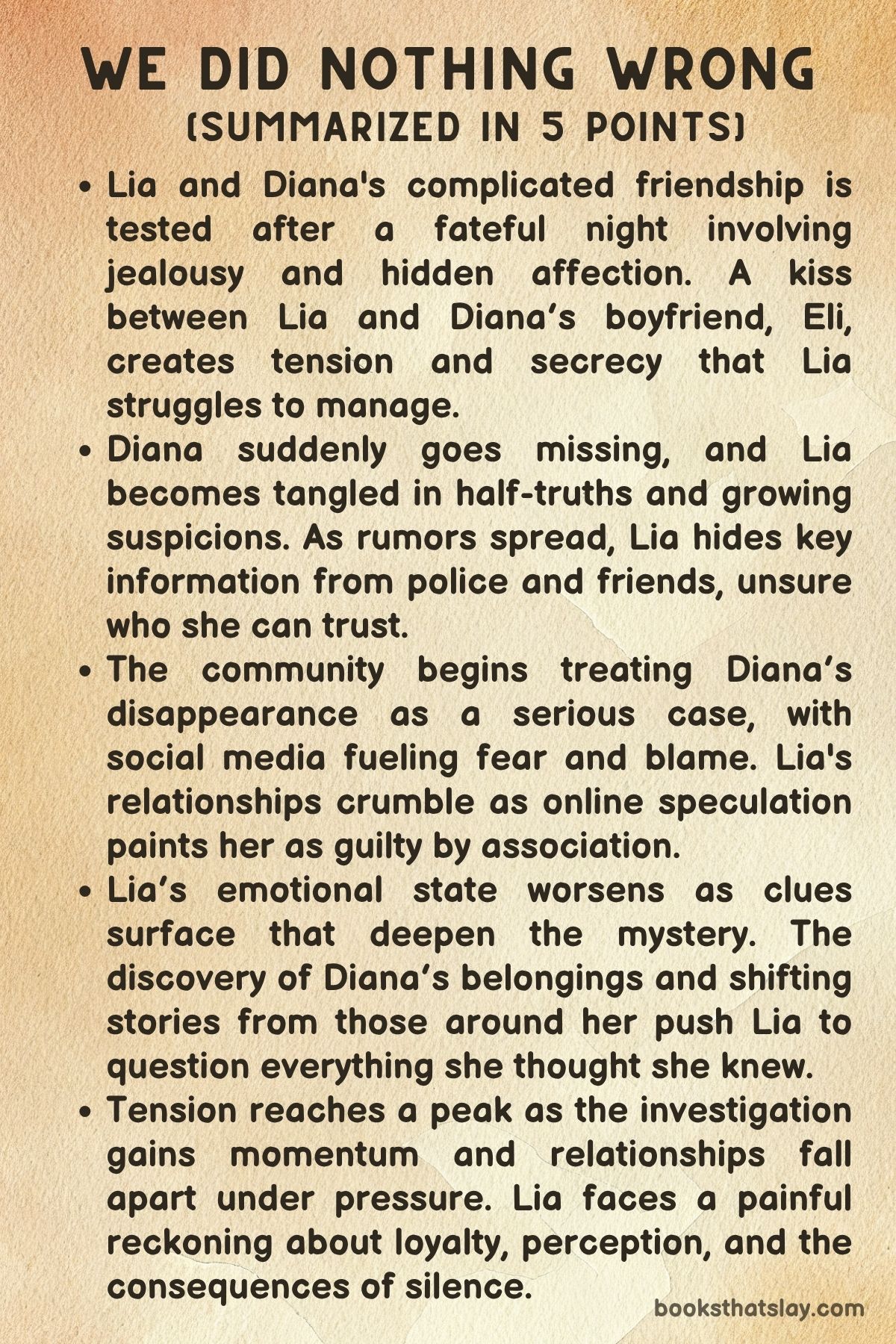

We Did Nothing Wrong Summary, Characters and Themes

We Did Nothing Wrong by Hannah Jayne is a psychological YA thriller that explores the destructive consequences of secrecy, obsession, and fractured friendships. At its center is Delia “Lia,” a teenage girl tangled in a love triangle with her best friend Diana and Diana’s boyfriend Eli.

What begins as a simmering conflict of jealousy and betrayal quickly spirals into something far more sinister. When Diana mysteriously disappears, Lia is left to confront a web of guilt, suspicion, and danger. As her world unravels, Lia must navigate deception, threats, and her own inner turmoil to find the truth before it’s too late.

Summary

Lia, a high school bassist, finds herself swept up in an intense, emotionally fraught situation after a kiss from Eli, her best friend Diana’s boyfriend. This single act triggers a cascade of feelings—desire, shame, and denial—compounded by Lia’s growing resentment of Diana, who thrives in the spotlight and dominates every room she enters.

Their friendship, once intimate and joyful, is now laced with tension and sarcasm. Diana’s recent pageant win only amplifies the cracks in their relationship.

Despite her guilt, Lia convinces herself that Diana is too self-absorbed to truly care about Eli, rationalizing her own escalating flirtation with him.

As Lia navigates this personal turmoil, she begins receiving mysterious roses with chilling notes. Though she initially assumes they’re from Eli, the romantic thrill soon turns into dread.

When she tries to meet Diana to confess her betrayal, she skips the rendezvous in favor of another secret meeting with Eli. The next morning, Diana is missing.

Her bed hasn’t been slept in. Her belongings are untouched.

Panic sets in across the community. Lia’s mind replays the events, her guilt thickening by the minute.

At first, Lia clings to the belief that Diana is orchestrating some grand stunt for attention, something in line with her flair for drama. But the absence stretches too long.

School becomes a minefield of whispers, suspicion, and growing fear. Classmates grow anxious.

Friends begin to question what happened. Lia, overwhelmed by guilt and fear, struggles to keep her own secret hidden.

Eli becomes increasingly manipulative, denying any intimacy while simultaneously begging Lia to lie to the police on his behalf. Then, Lia sees him toss something from his car—an earring that belonged to Diana.

In the face of mounting evidence and Eli’s increasingly erratic behavior, Lia’s grip on reality begins to slip. She questions her instincts, her memories, and even her own innocence.

Meanwhile, Diana’s social media presence—once a source of validation—has become a sinister trail of obsessive comments and invasive messages. It becomes clear that Diana might have been targeted, not by chance, but deliberately.

Even more unsettling, Lia begins to wonder if she was the intended target, and Diana was taken by mistake. The notes, the roses, the silent lurking—each points toward a calculated obsession.

Her suspicions widen. Friends like Rowan exhibit odd behavior, sporting unexplained injuries.

Lia becomes fixated on every offbeat action, unable to distinguish paranoia from intuition. She finds more roses.

One appears in the park where Diana disappeared. Her bedroom is disturbed.

Her yearbook is vandalized—Diana’s face scratched out. Yet, when she brings it to school, classmates accuse her of defacing it herself.

Is someone framing her? Or is she losing control?

Things take a dark turn when Lia sneaks onto Eli’s property and suspects that Diana might be hidden in a locked shed. In a tense confrontation, Eli denies knowing where Diana is but admits to discarding her earring to avoid implication.

He also denies sending the notes. Lia, uncertain whether to believe him, starts fearing for her own safety.

She reports the notes to her parents and the police, only to be brushed off as imagining things or misunderstanding a secret admirer’s attention. This dismissal further isolates her, increasing her desperation.

Soon, Lia is taken. She wakes up bound in the back of a van, confused and drugged.

Her abductor is Tad, a delivery man whose presence had always been in the periphery of her life—barely noticed, always there. Tad is unhinged, claiming that Lia is his one true love.

His obsession is intense and violent, yet he frames it as romantic devotion. Lia learns that Diana had also been abducted by him.

Tad keeps her in a remote house, meticulously decorated with Lia’s pictures and keepsakes, a shrine to a fantasy Lia doesn’t recognize.

In this horror, Lia remembers Diana’s skills in pageantry and performance, and she begins to play along. She feigns affection, tells Tad what he wants to hear.

It’s a strategy to survive. She manipulates his emotions to gain small freedoms, to keep herself alive long enough to find Diana.

Eventually, she convinces him to take her to the attic, where she discovers Diana alive, though battered and barely holding on.

The rescue is delicate. Tad’s instability makes any false move potentially deadly.

He demands proof of Lia’s loyalty, handing her a stun gun and telling her to use it on Diana. Lia takes a risk and stuns Tad instead, giving the girls a narrow window to escape.

The chase that follows is brutal. On the road, Tad attacks Lia, nearly killing her.

But Diana fights back, saving Lia and leading to their eventual rescue when a passing driver calls the police.

In the hospital, Lia is consumed with guilt. She sees herself as responsible—not just for betraying Diana, but for setting everything in motion.

She believes her actions led Tad to Diana. But Diana, though deeply hurt, reassures her.

Their bond, while damaged, remains intact. Through shared trauma, they begin to mend what was broken.

Their mutual apology becomes a moment of redemption.

In the final twist, authorities uncover evidence of another victim—Elise Madrigal. It confirms that Tad had done this before.

He is a serial predator, not a one-time offender. The implication is chilling: Lia and Diana escaped with their lives, but they are not his only victims.

The story closes not just on survival, but on a deep awareness of danger, strength, and the resilience of friendship. We Did Nothing Wrong becomes a haunting reflection on how far people will go to feel seen, loved, and safe—and what it takes to survive being hunted for simply being noticed.

Characters

Lia

Lia, the protagonist of We Did Nothing Wrong, is a complex and emotionally raw character whose internal struggles form the crux of the narrative. At the outset, she is depicted as a talented bassist basking in the glow of a successful performance, but beneath the surface lies a deep well of insecurity and confusion.

Her entanglement with Eli, her best friend Diana’s boyfriend, marks the beginning of her moral unraveling. Lia’s feelings for Eli are a combustible mix of suppressed desire, guilt, and rationalization, which push her to make decisions that fracture her oldest friendship.

Her belief that Diana won’t truly care about Eli reveals her own need to diminish Diana’s feelings to justify her actions. As the mystery of Diana’s disappearance deepens, Lia’s emotional descent accelerates.

The anonymous roses and notes she receives, once tinged with romantic excitement, begin to take on a menacing tone, forcing Lia to confront the possibility that she has been the target of a dangerous obsession.

Lia’s journey is defined by guilt, paranoia, and a desperate need for redemption. The pressure to maintain a façade of normalcy while her world unravels intensifies her psychological deterioration.

She becomes increasingly isolated, especially when her credibility is questioned by her peers and authority figures alike. The final act of her story, which finds her kidnapped by Tad and forced into a horrific charade for survival, showcases Lia’s resilience and ingenuity.

Drawing on her experience as a performer and the survival skills she’s absorbed from Diana, she crafts a deceptive persona to manipulate her captor. Her eventual escape and the trauma she carries mark a profound transformation.

Lia’s story is ultimately about survival in every sense—physical, emotional, and moral. She emerges scarred but not broken, with a deepened understanding of her own strength and the cost of betrayal.

Diana

Diana is initially introduced as the charismatic and dazzling best friend—Miss Popular with a crown and a cult following. However, We Did Nothing Wrong peels back the glossy exterior to reveal a young woman grappling with intense pressures and vulnerabilities.

Though Diana’s confidence and charm often overshadow those around her, particularly Lia, she is not merely a superficial queen bee. Beneath her composed surface lies a girl striving to meet the crushing expectations of pageantry, social media fame, and financial need.

The revelation that she may have been selling images online hints at a desperation hidden from even her closest friends, making her disappearance not just a personal loss but a reflection of broader societal pressures placed on teenage girls.

Diana’s bond with Lia is riddled with tension, love, and betrayal. The two were once indistinguishable—nicknamed “Double Ds”—but have grown apart under the weight of competition and adolescent identity shifts.

Lia’s betrayal by kissing Eli fractures this already fragile relationship, and Diana’s disappearance becomes a haunting metaphor for that broken bond. Even in captivity, Diana proves resilient and strong-willed.

Her survival, despite brutal treatment at the hands of Tad, highlights a quiet strength and sharp intuition. In the final chapters, she plays a crucial role in her and Lia’s escape, confronting Tad and protecting her friend.

Her forgiveness of Lia, once they are safe, is a moment of profound grace, underscoring the depth of their friendship. Diana’s character arc reveals a multidimensional girl—vulnerable yet fierce, wounded yet forgiving—who defies the one-dimensional stereotype she might initially appear to be.

Eli

Eli occupies a morally ambiguous space within We Did Nothing Wrong, acting both as a catalyst and an antagonist in Lia’s journey. Initially perceived as charming and alluring, his unexpected kiss with Lia initiates the story’s spiral of deception and guilt.

Eli’s actions are marked by inconsistency; at times, he seems tender and sincere, while at others he appears manipulative, evasive, and emotionally disengaged. His refusal to acknowledge his flirtations with Lia and his request for an alibi the night Diana disappears create a cloud of suspicion around him.

When Diana’s earring turns up and Lia realizes Eli tossed it out of fear, her suspicions intensify. His romantic gestures, once intoxicating, come to feel invasive and calculating.

Eli embodies the dangers of emotional duplicity and male entitlement. He maintains relationships with both Lia and Diana, managing to sow doubt and guilt in Lia while absolving himself of blame.

His passivity—his refusal to fully commit, confess, or clarify—allows the tension to escalate and leaves Lia increasingly isolated. While he is not the ultimate antagonist of the story, his actions contribute significantly to Lia’s downfall.

By the novel’s end, Eli fades into the background, rendered insignificant in the face of the larger threat that is Tad. His disappearance from the emotional climax reinforces his role as a failed love interest and a symbol of Lia’s misguided choices rather than a true partner.

Eli is a cautionary figure, a representation of how teenage charm can mask emotional carelessness and how inaction can be just as damaging as betrayal.

Tad

Tad is the embodiment of horror in We Did Nothing Wrong—a twisted, delusional man who emerges as the true predator lurking beneath the novel’s surface tensions. A delivery driver with an obsessive fixation on Lia, Tad carefully constructs a fantasy world in which she is his destined partner.

His affection manifests as control, manipulation, and ultimately violence. Tad’s chilling duality—affectionate yet monstrous—creates a claustrophobic atmosphere that drives the novel’s most terrifying scenes.

His home, lined with photos of Lia, becomes a psychological prison where he imposes his distorted reality onto his captives. He justifies his kidnapping and violence through a warped lens of love, convinced he is saving and protecting Lia from a world that doesn’t understand her.

Tad’s interactions with Lia are grotesque parodies of romantic intimacy, where dominance is mistaken for devotion. He oscillates between treating Lia as a cherished lover and a misbehaving possession, demonstrating the depth of his delusions.

His obsession is not spontaneous but deeply planned, suggesting he had stalked and studied Lia for some time, perhaps even mistaking Diana for her in the early stages of his obsession. The revelation of another likely victim, Elise Madrigal, reinforces Tad’s identity as a serial predator rather than an isolated threat.

Despite his calculated cruelty, it is ultimately Lia and Diana who outwit him, using psychological manipulation and performative submission to create a chance for escape. Tad’s downfall is as dramatic as his reign of terror—taken down not by brute force, but by the very girls he sought to dominate.

His character serves as a grim reflection of how obsession, entitlement, and violence can intertwine under the guise of affection.

Rowan

Rowan is a minor but thematically significant character in We Did Nothing Wrong, serving as a barometer for the shifting social climate around Lia. Though his role is peripheral compared to the central quartet, Rowan’s presence offers a lens through which readers can observe Lia’s transformation and the unraveling of her relationships.

He is initially portrayed as sarcastic and teasing, but his remarks carry undercurrents of suspicion and judgment. When Diana goes missing, Rowan becomes one of the voices that casts doubt on Lia’s narrative, reflecting the broader social alienation she experiences.

His accusations—particularly when Lia presents the defaced yearbook—underline how quickly peers can turn from bystanders to critics, especially when fear and rumor take root.

Rowan also acts as a reminder of the performative nature of high school relationships and social dynamics. He’s aware of Diana’s flair for drama, but his perspective adds a layer of uncertainty: is he an astute observer or just another teenager swept up in the chaos?

His role is not heroic, nor is it malicious; he represents the ambivalence of the outside world. In a story dominated by emotionally charged relationships, Rowan’s presence offers a contrast—a character who observes more than he acts, and who serves as a mirror to Lia’s deteriorating image in the eyes of her peers.

While not central to the plot, Rowan is integral in showcasing how rapidly public perception can shift and how deeply it can wound those already on the edge.

Themes

Obsession and Control

In We Did Nothing Wrong, obsession surfaces as a terrifying force that distorts perception and warps the boundaries of consent, identity, and reality. Tad’s fixation on Lia is not borne from any genuine understanding of her but from an illusion he has built through voyeurism, fantasy, and unchecked desire.

His collection of photographs, his mimicry of affection, and his justification for kidnapping and murder reflect a need not only to possess but to control. Lia becomes a symbol of his imagined perfect partner, and when reality fails to align with his fantasy, he resorts to violence to force the narrative into place.

This obsessive behavior is mirrored on a smaller scale in Lia’s own romantic confusion, particularly in her justifications for her feelings toward Eli. Her desire to be seen, to feel significant in the shadow of Diana, primes her to mistake attention for affection and encourages her to ignore warning signs.

The novel thereby creates a terrifying continuum—from adolescent longing to predatory obsession—highlighting how unchecked entitlement and objectification can escalate into horrific consequences. Tad’s obsessive tendencies are chilling not just because of what he does, but because of how ordinary he appears until his mask slips.

His obsessive love masquerades as devotion, but it is ultimately rooted in control and annihilation of the subject’s autonomy. Even Lia’s initial feelings of flattery at the anonymous roses and notes slowly curdle into fear, suggesting how easily romantic gestures can mutate when born from obsession rather than genuine connection.

Guilt and Responsibility

The emotional backbone of the story rests in Lia’s deepening sense of guilt and responsibility, which compounds with every choice she makes. From the moment she kisses Eli, Lia begins a chain of self-deception, silence, and delayed confessions that slowly fractures her sense of self.

What might have been a teenage mistake is compounded by her reluctance to admit wrongdoing, particularly to Diana, whose brash exterior masks profound vulnerability. Lia’s guilt begins with a private betrayal, but when Diana disappears, that guilt metastasizes into a belief that her desires and actions may have led to tragedy.

This theme becomes even more visceral after Lia is kidnapped. She begins to see herself as not only responsible for Diana’s vanishing but also complicit in the broader narrative of violence and misrecognition.

Her internal monologue is steeped in regret—what she didn’t say, what she should have done differently—and she grapples with the haunting possibility that Diana was taken in her place. Guilt, then, is not just emotional weight; it becomes a lens through which Lia reinterprets all her past behavior.

This burden culminates in the hospital scene, where she seeks forgiveness from Diana, not only for kissing Eli but for allowing jealousy, selfishness, and silence to widen the gulf between them. The novel suggests that guilt cannot be erased by simple apologies; it must be reckoned with through action, accountability, and truth.

Female Friendship and Rivalry

The bond between Lia and Diana is as volatile as it is formative. Their friendship, rooted in shared childhood and adolescent intimacy, is shaped by a complex mixture of admiration, competition, loyalty, and resentment.

Diana’s pageant success and social dominance cast a long shadow over Lia, who feels increasingly diminished and overlooked. Yet, beneath their biting sarcasm and social posturing lies a deep emotional tether—one that neither truly understands until it is nearly severed.

What begins as subtle rivalry morphs into betrayal, but the novel refuses to simplify either character. Diana is not just the attention-seeking queen bee; she is also a girl under immense pressure, navigating financial strain, unwanted attention, and the fragile currency of online fame.

Lia’s betrayal is not merely a product of envy, but also of a longing to be chosen, to matter in a way she feels Diana always has. Their dynamic is emblematic of how female friendships in adolescence can be both nurturing and toxic, intimate and destructive.

But the story also showcases reconciliation and renewal. In their harrowing shared captivity, the girls are stripped of artifice.

What remains is raw trust and the instinct to protect one another. In the hospital, their ability to forgive each other marks a turning point, underscoring how even fractured friendships can serve as lifelines.

The story honors the intensity of female friendship in all its messiness, showing it as a force capable of both devastation and salvation.

Performance and Survival

Throughout We Did Nothing Wrong, performance operates on multiple levels—as a literal motif linked to music and stage presence, and as a metaphor for emotional camouflage and survival. Diana’s life is built on performance: the smiling pageant girl, the social media persona, the curated image of perfection.

Lia, though more introverted, performs too—in the band, in her silence around Eli, and later, in her calculated manipulation of Tad. The book draws a compelling parallel between the performative demands placed on teenage girls in public and the performances they must enact in private to protect themselves.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Lia’s captivity. Drawing from Diana’s coaching and her own instincts, Lia adopts a persona to survive.

She says what Tad wants to hear, mimics affection, and crafts an illusion of submission to manipulate her captor. The line between acting and being becomes dangerously blurred, but in this theater of survival, performance becomes power.

The narrative subtly critiques how girls are often taught to prioritize likeability and self-presentation, even in situations of danger. It also highlights how the performance of femininity—be it through pageants, flirting, or emotional restraint—can serve both as a shield and a trap.

The story doesn’t condemn performance outright; instead, it interrogates its necessity and cost. Ultimately, Lia and Diana’s final acts are not scripted for applause but born from instinct and will.

In surviving, they reclaim authorship of their stories, no longer performing for others, but asserting their truth.

Misidentification and Erasure

The concept of being mistaken for someone else recurs with increasing menace throughout the story, elevating what might seem a minor theme into one of existential terror. Lia and Diana, once dubbed the “Double Ds,” are frequently confused for each other—a casual misrecognition that turns deadly when Lia suspects the wrong girl may have been targeted.

This confusion reflects a broader societal tendency to erase individuality, especially among young women who are often judged by appearance, popularity, and conformity. The anonymous roses and notes, initially thrilling to Lia, suggest an admirer who sees only a projection, not a person.

Tad’s fixation on Lia reveals this in its most horrifying form: he doesn’t love her, he loves an idea he has constructed from afar. Diana, too, becomes a victim of this erasure.

Her online persona, shaped by filters and likes, hides a girl in pain, struggling for control. The novel suggests that the danger of being misidentified isn’t just physical—it’s psychological.

When your identity is misunderstood or appropriated, your voice loses power. Lia’s yearbook being vandalized, her classmates’ growing suspicion, and the adults’ failure to believe her all echo this theme: her truth is easily overwritten.

Even when she tries to sound the alarm, she’s dismissed. The story asks what it means to be seen and heard on one’s own terms and how easily that visibility can be distorted, denied, or stolen.

It’s not just about being mistaken—it’s about the terrifying consequences of being unseen in a world that insists it knows who you are.